Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy: Volume 1

Legendary: The most feared and revered conductor of the 20th century, Arturo Toscanini, called Lotte Lehmann “the greatest artist in the world.” One of the early 20th century’s really successful composers, Richard Strauss, uttered the words that are now engraved on her tombstone: Sie hat gesungen, dass es Sterne rührte—her singing moved the stars. Giacomo Puccini, the opera composer of her time, preferred her “soavissima” Suor Angelica to all others.

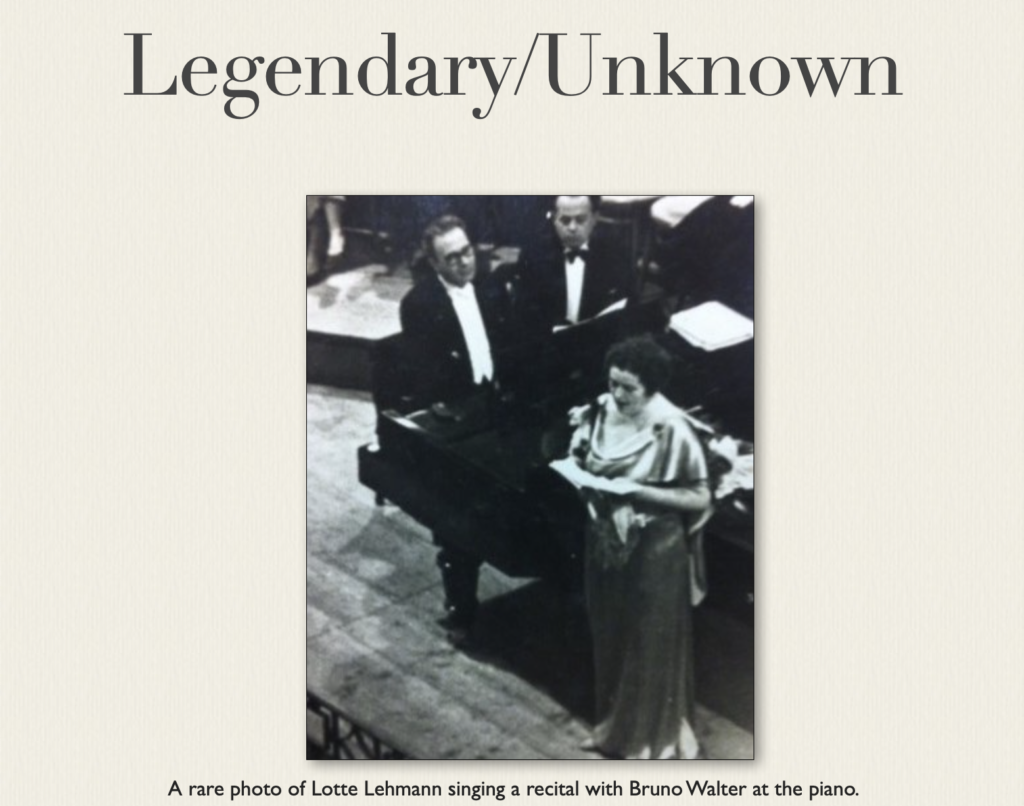

Unknown: Nowadays most people have no idea who Lotte Lehmann was.

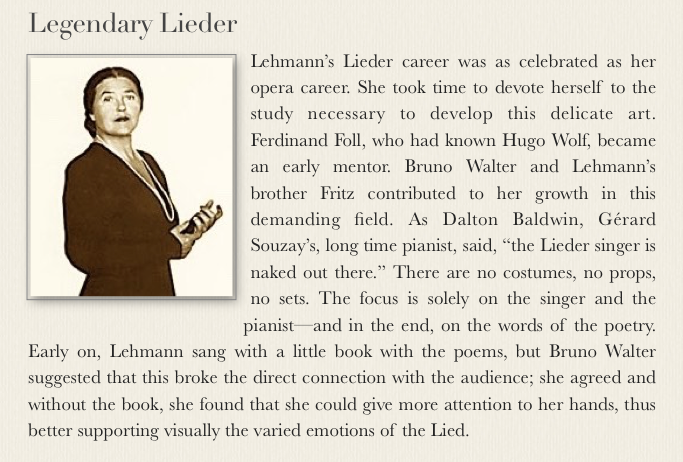

This presentation examines the legacy of Lotte Lehmann, who, during her opera career’s zenith from the 1920s to the 1940s, was considered the most significant singing actress to be heard on stage or on recordings. Her Lieder career overlapped her opera life and continued until 1951. Finally, Lehmann taught, with more claim to success on that account than any other celebrated singer. The chapter called The Third Career covers Lehmann the teacher; this one is devoted to her singing, both opera and Lieder, with recorded examples.

Fortunately for those interested in Lehmann’s singing art, she made many recordings. Although some of the recording techniques available at the time were primitive, her ability to project what she was singing—expressively and emotionally, even in a recording studio—can make a listener feel the music almost viscerally.

Even so, many fans insisted that what we can hear from recordings are dull, lifeless representations, as compared to experiencing Lehmann’s live performances.

Those of us who never experienced her on stage are nonetheless thrilled with what we hear in recordings. She projected the poetry or libretto with complete authority and emotional involvement. But the way she moved, her facial expressions, and her hands were all said to have been as expressive as her singing. Here is a video from a master class that demonstrates some of this talent.

And that brings us to an examination of her voice. In her prime it could be so sweet, so beautiful, so gracious, that we almost forget to pay attention to the words. Just listen to Lehmann’s creamy sound of this 1928 recording of “Mit deinen blauen Augen” (With your Blue Eyes) by Richard Strauss. Though we may become enchanted by the opulent sound, we can also understand every word and their nuances. The “118” relates to the number found in the Discography in the Appendix.

Sometimes we do need to understand the words or situation to revel in her fervor, her complete identification with the moment or the character’s feeling. Lehmann’s emotional voice in this 1935 recording can sound almost silly if we don’t know that Sieglinde has been separated from Siegmund and is desperate to warn him in this scene from Wagner’s Die Walküre.

Translation: Listen, oh listen! That’s Hunding’s horn. His gangs are coming fully armed. No sword will serve when their dogs attack. Throw it away, Siegmund. Siegmund, where are you? Ah, there—I see you—Horrible sight! The dogs are gnashing their teeth at your flesh; they don’t respect your noble features; they fasten their firm teeth on your leg, you fall, your sword shatters in pieces. The tree topples, the trunk breaks. Brother, my brother, Siegmund—Ah!

Partly because one of her teachers forced her to sing over and over the legato aria “Dove sono” from Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, and in some measure because she heard how singers of the latter half of the twentieth century consciously used “performance practice,” she wasn’t pleased with her Mozart recordings. I had planned to play some of her Mozart arias for her 85th birthday tribute on WBAI, until Lehmann stopped me. In My Many Lives, Lehmann wrote about never finding her way to Mozart’s “ethereal language of the heart,” suggesting that she may have “always been too earthbound in my feeling.” “I feel that in singing Mozart, emotion should be expressed just as warmly and glowingly as in other operas. It only wears a more supple cloak.…” One can compare this 1927 recording Lehmann made of “Heil’ge Quelle” with an excerpt from a 2008 performance of Véronique Gens in the same aria originally called “Porgi Amor.”

You’ll hear that there’s no shame in Lehmann’s singing of the aria. The legato line is never interrupted, even in the German translation that she sings. She’s able to convey her feelings about her straying husband and, without sentimentality, her longing for his return. This is a human woman, not the Countess, in distress and pouring out her love.

Here’s the general sense of the words: Oh, Love, give me some remedy; For my sorrow, for my sighs! Either give me back my husband, Or at least let me die.

As she aged, her voice lost some of its sheen, luster, and ease. In the Lieder recordings and radio broadcasts made from 1935 through 1951 we can still hear the way Lehmann could color a word, or add allure or charm to a phrase by her piquant changes in tempo or the suggestive use of portamento to add a sly or impish touch. Listen to this in this Mozart song of young impetuous love called “Die Verschweigung” (Concealment) from 1935. The pianist is Ernö Balogh.

You can find the list of Lotte Lehmann’s Opera Roles in the Appendix. It is impressive for both the number and the variety. She sang many small roles at the beginning of her career and gradually portrayed the greatest lyric soprano opera roles of the repertoire.

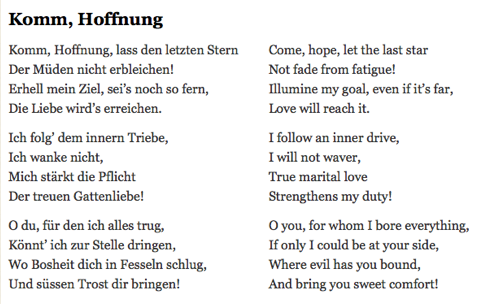

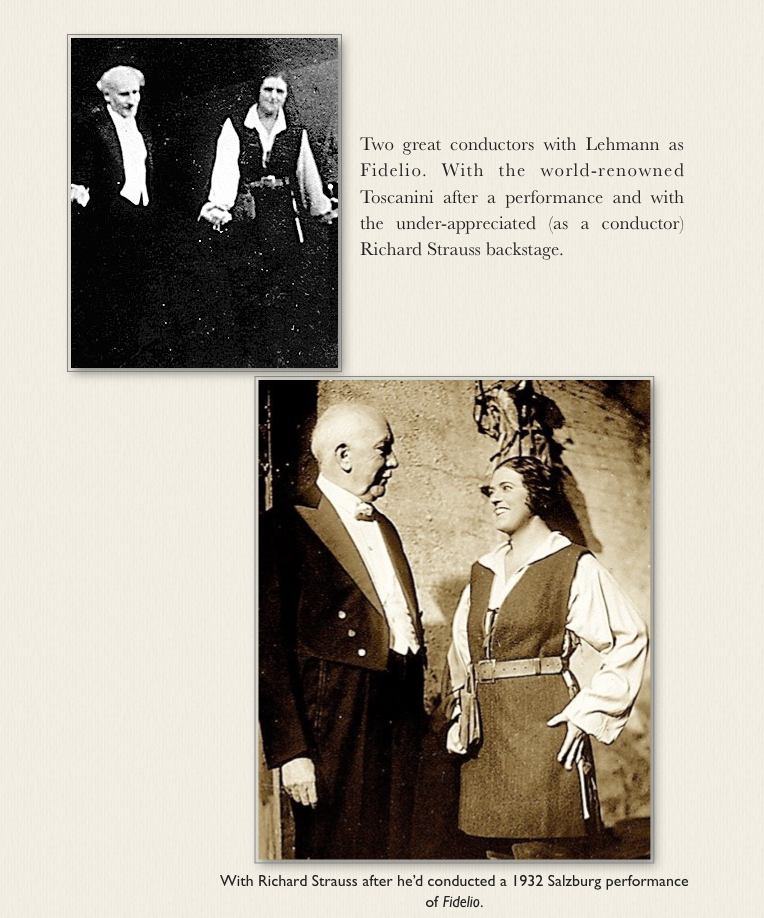

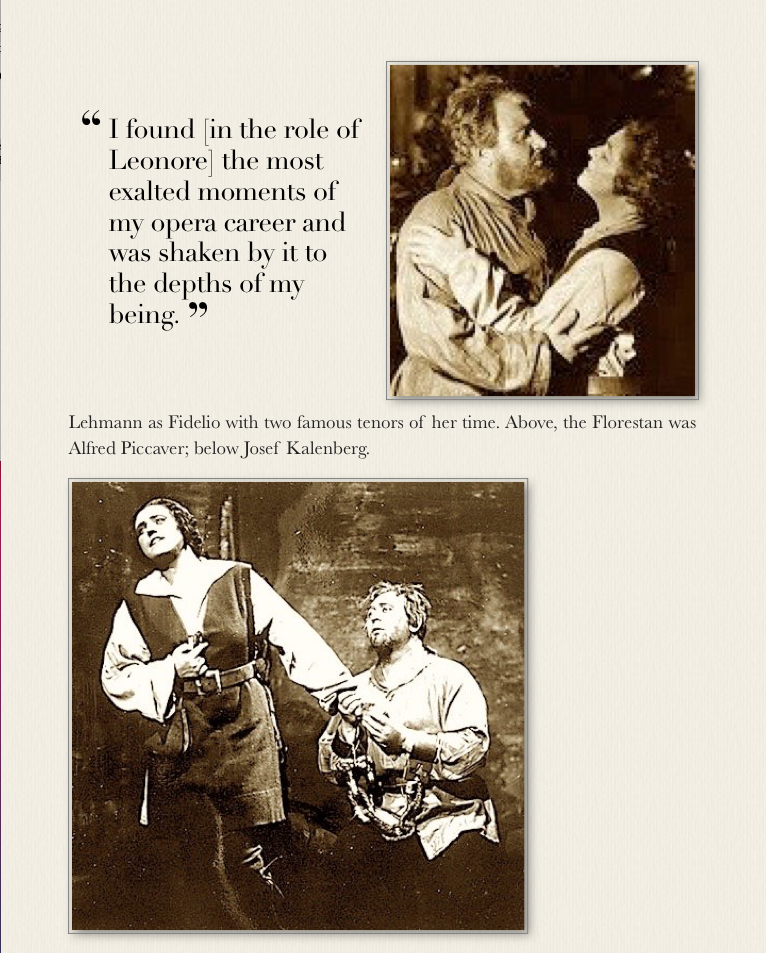

Despite learning and performing more than 90 roles, the fabled aspect of Lehmann’s opera career is no doubt based on her performances of a few that she made her own and that became identified with her: Beethoven’s Fidelio; her Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier of Richard Strauss; and the Wagner roles of Elsa in Lohengrin, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, and above all, Sieglinde in Die Walküre.

In Hamburg on the night of 29 November 1912, after only two years with the company, Lehmann made her debut as Elsa, a demanding leading role that demonstrated her acting and emotive singing ability. Her success so established her position at the Hamburg Opera that thereafter she was regularly offered major roles. The critic of the Neue Hamburger Zeitung wrote: “The swan knights we have known here have seldom rushed to rescue a more enchanting, more tender Elsa, so touched with romantic magic, as she was outwardly portrayed by Frl. Lehmann. An Elsa without the excesses of the usual prima donna, an Elsa who was all innocence and guilelessness. Artistically too, Frl. Lehmann fulfills her task for the present in a way that is entirely her own.[…]”

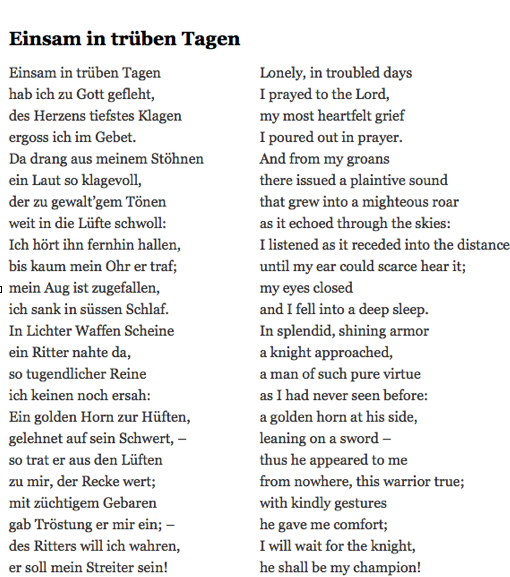

Though Lehmann herself did call Elsa something of a “silly goose”* you wouldn’t know it from the bold commitment we hear when she sings of her complete faith that a knight in shining armor will soon appear to be her champion. *because Elsa asks Lohengrin the forbidden question.

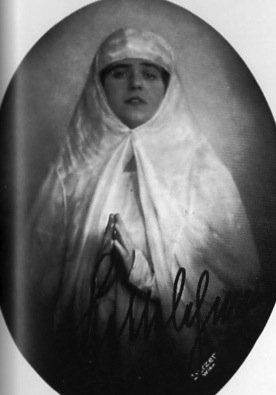

In these rare early photos of Lehmann as Elsa one can observe the devotion and concentration that one also hears in every Lohengrin recording she made. Lehmann wrote in her book My Many Lives that “…Elsa is represented as so lost in her dream that she seems to lose any personality which she might have, in a sickly sweetness.” Obviously, this is not how Lehmann interpreted the role.

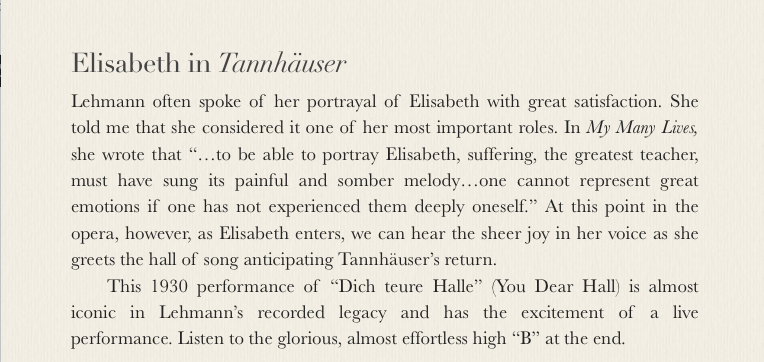

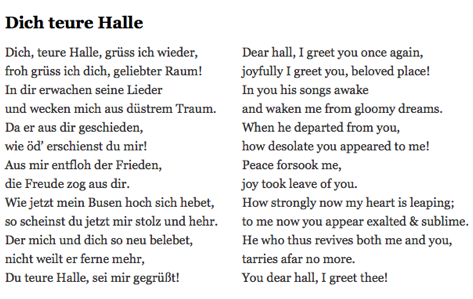

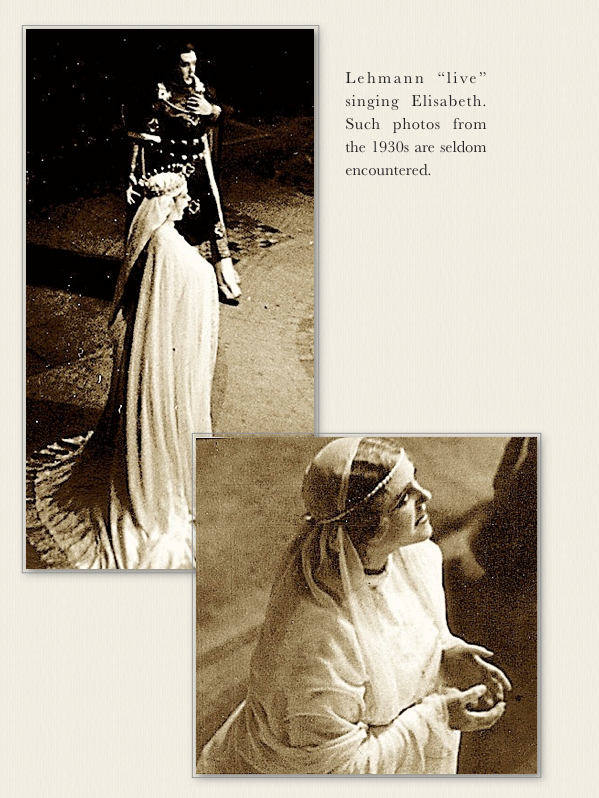

In 1924 a Dresden critic wrote of Lehmann’s Elisabeth: “The voice has the intoxication of youth, bubbling over with the blissful joy of singing. Then there is the great temperament, not just in the acting but also in the voice. Further, there are the fabulous high notes which soar so victoriously over the ensemble, dominating it effortlessly. It was already a magnificent achievement purely from the vocal point of view; it became even more so through the acting. The appearance alone was enough to win us over. One could believe her to be one of those lovely sculptured figures from the Naumburg Cathedral. But that was the external surface. High above that was what Lotte Lehmann accomplished with her portrayal….Here was embodied humanity….”

“Du bist der Lenz” (You are Spring) is one of the few arias in Die Walküre and as such many sopranos sing it on recital and concert programs. The story is too long and complicated to give even a general idea, but you can follow the words that tell you enough for this aria’s meaning.

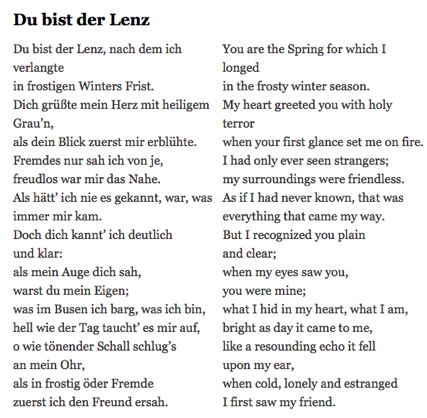

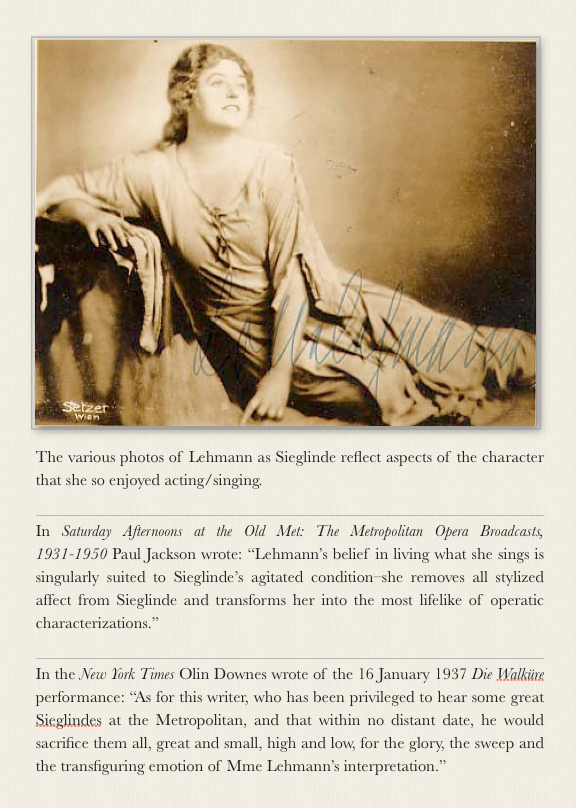

In My Many Lives, Lehmann tells us that Sieglinde is the surely “…the nearest to our feeling…she is close to the earth and humanly convincing.” Sieglinde gradually recognizes in Siegmund all that her life lacks.

In the Foreword to Lehmann’s Eighteen Song Cycles famed critic Neville Cardus wrote of Lehmann’s Sieglinde as follows: “As she came on the darkened stage at the beginning of Act I of Die Walküre, and saw the exhausted Siegmund lying prone, and whispered: ‘Ein fremder Mann’, we could almost hear the heart of Sieglinde beating. She leaned forward, the whole woman of her expressing curiosity, apprehension and—also—an intuitive, prophetic sympathy, an unaware sister-love. I recall with vivid return of reality her marvelous moment when Sieglinde says: ‘Hush! Let me listen to thy voice. I heard it as a child’—(‘O, still! Lass mich der Stimme lauschen; mich dünkt, ihren Klang hört’ ich als Kind’). The voice of Lehmann passed almost into silence as she sang ‘hört’ ich als Kind’; we could feel her mind going back in time and listening within itself for long-forgotten tendernesses. Then Lehmann gave a quick gasp of ecstasy, and her ‘doch nein!’ caught at our heartstrings.”

Sieglinde: Do not plague yourself with worry about me. Death is all I want. Who asked you, maiden, to carry me from the fight? In the flurry there I would have been struck down by the same weapon that killed Siegmund. I would have met my end united with him! Far from Siegmund, Siegmund, from you! O let death cover me, when I think of it. If, on account of our escape, I am not to curse you, maiden, then hear my solemn plea: plunge your sword into my heart. Brünnhilde: Woman, you must live for the sake of love! Save the child that your received from him: a Volsung is growing in your womb! Sieglinde: Save me, brave girl! save my child! Shelter me, you maidens, [the other Valkyries] with powerful protection! Waltraute: The storm is approaching. Ortlinde: Flee, if you fear it. The Other Valkyries: Get the woman away, if danger threatens her. None of the Valkyries dares protect her. Sieglinde: Save me, girl! save a mother! Brünnhilde: Then quickly escape, and escape by yourself! I will stay here and face Wotan’s vengeance. At my side I will delay him here in his rage while you escape from his anger. Sieglinde: Which direction shall I take? Brünnhilde: Which of you sisters has flown eastwards? Siegrune: Away to the east stretches a forest: the Nibelung treasure there by Fafner carried. Schwertleite: He changed himself into the form of a dragon. In a cave he keeps watch over Alberich’s ring! Grimgerde: It isn’t a safe place for a helpless woman. Brünnhilde And yet from Wotan’s anger the wood would surely shelter her. The Master dislikes it and shies away from the place. Waltraute: Furiously rides Wotan to the rock. The Valkyries: Brünnhilde, listen to the thunder of his approach. Brünnhilde Hurry away, then, towards the East! Be brave and defiant, put up with all hazards, hunger and thirst, thorns and rocks. Laugh, whatever distress or suffering may plague you! This one thing you know and always remember: the noblest hero in the world, woman, you are carrying in the shelter of your womb. Keep for him the strong Sword’s fragments. From his father’s battlefield I luckily brought them. He will forge them anew and one day wield the sword. Let me give him his name,“Siegfried,” joyous in victory! Sieglinde: [at this point she sings the motive heard for the first time: victory through love] Oh, mightiest of miracles, most glorious of women. I thank you for your loyalty and holy comfort! For him, whom we loved, I will save the most loved (child). May the reward of my thanks one day smile at you! Farewell! tormented Sieglinde blesses you!

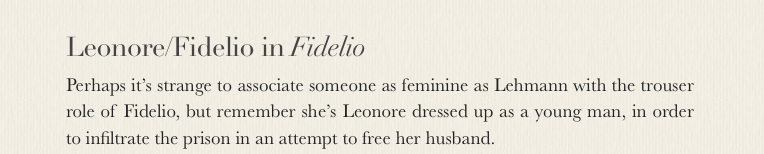

This 1927 recording was made during the same year that she took on this dramatically and vocally demanding role for the centenary year of Beethoven’s death. She continued to sing Fidelio with extraordinary success in Vienna, Hamburg, Salzburg, Berlin, Paris, Stockholm, Antwerp, and London. You’ll find an interleaved commentary of this aria in the chapter called Arias and Lieder.

When she sang Fidelio in Paris a critic there wrote: “…Mme Lotte Lehmann, who is the purest and most magnificent soprano of the Vienna Opera, absolutely surpassed herself, vocally and histrionically, in her dramatic rendition of Leonore. A delirious audience showered her with unending applause.”

“…Lehmann is one of the few who have realized the mysterious something which this opera contains; she is in tune with the magical things in the Beethoven language, she has come inwardly near to the soul of Fidelio in an astonishing process of artistic travail. For years we have experienced no Leonore in Hamburg who reached so deeply into our hearts….In acting as in song this Leonore was the glowing flame of the evening. Histrionically an accomplishment polished to the last degree, wherein technical mastery could be taken for granted. Feeling was everything, guided vocally by powerful impulses, yet under emotions of the highest kind. A sound-miracle [ein Klangwunder].” unattributed Hamburg critic, 1927,

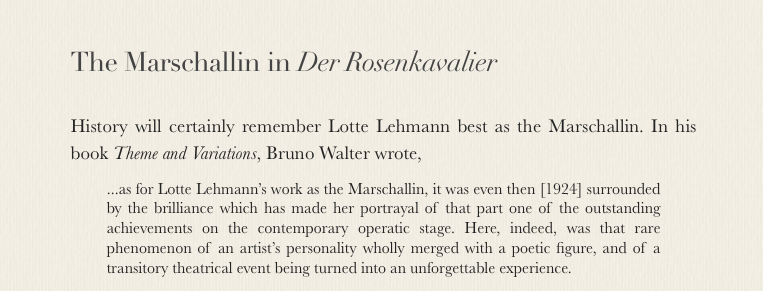

In 1935 Lehmann made the definitive recording of the role with which she became identified. The Vienna Philharmonic was conducted by Robert Heger. Here is an excerpt of the Marschallin’s Act I monologue. Note the speech-like quality with which Lehmann sings this.

Lehmann demonstrates in a master class the extended monologue from Der Rosenkavalier, found below with the English translation. It’s an historic moment for the world to view a video of Lehmann as the Marschallin.

We’ve selected one representative song that Lehmann sang from each of the major Lieder composers. And that brings us to one of her most-performed Mozart songs, “Das Veilchen” (the Little Violet) to the words of Goethe. Here’s a little story of the unnoticed little violet that Lehmann delights in telling.

Moving chronologically brings us to the many Beethoven Lieder that Lehmann performed. And instead of his serious side, we’ve chosen the lighter aspect of Beethoven. Lehmann seems to relish the situation of the cheeky boy stealing a kiss in this 1941 recording of “Der Kuss” (the Kiss).

One can fill four CDs with Lehmann recordings of Schubert Lieder; in another chapter we offer Winterreise. Here we’ve chosen a 1947 recording of the rather formal “An den Mond” (Geuss, lieber Mond) to Hölty’s words, not Goethe’s. The title can be translated as “To the Moon.” The Lieder expert Philip Miller considered this Lehmann’s best Schubert recording.

Besides the song cycles Dichterliebe and Frauenliebe und -Leben, Lehmann sang many other Schumann Lieder. Her mastery of the Lied can be heard in this 1941 CBS radio broadcast of Schumann’s “Der Nussbaum” (The Nut Tree) telling of the young girl who dreams of her impending marriage. Just listen to the intimacy Lehmann brings to the last words.

Lehmann devoted complete recitals to the Lieder of Brahms and recorded many Brahms songs, but none with more charm and character than this 1932 “Sandmännchen”(Little Sandman) which maintains its lightness in spite of the instrumental accompaniment.

On 18 October 1938 Lehmann sang an all-Wolf recital in New York’s Town Hall. Few singers at that time offered such a program. Furthermore, she had the audacity to begin this recital with Wolf’s most demanding song, Goethe’s “Kennst du das Land.” It’s vocally strenuous and for the pianist, almost a virtuoso piece. The familiar poem translates as “Do You Know the Land,” which may have had special appeal for Lehmann, who had only months before left her home in Austria shortly before the Nazi’s entered Vienna and annexed the country.

This whole recital was broadcast on AM radio. A fan placed a microphone in front of the radio’s speaker and recorded the recital on acetate discs. Luckily for music-loving history, these discs found their way to a secure archive at the University of Missouri, Kansas City. It is from that set of discs that Lani Spahr resurrected this immortal performance. Even with such sonic limitations, every nuance of the sung poetry is clear and heart-wrenching in its import. Though there is distortion, the piano part is also powerful.

Lehmann felt a deep connection with Strauss Lieder because she knew the composer personally and had even sung his songs with Strauss at the piano when visiting him at his cozy home in Garmisch. We’ve chosen “Du meines Herzens Krönelein” (You My Heart’s Little Crown), which was Lehmann’s last studio recording. At age 61, Lehmann’s way with every subtle shading is as evident as at any time in her career.

She sang in many operas that were composed in her time, but unheard in later years. In 1927 she created the title role of Heliane in Korngold’s Das Wunder der Heliane (The Miracle of Heliane). Here’s an excerpt from the opera’s most famous aria in which you’ll hear both the glorious sound of Lehmann’s voice, and the intensity of the drama. What a difference the newly invented microphone makes!

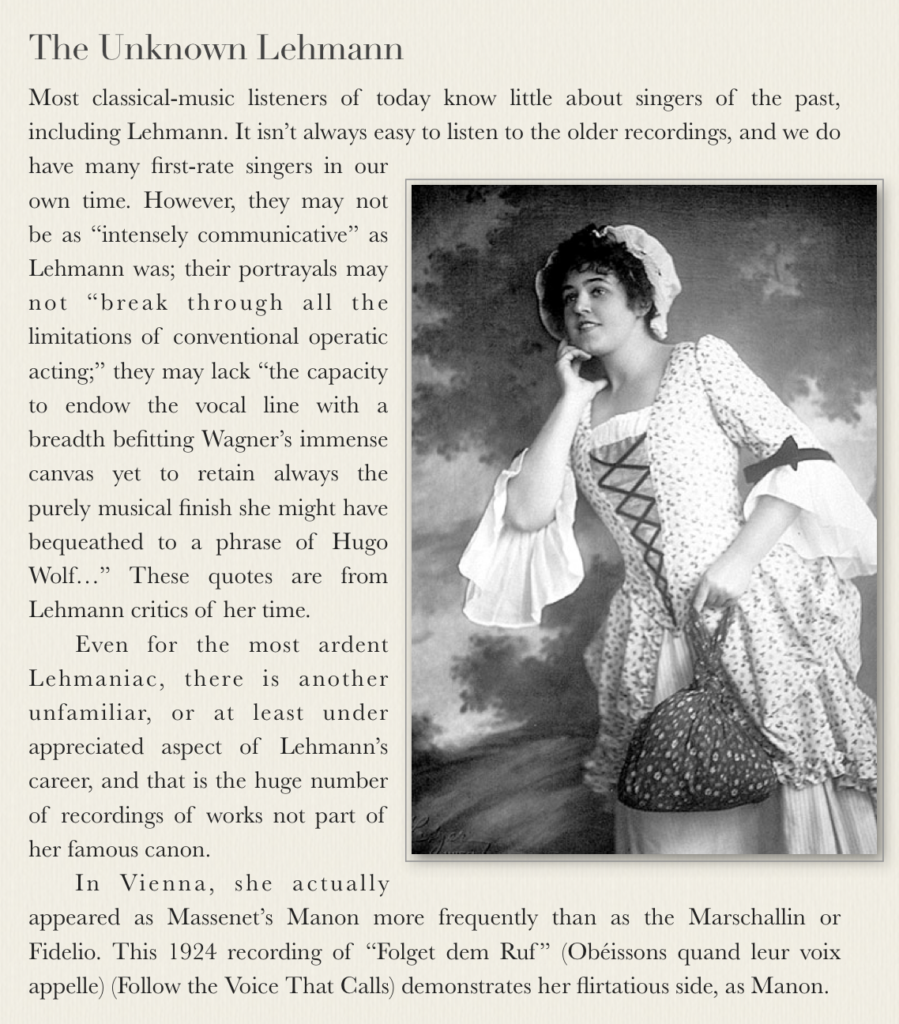

Lehmann sang the lead in Mignon by Ambroise Thomas, in both Hamburg and Vienna. The opera was originally written in French to the Goethe story. In German-speaking lands it was translated into German and it’s thus that we hear Goethe’s famous original poem “Kennst du das Land” in this 1930 recording. This is one of the earliest poems that the young Lehmann learned and she always delighted in the chance to recite it.

Lehmann also performed then-living composers’ Lieder that are seldom heard now. In 1932, for instance, she performed for the 50th birthday party for Josef Marx, given on stage in Vienna with the composer at the piano. In 1937 Lehmann recorded an ecstatic version of his “Selige Nacht” (Blessed Night) with Ernö Balogh, pianist. Though Marx isn’t well-known today, RCA Victor thought highly enough of him in 1937 to offer Lehmann the chance to perform this song.

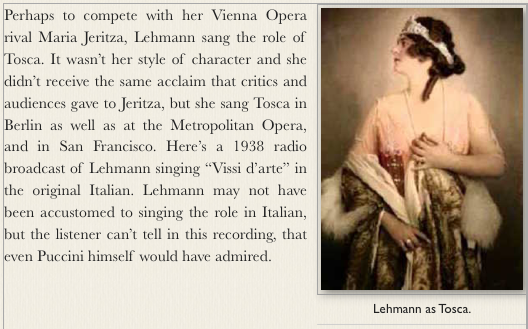

Another segment of Lehmann’s career that remains unknown is the familiar operas not usually associated with her. The demanding tessitura of Turandot seems beyond her lyric soprano range, but she sang the Vienna premier, and performed the role in Hamburg, Breslau, and Berlin as well. In this rare 1927 recording (082) you’ll hear Lehmann handle the high “C’s” with aplomb. You may also hear notes missing from the Ricordi score which have now been rediscovered and are again being performed.

Lehmann sang only one Verdi role, that of Desdemona in Otello. She performed it in Vienna, Budapest, Berlin, and London. In London, the demanding critic of the Gramophone wrote, “…Lotte Lehmann did so magnificently both as singer and actress that she rose to heights never attained here before…” Herman Klein and The Gramophone, edited by William R. Moran. In this 1932 recording (193), Lehmann sings the famous “Willow” aria that ends with Desdemona’s premonition of death.

She enjoyed great fame for her many-faceted portrayal of Eva in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger. Few singers in recorded history have ever portrayed a more impetuous Eva, as she greets Sachs, acknowledging their past love and her anticipated future. Even this 1920 recording (040) (microphones hadn’t yet been invented) captures much of Lehmann’s spontaneity. This almost improvised sounding aria is “O Sachs mein Freund” (Oh Sachs My Friend.)

Hermann Götz wrote Der Widerspenstigen Zähmung (inspired by Taming of the Shrew). Lehmann sang the opera a few times in Vienna and recorded the tuneful aria of Katharina in 1919 (028). She sang it in many concerts throughout the years, with great success. Though she didn’t encourage her students to sing “mixed” concert recitals, she often did so herself. Perhaps it was in accord with the wishes of her sponsors. There are many such “contemporary” operas that Lehmann sang in Hamburg and Vienna that just haven’t endured.

Though hardly known today, d’Albert’s Die toten Augen, was performed in Lehmann’s era and she was especially appreciated in the lead role as the blind Myrtocle in her years at the Hamburg Opera. Here’s what Beaumont Glass writes about that:

“Her most popular role of all, however, turned out to be Myrtocle in Die toten Augen by Eugène d’Albert. It is the story of a young Greek woman, blind since birth, who is miraculously given sight by the touch of Jesus Christ. The one thing she has longed to see is the face of her beloved husband who has always been very kind to her. She has never been told that he is monstrously ugly. When she sees him he is devastated. For his sake she stares at the sun until her eyes are blind again.

There are several extremely effective scenes and Lotte made the most of them. A tour de force was the moving pantomime in which she sacrifices the gift of sight which had shortly before filled her with such exultant ecstasy. Lotte showed in her face the enormous effort of will needed to keep looking into the sun in spite of searing pain, the bitter acceptance of the return of darkness, and the great love that motivated her renunciation. It was a scene of overwhelming spiritual power as she played it (and as she re-enacted it for her master classes in Santa Barbara forty-five years later).

There was one line that Lotte refused to sing. According to the score, when Myrtocle realizes that she can see, her first words are, “a mirror! a mirror!” Lotte could not accept that. She felt that vanity at such a moment diminished the character of Myrtocle and the glory of the miracle. D’Albert tried vainly to convince her that his libretto was psychologically right, that a blind person would first of all want to see what she looked like. But Lotte simply left out the line altogether and started with the ecstatic, hymn-like phrase, “Light! Light! Everywhere light!” Her performance was so deeply moving that d’Albert had gratefully to admit that she was right.

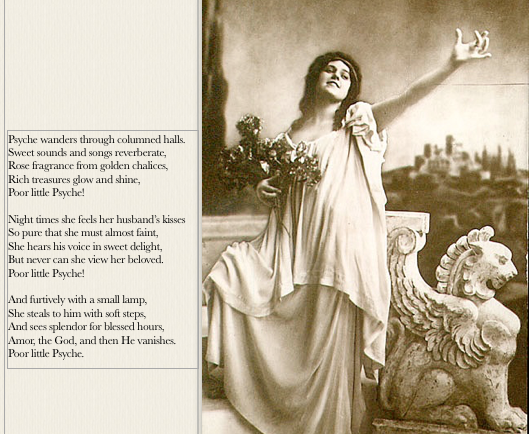

An aria from Die toten Augen, “Amor und Psyche,” practically became Lotte’s theme song for a while. It was the most frequently requested encore at her concerts whenever she came back to Hamburg. Myrtocle was the role of her farewell to Hamburg. It was her 526th performance there since her debut in 1910.”

An aspect of Lehmann’s career that some strictly “classical” music lovers find compromising is her participation in operetta and the popular music of the time. She sang various operettas in Hamburg, Vienna, and Die Fledermaus even in London. She recorded music from that as well as other operettas. She seems to have had a lot of fun while singing the following excerpt from Otto Nikolai’s Merry Wives of Windsor. In this 1932 recording you’ll hear her conniving with her friends on how to trick Sir John: “Er wird mir glauben” (He’ll Believe Me)(190).

Frau Fluth gathers her pals together to play a prank on the flirtatious Sir John, the fat glutton. She will pretend to love him and he’ll fall for it, but it’s all in fun. “A happy sense of humor spices up life, and to forgive is as good as the joke. After all, real love and faithfulness stay in the heart.

Now hurry here, jokes, bright humor, the greatest pranks, cunning and bravado. Nothing is too wicked, if it serves to punish men without pity. That is a group, so awful, that one cannot complain enough about them. Before all others that fat glutton, who wants to seduce us. Ha ha ha ha! He should pay the penalty. But when he comes, how will I have to behave? What will I say? Stop! I already know! Seducer! Why do you set a trap for a virtuous spouse? Why? Seducer! The outrage will never subside. No, never, my anger must be your punishment. However, a woman’s heart is weak. You complain so pathetically about your pain. You sigh, my heart becomes weak. No longer can I be cruel, and I confess it, shamefully blushing, to you, my knight. I love you. I love you. He will believe me, performing I can do very well. A bold risk is it indeed, only for fun may one allow it herself. Happy sense and humor spices up life and to forgive is as good as the joke. So for fun one may lie. Real love and faithfulness stay in the heart. Therefore full of trust, dare I to do the deed. Happy women, yes, who know their own counsel.

In 1929 Lehmann even sang a real pop hit, Hans May’s “Der Duft, der eine schöne Frau begeitet” (The Aroma that Accompanies a Beautiful Woman). Listen for the real Viennese rubati that she brings to this song. (Just try conducting a square 4/4.)

In her old age Lehmann would listen to only one of her recordings and that was this light, Bavarian-dialect folk song “Zuschau’n” (Peeking) which she had recorded when she was 43.

Some listeners find Lehmann’s rather large output of devotional music (recorded in her early years) a bit embarrassing, but one hears conviction in these recordings that belies her own rather ambiguous religious beliefs. In this 1928 recording Lehmann’s voice balances well with the organ and sounds almost like an intimate prayer on Louis Roessel’s “Wo du hingehst” (Where You Go Forth) (134).

The most troublesome (even annoying) recordings to hear today are the Lieder that Lehmann recorded for Odeon with salon-orchestra accompaniment. The record companies didn’t think that the buying public was getting its value if there was only a piano. Not only does this violate the composers’ intentions, but the quickly written and poorly played arrangements can sound soupy and corny to our ears. Compare the orchestra version of the 1929 Strauss “Ständchen” (Serenade) (156) with the 1941 version with the original piano accompaniment (353).

Even Lehmann fans may not know that she toured with Lauritz Melchior, performing shared recitals. They were even booked into Carnegie Hall. RCA made a recording (sadly with orchestra) of some of the Schumann duets that were featured on the tours. But there’s still much to enjoy in the following 1939 recording of “Er und Sie” (He and She).

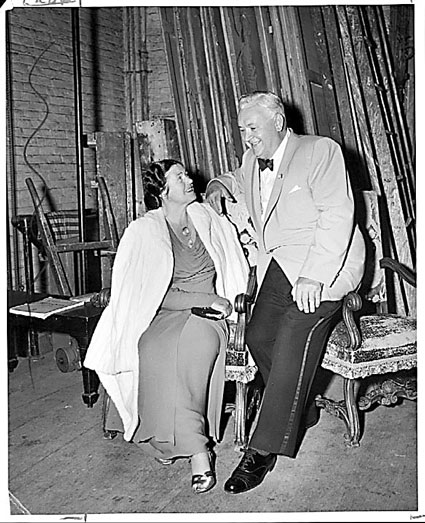

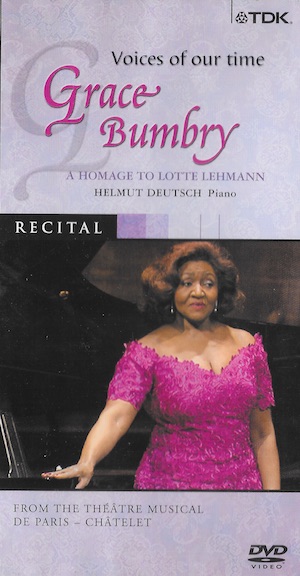

Her students (now mostly retired) have many Lehmann stories to tell and some, like Marilyn Horne and Grace Bumbry, have even given recitals honoring Lehmann. Benita Valente, a Lehmann student in her youth, wrote the Foreword to Volume II of this series of presentations. Another student, the late Carol Neblett, wrote the Foreword to Volume V. Mildred Miller and Lois Alba wrote the Forewords to Volumes VI and VII (Interviews).

Many people who closely follow Lehmann’s singing don’t realize that she recorded two LPs of poetry readings as well as spoken excerpts from Der Rosenkavalier. You can hear a sample of each: Goethe’s “Der du von dem Himmel bist” (You Who Are From Heaven) and a portion of the Marschallin’s Act 1 monolog.

So much for the “unknown” side of Lehmann. Her fame, if that is the right word, is sustained by the many studio and live recordings that are frequently re-released. In 2018 Marston Records published her acoustic recordings and in 2019 that company offered Lehmann’s electric recordings made in Berlin from 1927–1933. There are other presentations of various Lehmann items on YouTube, eBay, and thematic collections that may be downloaded from the internet.

Lehmann biographies continue to be written (see Bibliography) and several of the books she wrote remain in print, all of which helps preserve a degree of her “legendary” status. You can read some of her poetry and prose in the chapter called Last Word.

Critics continue to refer to the Lehmann standards that she set in the roles of the Marschallin, Sieglinde, and others. For instance, in the Jan/Feb 1992 issue of Fanfare, David Mason Green wrote: “Lehmann is for me…the ideal Mignon, but I like her Puccini interpretations almost as well.”

Reference is also frequently made to her Lieder recordings which are models for the kind of balance between the music and the words’ expressivity that was so important for Lehmann. In Gramophone magazine Alan Blyth reviewed a CD compilation of her Lieder:

“Once again one exclaims, and is heartened by, the warmth of tone and generosity of spirit in all these interpretations; also the total exclusion of the reticence and insistence on good vocal manners that so often weaken the interpretations of her successors….”

Lehmann’s success as a teacher of interpretation is unparalleled in the annals of opera and Lieder singers who have also taught. See both the contents of The Third Career as well as the list of her students at the end of that chapter. You can hear recordings of her master classes and private lessons in the interpretation of Lieder, Song Cycles, and Arias & Scenes in Volumes III-V of this series.

Lehmann spoke often and with pride of enjoying three lives—as an opera singer, a recitalist, and a teacher.

She accomplished all three careers with distinction. Though today her name is generally unnoticed and unrecognized, for the vitality, commitment, and sheer beauty she brought to her art, Lotte Lehmann deserves all the full legendary status that her talent and hard work engendered.

Typical of the kind of praise she continues to inspire, in the Sept/Oct 1990 edition of Fanfare, Marc Mandel wrote:

“Lehmann’s uniquely characteristic warmth and conviction help bring each heroine vividly to life; she projects a keen awareness of Tosca’s situation, honest innocence in “Un bel dì,” touching plaintiveness in Mimì’s narrative, and apt wonderment at Turandot’s newfound humanity. For that matter, the Chénier aria on the second disc is equally persuasive, even as juxtaposed against the more standard Lehmann fare of Wagner and Richard Strauss.”

The last sentences of Dr. Kater’s 2008 Lehmann biography reads:

“In human terms, Lotte Lehmann undeniably led a full life, over mountain peaks and through valleys. But it was as one of the greatest singers of the twentieth century, if not of all time, that she made music history.”