Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy: Volume 1

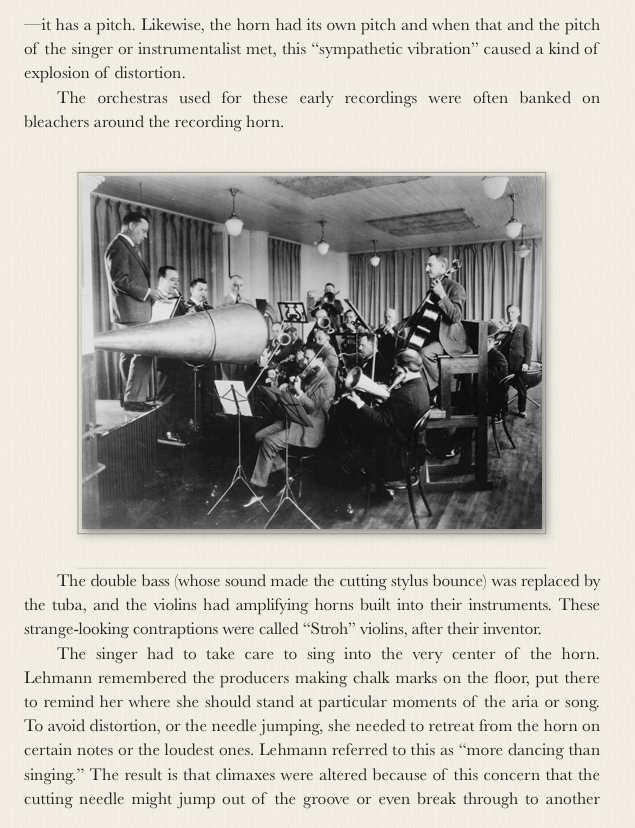

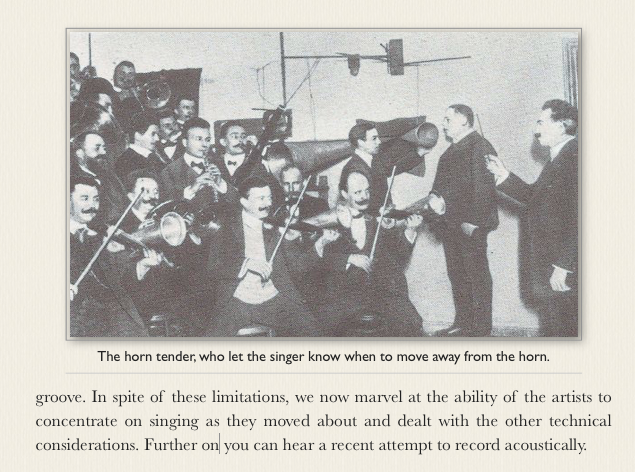

This excerpt from a 1946 MGM movie includes a fairly accurate depiction of the method used in an acoustic recording. Notice the tender, who moves Lauritz Melchior away from the horn to avoid distortion. Also, the violinists have horns on their instruments to amplify their sound.

By February of 1927 Odeon was exclusively using the microphone and the resulting sound had vastly improved.

Finally the words, with all the enunciation for which Lehmann was famous, were able to be heard. Sadly, all the defects of the accompanying orchestras were also apparent! It is hard to believe that members of the Berlin State Opera Orchestra played so out of tune! Of course it wasn’t the whole ensemble, the conductors weren’t always first rate, there was no rehearsal time allowed, and the acoustics of the recording studios were primitive. But the poor intonation of the strings makes for distracting listening to many of these recordings and especially to an otherwise admirable recording that Lehmann made of Schubert’s “An die Musik” in 1927.

This is only one example in which the accompaniment is bothersome to the listener now many years removed from the original recording. The obvious indifference to intonation included the piano which often was un-tuned. It has been suggested that improper playback speeds and other technical matters might account for some of these intonation problems. If this were the case, why does Lehmann always sound in tune?

Earlier I mentioned that art songs were orchestrated for early recordings—record companies assumed that their listening (buying) public might feel cheated with just the original piano accompaniment. Thus, the café orchestra, the salon orchestra, or the instrumental trio often accompanied Lehmann’s early Lieder recordings. The in-house arrangers took liberties to “improve” on the harmonies of such masters as Schubert and Schumann. Added inner lines and extended introductions were often part of the process. Unintended intonation problems of the orchestra exacerbated things.

One of the limitations of recording after 1927 was the use of just one microphone. Whether recording a singer with a Wagnerian orchestra or a piano, the microphone was placed near the singer, with the result that the accompaniment was never at the dynamic level we expect in a concert hall or opera house.

The same limitations of about four minutes per side still continued for electric recordings. In 1930 Lehmann made her first “Erlkönig” recording. There is a clear scramble to fit it on a 10-inch side when a 12-inch disc was really needed. The pianist couldn’t manage the triplets, Lehmann is rushed and the result is disappointing. Later recordings corrected this.

During the electric recording era, there was still both frequency and amplitude loss, though not to the same extent as with acoustic recordings. When Lehmann (or others) sang a loud climax, the engineers turned down the volume to avoid distorting. They sometimes overdid this, short-changing us some wonderful moments, but they were doing the best they could within the technology available at the time.

When I interviewed Lehmann by telephone in her 85th year, I asked about the rehearsal for a recording of the now-classic Die Walküre with Bruno Walter conducting. Was there a lot of preparation, rehearsal and such? “Ach no, Gary. We knew it already!” was the response. And this was not unusual. For some reason there was a very casual attitude towards recording. It was seen as a “commercial” rather than an “artistic” endeavor. Lehmann herself recalls joking with her close friend Elisabeth Schumann, that they’d made some recordings this month “for a little extra mad money.”

Sometimes when the 78s were transferred to LPs, it was thought necessary to “improve” the sound with an echo chamber (resonance) effect. Also the effort to eliminate the hiss of the surface noise could wipe out the high harmonics of the voice. With CDs the problem of surface noise is often well handled, but there are those who hear a great loss in the harmonics and overtones that give a voice character.

Nearly all the operatic music Lehmann recorded is in German, no matter the original language. It was the custom of the time for opera to be sung in the language of the country in which it was performed. Hence this ecstatic 1932 recording of Butterfly’s entrance is in German–and nothing seems to be lacking.

In opera performances, the preceding Lehmann example was not an anomaly. Lehmann (and other famous soloists) sang French roles in German even in Paris! To be fair, the French singers sang the German roles in French. So we have the almost comical confluence of a great singer such as Lehmann, performing a Wagnerian opera in Paris, in which she was the only one singing the original language.

Lehmann’s Recording of Rosenlieder

Correspondence from Horst Wahl:

To my great joy I have discovered that some of my earliest professional recordings, produced more than 64 years ago for the Odeon recording firm, have just been resurrected on a compact disk. Lotte Lehmann’s interpretation of the Rosenlieder of Count Philipp zu Eulenburg [and Werner’s song] are on Pearl GEMM CD 9409.

Eulenburg (1847-1921) belonged to Kaiser Wilhelm II’s closest circle of friends and was elevated to the rank of prince in 1900. His hobby was the composition of songs in the folk tradition, and his Rosenlieder cycle enjoyed great popularity in the period just before the first World War. As it did not present great difficulties in its vocal, piano or violin parts, it was often quite satisfactorily performed during evening soirées by music-loving amateurs.

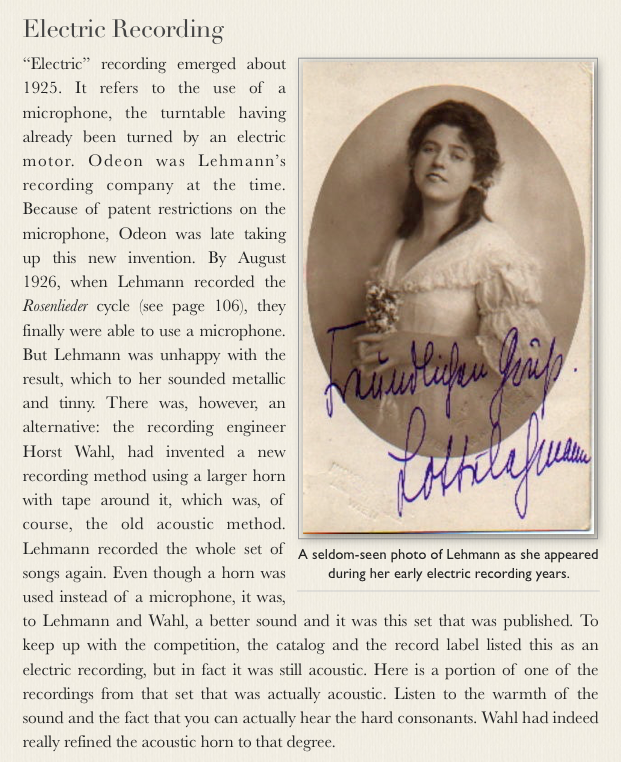

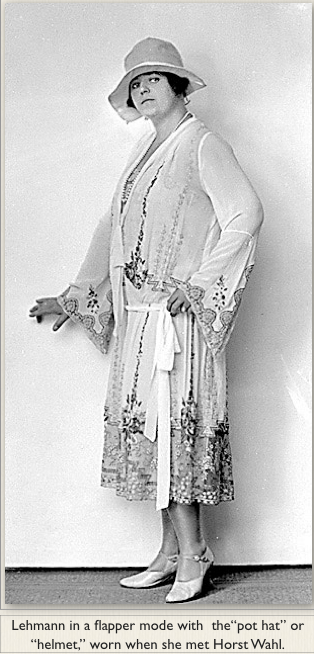

At the time the Rosenlieder recordings were made, on 5 August 1926, I was still quite a young man and had been employed a year and a half on the retail sales staff of Odeon. My acquaintance with Lotte Lehmann began in May of 1925 when the artist entered our retail outlet on Leipziger Street in Berlin one day to listen to a few new recordings of prominent sopranos. Although I was, of course, quite familiar with her appearance in photographs and on the Berlin Opera House stage, I did not immediately recognize her as she was wearing the latest rage in women’s hats of the period. It was rather a pot-like affair and covered her face down to the eyes. When she asked me which sopranos I would especially recommend, I replied with cool placidity and the deepest certainty, “Well, if you ask my opinion, madam, there is only one—Lotte Lehmann. She is the greatest of them all.”

You can well imagine how such a young coxcomb as I might have felt when from under the stylish helmet came the vigorous reply, “Thank you, young man, that is who I am.”

There have been few times in my life as perplexed and confused as those moments. I might as well have been struck by lightning. From this moment on began a deep friendship [and more…] which lasted for ten years and which belongs to the most wonderful experiences of my long life.

I had at that time a sound studio in Berlin on Augsburger St., where for three years I had produced for the private use of my customers, acoustic recordings on zinc, acetate or other synthetic materials. Among my clients were such important singers as Joseph Schwarz, my neighbor; Meta Seinemeyer, Sabine Meyen, Hedwig Francillo-Kauffmann, Margarethe Matzenauer, Michael Bohnen, and Alexander Kirchner.

When I mentioned this sideline occupation to Lotte one day, she immediately decided to test her voice on my equipment. Among the test recordings were duets which we sang together, (I had studied voice with Prof. Bernhard Ulrich), among them the Rosenlieder of which we were both especially fond.

As we listened to these recordings, the sound of her voice and also of the accompanying piano was so remarkably natural sounding by acoustic recording standards of the day, that she asked me if this lieder cycle might not be commercially produced by Odeon.

At that very time, a major technological change was rolling through all recording firms: electric recording. Odeon had already taken its first steps in this direction, and it appeared as if the Rosenlieder with its simple piano and violin accompaniment would be an ideal test.

During the first electric recording session with Lehmann on 2 August 1926, I was otherwise employed and not at hand. Three days later we (Lotte, Dajos Bela, Mischa Spoliansky, Georg von Wysocki, Odeon artistic director, and myself) listened to the sample recordings.

It was sadly obvious to all of us that the electric microphone had not done justice to either Lotte’s wonderful voice or Dajos Bela’s lovely violin. Both came over the loudspeaker with much too sharp a sound.

After a conference with the management of the firm, Lotte was able to get permission for me to record these songs acoustically, using my own methods. To this end I then brought to the Odeon studio my own large horns, one for the singer and one for both accompanists.

Whereas the Odeon “Trichter” [horns] were made of cloth, the horns I had made for myself were of metal wound with insulating tape to prevent self-vibration. The larger diameter of these horns allowed the singer to come so near the device that occasionally her head would project into it. Happily for me, the calm and not overly tempestuous nature of the music worked all to the good, and most of the danger of “blasting” was avoided.

Lotte Lehmann signed the release for publication of the Rosenlieder on 14 December 1926. This lieder cycle was first offered to the public in March of 1927 under the errant nomenclature “Electric Odeon Recording,” and in succeeding years, due to its high quality, it continued to be listed in all the catalogs as “electrically recorded.”

Mischa Spoliansky, like Lotte Lehmann, lived a long life, and even in his late 80s appeared on German television recounting incidents of his artistic life.

In these songs Lotte quite consciously used a short and frequent taking of breath as a medium for musical expression, evoking her passionate presence. Instead of the higher range usually found in her other recordings, her voice moved here within a quite enchanting mezzo range.

If I allow a little self-praise here, the reproduction of the original Rosenlieder belongs to the best of acoustic recordings and is nearly impossible to distinguish from early electrics. Voice and accompaniment are both well balanced. The clearly audible breath brings the singer to vivid life before us. The current reissue on compact disk presents the first publication of the Rosenlieder since they were issued on 78rpm shellacs.

(From personal correspondence between the author and Horst Wahl.)

You may wish to hear one of the acoustically recorded Rosenlieder again.

———————————————————————————————

Note: The following pages offer a modern perspective on early recordings.

In April 2018 the following experiment took place:

Susanna Phillips, a star soprano at the Metropolitan Opera, was listening to a recording of herself one recent afternoon, as she had done so many times before. This time, though, something wasn’t quite right.

“I can’t tell it’s me,” she said. Her rich tone sounded thin; her usually steady vibrato was strangely shaky.

The difference was the way her voice had been captured: that is, the same way they used to do it more than a century ago. It was a method that offered a pale — if, back then, magical — approximation of opera’s greats.

Whenever Luciano Pavarotti was asked to name the greatest tenor ever, he always answered Enrico Caruso, who became a household name from his recordings, made from 1902 until his death in 1921.

But how did Pavarotti know? Especially on Caruso’s breakthrough records, the sound is scratchy, wiry and wobbly. The same holds true for early recordings of Nellie Melba, Luisa Tetrazzini and other luminaries of that era. While there are entrancing hints of astonishing voices, it’s hard to tell what they were really like. If only we could record a singer today on the equipment used back then and compare the playbacks to modern recordings.

Well, that precise experiment took place earlier at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, thanks to the curiosity of Piotr Beczala, a leading Met tenor.

Touring the Met’s archives a couple of years ago, Mr. Beczala mentioned that his dream was to record some arias under early-20th-century conditions. He wanted to learn firsthand how faithful — or far-off — the results would be.

Peter Clark, the company’s archivist, mentioned Mr. Beczala’s fantasy to Jonathan Hiam, the curator of the performing arts library’s Rodgers and Hammerstein Archives of Recorded Sound; Mr. Hiam then contacted Jerry Fabris, from the Thomas Edison National Historical Park in New Jersey, who knows a collector in Illinois who makes wax cylinders like those Edison once produced.

So on his day off from the Met’s revival of Verdi’s Luisa Miller, Mr. Beczala got together with Ms. Phillips and the technical team to try out the vintage operation.

The library owns Edison cylinder machines, as well as an early Berliner gramophone—a competing technology that used flat discs. In 1912, Mr. Fabris explained, flat-disc phonographs finally outsold the cylinder ones and before long took over the market.

Mr. Fabris had brought similar equipment from New Jersey: an Edison Home Phonograph with a large black bell horn, a rotating holder for the wax cylinders and a hand-crank device to wind up the internal springs; and a similar-looking Edison Fireside Phonograph to play back the recordings. Both machines date from around 1909.

The material surrounding the wax cylinders is not really wax, he said, but something called metallic soap. Before using the cylinders, he had to warm them up under a light to make the material soft enough for the stylus to cut grooves as the disc spun.

“You want it to be like butter,” Mr. Fabris explained.

The process is better at recording midrange sounds and has trouble with high frequencies. (Ms. Phillips was warned that it tends to favor tenors over sopranos.) Wide dynamic variables also test the machine’s capacity: Not knowing this, Ms. Phillips had prepared “Per pietà,” an aria from Mozart’s Così Fan Tutte that moves through extremes of high and low, loud and soft.

But Mr. Beczala was first up, singing “Quando le sere al placido” from Luisa Miller, accompanied by Gerald Moore, who played on a small upright piano so as not to compete with the voices. Putting the cylinder in place, Mr. Fabris was careful not to touch the surface: Even a slight thumbprint can create an impression. While Mr. Beczala sang, Mr. Fabris held a small brush in one hand and a little squeezable air bag in the other to disperse the dust-like shards of wax that are created when the stylus cuts into the cylinders.

Since the machine has no meter to check levels, Mr. Beczala tried out the opening of the aria twice, the second time moving closer to the machine. Both times, the ringing, virile quality of his sound came through fairly well, though dynamic variations essentially disappeared. Mr. Beczala was most rattled that his intonation sounded off—though this was a flaw of the equipment, not of his solid technique.

Finally, it was time to record the aria—or at least the first half or so, since each cylinder can hold only a little more than two minutes of music. “It’s like a black hole,” Mr. Beczala said, staring at the bell horn. “It takes you in.”

Listening to the playback, he commented that the resonance was not bad and that the high notes were O.K. But his softer singing sounded faint and distant, and the consonants, he said, “are non-existing,” though in the room his diction was excellent.

“The Flower Song,” from Bizet’s Carmen, came through more clearly. “I tried to sing more crisp than usual,” Mr. Beczala said.

When Ms. Phillips tried out the faster section of “Per pietà,” full of florid runs and roulades, she proved a quick study at the skill of leaning forward for soft passages and way back for louder ones, standard practice during Caruso’s era.

“You have to romance the horn,” she said.

To end the session, the two singers tried out some of the Act I love duet from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. The machine is “not forgiving,” Ms. Phillips said, adding: “The tone quality changes, but not the dynamic. That’s infuriating to me.”

The contrast between their big, healthy voices and the crackly, thin recorded playbacks was stark. It proved just how difficult—indeed, impossible—it was to capture the sounds of the legendary singers a century ago.

Yet context is everything. For opera lovers in the 1910s, it must have seemed simply miraculous that the great voices could appear at will, however flawed their sound, in your living room. Here’s a YouTube video of the event.

—————————————————————————————————————–

Special Lehmann-related material on recordings:

Lehmann Interview on Recordings

Odeon Records catalog pages that include Lehmann (1924-1934)