Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy: Volume 2

Benita Valente

On the long path to becoming a professional singer, I was fortunate to work with a number of exceptional musicians. My high school music teacher in Delano, California, Chester Hayden, was the first among them, and it was he who led me to the legendary German opera and Lieder singer Lotte Lehmann.

Lehmann, who had just retired from the stage and was heading the vocal program at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, accepted me for the nine-week summer session in 1953. Based on what she heard in our voices, she created an individual recital program for each singer whom she took on as a student. This was a special and unique gift, reflecting her largesse, and it proved to be of great value to me as I continued in my studies.

In all, I spent four summers at the Academy. After the second summer, I moved to Santa Barbara and, shortly after that, was accepted at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where I studied with baritone Martial Singher, but continued at the Academy for two more summers.

The schedule there was intense. From Monday through Thursday, we would prepare the repertoire that Lehmann had chosen for us for her master classes, working with soprano Tilly de Garmo on vocal technique and with her husband, conductor/coach Fritz Zweig, at the piano. They were among many gifted musicians who had fled Nazi Germany for the United States, and we were so fortunate to have the opportunity to learn from them.

On Friday and Saturday, Lehmann held two-hour master classes on interpretation, open to a paying audience and held in a large, elegant room of the Spanish-style mansion located on a cliff near the Pacific Ocean. Fridays were devoted to German and French art songs and Saturdays to operatic arias and scenes. The roughly eighteen students sat in the hall observing, and Lehmann (whom we always called “Madame Lehmann”) would call us to the stage individually, or as a group for opera scenes, to perform selections from the repertoire selected for study that week. Occasionally, when she heard a vocal problem, she would refer us to Tilly, and, during one summer, to tenor Armand Tokatyan.

The first Lied I sang for Lehmann in 1953 was Schumann’s “Die Lotosblume,” set to a poem by Heine. Because I had not heard German spoken or sung before, it took me two weeks to memorize the song, but there was a lotus pond down the road from the Academy that I used for inspiration. I also sang “Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht” by Brahms, which struck me deeply because my mother had died in 1954. Lehmann must have felt my strong connection with the music, for she was gentle with her critique.

In a professional career of over four decades, Lehmann had shown an amazing gift for taking on virtually any role or song and making it her own. She was always guided by the text, which she considered to be the key to expression and color. As her students, we reaped the benefits of this vast experience. We had to memorize each piece, and if we forgot the text Lehmann, puzzled, would say: “I would rather have forgotten the music than the words.”

Sometimes, when we just couldn’t achieve the results she wanted, Lehmann would step onto the stage to sing an aria or song, often an octave lower, that we were working on. On days when her allergies were not bothering her, she would sing it as written. Watching and listening to her, we were mesmerized by her ability to transform herself magically into another persona and overwhelmed by the depth and range of emotion she expressed.

She opened us up to the many possibilities of interpretation and made it clear that she did not want us to copy her, but to develop our own means of expression. By the end of each class, I had experienced such a range of emotions that I found I had developed a splitting headache and had to go back to my room to lie down.

Lehmann had sparkling blue eyes and wore elegant but simple ankle-length dresses, sometimes with a scarf of the same beautiful material. When each session was over she would sweep out of the room past the audience, surely aware of the impression she had made on us, her spellbound students. Yet she was, at the same time, a warm and friendly presence and took a personal interest in her students, being especially curious about our love life. “Haf you never been in love?” she would ask if we lacked the requisite romantic emotion in a song, and she would rhapsodize about moonlight, innocently translating the German word “Mondschein” into “moonshine.”

Learning how to act and move on stage was another aspect of our training. We were all somewhat awkward and needed to learn the basics. I remember being taught how to die in operatic fashion by our handsome acting coach, tenor Carl Zytowski, and one day Lehmann said to me in class, “Benita, I have heard that you have learned to die beautifully. Please die for us”—which I did! The acting lessons were valuable for our opera scenes and for the complete operas that were staged once a summer, though my skill in dying was not called for in the roles I was given: Barbarina in Le Nozze di Figaro, the Echo in Ariadne auf Naxos, and Adele in Die Fledermaus.

Another major influence at the Academy was Lehmann’s older brother, Fritz Lehmann, a highly regarded vocal coach who came to all the master classes and worked individually with some of us in his home in Santa Barbara, in the presence of his warm and loving wife, Theresa. Fritz shared my great love of Mozart and recognized that Mozart’s arias and songs were ideally suited to my voice. How right he was! Mozart became the cornerstone of my operatic career, with such roles as Pamina in Die Zauberflöte; Susanna, and later the Countess, in Le Nozze di Figaro, and Ilia in Idomeneo.

In addition to the summers at in Santa Barbara, I spent a winter there as part of a small group of singers working with Lehmann solely on Lieder. In this more intimate setting with students she knew well—at the end of each master class— Lehmann would sweep out of the room in her usual graceful fashion, pass us by and say: “Goodbye children.” Eventually I summoned up the courage to respond: “Goodbye, Mother.” One day there was an outsider in the room and I didn’t want to embarrass anyone, so I said nothing. Lehmann walked by me, looked at me, and, with a twinkle in her eye, silently mouthed the words “Goodbye, Mother.”

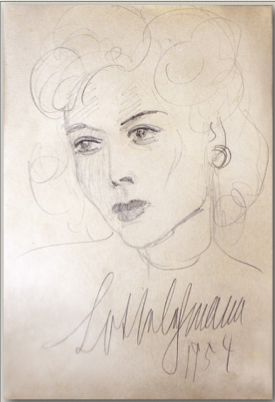

Lehmann’s immense curiosity drew her into many areas of life. She enjoyed creating art and did a painting for each song of Schubert’s song cycle, Winterreise. One of those paintings hangs in my studio. She loved gardening and made the tiles for the steps of her garden. She was a frequent letter writer, her handwriting large and sprawling and her words revealing her characteristic truthfulness and emotional openness.

Lehmann had a great love of animals. She owned two myna birds who could be heard from the garden imitating her speaking voice exactly. Once Lehmann asked soprano Shirley Sproule, who was my colleague and voice teacher at that time, to drive her to Los Angeles, and I happily went along, thrilled to be in her company. On our return we passed a schoolyard. Lehmann spotted a crow perched on the monkey bars. Although we assured her that the bird was fine, she later apparently worried that it was caught in the bars and insisted that her friend Frances Holden drive her back to the schoolyard. No bird remained—it was free!

In my current life as a teacher of voice, I think often of Lotte Lehmann, of her larger-than-life personality, her magnetism, her ability to become different people on stage. No wonder such major creators as Richard Strauss, who composed music for her, and Arturo Toscanini, who conducted her in performance, were so entranced by her! For me personally, one of Lehmann’s most important gifts was to open my path to loving the Lied and the song repertoire in general. Her equal commitment to opera and art songs has inspired me to follow the same path, adding chamber music, oratorio, and contemporary works to my own repertoire. I have accepted as key her principle that the words lead the way to the expression and color that the composer intended.

Lotte Lehmann, along with pianist Rudolf Serkin, who was a mentor to me at the Marlboro Music School and Festival in Vermont, and soprano Margaret Harshaw, with whom I studied from 1969 until 1995, two years before her death, were the musical greats who inspired me in my life in music. Passing on their artistic vision to future generations is both my responsibility and my privilege.

[I received the following email message from Ms. Valente in March 2016] …thanks for urging me to write this Foreword, for it caused me to bring back to mind so many wonderful memories that I have stored away all these years!

“[Here is a Lehmann master class at the MAW from the early 1950s in which Valente sang Schumann’s “Soldatenbraut.”]