Five LL Paintings (Auction)

The Auktionshaus Bad Homburg is offering five of Lotte Lehmann’s paintings in the next auction sale on Saturday, 28 March 2026. The company may be reached at aubaho.de or auktionshaus-bad-homburg.de

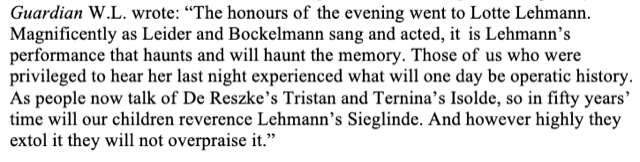

Reviews from Vienna Newspapers

We have discovered some reviews from the 1930s that treat Lehmann very well!

“Lotte Lehmann gave a song recital with Bruno Walter. Much has been said in abundance regarding the vocal artistry, performance, inner discipline, and spiritual content of the presentations. However, Lotte Lehmann possesses qualities beyond that which seem to be unique—just as unique as the tear that trembled in Richard Mayr’s voice. With Lotte Lehmann, it is the interplay of spiritual shades, shifting from the cheerful to the pensive, from the pensive to the melancholy, and from the melancholy to the dramatic. Even in her cheerfulness, a tone vibrates that sounds a bit in a minor key. This soft minor tinting transitions into a Beethoven-esque drama. It is feminine, yet heroic drama. Somehow, Leonore is always there. The meditative and the impulsive are united in Lotte Lehmann with rare perfection. Thus, this voice once again became a great shaper [of art]. The program included Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Hugo Wolf and…”

“Events of world-class stature are overcrowded in Vienna even today. What Lotte Lehmann means as a lieder singer is understood here perhaps better than anywhere else, because we have followed the beginnings of such artistry, recognizing its growing maturity.

To truly grasp songs, as this woman does, requires—aside from all musical and vocal perfection,—a human greatness and, at the same time, a tenderness that can only be wrung from a life in the wide world, a life lived with the soul. That is why it is such a unique performance we are witnessing with Lotte Lehmann now—a performance that reveals all the wonders of (let us call it) romantic Germanness. [the critic is a Jew, so there’s no Deutschland über alles in his words]

Schumann, Brahms, Richard Strauss, poets from Heine to Dehmel: this is a spiritual province that, thanks to such a singer and interpreter, is now opening to the whole world, finding the most beautiful understanding everywhere. Let us not even begin to speak of Schubert, who gave his sounding voice to all of old Austria.

The course of the evening: ovations, repetitions, encores, and a farewell that was delayed again and again. It was never more beautiful. But half of such happiness came from Bruno Walter. In his piano playing, the ideal of the German Lied is reflected: symphonic texture around a melody (Symphonik um ein Melos).”

LL Film Planned

This recently discovered newspaper article from 1935 offers the “What IF?” question to the past.

Gerron to direct Lotte Lehmann film

Lotte Lehmann is now also set to star in a film. She will portray a great singer who must grapple with the conflict between her career and her private life. She tries to renounce her art to save her marriage and family happiness. However, she doesn’t quite succeed, and ultimately returns to her art. Kurt Gerron will direct the film. Negotiations with Ms. Lehmann are expected to be finalized in the coming days, with only financial details remaining to be settled. Filming is scheduled to begin in September. 1935

LL’s Students Obituaries

We have finally completed the page that offers obituaries of all of Lehmann’s Music Academy of the West students (the students we know of). Often you’ll find the student’s recorded memories of working with Lehmann. For some of the lesser known students we have included some recordings of their work.

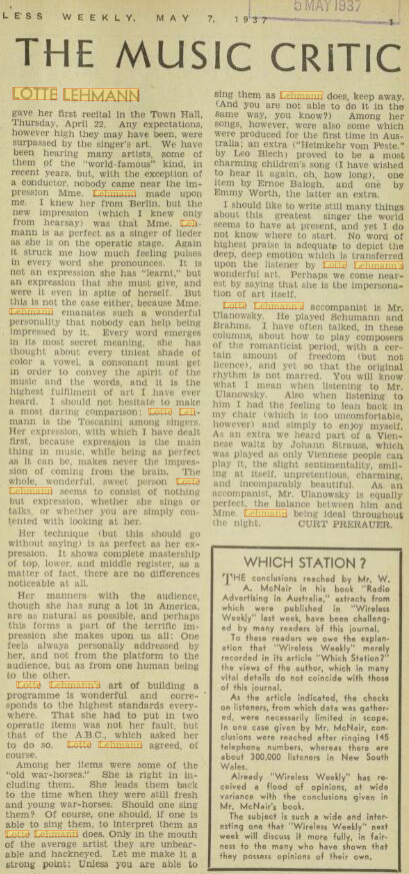

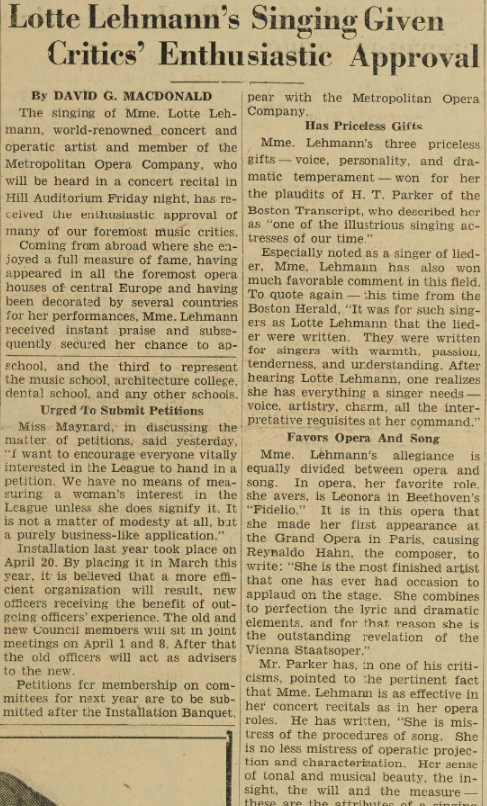

Town Hall, Australia

1935 Review

John Amis on Lotte Lehmann

In 2021 John Amis put together a program of Lehmann’s singing called Lotte Lehmann: Vintage Years which can be found on YouTube.

LL at the New Met

We have a short (interrupted) interview with Mme Lehmann (preceded by the First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson).

La Scala?

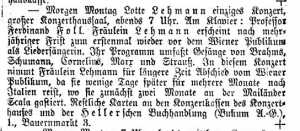

• You can’t believe everything you read. This appeared in the Neue Freie Presse of 20 January 1924. In English: Tomorrow (Monday) Lotte Lehmann‘s single concert [we’d call it a recital] at 7pm. At the piano: Professor Ferdinand Foll. Miss Lehmann appears as Lieder singer before the Vienna public for the first time in several years. Her program contains songs of Brahms, Schumann, Cornelius, Marx, and Strauss. In this concert, Miss Lehmann takes leave of the Vienna public for a longer period of time, because only a few days later she travels to Italy for several months, where she first appears as a guest singer for two months at La Scala, Milan. Remaining tickets…..The recital information is correct, but Lehmann didn’t sing on those dates at Italy’s La Scala. Rather, in this case, she traveled to Berlin, first to record on 13 February and then to sing opera there with Georg Szell, among other conductors at the Berlin Staatsoper, where she remained, making records and singing opera until 21 May 1924 the date she sang her first Marschallin in London under Bruno Walter’s direction. She continued singing opera (Ariadne auf Naxos, Der Rosenkavalier and Die Walküre), not returning to Vienna until the next season when on 9 September 1924 she sang in Faust. As usual, many thanks to Peter Clausen for the clipping. P.S. Lehmann did eventually sing a recital at La Scala, but in 1935.