Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy: Volume 1

Asleep on her sofa after driving my baritone friend from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, I could never have guessed that a music lesson with this old German lady would change my life. I certainly didn’t snooze during any more of these lessons in the interpretation of opera roles and songs, for Lotte Lehmann opened my ears and mind to the classical vocal world. My baritone friend, Katsuumi Niwa, returned to Japan a few years later to enjoy a satisfying singing career. I continued my work as a double bassist but with what developed into an obsession with the life and recorded legacy of Lotte Lehmann.

Memorable Moments in Lehmann’s Life

Lotte Lehmann was born on 27 February 1888 in Perleberg, a small town in northern Germany. Her father was a civil servant, and it was his fondest hope that his daughter would someday follow in his footsteps. Above all, she must have a position that entitled her to a pension. Though her family knew next to nothing of classical music, Lotte was allowed to take piano lessons. One day a neighbor heard her singing around the house and persuaded her parents to let her audition for the Royal High School of Music in Berlin. She entered and practiced diligently the sometimes-limiting methods (such as singing with a stick between the teeth to hold the mouth open). During this time she frequented the top gallery of the opera house. Her initial studies came to a halt when she was rejected for being without talent!

Salvation occurred when Lotte wrote Mathilde Mallinger, who many years earlier had been Wagner’s first Eva in Die Meistersinger. It was she who gave Lehmann the technique and refurbished self-confidence she needed.

In 1910, after a year and a half with Mallinger, Lotte signed her first contract: a beginner’s engagement with the Hamburg Opera. She began as the Second Boy in The Magic Flute, moving to another comprimario role as a Page in Tannhäuser four days later.

By 1911, she’d already sung Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier. The next year Hamburg saw Lehmann sing with conviction the staring role of Elsa in Wagner’s Lohengrin and in 1914 she made her first recording of arias from that opera (001). These three-digit numbers refer to the Discography.

Also known as “Elsa’s Dream” she relates a dream in which a knight arrives to defend her. “Alone in dark days I prayed to God….my knight shall save me.”

In December 1913 an agent from the Vienna Opera visited the Hamburg Opera to hear the tenor singing in Bizet’s Carmen. But he heard Lehmann sing the role of Michaëla in that opera and hired her instead. Here’s her recording of that life changing aria.

“Ich sprach, dass ich furchtlos mich fühle” (Je dis que rien ne m’épouvante). In Germany and Austria, no matter the original language, everything was sung in German. Michaëla sings that, in spite of appearing in the smuggler’s lair to find José and relay his mother’s message, nothing can scare her, for God protects her.

In 1914 Lehmann sang the role of Eva in Die Meistersinger as a guest at the Vienna Opera. And here’s a 1916 recorded excerpt from that opera with the great Sachs of the time, Michael Bohnen, joining Lehmann. She greets him with the words “Gut’n Abend, Meister.” In spite of the sonic limitations (no microphone!) one hears a lot of personality from both singers.

Translation:

Eva: Good evening, Master! Still so busy?

Sachs: Ah, child! Dear Eva! Up so late!

And yet, I know why so late:

the new shoes?

Eva: How wrong you guess!

I haven’t even tried on the shoes yet;

they are so beautiful and richly adorned

that I haven’t dared to try them on.

Sachs: But tomorrow you’ll wear them as a bride?

Eva: Who might be the bridegroom?

Sachs: Do I know that?

Eva: How does he know that I’m to be a bride?

Sachs: Oh, that! The whole town knows.

Eva: Well, if the whole town knows,

then friend Sachs has good authority!

I thought he [Sachs] knew more.

Sachs: What should I know?

Eva: Well, think! Must I tell you?

Am I so stupid?

Sachs: I didn’t say that.

Eva: Then you’re shrewd?

Sachs: I don’t know.

Eva: You know nothing? You say nothing? Well friend Sachs,

now I truly know that tar isn’t wax.

I would have thought you sharper.

Sachs: Child! Both wax and tar are familiar to me:

with wax I coat the silken threads

with which I made your dainty shoes:

today I am making shoes with thicker yarn,

and tar is required for a rougher customer.

Eva: Who’s that? Someone important?

Sachs: Yes, indeed!

A master proud, intent on wooing,

He plans to be sole victor tomorrow:

I must finish Herr Beckmesser’s shoes.

Eva: Then take plenty of tar for them:

then he will stick to it and leave me in peace!

Sachs: He assuredly hopes to win you by his singing.

Eva: Why he then?

Sachs: A bachelor—

there are few of them about here.

Eva: Might not a widower be successful? [She means Sachs.]

Sachs: My child, he’d be too old for you. [He means himself.]

Eva: How so, too old? Art is what matters here!

Let him who understands it woo me.

Sachs: Dear Eva, would you mock me?

Eva: Not I! It is you, who are making excuses!

Admit that you are fickle.

God knows who may dwell in your heart now!

Yet I thought I’d been there for many a year.

Sachs: Because I liked to carry you in my arms?

Eva: I see, it was only because you were childless.

Sachs: I once had a wife, and children enough.

By the time that Lehmann was supposed to sing full time in Vienna, she’d become so greatly admired in Hamburg, that it was difficult to leave. Hamburg fans found Lehmann’s performance of the role of the blind Myrtocle in d’Albert’s Die toten Augen especially appealing, and her aria “Psyche wandelt durch Säulenhallen” marked her June 1916 farewell to Hamburg.

Translation:

Psyche wanders through columned halls. Sweet sounds and songs reverberate, Rose fragrance from golden chalices,

Rich treasures glow and shine,

Poor little Psyche!

Night times she feels her husband’s kisses So pure that she must almost faint,

She hears his voice in sweet delight,

But never can she view her beloved.

Poor little Psyche!

And furtively with a small lamp,

She steals to him with soft steps,

And sees splendor for blessed hours, Amor, the God, and then

He vanishes.

Poor little Psyche.

Austria was enduring wartime privations by the time Lehmann sang as a full-time member of the Vienna Opera, but on 8 August 1916, that faded into insignificance for her as she performed the role of Agathe in Weber’s Der Freischütz. Listen to the smooth line she maintained in its key aria that she recorded in 1917. In The Grand Tradition, John Steane writes: “When she sings ‘O wie hell die gold’nen Sterne’ we look out with her and see them [the golden stars]; when the clouds thicken over the forest, darkness closes in on the tone and we see that, too. Then there is the excitement, the radiance.”

During the next twenty-one years, the Vienna Opera was Lehmann’s home. Certainly she sang throughout Europe, South and North America, but she always enjoyed returning to the cozy feeling of shared triumphs (and failures) of the Vienna Opera. In Vienna she sang the many standard as well as newly composed operas, embarked on her recital career, and married.

Though she’d recorded a lot in Berlin, Lehmann recorded her two most famous, even iconic, roles in Vienna: the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, and Sieglinde in Die Walküre.

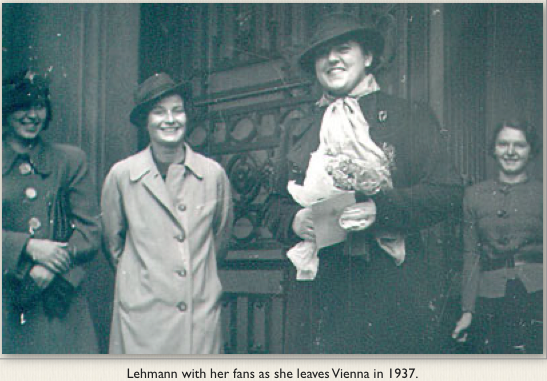

When in November 1937 it looked as if the Nazis were about to take Austria, she sang a few opera performances, a recital with Bruno Walter at the piano, and left for the U.S.

And though she recorded it a few years later, “Wien, du Stadt meiner Träume” (Vienna, City of My Dreams) held deep meaning for her and spoke often about her time there.

“My heart and my mind long for Vienna, for Vienna as it weeps, as it laughs. That’s where I know my way, that’s where I’m at home by day and even more at night. And no one stays cold, be he young, be he old, who knows Vienna as it really is. If I’d have to leave this beautiful place my yearning would never end. Then I’d hear a faraway song, sounding & singing, that entices and draws me. Vienna, you alone will always be the city of my dreams. There, where the old houses are, there, where the lovely girls walk. Vienna, you alone will always be the city of my dreams. There, where I am happy and delirious is Vienna, my Vienna.”

In Vienna Lehmann had bought a home as well as one for her parents. Her garden was famous for the rose plants, which she encouraged from her fans, rather than bouquets which so quickly wilted. After the Anschluss the Nazis made sure to tear out those famous rose bushes.

After emigrating to America, Lehmann performed her world-famous roles at the Metropolitan Opera, as well as at the Chicago and San Francisco opera houses, while broadening both her recital repertoire and its depth of interpretation. In America she recorded no more opera, but made many Lieder, mélodie, and even English, and American song recordings.

By the time she had sung her last opera role in 1946, Lehmann was well established as the foremost recitalist in the world. Her usual schedule of three sold-out recitals in New York’s Town Hall was expanded to as many as eight. Many of these were broadcast on the radio and thus preserved by amateur recording buffs. Here’s one of these off-the-air recordings: a portion of Mendelssohn’s “Gruß” (Greeting).

In 1948 she appeared in a Hollywood film, Big City, playing opposite the child star Margaret O’Brien. The president of MGM called Lehmann “the greatest screen mother in the world,” but she made only this one feature film.

Lehmann’s famous (but unannounced) farewell recital in New York’s Town Hall, on 16 February 1951, was recorded. She made a moving impromptu speech. During the encore she broke down at the last line of Schubert’s “An die Musik” and many audience members were also cried.

Reporting on Lehmann’s New York Farewell Recital, several journalists claimed that it was not a coincidence that she cried during the last line of Schubert’s hymn to music, assuming that it was planned. We can best defend Lehmann’s integrity with this audio recording of her pianist, Paul Ulanowsky, who quoted what she said to him as they exited the stage that evening.

“Often a sigh from your harp, a sweet, holy chord from you opened the heaven of better times, You sacred art, I thank you for this!”

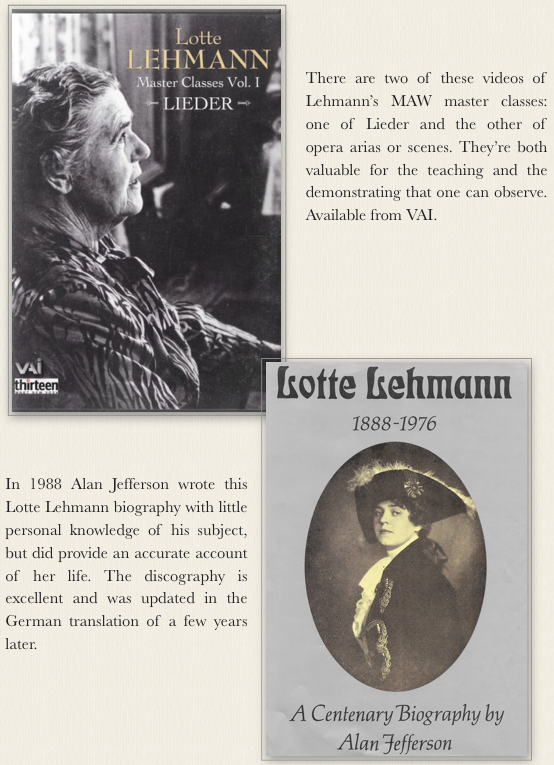

After her retirement as a singer, Lehmann had a successful new career as teacher. Her master classes were a revelation, a glimpse at the inner workings of an incomparably creative artistic imagination.

She never taught vocal technique as such, only interpretation. And Lehmann was gifted with the ability to articulate her vision in words. She inspired a generation of young singers to surpass themselves. Some of them who enjoyed worldwide careers included Marilyn Horne, Grace Bumbry, Benita Valente, Mildred Miller, and Jeannine Altmeyer. You may find more information about her teaching in the chapter called The Third Career.

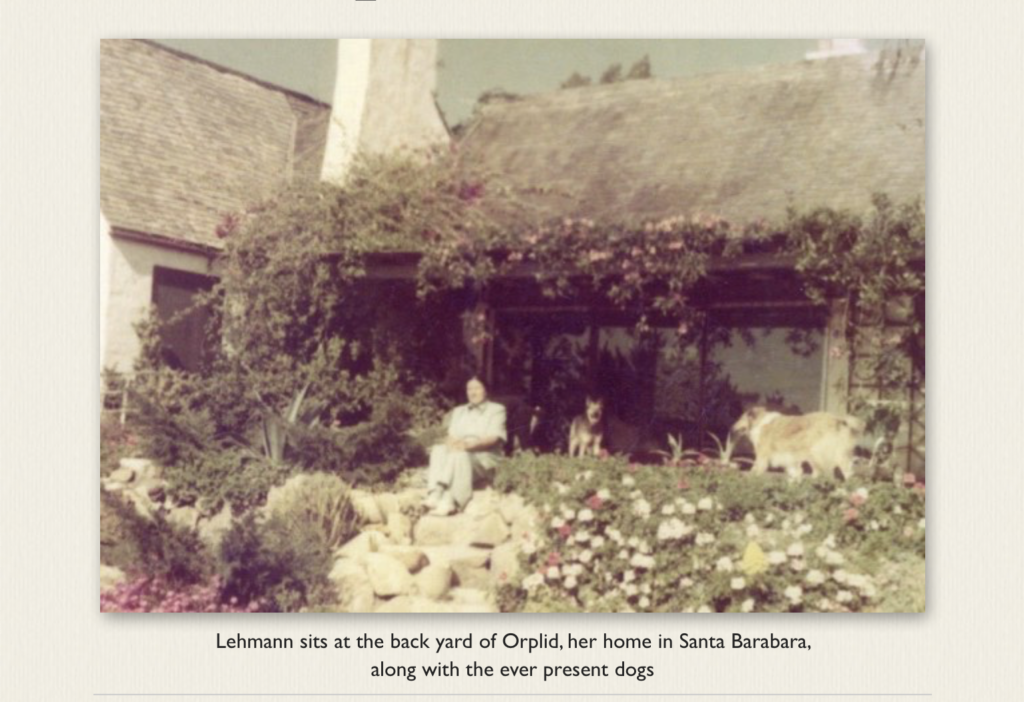

Lehmann had taught privately before, but it became more public when she took on the challenge of the vocal students at the Music Academy of the West which she had helped found in 1947. When she stopped teaching at the MAW in 1961, she accepted private pupils at her home in Santa Barbara, called Orplid, until her death there on 26 August 1976 at the age of 88.

In this YouTube video, Lehmann teaches and demonstrates “Sonntag,” a Lied by Brahms.

She had been honored by universities, interviewed in both German and English, and made the center of attention by her fans and friends right up until her death. Eventually, in Volumes VI and VII you can hear and see LL interviews.

In her last years she had returned to writing, educational, as well as poetic. She painted, did crafts, and traveled the world giving master classes.

Lehmann had always been a prolific writer. Among her eight published books is an autobiography, Anfang und Aufstieg, (literally, “the beginning and the upward climb.”) In Germany it appeared both in hard cover and what in 1937 passed for a paperback book. It was published in America as Midway in My Song. Lehmann’s More Than Singing has never been out of print, being for years available as a Dover paperback. It provides much detailed information on the interpretation of the Lieder she sang. Her My Many Lives discusses the psychological workings of the most important characters she embodied on stage. Her other books are listed in the Bibliography found in the Appendix.

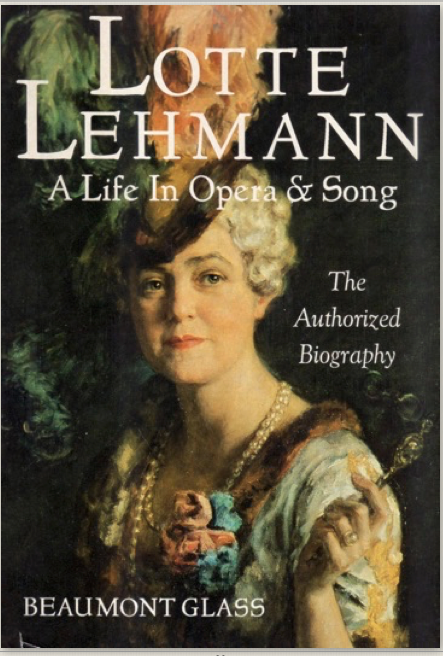

By 2018, six Lehmann biographies had been published. The hundreds of recordings Lehmann made, as well as the recorded radio broadcasts, were transferred first to LP and then to CD format. Her master classes were taped for public television and have been released as DVDs by VAI. In the author’s Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy Volumes III–V you’ll find her art song and opera master classes. Volumes VI and VII represent her interviews in English and German; Volume VIII demonstrates Lehmann’s wide variety of art; Volume IX, called Document, offers her suggestions on Lieder and opera interpretation, sometimes in her own handwriting.