Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy: Volume 1

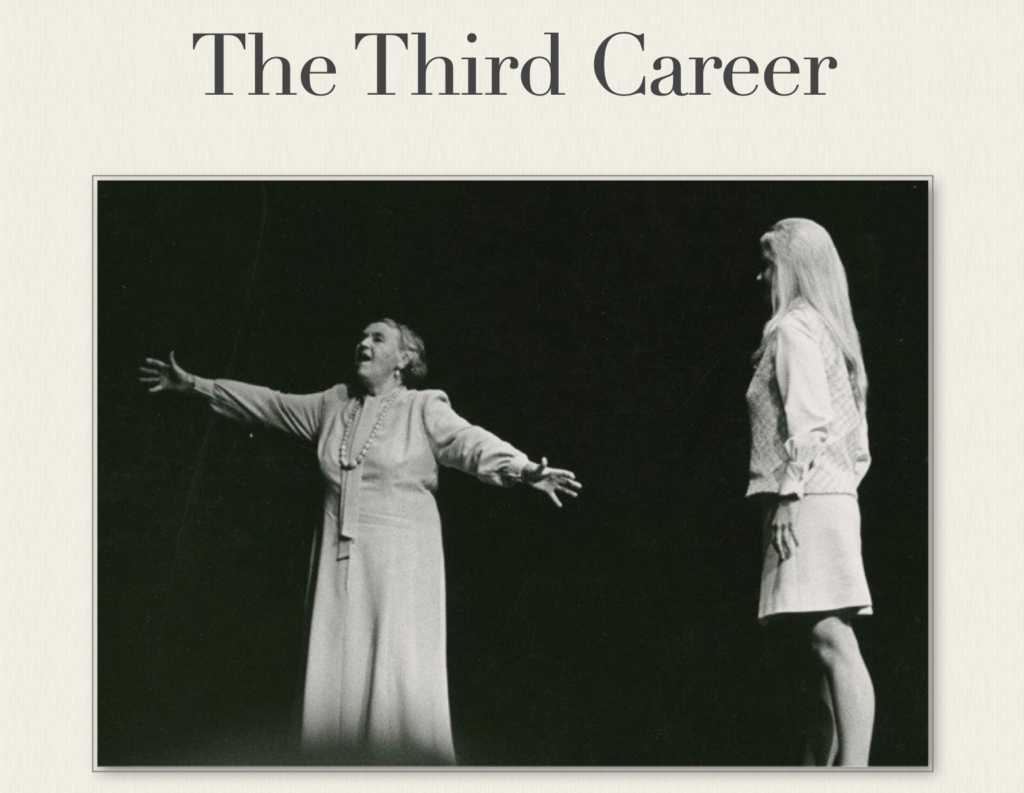

Lotte Lehmann enjoyed her third career just as much as she did her first two. Kathy Brown’s 2012 book Lotte Lehmann in America: Her Legacy as Artist Teacher, with Commentaries from Her Master Classes thoroughly describes Lehmann’s teaching methods.

Presented here are audio and video documents of her teaching, and examples of her students’ singing, as well as their comments on Lehmann. You’ll find extensive audio of Lehmann’s master classes in Volumes III–V.

In the following video excerpt, Lehmann reveals the secret to her great success, in both Lieder and opera singing. There are great artists who don’t necessarily subscribe to this philosophy, but Lehmann obviously did and she’s suggesting to her students that they should consider the same principle.

Without singing a note, Lehmann demonstrates how the singer can respond to a piano introduction. Notice that the hands don’t hang limply down at the side of the body, and you sense that she is hearing the importance of every note. But really, there isn’t much motion at all. The singer listens to the piano and reacts naturally.

Lehmann demonstrates—at the age of 73 and without much voice—the various elements of the Robert Schumann Lied, “Ich kann nicht fassen, nicht glauben” (I can’t understand it, not believe it) from his cycle, Frauenliebe und -Leben. This is the moment in the story at which the young girl knows that he loves her.

The mysterious and pleading quality that Lehmann suggests are found in the words of one of Goethe’s most famous lyrics, “Kennst du das Land.” Here are the words she quotes, in English translation:

Do you know the land where the lemon trees blossom? Among dark leaves the golden oranges glow. A gentle breeze from blue skies drifts. The myrtle is still, and the laurel stands high. Do you know it well?

A recitative is that portion of an opera in which a lot of information is offered without the aid of much melody. It’s usually overlooked, because singers want to get to the aria. Here, Lehmann takes the time to demonstrate the words of the Countess, in the Marriage of Figaro. Though Mozart set Da Ponte’s Italian words, it was the tradition in German-speaking lands to sing everything in the language of the audience.

The student has performed the most famous aria from Weber’s Der Freischütz. Lehmann illustrates with her body and face, a response to the music and situation when there’s no singing. The character Agathe is impatiently waiting for her boyfriend, whom she hopes has won the shooting contest.

In the following Brahms Lied, Lehmann says that the 17th-century poet Paul Fleming’s words of the infatuated lover are unimportant and must just tumble out. Despite this admonition, she demonstrates with her usual clear diction, but “sings,” as usual during her teaching years, an octave below the soprano key.

O Schönste der Schönen benimm mir dies Sehnen, Komm, eile, komm, komme, du süße, du fromme! Ach, Schwester, ich sterbe, ich sterb’, ich verderbe, Komm, komme, komm, eile, benimm mir dies Sehnen, O Schönste der Schönen!

Oh fairest of the fair, free me of this longing, Come, hurry, come, you sweet, innocent! Ah, sister, I die, I die, I perish, Come, hurry, come, free me of this longing, Oh fairest of the fair!

A New York City critic voiced a negative opinion when Mme Lehmann sang an “All-Brahms” Town Hall recital. Today we would welcome such a chance to appreciate the many-sided nature of Brahms Lieder. Lehmann could milk the tragic songs, and make one laugh at the light-hearted ditties. Luckily many of the acetates of these recitals have been located, and the serious Lehmann fan can find them available in the box set that Music & Arts released.

Lehmann discusses the involvement of the whole body when singing, but cautions against extraneous or meaningless motion. I have witnessed Lehmann demanding of a student the most sensitive response to the words, psychological subtext, and complete engagement from the eyes to the feet.

In this demonstration of the Robert Schumann Lied, “Schöne Wiege meiner Leiden,” Lehmann illustrates the broad spectrum of responses to each line of this strophe. She doesn’t have the words in front of her and makes up a few as she goes along.

Doch du drängst mich selbst von hinnen, bittre Worte spricht dein Mund; Wahnsinn wühlt in meinen Sinnen, und mein Herz ist krank und wund.

Yet you yourself pushed me away from you, bitter words at your lips; Madness filled my senses, and my heart is sick and wounded.

Classical singers often think that the smooth singing they seek can be obtained by connecting the notes with a slide. Here Lehmann observes that this habit makes a song sound sentimental and must be avoided. In the past, many singers, including Lehmann, used this portamento effect in their performances, weakening their presentation.

This demonstration of a Brahms song allows us to hear and see just what made Lehmann so appealing in her recital performances. Each phrase of Ludwig Uhland’s poem elicits a reaction from her, whether vocal or physical, and this response doesn’t cease when she’s finished singing the words.

Das tausendschöne Jungfräulein, Das tausendschöne Herzelein, Wollte Gott, wollte Gott, ich wär’ heute bei ihr!

That thousand-times beautiful girl, That thousand-times beautiful little heart, Would to God, that I could be with her today!

In this brief scene from Lohengrin, Lehmann summons up all the evil inherent in Ortrud’s character and shows that the whole body must engage in the thought being expressed in singing.

Könntest du erfassen, wie dessen Art so wundersam, der nie dich möge so verlassen, wie er durch Zauber zu dir kam!

Have you never grasped that he of such mysterious lineage might leave you in the same way as by magic he came to you?

Here are some individual songs and arias with Lehmann teaching their interpretation in master classes held at Cal Tech in Pasadena in 1952. In Wolf’s “Auf einer Wanderung” Lehmann demonstrates a few words in her soprano voice and in “Du denkst mit einem Fädchen” emphasizes the fun. The two Strauss songs, “Heimliche Aufforderung,” and “Zueignung” allow her to share her decades of performing experience of these Lieder.

In the following excerpt “Du bist der Lenz” from Wagner’s Die Walküre, Lehmann actually demonstrates in full voice years after she had “lost her voice” or sung publicly. The second opera scene is from Der Rosenkavalier, and one of the singers is Marilyn Horne. The third scene is from the opera that Lehmann performed more than any at the Vienna Opera: Massenet’s Manon.

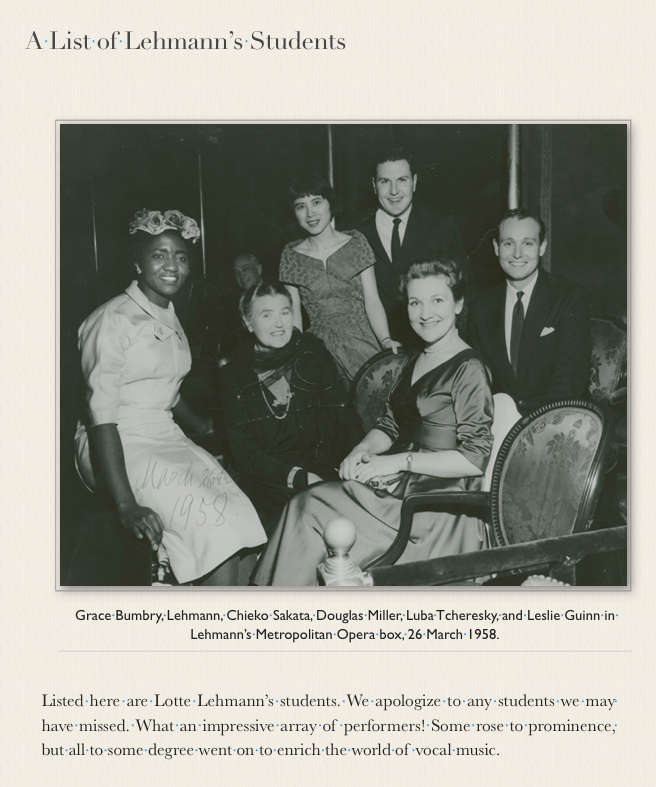

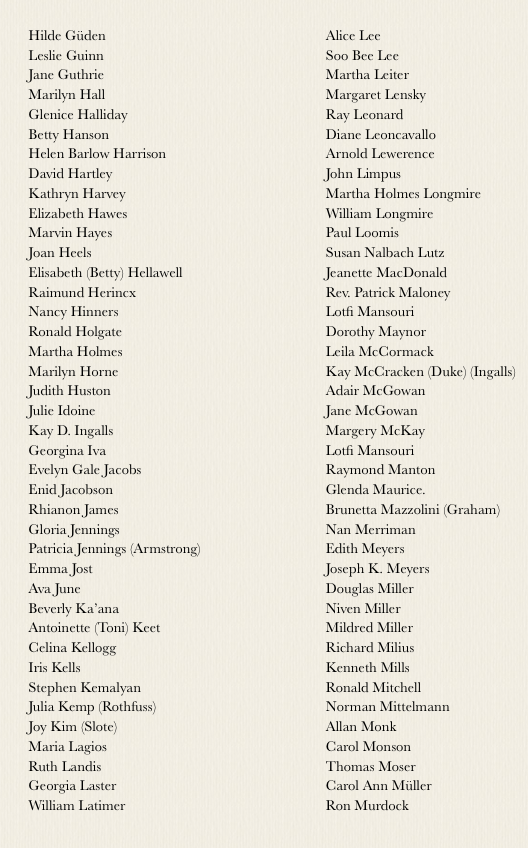

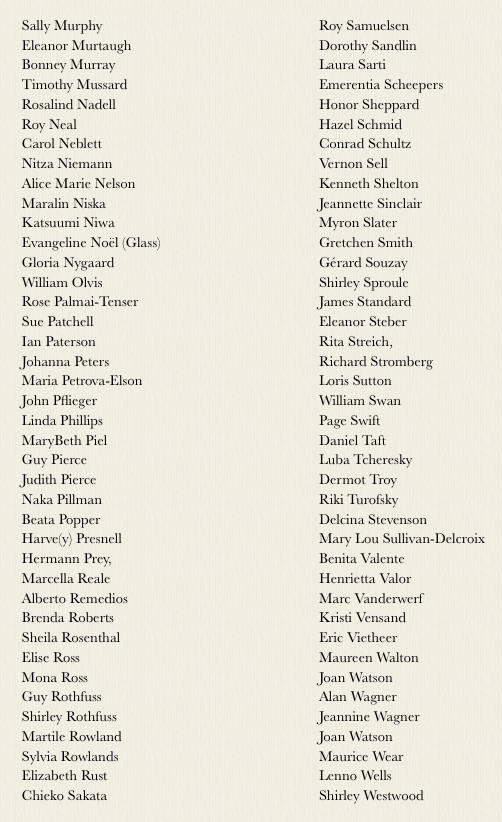

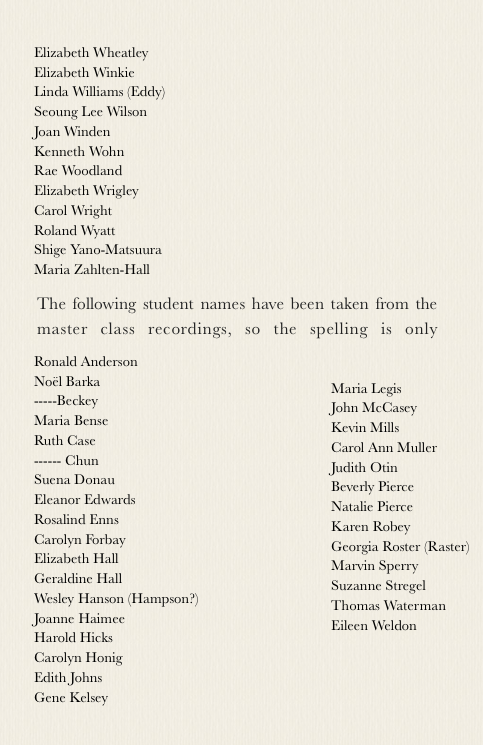

Lehmann’s Students

Many of Lehmann students went on to world fame and others to highly successful careers. The most famous of her students, Marilyn Horne and Grace Bumbry, specialized in opera. Horne became an excellent bel canto singer, who, though she sang the verismo title role of Carmen, concentrated her talents in the coloratura characters found in operas by Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini.

Bumbry, like Horne, sang in major opera houses throughout the world, but lived in Europe. Her fame rests on the dramatic mezzo soprano roles associated with Verdi. Both Horne and Bumbry sang at the White House and were recipients of the Kennedy Center Honors award. One can easily buy CDs and DVDs of these women in their prime as opera singers. Their work as Lieder singers is less well known. Beaumont Glass is Bumbry’s pianist in Wolf’s “Anakreons Grab.”

Other exceptional pupils included Benita Valente and Mildred Miller, who both appeared extensively at the Metropolitan Opera and also sang recitals. Valente was lauded for her Mozart and Handel singing, though she also sang certain Verdi roles. Her work in chamber music settings earned her the honor of having several pieces written for her voice and string quartet. Cynthia Raim is her pianist for “Die Nacht” by Strauss.

Miller sang mainly at the Metropolitan Opera from 1951–1974, often associated with the pants roles of Octavian, the Composer, Nicklausse, and Prince Orlofsky. She sang an amazing 338 performances there.

She tells of the first time she heard Lehmann and mentions the Brahms Lied, “Mein Mädel hat einen Rosenmund,” which you can hear Lehmann sing. Then Miller speaks of the importance, for her, of the Schumann Lied, “Aus der Heimat…,” which she sings with John Wustman, piano. Lehmann was so proud of her that she flew to New York when Miller made her Town Hall debut.

Though best known for her many years of teaching in Japan, Marcella Reale was a successful opera singer with a repertoire of over sixty roles. Focusing on verismo roles, Reale performed widely in Europe and Japan, singing the role of Butterfly 300 times. Listen to her sing “Vissi d’arte” from Tosca.

Lehmann’s final pupil was Jeannine Altmeyer, whose excellence in Wagner operas has been preserved on DVDs. Her European performances included Salzburg, Covent Garden, and Bayreuth. After her retirement, she recorded a Lied (Schubert’s “Gretchen am Spinnrade”) that she’d studied with Lehmann. Val Underwood is her pianist.

Carol Neblett studied privately with the then-elderly Lehmann. She enjoyed a worldwide career as an opera soprano and her recording of Korngold’s Die tote Stadt has become a classic. She had great success at the New York City Opera, and sang as well at the Metropolitan Opera. Not famous for her Lieder, she did perform a tribute recital to her teacher for the Lehmann Centennial held at UCSB in 1988.

Luba Tcheresky was an alumna of Lehmann’s Music Academy of the West for three years of master classes. She sang opera for a short time in Europe and in many genres in the United States. As with most of Lehmann’s students, she taught, in her case privately, for many years in New York City. Here’s a live performance of her singing Schumann’s “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai” with Beaumont Glass, piano.

One of Lehmann’s most dedicated students was the Canadian soprano Shirley Sproule, who studied at the MAW in the summer seasons, as well as the short-lived winter ones. She enjoyed a minor career in Europe and taught later in Canada and the U.S. Sproule was almost 80 years old when she recorded her tribute, “Der Himmel hat eine Träne geweint” (Heaven Cried a Tear) by Schumann with Paula Fan, piano.

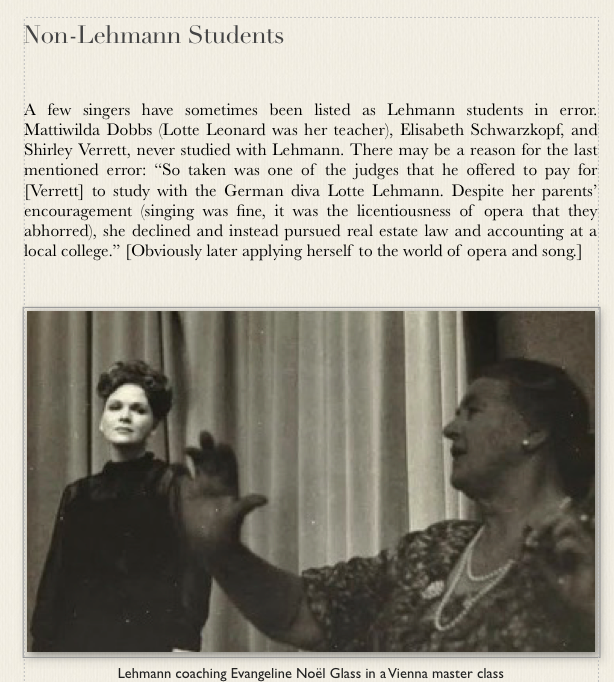

Evangeline Noël Glass studied at the MAW, appearing on the 1961 VAI opera and Lieder master class videos. She sang in such classes in Europe as well, where she taught with her husband, Lehmann’s biographer, Beaumont Glass.

The male students among Lehmann’s master classes and private lessons didn’t achieve the same fame as the women, but were able to enjoy satisfying careers. William Cochran’s beautiful tenor voice is heard here as Siegmund. The Salt Lake Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Maurice Abravanel (another MAW connection). He sang in major opera houses in the United States and at Covent Garden, and opera companies in Frankfurt, Munich, Hamburg, and Vienna.

William Olvis was born in Los Angeles. His talents carried him from Hollywood to New York, on to Europe, and back to New York, where he performed with the Metropolitan Opera. The excerpt is from the movie based on the life of Sigmund Romberg called Deep in My Heart (1954). But Olvis also sang opera, as you’ll hear in the “Gewitter und Sturm” aria from Der fliegende Holländer.

Harve Presnell had a very successful career in Broadway and in Hollywood movies, most notably The Unsinkable Molly Brown. Presnell had sung with orchestras and opera companies, but his fame was due to his work in musical theatre and later as a character actor in films. We have a chance to hear him “classical” in the excerpt from Orff’s Carmina Burana, conducted by Eugene Ormandy.

In the following tracks we can hear Norman Mittelmann talk about studying with Lehmann and then hear him sing Schumann’s “Die beiden Grenediere” with Gale Enger on piano recorded in 2005, long after he’d retired. Mittelmann began singing opera in Lehmann’s productions at the MAW. In 1958 he made his debut in his Canadian homeland and later sang in major European and North and South American opera houses. Mittelmann made his Metropolitan Opera debut in 1961 and sang there for the next 20 years.

One of the students for whom Lehmann held the most hope was Lincoln Clark, who expanded his career, and gradually left singing behind. We’ll let him tell the story.

The fame of Lehmann’s student Lotfi Mansouri was not at all as a singer, but as a director of operas. His work with the Canadian Opera Company, as well as the San Francisco Opera brought him deserved recognition. Mansouri was responsible for the introduction of surtitles, which have done so much to make opera successful. His memories speak fondly of his work at the Music Academy of the West.

There are many singers who worked only peripherally with Lehmann. Marni Nixon is most famously known as the singing voice behind the star in the movies The King and I, West Side Story, and My Fair Lady. But her singing and acting career spanned Broadway, opera, concerts, and recordings both in avant-garde and standard repertoire. Her memory of working with Lehmann includes one under-appreciated element of singing: subtext. At the age of 75 she recorded Schoenberg’s cabaret song “Galathea” with pianist Thomas Bagwell. A nice further connection: they recorded in New York’s Town Hall, where Lehmann felt so at home.

Long before Lehmann taught at the Music Academy of the West, she coached many singers, including Jane Birkhead, Eleanor Steber, Risë Stevens, Rose Bampton, Nan Merriman, Dorothy Maynor, Anne Brown (the original Bess in Porgy and Bess), and Jeannette MacDonald.

During Lehmann’s Music Academy of the West years, and privately thereafter, star students included those mentioned above, as well as Karan Armstrong, Judith Beckmann, Kay Griffel, and Maralin Niska.

Manhattan School of Music students in the 1965 Town Hall master class included: Marc Vanderwerf, Barbara Blanchard, Celina Kellogg, and Glenda Maurice.

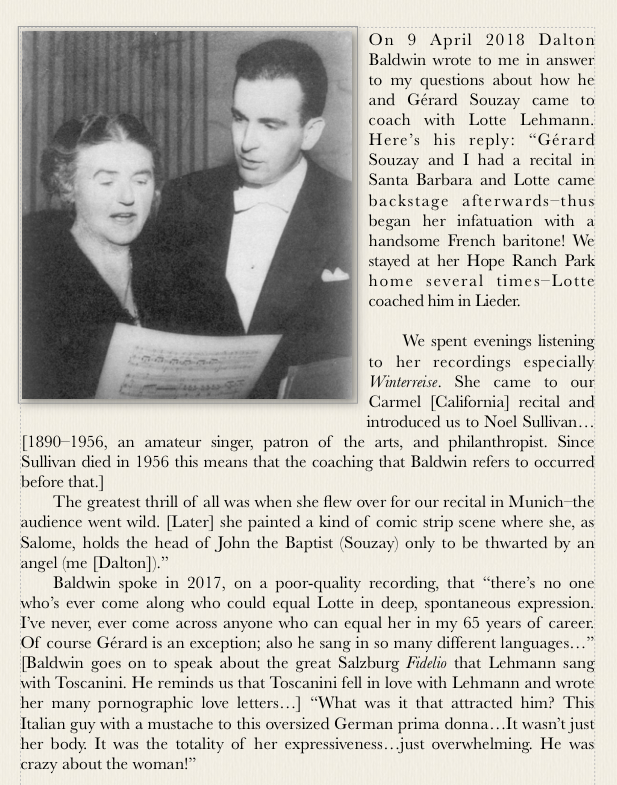

Established singers who valued Lehmann’s coaching included Hermann Prey, Gérard Souzay, Hilde Güden, Janet Baker, Thomas Moser, Rita Streich, Raimund Herincx, and Alberto Remedios.

Lotte Lehmann was the director/advisor of the 1962 Der Rosenkavalier for the Metropolitan Opera. For that occasion she coached the famous cast of females that included Régine Crespin as the Marschallin, Anneliese Rothenberger as Sophie (whom LL called the best Sophie in the world) and the reluctant Hertha Toepper, as Octavian.

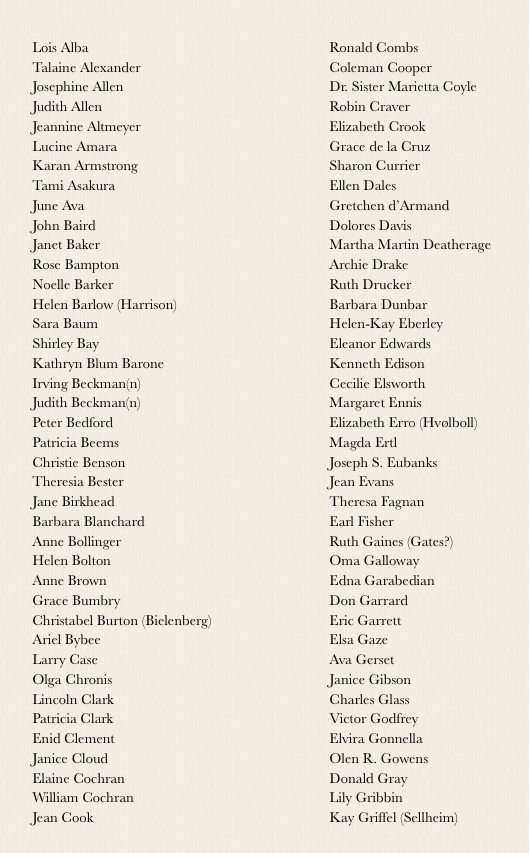

We look with some dismay at these names, because many of them, sadly, have already died.

In the following list Alan Monk should be Terence Monk. Also Betty Hanson was better known as Bette Hanson.