It is with joy that I offer the accounts that the following Lehmann fans, friends, students, and colleagues have written. I thank them all for their contributions to her memory.

• The great British operatic-comedian, Anna Russell (1911–2006), recalled:

Once, just after my first record came out, I was staying with this friend of mine in Los Angeles who was a very good baritone, but an amateur singer. One afternoon he said, “Anna, my dear, I shall have to leave you on Tuesday when I go up to Santa Barbara for Lotte Lehmann’s master class.”

When I was a student at the Royal Academy of Music, I would have done anything to hear Lotte Lehmann. I would have spent my last dime! So I said to him, “You rotten, miserable, amateur funeral parlor baritone, you make me so mad! Here I’ve been Lotte’s fan for a thousand years and you get to go to her master class. I’m so furious with you.”

My host wasted no time in telephoning Lehmann (who was a personal friend) and asked if he could invite his house guest to sit in on the master class. “Is that Miss ‘Schlumpf ist mein Gesetzenbaum’ Russell?” inquired the legendary diva.

I thought, “Oh, God, how marvelous, Wow! Lotte has heard my record.” So we went up there and I was sitting in the back of the room wrapped up in all this teaching of lovely Lieder when, all of a sudden, Lotte said, “And now, Miss Russell, we shall interpret ‘Schlumpf ist mein Gesetzenbaum.’”

Lotte and Gwen Koldofsky had worked out the accompaniment off of my record, so she told the people in the room that for those who didn’t understand German, it means “Dumb Is My Sitting Tree.” Then she got me up in front of the class. Everyone started to shriek and giggle until Lotte said, “I don’t want any laughing.”

She went through all the phrasing and picked it to pieces. It was the funniest thing because everyone was trying so hard not to laugh that they were almost dying. We became great friends and she later presented me to Santa Barbara society. I also established a scholarship in my name for her master class at the Music Academy of the West. The first person to have my scholarship was Grace Bumbry!

For Lehmann’s 75th birthday celebration, Marcia Davenport wrote:

When in these lines about the incomparable and unforgettable Lotte Lehmann I refer to her as Lotte, I am not using careless contemporary argot; I am writing about one of my oldest and dearest friends. I first heard Lotte sing in 1930 at the Staatsoper in Vienna. She was at the height of her powers as an opera singer, and she remained at that height for the ensuing decade. Thereafter she turned to lieder, singing recitals, which, like her interpretations of Fidelio, the Marschallin and Sieglinde, have become the standard by which her successors have been measured and found wanting. It would be neither realistic nor a tribute to Lotte for a friend and critic like me to claim that she was peerless in all music. She was not.…

Lotte was born with the voice, the heart and the histrionic genius to become one of the true immortals in the history of singing.…Lotte’s Fidelio…was the inspiration and the model for my fictitious one in the novel Of Lena Geyer, whose protagonist is a composite of the best and greatest I ever heard or knew of in the whole art of singing.

“Lotte Lehmann Remembered” by John Coveney, Director of Artist Relations for Angel Records, written for her memorial service at the Music Academy of the West.

…Tentativeness, curiosity and apprehension were in her movements even before she sang Sieglinde’s questioning first lines and then…I heard the perfect annunciation charged with quiet emotion, the concern with text and meaning, that were hallmarks of a Lehmann performance, approached by few and exceeded by none.…as Richard Capell was…to write in Grove’s Dictionary, “Along with her rich vocal gift went a rare theatric power of establishing herself from the first phrase of a part as ardently engaged and quiveringly sentient.”

…Every nuance of Sieglinde’s character was implicit in her beautiful voice, and explicit in her appearance and actions; her musical and dramatic instincts, unerring.

…All during her career she had exerted a rigid self discipline which made her recognize her own limits. Her inherent honesty made her relinquish role after role when she felt they no longer suited her, or she could no longer do them justice.

…I suspect she died with two regrets, that she never sang Leonore in this country [USA] and that she never sang, or could sing Isolde anywhere. She often spoke about the latter with a sense of aspiration, as though to her it was the ultimate operatic achievement.

…A really great performer stands side by side with the composer in the creative crucible as an instrument of revelation, and we are enthralled in such a way that all mundane considerations disappear for a while like ashes in the wind and we are in the presence of something beyond our understanding. Lotte Lehmann was such an artist and for that I and countless others…are grateful.

Max de Schauense, Music Editor, Philadelphia’s Evening and Sunday Bulletin, wrote the following for the LP release of Lehmann’s Brahms and Wolf songs.

Lotte Lehmann occupied an altogether special niche in the world of opera and song. As always happens with distinctive, individual artists, she has never been replaced as far as those who heard her are concerned.

…I have often thought that the inner core, the magnetism of Lehmann’s art and personality stemmed from the fact that she never lost the breathless wonder of childhood. No matter how mature or adult a task she undertook, through it all shone that quality of a child filled with awe of the natural world, of the first stirrings of love. Hers was always a nostalgic, art–wondrously served by her role of the Marschallin…and even more miraculously by her singing of lieder.

Like many great singers, Lehmann has been the subject of frequent analysis as to the caliber of her voice. When I first listened to her in 1927 at Munich, singing Sieglinde and Eva, I thought hers one of the most beautiful voices I had ever heard. It shimmered and soared at the service of a burning, imaginative temperament.

Critic Alec Robertson wrote:

She played on her voice, one might say, as Kreisler (also with a golden tone) played on his violin. A singer however, must do more than that. Words must be mated with tones; they must be given their proper color and significance, fitting the dramatic or emotion situation; underlined, but never overstressed. In these matters Lehmann, with her exemplary enunciation, excelled…all she did was controlled by fine musicianship and strong artistic discipline.

For an article he wrote for the Los Angeles Times in 1976, Martin Bernheimer explained:

…We are lucky. With Bruno Walter as her inspiring enactor and Lauritz Melchior as her heroic partner, Lehmann’s radiant, urgent, womanly performance [in her recording of Sieglinde] remains as compelling today as it must have been…decades ago. If she had done nothing else in her career, this sonic document would easily have assured her place in history.

Lehmann’s unique art sprang from her heart, her brain, her voice and her technique, probably in that order. Technique came last.

Her tone production could be uneven, her phrasing hampered by limitations of breath control. Her top was precarious…. With lesser singers such problems could be fatal. With Lehmann they were at worst, passing blemishes.

…Let it not be said that Lotte Lehmann lacked ego. She was, after all, a prima donna. The real thing.

• Ted Mignone wrote “Memories of Lotte Lehmann Recitals at Town Hall 1947 to 1951.”

In 1947 I was 16, quite new to opera and unaware of lieder. When a few of the regular Metropolitan Opera standees asked me to go to a Lotte Lehmann lieder recital I agreed without realizing what was in store for me. I will never forget the impact of the first time. The feeling in the house was different from the Met performances. It seemed that every one wanted to be there. There were many people who knew each other so there were many greetings exchanged from middle-age and older Germans, teachers and students, Met opera standees, single men, and musical celebrities. The anticipation buzz was high. When Lehmann walked on stage the applause was not only wonderfully loud but sustained. I looked around at the smiling faces looking up at a dear friend. I myself thought that she was my favorite Aunt (a lovely warm woman).

The smile was infectious but it’s the watery bright blue eyes which affected me most—all the way up from the rear balcony. Such a feeling of intimacy and friendliness. As she waited for Paul Ulanowsky to sit and arrange the music, she turned to the audience and smiled again—every one smiled back and laughed with her. By the time she began the first song I was her friend and she mine. I remember that impression not only because it was the first time I’d experienced something like this but also from my discussion of the event with my parents afterwards. When I told them that Lehmann “sang to me,” my father said, “Al Jolson had the same effect on an audience.” I understood that remark later in life when I saw some popular entertainers who were able to touch an audience in a personal way. Throughout the years I’ve seen many wonderful lieder recitals from Schwarzkopf to today’s Hilmar [Thate?] They held your interest with Lehmann’s qualities of musicianship, tone of voice and communication of the text BUT none did it personally as if they were next to me singing it simply and to me. I know that this has been said by many people but I didn’t know that then and after 55 years I still feel the same way when I think of her and when I listen to her recordings.

• In a letter to me of 10 May 2002, soprano Dorothy Warenskjold (1921–2010) wrote:

I didn’t study with Lehmann—at least, not formally. By that I mean that all her recitals were a kind of learning experience for me. She was one of only two singers that ever sent me out of the auditorium walking on air. I will never forget her farewell Town Hall recital…Early in my career, I was planning to go to New York to try for national management [and a mutual friend asked] if Lehmann would be willing to write a note recommending me to her manager, Marks Levine….(She had seen me do a recital in Santa Barbara…) At her request I came down from San Francisco to visit her in her home [in Santa Barbara]. I was fully prepared to sing for her but she assured me it wasn’t necessary. She had heard me recently, she said, on the Standard Hour Radio Program. We had a delightful few hours together. And as I left she said she would be happy to contact Levine. A few weeks later, in New York, I had an appointment with Marks Levine….Well, I sang for him with the result that I was taken under contract….I was always very grateful to Lehmann for her kindness to me in those early days of my career….A few years later she came backstage to see me…after my first Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier.

• Sherman Zelinsky wrote in a letter of 24 May 2002:

I had but two visits with Lehmann…the first at the Orrington [Hotel] in May 1967 after her last master class at Northwestern—the morning she was leaving for Europe. She really didn’t then discuss politics—though she did relate her Göring-lion story, adding just a few comments. My second visit with her was at Orplid at her open house for her 80th birthday….The bulk of my friendship with her was the correspondence we had with each other from 1967 until her death in 1976. [Mr. Zelinsky then tells of the Goethe Bicentennial year of 1949 when Lehmann came to San Francisco to sing an all-Goethe program.] After singing the printed program there was quite thunderous applause requesting an encore. After coming to the platform several times, she finally held up her hands to quiet the audience and announced in a rather sheepish tone of voice….‘I don’t know any more Goethe songs! So may I sing one of these over again?’ I believe it was the Schumann ‘Talismane.’ There was more applause; then with a smile on her face and a twinkle in her eye, she said something to the effect that, ‘It isn’t Goethe, but maybe you will let me sing for you “An die Musik”’—and sang it as never I’d heard her sing it before.

• In July 2002 Bruce Herman wrote:

When I was in my twenties in the Sixties, I went to see a film version of Der Rosenkavalier with Elizabeth Schwartzkopf and loved the opera. I had heard only that Lotte Lehmann was a famous Marschallin. I knew nothing of her, but borrowed a set of records from the library. Very poor quality and mono, of course. I can’t explain the next part. The only other one it worked with for me was Caruso. I felt that Lehmann was right there in the room with me as I listened. Even through the really poor sound reproduction she reached me. I have been fitfully fascinated with her ever since.

• Ron Murdock wrote the following:

Mme Lehmann gave a two master class at Mount Allison University which is located in Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada. I’m not sure now just how they managed to persuade her to come. The University is an excellent one but, just the same, not exactly located in Montreal or Toronto! I do remember she was en route to Europe. The master classes took place in January or February of 1962 if I remember correctly. I sang Schumann’s “Widmung.” What is vivid, still, in my memory is how she coached a young soprano on the role of the Marschallin. It was spellbinding to see. Mme Lehmann was suffering from a heavy cold and had almost no voice because of it, yet when she demonstrated the intensity of the scene one quite forgot there was actually no voice coming out!

• Professor Carleton Elliott, now retired, spoke about the above event as follows:

It was organized by a wealthy pianist from Montreal named Eallin Ballin who was a friend of Lehmann. Bob Tweedy made the travel arrangements and the singers came from many places, bringing their own pianists. Lehmann worked with the pianists as well as the singers. I remember one song in particular. It was Schubert’s “Die Forelle” and the singer was told not to be too emotional about the story, because it dealt only with a little fish. During the event Lehmann bid us remember the name of her then student, Grace Bumbry, who she said would make her mark. Sadly the master class was not recorded.

• André Tubeuf wrote the following remembrance in 2016:

• André Tubeuf wrote the following remembrance in 2016:

I had been exchanging letters with Lotte Lehmann for several years already, every second or third month, without any hope or even idea of meeting her some day. I knew she travelled every late spring from California to Bad Gastein for a cure; and enjoyed attending in Vienna some celebration or a performance in Salzburg during the festival. In 1970 she had to be there. One “Lotte Lehmann Promenade” would be opened in the heights of Salzburg, of course she would attend, and enjoy. And she would stay another few days for the new production of Ariadne auf Naxos. Remembrances there would be, and plenty. She had had the first break in her young career with the second, Viennese version of Ariadne where she created the part of the Composer, a sensational start. Then Strauss himself begged her to leave this boyish part, as he wanted her as Ariadne for Salzburg; the first attempt to bring there a modern opera along with Mozart’s ones.

She would stay at Fondachhof, a charming hotel up in the hills, with a beautiful garden. Would I perhaps try to come? Strasbourg (where I lived) should not be so far away…

And why not? We had just moved to a larger flat, I had spent most of July scrubbing floors and cleaning walls, we quite deserved this short leave. Finding seats for Ariadne and Christa Ludwig’s Liederabend would be easy no doubt, for Rosenkavalier (Karajan/ Schwarzkopf/ Jurinac, yes) that would be harder. Thus we went, spending the whole next day finding seats (that was still possible at that time, but for Rosenkavalier we would have to share two seats between the three of us) and last but not least, enjoying the beautiful Wolf evening with Christa Ludwig at the Mozarteum.

The appointment was for 11am on 1 August. I had called Madame at her hotel just to check if it still worked, thrilled to hear the deep, strong voice, its somehow raucous quality amplified by the apparatus. Of this voice I knew as much as was possible through the records. Even the spoken voice. I had spent time learning my best German from the incredible enunciation of her reading of Rilke’s Cornett on LP. Warmth was the first virtue you noticed in her reading. On the phone it seemed so distant, cold. Would I really dare climb up to Fondachhof? And to say what? I feared…

Of course I went. On time. And of course she was already in the garden, in a large armchair, quite dressed up, silk and soft colors, her face lightly burnt by sun and open air (she had earlier had her cure in the heights, at Bad Gastein), all smile and welcome. And warmth. How tiring had it been having to drive so far? How was my wife? The children? Her sole concern was real today life, we could have been lifelong friends, joining again after many years separation. She had coffee and some Viennese pastry ready on a small table next to her, offered (and sipped herself) some coffee and asked if I had attended Ariadne? Not Ariadne, not yet. Next performance would be only on the 2nd. But the Ludwig recital. “Oh it must have been vonderful (her whole life she must have never been able to drop her German v for the English w), she is a very great singer. But I did not like her Ariadne at all. Ariadne should soar. Strauss parts should always (alvays) soar.” Then she sent a big warm smile to two poodles a fair elegant lady on heels who was walking them on the grass. But the lady did not get such a smile, though she was quite obviously looking for one. It was Hilde Güden, staying at Fondachhof. [She later coached with Lehmann.] At the same moment a window opened at second floor in front of us. That was Jurinac’s, whose head appeared just a little in the fresh midday air. Lehmann raised her head, some very special warmth came to her eyes. “Oh this one is vonderful. She only is the way we were, in our time. Direct. Free of the sophistications of to day….” Of course Jurinac had sung the Composer in the Ariadne performance, the part Lehmann had adored, hating to have to leave it. When she turned to Ariadne, she never resisted staying in the wings to watch the Composer pour out (soaring!!) the beautiful hymn to Music.

So we talked, a whole hour. She had brought the brand new LP reissue of her Schöne Müllerin on the cover of which she inscribed the most charming words. I could feel I was welcome. That was the first step. The following year I had to go to Vienna in June for the exams at the French school. A pleasing task, since from Vienna the train to Bad Gastein was an easy trip and there the whole weekend I was her guest. There she would live in the central front suite which had been Toscanini’s favorite, and the whole staff (and mere hotel guests) would treat her as royalty. A lady from former times, with a smile and a warmth and kindness of her own.

• From Syracuse, New York, Jane Birkhead wrote:

Having heard Lotte Lehmann sing, having had her as a friend, having coached Lieder and opera with her and her brother Fritz Lehmann for many years, [all this] taught me not only the art of singing but also the art of living.

• Hermann Schornstein’s other contributions to this book can be found earlier in this chapter as well as in “Misconceptions.” Here are some of his very personal memories and letters from Lehmann and Holden:

From 1945

During the last year of high school, I began ushering at the San Francisco War Memorial Opera House. That, plus flying to Los Angeles for one performance, was how I heard her last Rosenkavaliers.

I went to a Rosenkavalier rehearsal with great expectations, but was terribly disappointed; Lehmann no longer did rehearsals. Before the performance, I waited at the stage door to get her signature in Opera magazine—an article about the 1945 season featured pictures of the principal singers. She walked up alone. I didn’t recognize her at first—a slightly dumpy, middle-aged woman, walking slowly, snug in a fur coat. Not the glamorous persona she could invoke on demand. Many of the singers I’d approached asked my name and signed “To Herman.” Because she was special, I wanted to make sure and asked, “Would you write ‘to Herman’?” Without hesitating, she took the magazine, said, “No!” and signed. This was before a performance and I should have realized she must have been stressed and tense and didn’t welcome this attention.

The next month was a recital. The War Memorial was not filled; the audience mostly older and treated like family. I wrote in the program that before her last encore she said, “Sit down!”

From 1947

In the spring, as part of the Beverly Hills Music Festival, Franz Waxman conducted a program which included excerpts from Act I, Rosenkavalier. In December at UCLA another recital, in which she sang the Brahms Zigeunerlieder—wild and wonderful. I bought the album immediately—and have not yet heard a performance or recording that approaches hers. She did that with lots of music. Later I told her how very much I liked those particular songs. She seemed surprised: “You do?” Apparently she didn’t. But you wouldn’t have known it listening.

Alexander Koirensky came to visit his old friend Mme Ouspenskaya. He had been an assistant to Stanislavsky at the Moscow Art Theatre and was a translator of Chekhov. I told him I was going to a Lehmann recital. First he said how lucky I was. Then he paused in a way many Russians pause as they remember the past, and added, “When she sang ‘Doppelgänger’ you didn’t just hear it — you felt it here,” indicating his gut.

From 1949

Before a Winterreise performance, I saw an exhibition of her twenty-four watercolors for the cycle at the Pasadena Art Institute. Another aspect of her creativity—“There was no art form that was safe from me.” This is how we were to connect fifteen years later. She’d had painting lessons with Charlotte Berend-Corinth (1880–1967), the widow of Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), and was a respected painter in her own right. I didn’t go back after the recital. As I passed the green room, her old friend and colleague, Tilly de Garmo (1888–1990), was walking in. Lehmann was delighted to see her: “Tilly! When you didn’t come back at intermission I thought you didn’t like me!”

From 1964

Remembering the Winterreise watercolors, in June I wrote a letter about my interest in purchasing one of her paintings. It was forwarded to Austria. A postcard came from Bad Gastein: “Please remind me after August. I then will be home again!”

I did as told and received a disappointing response:

Santa Barbara—September 17th 1964:

“I am sorry—but it seems to me quite impossible just to chose a painting and asking a price…I don’t know what you like, I don’t know what to ask…I feel flattered, but rather helpless. Forgive me for not fulfilling your request!”

I immediately wrote back recounting memories of recitals, especially her performance of “Morgen,” at the first recital, and of painters I admired.

Her reply September 22nd 1964:

“You gave me an idea: I painted once a watercolor (which I dearly love and certainly never would part with!) of an island in the Baltic Sea where I—as a young woman—spent many summer vacations: Hiddensee. I shall—try to paint an oil painting, taking this beloved spot as a ‘guide,’ changing it a little bit, so that it fits the ‘Morgen.’ If I suppose that it seems all right, I sell it to you…Is 250$ too much? At least it is painted especially for you!”

All right! On October 1st:

“Thank you for your letter. The picture is painted—and I hope you may like it. It will take quite a time to dry because it is painted with a knife and the color lies very thickly on the canvas. I believe that I have caught the serenity of ‘Morgen.’ I shall write you when I have mailed this picture to you and I shall be terribly anxious to hear if you like it or not. If not—then please send it back—and I mean that!”

Three days later:

“I have a terrible problem: two painting experts saw yesterday the painting of ‘Morgen’ and did not think it very good. But some Zijutias (I don’t know how to spell the name of this flower) [Zinnias] which I have painted really excited them and they said that I should send this flower painting. It will—by the way—take weeks till the pictures will be dry—and I shall be….at Northwestern University….and home again November 15th—so you have time to think it over! There is one solution: I could send both for approval and you send back the one you don’t like. How is that?”

From Chicago:

“That really is too bad that I shall not meet you in Chicago! To have an admirer of my paintings is much more exciting than one of my singing (in the past!)… I painted a third picture for your choice: a beach, much sunshine and two figures in the foreground. A little too obvious perhaps? But it certainly is an illustration to ‘Morgen.’ So you have three to choose from and I do hope that one will please you. Otherwise send them all back!”

November 16th:

“I came home the other day from Kansas City and found the three paintings dry and all right. I will send them today or tomorrow. Please be quite honest: if you don’t like any of them, send them all three back and I assure you that you don’t hurt my feelings. I want you to LIKE the picture you so graciously buy and not have the impression that out of politeness you should keep one if you don’t like it. If you find one to your liking, send please the others back. I am sorry to trouble you with packing them and mailing them, but I really think that this is the best way to get a picture which you may hang on your walls.”

They arrived—we eliminated one—but choosing between the Zinnias and the second “Morgen” was not easy. I asked if we could keep the two for a couple of weeks before deciding.

November 29th:

“Thank you for your check. I am so very, very happy that you like even two of the pictures. To make the choice for you easy: I give you the second one as a present. Please take it! Warmest regards….”

From 1965

She was to be in New York for a Master Class at Town Hall in April. I wrote we’d be there.

“Of course I have to meet you and Mrs. Schornstein! I am so glad that you will attend the Class. Could you come to the Artist Room after the class? It will be the only possibility to see you. You can imagine how these few days will be filled with one appointment after another. I have so many friends in New York and am so seldom there. I shall be at the Savoy Plaza (or is it now called the Hilton Hotel?) and PERHAPS I shall find a minute, please call me in any case!”

After being introduced by John Brownlee (1900–1969), she came on stage and the audience went wild. When she was able to get us to stop applauding she said, “Like Hans Sachs says in Meistersinger, ‘This is easy for you, but it is hard for me.’” Afterwards it seemed the entire audience went back as they had at her farewell in that auditorium fourteen years before. At the doorway of the Artists Room she sat protected behind a table. We introduced ourselves—she smiled, nodded, and we were pushed on and out. When we got to the street, I realized, “She didn’t know who we were.” It was the only time I saw her totally overwhelmed by an occasion.

Disappointed, I called the next morning. She invited us to her room where we spent a half-hour or so. To my surprise, she had flown to New York alone. Because of their menagerie, she and Frances were no longer able to be away at the same time. Lehmann said she was returning to New York next April as a guest at the closing of the old Met. “Will you be traveling alone again?” “Oh, yes.” This wasn’t my image of how great artists traveled. I said something about my concern (she didn’t seem to have any) about the dangers of travel and New York City and that we had better come to California and fly with her. She thought that would be fine.

From 1966

We arrived at her home, rang the bell, she opened the door. She introduced us to Dr. Holden and then took us on a brisk walking-tour. First through the house. She and Frances each had their own large living rooms: music room and library. In this way Lehmann could isolate herself from Frances’ friends whom she found “too dilettantish.” There were many watercolors and felt appliqués on the walls—including the two song cycles—without any consideration given for their conservation. Many of the watercolors were faded, the exposed cloth pieces faded and moth eaten. As we passed through a hallway to the garden, in a protected spot, I recognized a pristine watercolor of Detroit: a snowy day with the Fox Theater marquee in the background. Painted before a Detroit concert. Passing it, Lehmann said in an aside, “You can’t have that one.” I hadn’t asked. She knew before I did that I would want it. We followed her to the garden, the walk-in birdcage, and two kilns. Frances had to get the second; Lehmann couldn’t stand the time it took for ceramic pieces to fire and cool. In the garden was an uncanny life-like statue of Lehmann singing.

It stood just off the path to the home’s most often used entrance, the good friend’s entrance. You’d catch a glimpse of it in your peripheral vision and feel for an instant there was someone there and then that she was standing there. Frances intended that this remarkable piece go to the University of California’s Lehmann Archive where I felt few would see it. Although none of my business, I suggested that the Music Academy seemed a more appropriate repository. Especially since so many current vocal students stood as though nailed to the spot with arms lifeless at their sides. Lehmann’s approach and practice was that singing goes from “the top of one’s head to the tips of one’s toes.” And to sing “with a forte of emotion”—which doesn’t mean loud.

Back to the first tour of Orplid. In the studio where she did some of her artwork—glass mosaics, ceramics, tiles, and sculpture, she pointed to a box of works etched with a stylus on a special black board. She said pick one! I picked a very sweet angel who appeared to be giving a vulgar hand gesture. Lehmann found hands to be the most difficult part of drawing. I have a Madonna and Child in which the Madonna has two right hands.

Later two friends arrived. Frances served hors d’oeuvres and drinks. Lehmann mentioned that she was quite tired and wasn’t at all looking forward to the trip. Now being more aware of her history, I asked why then was she bothering to go, as the Met hadn’t been that major in her career. I thought the other people would kill me. She didn’t disagree, but said she had promised.

The next morning Frances brought her to the Biltmore where we were staying. Always anxious about flying, as we pulled away, Lehmann called out to Frances, “Pray for me.” Walking away Frances said, “I have more important things to do.” Lehmann shook her head: “When I die, only Suzy will miss me.”

In February, Lehmann had written: “I prefer the seats in the first class, and if you could arrange that I sit at the aisle opposite you both we are very able to talk!” The airlines put me across the aisle from them. Miriam insisted that I sit next to Lehmann—window seat—she and Lehmann sat across the aisle from each other.

The woman seated next to Miriam asked, “Isn’t that Lotte Lehmann?” My wife said she didn’t know. The woman said she was pretty sure it was. She asked had she ever heard her sing. “No.” The woman continued, “That was a pity because every time she opened her mouth—you —you wanted to cry.”

Lehmann and I chatted and occasionally glanced at the in-flight film. During a love scene Lehmann asked, “Dr. Schornstein, can you imagine anything more disgusting than kissing Lauritz Melchior? In opera we could fake it, in the movies they can’t.” She had great respect of Melchior as an artist, but found him tedious personally—“He only wanted to talk of stocks and investments.” This might have benefited her had she been interested—she credited Frances with bringing fiscal restraint and financial security into her life. “If I wanted to buy a new hat, Frances would say, ‘You have a hat.’”

At Kennedy Airport, John Coveney had a limousine waiting. The next evening we were included in a gathering of old friends: Constance Hope (1908–1977), Marcia Davenport (1903–1996), and John Coveney.

We saw Lehmann in the elevator a few times. We didn’t have tickets for the Met “farewell” and we didn’t travel back to California with Lehmann. Except for the exchange of letters, that was it for a while.

When Lehmann heard of Miriam’s third pregnancy, her response was practical. She thought we had enough—one of each. Her doctor in Vienna had told her how relieved he was that she never became pregnant. “He said he would have had to keep me under anesthesia for nine months.” It wasn’t that she didn’t like children: “But if they were to cry, I wouldn’t know what to do to help them.” Also, “They didn’t like me. Once when I was signing records at Sherman-Clay [a piano store in San Francisco], I saw a child standing in the line. I said when that child comes up to me it will cry. It did!”

From 1967

Master Classes at Northwestern the first two weeks in May. I attended five of the six. A colleague who thought me obsessed joined us for one. Afterwards I wanted to introduce him—but he was too awed to go back. The first class was devoted to the Schöne Müllerin cycle. In her introductory remarks she discussed the mental state of the love-stricken miller. She suggested he probably could have benefited from psychiatric attention and gave me a look. Before classes, she wrote out the English translations for the songs and took them with her. If she looked at them, I was never aware of it. She explained each song before the student began. Sometimes the student’s conception was totally at odds with hers—and that could be all right. “What you do is completely wrong! But I like it!” [Something Richard Strauss had said after she’d sung one of his songs.] She never was critical of a student’s voice. If they didn’t tune in to what she was doing, she would dismiss them with a quiet and polite, “Very good, very good.” If she was hard on a student—it was a good sign—there was something there. At one point in Europe she introduced me to a woman saying, “She had once been a student of mine and has a very pretty voice.” Which was code for why I had never heard her name until just then.

We had dinner together at the Orrington Hotel before the last two classes. Our waitress said, “Madame Lehmann, I would love to hear you sing.” LL: “Oh, I don’t do that anymore.” She: “I heard you were good.” LL: “Oh, I was good.” Without telling me, during the class that evening, she sang Brahms’ “Mainacht,” in a whispery baritone.…Her only stereo recording. [You can hear that in the chapter “Rare & Well Done II.”]

The next month our second son was born. We named him after the colleague who went to Evanston: Richard. We had told Lehmann we considering Gerd as a boy’s name. Lehmann was in Austria and wrote on the expected birthday:

Der Kaiserhof—Bad Gastein—June 18th 1967:

Dear Dr Schornstein—I am eager to know if today really is the day! Please let me know. Now the name, if it should be a boy: it has to be two or three syllables. Listen how that sounds: Gerd Schornstein. It should be Gerhard Schornstein. (I think Schornstein is a terrible name. Why did you not take out the “Schorn”?) Some more names: Eberhard, Frederick, Arthur, Raymond, Vernon. A girl: Marianne, AnneMarie, Liselotte, Anneliese, Margaret.”

It is raining and cold—and I would like to know why I wrack my brain about your baby’s name. The sun didn’t do that to me, one can be sure of that!….

Much love to you and Miriam,

/s/ Lotte

She expressed her joy at the successful end of the pregnancy and the hope this would be the last of our series: “Much love to you both and your too many children.”

During the summer she worked on felt appliqués for an exhibition at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. I wanted one. I knew it would be awkward if I contacted her directly. I contacted Ala Story who was the Museum’s second director and a Lehmann friend. She sent snapshots: “As I mentioned to you on the phone, the larger ‘Bad Gastein’ is really stunning, and personally I find it most satisfactory.”

Around this time she insisted that I call her Lotte. I have only referred to her as “Lotte” to others who were on a first name basis; otherwise, “Lehmann.”

Behind Lehmann’s back I bought it. When she learned who bought it, she was concerned that I was spending too much. “Look, Herman, if you prefer another picture, that will be O.K. with me. I have the feeling that the price is really too high for you. I cannot make it cheaper, I really worked for weeks daily some hours on it and the $1500 seems lousy in comparison to my working hours.” (Her fee for 2 Met performances.)

With this and the sale of slightly smaller piece she said her next trip to Austria was paid for—so why didn’t we join her!

Traveling together is the acid test of friendship. How tempting, though. While I agonized about the trip, Lehmann agonized about the purchase. Even after the picture transaction was completed, it wasn’t.

December 23rd 1967:

Dear Herman—

I have to explain all this unwelcome bickering about money. You see it is for me simply dreadful to SELL something to a FRIEND. When you bought that watercolor [oil] I did not know you at all and it was something exciting to me to sell a picture without any recommendation of somebody else. But now the situation is very changed. I would have loved just to GIVE you the big picture, but it was so much work involved that I had said from the beginning: ‘I only give this away if I get my price.’ Then YOU wanted it and I had such a bad conscience. It really is all absolutely the contrary of what you thought: I am far from being a business-woman. O God! So please forget the whole incident. I have suffered enough about it and you gave me sleepless nights, curse you.

(Without missing a beat—life planning—she was full-service.)

The best would be if you would come to Bad Gastein which I leave on the 9th of July. …. I hope you have a lovely Christmas—it should be so with these even for me enchanting children.

Your friend /s/Lotte”

Miriam decided I should go and she should stay home with our “too many children.”

December 27th 1967:

Dear Herman—Why in heaven’s name could Miriam not come with you? It would be lovely to have her to share in all the fun…. It’s so nice to make plans… Much love to you both.

Your,

/s/ Lotte”

From 1968

With Richard and a baby sitter, we returned to the Santa Barbara Biltmore and Lehmann’s 80th birthday gala. Melchior presented Lehmann with a copy of a sketch she’d given him illustrating their 1000th performance of Walküre—two ancients in wheelchairs, he with crutch held high. Handing it to her, she looked at it and said, “You know, I flattered you actually!”

Shortly after the birthday celebration I received a letter from one of her fans: “You know, our Lotte is really 85.” When I told her this she was furious. She admitted that early in her career she had wanted to fudge about her age. Going through customs, she had asked the inspector who was checking her passport, if he could alter the birth date—while explaining that would be impossible, he tipped the inkwell onto the offending page.

Santa Barbara—April 22 1968:

Dear Herman:

First of all, I am happy that no new misunderstanding would overshadow our friendship, and that your failure of writing comes only from your laziness…. (Then she listed many possibilities for this first of several trips.)

I really think Miriam should come along. I think Miriam would enjoy these trips just as much as you will. And I must say I feel rather embarrassed to burden you with a woman of 80—you look much too enterprising for that!!!!”

Miriam would not relent, so I flew off alone to Munich, where I rented a car, re-visited Garmisch where I had been stationed, then on to Bad Gastein and Der Kaiserhof. In all her travels Lehmann said she never had done her own packing. There was always someone. This time that someone who accompanied her and did the packing was Rose Palmier-Tenser (1902–1971). Born in Prague and a former student, in 1946 she founded the opera in Mobile, Alabama. She was fiercely devoted to Lehmann until the day she died.

I was quickly exposed as a “viel fresser.” To accommodate me, of course, we drove to Vaduz, the capital city of Liechtenstein for lunch—saddle of venison. The food at the Kaiserhof was worthy of a Michelin star. One of the highlights of the day was the posting of tomorrow’s menu in the elevator. Although I was never late, Lehmann was always sitting in the lobby waiting for me: “I will be early even for my own funeral.” The place was, probably still is, like a 19th century castle. Totally elegant—Frances couldn’t stand it. Lehmann would take the thermal baths right in the hotel. A local doctor had to prescribe the treatment. Lehmann was amused by her doctor who annually insisted, but never convincingly, that she had gall bladder disease.

Walking to town, we passed Gallerie Welz which had a Kasimir etching of Bad Gastein in the window. Lehmann suggested I get it—I bought it and another each time I returned. Besides the food, the days were filled by visits with old friends and students, interviews, side trips, and letter writing. We would sit on her balcony, have tea and enjoy the too-picturesque-to-be-believed scenery—with echoing cowbells.

After Bad Gastein, Lehmann, Rose, and I went to the Vier Jahreszeiten in Munich. We freshened up, unpacked, and met for lunch in their Café Walterspiel. It was late with only a couple of other tables of diners. There were at least three waiters attending us. I had the impression you could hurl a knife to the floor and someone would catch it before it hit. One waiter whispered in my ear to go and get a jacket. I motioned to an unjacketed man sitting nearby: “Yes, but he’s a child!” So up I got. Lehmann asked that while I was upstairs would I get her glasses. When I returned, acceptably garbed for the help, Lehmann said, “Don’t kill me, but I need my scarf—the air conditioning here is quite intense. It’s in my large suitcase.” Back up—but I couldn’t find the scarf. When I returned she was wearing it! “Herman, I’m terribly sorry. I found it in my purse.” I said, “It is really wonderful that you’ve reached 80, but you’re reducing your chances of reaching 81!” She enjoyed retelling this threat.

Conductor Robert Heger (1886–1978) and his sister came to dinner. We were alone in a back dining room. Too old for a regular position but knowing the entire operatic repertoire, Heger conducted all over Germany on stand-by. I asked, present company excluded, who was the finest Marschallin in his experience. “Siems.” Lehmann was delighted: “She was before me!”

From 1969

Santa Barbara—January 3 1969:

“Dear Herman,

I have not heard the broadcast by Cyril Richards. But I am sure he told the story of my one and only fainting spell in my life. [Covent Garden Rosenkavalier May 1938]… I tell you why I fainted: I was surrounded by an absolutely new cast; they came from Berlin and were all Nazis, especially Miss Lemnitz (Tiana Lemnitz 1897–1994) did not treat me very well. (She of the angelic floating voice was Octavian.) I remember that my voice was getting hoarse from inner tension, and instead of disregarding it she told me: ‘If you cannot go on, I shall sing for you’—and that did it! I could not bring out one tone, and left the stage, and the curtain had to fall. There really is not excuse for me, because the one rule in my life has always been ‘The show has to go on!’ But my husband was ill in Switzerland and his children were half Jewish through his first wife, and endangered in Vienna. I brought them all out, needless to say, by the way. I do not know whether you read my last book, “Five Operas and Richard Strauss.” I told this story there and also the rather hilarious ending when Sir Thomas Beecham told the people who were anxiously waiting outside my dressing room: “Mme Lehmann will be all right very soon. A very handsome young doctor is with her.”

I hope that—this handsome young doctor and his wife will join me in Europe and send all my love,

/s/ Lotte”

Miriam did come. Lehmann sent Tinta, her usual driver, to pick us up in Salzburg. The train was late. When we arrived, Lehmann, Rose, and another guest from the past, were at the dinner table waiting for us. After greetings and introductions, Lehmann leaned across my wife and asked me, “Herman, for some reason homosexuals find me interesting. Do you find me interesting?” I said, “No, not at all.” Frances said that when she first met Lehmann she would arrange dinner parties of people who were incompatible to see what would happen—I wonder if this was a remnant of that behavior.

Lehmann thought that some time spent in Schruns would be beneficial for Miriam, who had TB the winter before. So from Gastein we drove to Schruns and the Kurhotel Montafon. One morning, I went for a walk and met Lehmann sitting on a bench. Without breaking the silence, I sat next to her. After a few minutes she said, “When I signed the marriage contract with Otto, it was over.” I said nothing. She went on to say the only person she really ever loved was her mother. She asked how I was going to feel when she died. What she would miss most was the next sunrise.

In Salzburg we stayed at the Fondachhof where we met up with Maurice Faulkner (1912–1994) and his wife—he wrote articles about European music festivals for the Santa Barbara News-Press and the Saturday Review. Faulkner, of whom she was very fond, teased her about her dalliances: “Wasn’t that first man you had an affair with in Hamburg a tenor?” “No! He was a baritone!”

Lehmann was honored at a reception celebrating the publication of the Wessling biography and was presented with the Silver Mozart Medal from the Salzburg Festival.

She insisted I take her ticket for the festival’s opening performance: “Wild horses couldn’t drag me to another performance of Rosenkavalier.”

We occasionally talked about music. I liked the Beethoven song “Die Trommel gerühret.” This led to the story of how her husband’s first wife had invited her, as a surprise, to sing that song from behind a screen at his birthday party. The next day she was annoyed that I had brought it up, because she couldn’t get the tune out of her head. I asked if there was a particular song she enjoyed because of its effect on the audience. I thought it might be “Die Männer sind méchant” or “Vergebliches Ständchen” both of which always had the audience laughing. Her answer was “Die Krähe.” I think it was one of those questions that would get a different answer at different times. Preiser had given her an LP which included her early recording of “Erlkönig.” She gave it to me with the warning that both the conductor [pianist] and singer who made it “should have been shot.” [The Lied was taken fast so as to fit on a 10 inch 78rpm.]

I hadn’t particularly liked Fidelio which I had seen a couple of times. “You would have liked it with me,” and confirmed what I had read in Vincent Sheean’s book, First and Last Love. During a rehearsal of that opera, Toscanini had indeed called out, “You are the greatest artist in the world!” “I was at the height of my powers.”

One day, she noticed former Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg (1897–1977) in the dining room. After he left, she thought it was strange he hadn’t come over to say hello. He used to adjourn cabinet meetings when she sang Fidelio—he’d come to the opera house, listen to the Act II aria, and then reconvene the cabinet.

In a conversation about an artist who was having a difficult time and was drinking too much, I made the mistake of defending him by saying something about his having talent. “Talent! Phoui!! Talent produces!”

Coming to breakfast in minimum-risk shorts, I was greeted with a softly sung, “Ein nackte Mann, ihn muss ich fragen!” Lehmann asked how old I was: “Half your age.” With those blue eyes twinkling, she said, “If we had met years ago, we definitely would have had an affair.” I gulped, “I know.” Some time later she described her last romantic encounter. She was in her late 60s.

From 1971

This year the itinerary was Bad Gastein and London for the publication of her last book, Eighteen Song Cycles, Lehmann, Rose, Miriam, and me.

While we were sitting out on the balcony, the phone rang in the room. I answered. It was Lillian Gish (1893–1993): “May I please speak to Lotte?” After their conversation, Lehmann said, “That was very strange—Gish said she had been thinking about me all the way over from the United States and was so happy to read in the paper that I am in Gastein.” Two days later was set for the visit. The next day flowers arrived from Gish. The morning of the visit, Lehmann had figured it out—“I feel so guilty—those flowers were not intended for me. She thinks I’m Lenya!” Our middle child, Karl, had the same confusion.

The desk called. “Miss Gish is here.” I opened the door, she asked, “Where is Miss Lenya?” I said, with a sweeping gesture, “On the balcony.” Gish took one look and did a worthy double-take. Lehmann immediately said, “I know what happened.” They spent the afternoon chatting while I took pictures of the two new friends. They corresponded until Lehmann died. Gish later wrote an article for Opera News in which she stated how wonderful it was to have studied with Lehmann when she was young! A lesson on the reliability of source material.

At Heathrow, the custom’s officer looked at Lehmann’s passport and said, “There was once a singer with the name of Lotte Lehmann,” returned it to her and held her hand for a moment. I started pushing the cart with Lehmann’s luggage. Rose snatched it away. That was her territory. We stayed at the Hyde Park Hotel. The manager, Jonathan Dale Roberts, had a silver rose made as a welcoming gift.

The morning after Rose, Miriam, and I had gone to Glyndebourne to see Ariadne auf Naxos, Lehmann called our room—“Could you come up? Rose and I just had breakfast. Rose said she had a headache and went back to bed. Now she won’t talk to me.” I never dressed faster. Lehmann was pacing in the sitting room they shared, Rose was comatose and breathing her last labored breaths. I got Lehmann to sit down—called Miriam who asked how things were. “Grave. Come up.” Standing in the doorway between the bedroom and the sitting room, I saw Rose take her last breath. I called Mr. Roberts for an ambulance, and to have them enter through Rose’s door. Lehmann said she would have to go to the hospital—I said, “No.” “But Rose will be angry when she wakes up and I’m not there.” “Please get Rose’s husband’s phone number for me to call when I get back.” I took Rose’s passport which was next to the bed with half a chocolate bar—she was ten years older than she had told her teacher and diabetic. I followed the ambulance in a cab. Returning to the hotel, I was greeted by Mr. Roberts. I agonized about what to do—I had no idea about Lehmann’s cardiac status, there was a reception for her new book, a Lotte Meitner-Graf photo session, on and on. Mr. Roberts gave me the best possible advice: “Remember, whatever you do, it will be wrong.” I went upstairs. “How is Rose? Is she better?” I shook my head, “No, worse.” “How could she be?” Lehmann realized she had died and wept. I called Rose’s family in Alabama; her daughter arrived the next day. When I came back to the sitting room, Lehmann said, “So, let’s order lunch.” Exactly what Rose would have wanted. This rapid recovery haunted Lehmann. In London, she carried on with all the planned events…the photos were the last professional ones taken and are fabulous. When she returned home she refused visitors.

Frances asked me to come out from Michigan. She met me at the airport—and snatched my luggage out of my hands. (These women!) She told me what to expect.

At dinner Lehmann asked me how to commit suicide. What pills would she have to take? I said suicide by ingestion was unreliable—and aspiration pneumonia was likely and very painful. The only sure way was with a gun in your mouth. Frances interjected, “And I’m not going to clean it up.” This was helpful—the depression lifted as evidenced by future planning. Plus there was the stimulation of an exciting new student: Jeannine Altmeyer—“She’s a young me.” The student had a sponsor who became the replacement traveling duenna: Laura Lee Hammergren— but not without a rocky beginning.

From Frances—Santa Barbara—October 1970:

“Dear Herman:

The latest maniac—the “white roses and champagne” one whom Lotte had refused to meet is coming next Sunday. We shall see what we shall see. Boredom got the better of Lotte’s judgment. Of course that happens frequently and I have to cope with the results. This time I suspect I should have a straight jacket on hand.

However it looks as though I might land in a psychiatric ward before either Lotte or her adorers do.

Incidentally, we have acquired another dog—aged 16 and all that goes with that canine age. Lotte insisted she was to sleep with her, but two nights of it has convinced her that the animal should sleep with me. Actually that will involve much less getting up at night for me, so I am all for it.

Would that you were nearer. You are the best medicine for the diva.

Warmest regards to you and Miriam,

Gratefully,

/s/ Frances”

From Frances:

October 17, 1970

“Dear Mrs. Hammergren,

I am terribly sorry that Mme Lehmann was so rough with you. I knew what would happen if she asked you here and begged her not to as it has happened so often before and is heart rending to those who expect something different. After all she did warn you!

The reason she asked you was that you had been so kind to Jeannine that she felt it was very impolite not to invite you here. She never intended to do it again. That is her way.

As an artist no one can exude more warmth, but as a person that quality just doesn’t exist. She loves to be adored from a distance but any sentiment nearby is just not to be tolerated.

I won’t try to explain this, but just realize that she is a phenomenon and not a human being. There is nothing one can say about her of which the opposite isn’t equally true. She has no medium degree of anything, only extremes.

As to help—the only person who can help her is herself. I am delighted to report that for the last few days she has seemed to begin to realize that and is really very much better. About 60% of her trouble is psychogenic, but her knees and hip are very deformed. As she has never had a pain in her life, she just can’t bear to think that she will have it now and tries to keep from moving when it hurts—which of course is the worst thing for arthritis. She has been walking more the last few days and it is beginning to make walking easier.

Don’t worry about her. Just enjoy her art through her records etc. She will carry on in whatever way she wants to no matter how the rest of us stew.

Sincerely,

/s/ Frances Holden”

Der Kaiserhof—June 1st 1972:

“Dearest Herman and Miriam!

If I say ‘I miss you’ it is an understatement. It is really terrible that you are not here. I am stuck with a woman from Santa Barbara who is not to be convinced that I am—not an angel… I cannot live up to this… It drives me nuts. (Physically) Everything is much more difficult for me, my 84 years are not to be betrayed…One can only bear me when I sit. I rented a wheelchair but it stands in the corner. I cannot resign myself to it and prefer walking with much pain. You are both young—You may not even understand what it means to be so old and yet have a young heart and mind…”

In September 1973 Miriam and I began to legally terminate our marriage. Lehmann was very upset—for the children.

In late 1973 Lehmann wrote that she was going to the Salzburg Easter Festival to hear “Tristan & Isolde”—von Karajan had a new Isolde who was supposed to be “quite good.” She suggested I go. I saw that Jon Vickers was the Tristan and wrote that this should be a terrific experience. She wrote “You like his voice?” but allowed that it was impossible to discuss these things in a correspondence.

January 25 1974:

“I shall be accompanied of course by Laura Lee and it will be very refreshing to have you besides her angelic personality. (Nobody could call you “angelic!”)

Much love, your very, very old friend /s/Lotte”

Met Laura Lee at the Fondachhof. Definitely an angel. At dinner—I sat across from Lehmann, Laura Lee was next to her. We were very comfortable from wine with dinner and glüwein after. The conversation turned to Callas. Lehmann considered her a great artist especially gifted portraying crazy people. There was too much Callas talk for Laura Lee: “Why are we talking about her when we’re sitting here with the greatest of them all?” Lehmann looked at me wearily, “She’s talking about me.” In another effort to diminish Laura Lee’s esteem, with a pleading tone, “I hope that Otto was unfaithful to me. I certainly was to him.”

On the way to the performance, she described how much she had wanted to sing Isolde. She thought with the way von Karajan controls the orchestra she could have done it. We arrived at the Festspielhaus early. Von Karajan’s assistant, a count and former transvestite cabaret performer, led us through the back stage to the auditorium. Lehmann and Laura Lee sat in the front; I was in the back. After the first act, she waved for me to come down. “You were right about Vickers—and I never could have sung it, not even with von Karajan.” Regarding the new Isolde: “I find her bosom too distracting.” She was tired and was going back to the hotel; I was to stay to hear the rest of the performance. For the next days Lehmann raved about Vickers performance as though she had seen all three acts. She forgave von Karajan for not having acknowledged her presence in Salzburg. She was ashamed she even expected it: “He’s a genius.”

From 1976

This year her letters were dictated. There is none of the “shaky, small and scraggy ” writing Jefferson reports reflected in her signature.

January 1976:

“Dear Herman:

I am very much in favor of your marrying again—…

I feel very much better. Perhaps I was out of my mind when I felt so badly. Gastein now seems a possibility again.

With much love I am

Your old friend

/s/Lotte”

In May: “I should perhaps give up the whole idea of the trip.”

In July I planned a trip to California with my son, Karl, with our itinerary enhanced by Lehmann—Karl would enjoy San Simeon. She offered to help Karl distinguish between herself and Lenya.

When I spoke with her on the phone to finalize plans, she initially had difficulty recognizing my voice—then a letter came.

Frances Holden, August 21. 1976:

“Dear Herman:

Lotte just received your letter.

She says that I must write you immediately to tell you that she cannot see you in the morning but that you would be welcome in the afternoon of September 3rd.

She is rather miserable and all the medications she is taking seem to make her more so. It is very difficult for her to concentrate on anything and she is getting hard of hearing and tires very rapidly.

Do not expect the old Lotte. She is getting to be a very old Lotte. If you can cheer her up for a few minutes I shall be very grateful.

Hastily,

/s/ Frances”

When I got home on the 26th there were messages on my answering machine from friends who had heard her death announced on the radio and TV. I called Frances. Maurice Abravanel (1903–1993) had visited the night before—overstayed—and left Lehmann weeping about people not knowing when to leave. Frances said that Karl and I were to come ahead as planned!

I didn’t see Frances again for 13 years.

A gallery of Dr. Schornstein’s photos appears at the end of “Exclusive Photos II.”

The following is a Lehmann remembrance from Dr. Bernhard von Barsewisch of Gross Pankow, near Lehmann’s birthplace, Perleberg. He provides the necessary historical introduction for his association with Lehmann. The photo gallery illustrates various aspects of his article.

- Cabinet at Groß Pankow

- Entry hall Groß Pankow

- LL’s birthplace Perleberg

- LL’s restored piano

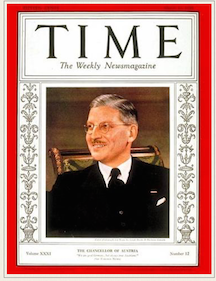

- Putlitz who first helped LL

- Baron who first auditioned LL

- Dr. B’s grandparents

- LL Akademie

- LL Woche at Groß Pankow w Dr. B

- Groß Pankow now

- Raciti w LL student Karan Armstrong

- Groß Pankow when LL visited

- Aunt & Mother of Dr. B

- Raciti, director of LL Woche

- LL plaque Perleberg Museum

- City Museum of Perleberg

- Bust of LL

- Terra Cotta bust of LL

- LL art

- LL art

- LL art

- Dr. B took this photo of LL at Orplid

- Dr. B at Orplid

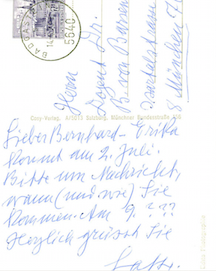

- LL post card to Dr. B

- X marks LL’s room in a post card to Dr. B

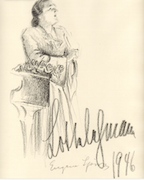

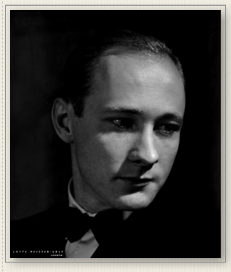

- Lithograph by Eugene Spiro

I was ten when I heard the name Lotte Lehmann for the first time. Early in 1945 we had fled from Perleberg before the Russian army came and were refugees in the small village Oedelum in the province of Hanover. When contacts became possible again my mother, Elisabeth von Barsewisch, née zu Putlitz, wrote a letter to Lotte to explain our beggarly situation. Lotte was so gracious to send CARE parcels containing precious items like coffee, cocoa, milk powder or corned beef. On those happy occasions my mother talked about Lotte, how my grandfather (Konrad Gans Edler Herr zu Putlitz/Gross Pankow) had sponsored an important part of her artistic education, about her international career, and her constant adherence to the zu Putlitz family. When in the 1930s Lotte sang as a guest in Berlin, she would provide tickets to the family. My mother told me about the beauty of Lotte’s voice, her clear diction, and the many roles she had sung.

As a young girl Lotte had been many times at my grandparent’s home Gross Pankow, together with my mother and my mother’s elder sister Erika (von der Schulenburg) who was of the same age as Lotte. She liked Erika more than Elisabeth, although the latter had more musical talent and could accompany Lotte on the piano. I believe Lotte found my mother too intellectual. In her first book Anfang und Aufstieg Lotte describes much of the life in Gross Pankow with the two sisters and my grandparents.

At the beginning of her professional carrier my grandfather heard Lotte in her first important role (Elsa) in Hamburg and fell deeply in love with her. She was shocked, for her it was as if God the Father had descended to earth and was a human being, a man. She tried to convince him that he had fallen in love with Elsa, not Lotte. But he wrote a poem for her and let her read it aloud. She was so excited that she had to support her trembling hands at the table. Her only thought was that this resembled exactly the horrendous cliché “The baron and his protégée.” The title and contents of the poem are unknown because my very austere grandmother commanded that all these papers had to be burned. By all means the title was not “The baron and his protégée” as Alan Jefferson (Lotte Lehmann, Eine Biographie, 1988/1991) had misunderstood my letter about that incident.

Once she began to sing in Vienna Lotte became a star of that important opera house. But she had a rival in her popularity, Maria Jeritza, another soprano. Many times they had to sing in the same opera, but their fans would gather and wait for them at different stage exits.

My first meeting with Lotte Lehmann took place in Bad Salzuflen when she visited my aunt Erika von der Schulenburg in the year 1966. My mother wasn’t alive at that time. At lunch Lotte absolutely dominated the scene and the conversation. My elderly uncle was almost mute, but my aunt listened to Lotte with veneration and so did I, being immediately caught by her strong personality. She spread an atmosphere of the “Great World” so different from my aunt’s dear but humble existence in post-war Germany. Because of her diabetes Erika was very careful with her diet, as careful as Lotte should have been. The latter asked her: “If you eat this desert, will you have pains?” She didn’t want to be so reasonable.

Lotte wore an elegant dress and I admired her jewels–but later on I learned that they were all imitations. She was not the type to accumulate valuables. In my first letter to her I addressed her as “Gnädige Frau” which would have been quite adequate for such an important lady. But she found that this title, in her mind, was reserved for my grandmother and I should call her Frau Lotte or simply Lotte.

During the following years when I worked as a resident [eye doctor] in Munich Lotte invited me several times to visit her in Bad Gastein. There she tried (in vain) to cure or at least soothe her arthritic pains. She was well recognized there by her old admirers and she complained about her publicity. So one year she went to Abano Terme for a change, but that was even worse, because no one knew her there. In Bad Gastein her place was the central room (a suite?) in the main hotel there, the Kaiserhof. I have her postcard with the prominent window marked. During those weekends she told me a lot about old times; not so much about music. I must admit that my opera understanding was very limited at that time.

Even more important was a full week I spent in Lotte’s “crazy household” (her expression) in Santa Barbara in the year 1972. It was my first travel to the U.S., mainly a professional one starting with a conference on retinal diseases in Miami. But between visits to important hospitals and colleague acquaintances I found some time to see private contacts. Number one of course was Lotte Lehmann with Frances Holden at Hope Ranch Park, Santa Barbara. This was primarily Frances’ possession with a view over Eucalyptus trees and Macchia vegetation [broad-leaved evergreen shrubs or small trees] towards the Pacific Ocean. The house was a complex of compartments and later additions, confusing but with a particular charm. The furniture inside was comfortable but not precious. Frances had a large library full of her books; one room was entirely decorated with Lotte’s watercolors illustrating the Winterreise. The living room had a large window with a view to the ocean and to a feeding vessel for humming birds. A beautiful ceramic bust showing Lotte as a deeply moved singer of Lieder was in the garden with its exotic vegetation.

There were spoiled dogs begging at the dining table, never believing in Lotte’s “I have no more.” Rigid rules were not one of Lotte’s strengths in private life. Not knowing about her diabetes I had brought a small Sacher Torte from Farmer’s Market in Los Angeles. It was served as a desert when several guests were present and Lotte declared that her doctor would not allow her to eat one bit. The guests in chorus appeased her by saying: “But one piece must be possible!” So with that general pardon from all others (except Frances) she could enjoy the forbidden piece with a good conscience.

When Frances cleared the breakfast table Lotte would cry after her: “And don’t forget the birds.” I don’t recall what birds they had at that time. At least it was no longer the Beo whom they had taught to say: “I can talk, can you fly?” or “It’s time to go.” Frances kept her countenance. In her devotion she was really an elephant in tolerance. If anyone kept things in order it was she and not Lotte. More than that: Lotte had lost every sense for practical things and for money. For example, she had a cousin married to a doctor Bock. As young and poor immigrants in the 1940s they had a boy (who later became a heart surgeon) and Lotte sent them a precious christening dress. This was so costly that the young couple didn’t use it. They brought it back to the store and exchanged it for the complete furniture of the baby’s room.

During the war Lotte toured Australia and explained to Frances, when coming back she wanted to see new furniture in the living room. On her return she found all the same pieces as before and reproached Frances who had not fulfilled that wish. Frances replied: “From which money should I buy new furniture?” “But I sing, I do earn money, a lot of money!” “Yes you do, but you travel, you live in costly hotels and need new dresses galore; what remains is not enough for new furniture.”

Without the organization and constant support by Frances, Lotte would have died in poverty. She was really lucky to have such an intelligent and well-read friend who had kept her veneration and love over the decades. Both told me many details about Lotte’s career and their life together.

Here are examples: When Lotte got an invitation to sing as a guest in Paris she prepared to take her golden gown she used for the role of Elsa. But some envious person had hidden this gown and she had to travel without it. Fortunately in Paris they had a substitute that was even more beautiful.

After the war Bruno Walter wanted to engage Lotte for Edinburgh, but she refused using very weak excuses. At that time she was acting and singing in a film, [MGM’s Big City] that was true. But in reality she was afraid to present her voice to the European public after such a long period.

This was the time when she concentrated on Lieder. At one point she was not content with one agent and so she hired a new one. The new agent organized three evenings in New York en bloc, but with different programs that all sold out.

For a radio broadcast Lotte was interviewed together with Maria Jeritza who had lived a very different life, being divorced several times and with financial success. They exchanged memories, but when Lotte quoted any certain year, Madame Jeritza, eager to seem younger, tried to correct the dates.

Wolfgang zu Putlitz, a cousin of my mother who lived in the German Democratic Republic [then East Germany] as a partly convinced communist, tried to lure her to visit her birthplace Perleberg. Originally Lotte was stimulated by that idea and made plans to drink coffee with old schoolmates. But when she realized that this visit would be exploited on a political level she changed her mind and wrote a refusal letter (which I have in my hands) again using very weak excuses.

In Santa Barbara I was especially touched by one situation. In the afternoon Lotte would sit in an armchair to listen to old records Frances had put on the player. Lotte in contemplation heard her own voice, only moving her lips to the words. I thought how unjust is fate. Contemporary singers get technically brilliant recordings, while Lotte’s beautiful lyrical voice had to cope with technical imperfection and the scratches of the aged records.

One bold question I did ask her: Why with her musical ear she had made so little attempt to eliminate her continental pronunciation and get closer to an English or American accent. She replied: “Zey like zat.” She felt that this imperfection (no “th” ever) did by no means diminish her artistic authority. I am so glad that in the Hickling documentation, besides reading, one can also hear her vivid talking in interviews, all so real and extremely touching. These scenes evoke so many memories.

I took a photograph showing Lotte in a sumptuous silk dress walking on crutches among the succulents of the park. She didn’t like the picture. It reminded her of her duty to painful exercise and she found she was looking too old. But as a portrait taken 4 years prior to her death it is quite realistic.

During her third carrier as a teacher with master classes Lotte continued to write books on opera singing. Later she looked for other outlets for her artistic emotions. Felt applications and ceramic mosaics were rather amateurish but her paintings with watercolors were absolutely great. Originally she got the brush in her hands to calm herself down prior to recitals. From dilettante beginnings like the Roland statue in Perleberg she had progressed to illustrations of opera scenes, some with disrespectful comments (e.g. Lohengrin in the bedroom: “And then they made a terrible mistake, they sang and they sang and sang”).

Finally she had developed a very particular own style with laying a pattern of India ink lines over the colors of fantastic compositions, e. g. taken from drift wood decorations. She was so kind to let me select three of her chef d’oeuvres and these hang in the entrance hall of Gross Pankow, my grandparents’ mansion which I had bought back in 1991 after the Wall had fallen.

Here at the authentic place where Lotte sang to my grandparents I can pass on my Lehmann memories year by year to the participants of the Lotte Lehmann-Woche und the Lotte Lehmann-Akademie. The purpose is that they should realize that “Lotte Lehmann” is not an empty name but stands for a great voice, an outstanding talent, and a particular vita that had begun here in our own region. Lotte’s birthplace, the small city of Perleberg, honors her memory by these highly successful annual singing courses given by international professionals to beginners and very advanced students.

Recently, in 2016, a bronze bust of Lotte by a local artist Bernd Streiter has been unveiled close to the Lotte Lehmann promenade and not far from the house where she was born.

Many thanks to Prof. Dr. Barsewisch for the article above.

Beaumont Glass describes the esteem in which Lehmann was held in his biography, Lotte Lehmann: A Life in Opera and Song, on the occasion of the last nostalgic evening of the Metropolitan Opera at its old house: “When Lotte Lehmann, proudly erect beneath her years, came forward, everybody stood up.”

Beaumont Glass describes the esteem in which Lehmann was held in his biography, Lotte Lehmann: A Life in Opera and Song, on the occasion of the last nostalgic evening of the Metropolitan Opera at its old house: “When Lotte Lehmann, proudly erect beneath her years, came forward, everybody stood up.”

• Here’s an anonymous fan’s memory of Lehmann’s last Met appearance:

Closing Night of the Old Met, April 16, 1966, with a sentimental gala farewell performance featuring nearly all of the company’s current leading artists. Lehmann hadn’t sung there since 1945, but I doubt that anyone who was there will ever forget Leopold Stokowski, conducting the “Entrance of the Guests” to the music of Tannhäuser; guests who included Lotte Lehmann, Giovanni Martinelli, and about sixty or so other great Met legends. At the end everyone sang “Auld Lang Syne” so that the audience could say that, through that din, they did hear Martinelli, Lehmann, Pons and the others sing once again.

My thanks to all these fans, students, and friends who have helped in the analysis and appreciation of Lehmann’s personality, as well as her musicianship. Their interest in the Lehmann legacy touches me deeply, because her vibrant legacy has so profoundly influenced me. This volume and Volume I stand as my tributes to her.

• Horst Wahl was one of Lehmann’s early audio engineers, working with her at the point that the recording industry was shifting from acoustic to electric. Judy Sutcliffe and I visited him in 1989 when we were conducting our Lehmann research in Germany and Austria. He was in his 90s at the time, had clear recollections of his work with Lehmann, and revealed that there had been more than a professional relationship between them. Wahl sent letters to Judy and she has shared them in the gallery below. I’ll provide translation for them on the following pages.

Translations of Horst Wahl’s letters

Received 14 September 1989

My dear Judy Sutcliffe,

Many thanks for the wonderful picture of my beloved Lotte. Yes, you’re right, that is exactly the hat that she was wearing when I first met her. You will admit that one couldn’t recognize her face at all when she had lowered her head. How young she appeared in 1926, even though she was already 38. I never had the feeling that there was an overwhelming age difference between us. Especially when she called me “her boy” (which was an honor when I thought of Octavian. [In Der Rosenkavalier, the Marschallin refers to Octavian as “Mein Bub.”] By the way, your wonderful color photo from Lotte’s film now hangs over my desk and greets me each day that I still live.

Today I enclose for you a small manuscript that you can perhaps print in the third issue of the Lotte Lehmann League [newsletter]. It involves the longed for complete appearance of the recording of her Rosenkavalier and will provide a welcome addition to the discography. By the way, I have sent Mr. Hickling his requested corrections to the Lehmann discography and given him advice on ways that he can improve it.

Has he told you that you lost two pearls of your chain? I would happily send them to you if they’re worth something to you.

It was a beautiful, content-rich day, when you both were here; I think often on it.

I have you in my heart and send you many greetings, also from my wife.

/s/ Your Horst Wahl

Dated 29 September 1989

My dear Judy Sutcliffe,

I have happily just received your warm-hearted, interesting, and humorous letter. Thank you also for the beautiful portrait of Dr. Holden; I am always astonished at Lotte’s drawings: what a great second-art (also with Caruso). The attractive anecdotes of Dr. Schornstein have brought me closer to the “late Lotte.” You are completely correct, Lotte was different with men than with women. I want to tell you something today, which I (outside of my wife naturally) have up until now told nobody. With you I know, that I can do this, in spite of our short acquaintance. Also Frances would tell you the same.

When Lotte and I met, I was naturally very shy due to the difference in our ages and the fact that I was with her, the greatest of her “Fach” of her day, [the greatest soprano of her day]. I was simply dying in awe of her. But Lotte very soon took the initiative, as she saw where things stood between the two of us.

One day she said to me, “You love to read Honoré de Balzac. Do you remember this quote from him: ‘What can be sweeter than the love of a ripe [mature] woman for a youth, whose first love she is’?” That broke the dam…