Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy: Volume 2

• Lehmann was not Jewish; she left Austria in 1937 (before the Anschluss) because she’d already had trouble with Goering and knew what was coming. Also, her step-children were threatened, as they were considered Jewish in the eyes of the Nazis because of their Jewish mother. (Lehmann’s husband’s first wife was Jewish but he was not.)

• The controversy over her tale of meeting with Goering has been thoroughly analyzed by Dr. Kater in his Lehmann biography, Never Sang for Hitler: The Life and Times of Lotte Lehmann. Lehmann’s version was self-serving though colorful. You can find both versions in the chapter “Lehmann Meets Goering.”

• In matters private: as far as anyone knows, Lehmann was never sexually involved with the German conductor Bruno Walter (his mistress was soprano Delia Reinhardt), though Lehmann respected him as a mentor, conductor, and pianist. He accompanied Lehmann in recitals in Europe and the U.S. and in recordings, though he was not her regular pianist. Late in her life, Lehmann tried to explain what he meant to her on this rare tape from UCSB.

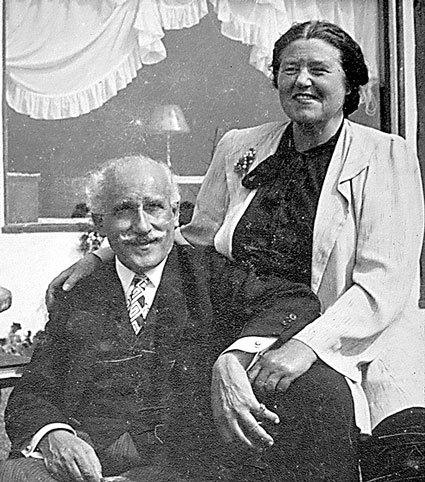

• Lehmann was intimate with Walter’s contemporary, Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini. See the chapter “Lehmann’s Conductors.” Late in their lives, the musical and the romantic (even sexual) mixed together; we have Toscanini’s love letters to prove it! (Re: letters, Lehmann wrote many. Her self-typed letters with her written corrections are particularly treasured. They seem just as spontaneous as she was.)

• Speculations in Lehmann’s personal life included rumors that she was intimately involved with women. No evidence of this has been found.

Frances Holden is reported to have had lesbian relationships when she was young. See the chapter “Frances Holden.”

Many people can’t imagine them living together platonically. I was with them both many times; there was the intimacy of a lifetime of companionship, but I witnessed nothing more. In her later years Lehmann seemed to enjoy the company of gay men and many of her students and close friends were gay men.

• Lehmann wasn’t Viennese. She was born in Prussia. After a short adjustment time at the Vienna Opera, she did better than “fit in” and soon seemed more “Viennese” than the Viennese.

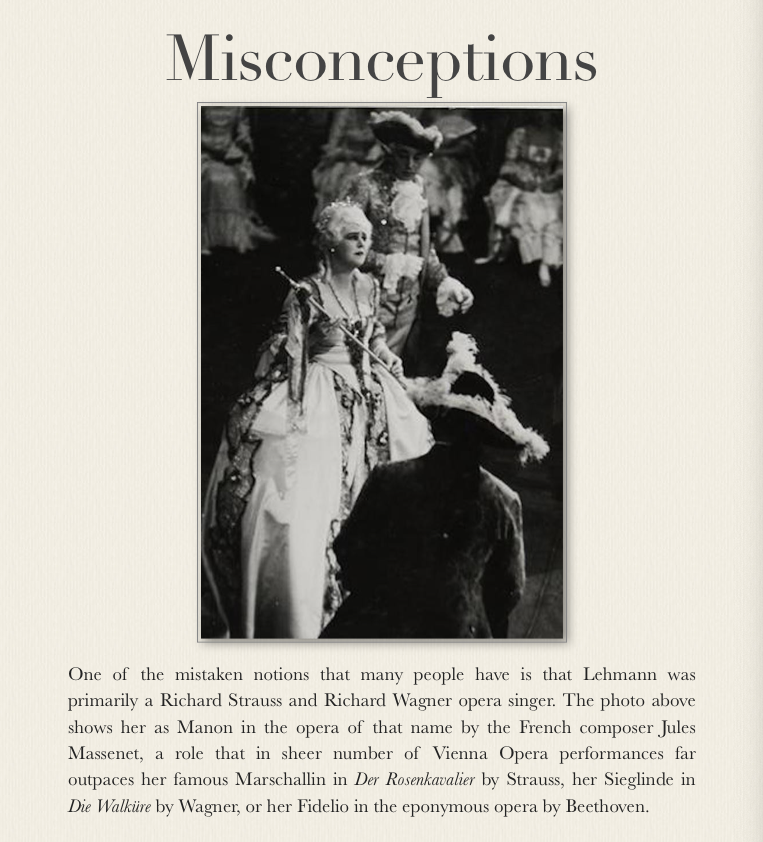

• As mentioned earlier, at the Vienna Opera Lehmann sang Massenet’s Manon more often than the Strauss and Wagner roles commonly associated with her name. She considered Fidelio one of her major accomplishments. Besides the Marschallin and Fidelio, Lehmann’s other favorite roles were Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, Elsa in Lohengrin, and Sieglinde in Die Walküre, all Wagner operas. She would say her favorite role was the one she was currently singing or studying.

• Writers sometimes complain that Lehmann didn’t sing the operas of her time, often citing the very successful Jonny spielt auf by Ernst Krenek, or Berg’s Wozzeck. And it is true that Lehmann wasn’t interested in jazz or atonal music. But she did perform in many world premieres of operas that every major opera company even today try out, hoping for a hit. Those flops included Julius Bittner’s Die Kohlhaymerin and Die Musikant, Wilhelm Kienzl’s Der Kuhreigen, and Walter Braunfel’s Don Gil. She performed in world or Vienna premieres of Pfitzner’s Palestrina, Korngold’s Der Ring des Polykrates and Das Wunder der Heliane, and Intermezzo by Strauss, which are seldom heard today. She did sing the successful early 20th-century operas such as Turandot, Der Rosenkavalier, Die Frau ohne Schatten, and Arabella.

• More sophisticated misconceptions include the assumption that Lehmann didn’t sing Lieder until she moved to America in 1937. Or that she gave up opera upon moving to the U.S. In reality, she had sung Lieder throughout her European opera career, but concentrated on this field in the United States, while at the same time singing opera until 1946 at major American opera houses. See “Chronology.”

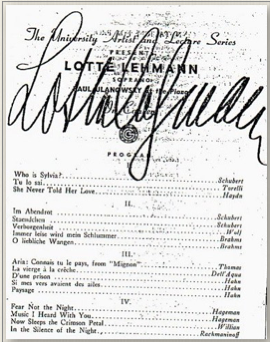

• During the Lehmann Centennial, a panel of people with Lehmann credentials spoke. Her pianist, Gwendolyn Koldofsky, was asked to comment on Lehmann’s apparent lack of breath control. She stated categorically and without apology that she felt that Lehmann just gave too much at the beginning of a phrase and was constantly running out. (As an aside, note how Lehmann signed her name: she almost always ran out of space and made the final letters small or curved to fit the page.)

For Lehmann, running short of breath came across as a great generosity of spirit, her voice flowing out without caring what would happen when her breath ran out. She often said that she made a virtue out of this “necessity” by infusing the quick intake of breath (in her own lifetime this became known as the “Lehmann catch breath”) with the intent of the poem, whether to show tragedy, wonder, love, or exaltation.

Critics complained that she broke phrases to catch a breath. Though this was true of her last years, her breath control was of average ability until she reached her mid-50s. In this 1941 recording of Beethoven’s “In questa tomba oscura,” she demonstrates excellent control of its demanding long phrases. A music historian wrote that lamenting Lehmann’s shortness of breath is like criticizing the Venus de Milo for not having arms.

• Another misconception is that she always had trouble singing high notes, but this can easily be dismissed by the 1925 recording in which Lehmann sings Butterfly’s entrance with a long-held alternate high D flat at the end. As with most sopranos she began to lose her top notes in middle-age, but it wasn’t noticeable because she cleverly chose her Lieder repertoire to avoid high notes and had already relinquished most of her opera roles that demanded the extreme high range.

• For a final comment on the subject of her vocal limitations, I’ll quote Bruce Burroughs, then editor of the Opera Quarterly from the Summer 1991 issue: “Lotte Lehmann—with a voice of utterly compelling emotive qualities before which a variety of technical shortcomings paled into insignificance…”

• Lehmann never sang at Bayreuth, nor did she ever sing the role of Brünnhilde. She never sang Isolde on stage, but did learn the role and sang and recorded the “Liebestod.”

• It’s sometimes written that Lotte Lehmann was a mezzo-soprano, and though she was able to sing with a healthy sound into the depths of a mezzo’s range, she was actually a lyric-soprano. She did successfully sing the dramatic Leonore in Fidelio and the demanding Turandot (not congenial to either her temperament or voice), but generally she stayed with the lighter soprano roles.

• Lehmann said that after her farewell recitals in 1951 she lost her voice completely. This wasn’t really true. The collaborative pianist, Dalton Baldwin, was present when Lehmann demonstrated a complete phrase of Wolf’s “Verborgenheit” for Gérard Souzay in full wonderful voice, years past her retirement. (See “Recorded Tributes.”) Frances Holden told me that she did keep her voice but it had just become limited with the passage of the years. As a result, after 1951 Lehmann didn’t feel comfortable singing in public (except in master classes an octave lower). In another example, a vocal music fan, Jack Lund, wrote that he was “at the Wigmore Hall [in the late 1950s] when Lotte gave her master class and Act I of Rosenkavalier and she sang out in full and glorious voice.” At the MAW during master classes she sometimes forgot herself and sang a phrase in the soprano range. We also have a recording from one of her master classes at Caltech when she demonstrated a phrase from Die Walküre in full voice. See “Third Career” Vol. I.

• There is another misconception that I’d like to address. It has been stated by various authors that Lehmann expected her students to copy her. She stated repeatedly that she wanted to open her students’ imaginations, but never wanted to see a lot of Lehmanns running around. Mme Lehmann was adamant on this, but I often wondered how a young person could avoid copying, when studying with such a famous teacher. Her students might at least try it out Lehmann’s way and then when they returned to their home, work out their own interpretation. Speaking as an instrumentalist, I can attest to wanting to copy my teacher (I was paying enough for the lessons!) and later found my own way. This occurs with most musicians. Here is what Lehmann wrote on this matter: “I do not want at all that you imitate me. I will listen to the way you develop a song and then make my suggestions. If you feel you must sing it entirely differently from the way I suggest, I hope you’ll tell me ‘I cannot feel it your way,’ and we will try to arrive at a way which will satisfy you and still convey the right feeling to the audience.”

• Sometimes Lehmann herself provided incorrect information, the result of her advancing years. She once stated flatly that she’d never recorded or performed with George Szell, yet we have her famous 1924 disc from Korngold’s opera Die tode Stadt, with Richard Tauber, tenor, as proof that she did! She also performed in Berlin opera houses under Szell’s baton. In the chapter “Rare & Well Done II” you can hear an aria from that opera also conducted by Szell.

• Another erroneous assumption is that Lehmann founded the Music Academy of the West. She was one of several founders, including Frances Holden, and did teach there from its beginning and helped shape its early history. The full story of Lehmann’s association with the MAW is told in the chapter “Music Academy of the West.”

Was Lehmann Always So Serious?

• The wealth of tributes to her work sometimes obscures Lehmann’s wit and lively personality. Here are excerpts from Dr. Herman Schornstein’s memories of Lehmann. “The second time I heard her was the following year, again with the San Francisco Symphony. I went back for her autograph. Getting [conductor] William Steinberg’s was easy. There was a long line waiting to see Madame Lehmann. She stood at a podium greeting fans. When my turn came, I blurted out, “Every time I hear you, I like you more.” I remember her withering response exactly: “Oh! You think I’m improving?”

Psychiatrist Schornstein also writes: “Lehmann enjoyed telling naughty stories—two I recall. One about two mental hospital patients both claiming to be Napoleon. To resolve their confusion, the wise psychiatrist had them spend the night together. It worked. The next morning one of them told the psychiatrist, ‘I lied. I am not Napoleon. I am Josephine.’ The other involved an elderly couple who decided they should have a baby. They went to their doctor who gave them instructions that worked. After the baby was delivered they were upset that it had red hair which no one in their families had. The doctor explained, ‘Rust!'”

“Before a Winterreise performance, I saw an exhibition of her twenty-four watercolors for the cycle at the Pasadena Art Institute. Another aspect of her creativity—’There was no art form that was safe from me.'”

Yet another Schornstein memory: “Lotte told me something about showing her passport at the Austria-Germany border and complaining to the guard about it displaying her date of birth. Whereupon, she said, he knocked an ink-bottle over on it. It probably was those blue eyes of hers.”

There are other misconceptions that also deal with the austere side of Lehmann. For some reason the fact that she performed and recorded operettas is forgotten: Die Fledermaus in Vienna and London; the Merry Wives of Windsor, Orpheus in the Underworld, Tiefland, in Vienna and Hamburg; and more. Again, just look at the early decades of the “Chronology.”

Another overlooked aspect of Lehmann’s discography is the fact that she recorded “pop” music. These were the waltzes and fox-trots of the day, and Lehmann still sang with the good diction and the same meaning of every word that she offered in arias and Lieder. Just listen to the style of these two light songs recorded between the wars.

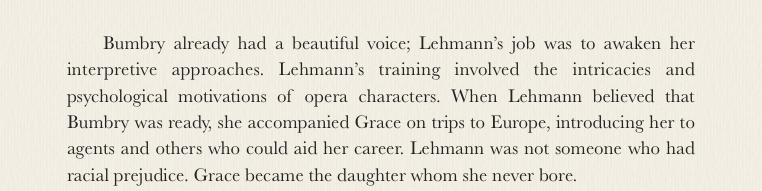

With “Jackie,” which is how her friends know Marilyn Horne, there were several situations in which Lehmann offended her. After Horne’s 1950s Santa Barbara recital, Lehmann, perhaps envious of all her gifts, may have been looking for something to criticize. She focused on “poor German diction,” which she condemned in front of a master class audience at the MAW. This wasn’t kind of her and Jackie found it hurtful. She often brought up the occasion during interviews, in her autobiographies, and in an Opera News article on Lotte Lehmann. In each case she misquoted Lehmann’s words. Even though I have sent Horne the exact transcription of the master class in question, she continues to use her incorrect memory. Here’s a recording of that actual master class.

On another occasion, Lehmann was supposed to have made a disparaging remark upon learning that Jackie was pregnant. (Lehmann often advised her female students against becoming mothers.) It was unkind and uncalled-for, but Lehmann sometimes did speak her mind without considering the consequences.

In spite of both of these issues, Jackie paid homage to Lehmann in writing, interviews, and tribute recitals. In her autobiography, she wrote: “Fair is fair, though. If I tell you of Lehmann’s dark side, then I must also tell you that she opened the doors of singing Lieder for me. Her instruction is inextricably woven into my own interpretations. As exponent and teacher, she was incomparable and inspirational.”

In an interview before her July 1990 recital in Santa Barbara, Horne said about Lehmann: “She had this unbelievable imagination and creativity within her…She really showed me what…a song can be. It’s a story within itself, from the first note of the piano to the last note of the piano. She showed me that a simple song, a small entity, has as much as a great huge scene or huge opera. It has a whole story to tell.”

One February I attended a Marilyn Horne recital in Carnegie Hall. When she finished her program she spoke to the audience and reminded them that today was Lehmann’s birthdate and then sang an encore in memory of her great teacher.

Authors looking to criticize elements of Lehmann’s life are able to find situations that illustrate her weaknesses—vanity, greed, or hypocrisy. Unfortunately, her enduring admirable qualities that don’t make for scandals are discounted or ignored.

I have been in touch over the years with many of her students, friends, and colleagues who consistently celebrate the positive aspects of Lehmann’s character: generosity of spirit and pocketbook; enthusiastic joy and support in students’ achievements; a constant P.R. department advertising her students’ successes in interviews and articles. There were lapses for sure, but Lehmann’s character was on the whole a positive, optimistic, celebratory one.