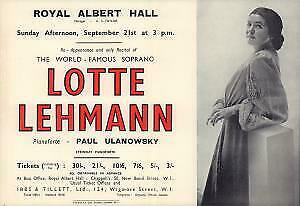

Paul Ulanowsky was Lehmann’s principal accompanist from 1938 until 1951, performing with her over 50 times in New York alone. She called him “the ideal accompanist for me. We understood each other musically in perfect time.” He had the ability to adjust to the demands of the moment, which, given Lehmann’s rhythmic freedom, was necessary. Concerning improvisation, he said, “The ideal is that you prepare something extremely well… and then at the moment of performance you make yourself forget (all that) and create, as it were, completely from scratch.” Listen to Ulanowsky speak to Lehmann, then Lehmann speaks about him and finally her previous pianist Balogh. Thanks to his son, we have many of the letters Lehmann wrote to Ulanowsky.

Paul Ulanowsky was Lehmann’s principal accompanist from 1938 until 1951, performing with her over 50 times in New York alone. She called him “the ideal accompanist for me. We understood each other musically in perfect time.” He had the ability to adjust to the demands of the moment, which, given Lehmann’s rhythmic freedom, was necessary. Concerning improvisation, he said, “The ideal is that you prepare something extremely well… and then at the moment of performance you make yourself forget (all that) and create, as it were, completely from scratch.” Listen to Ulanowsky speak to Lehmann, then Lehmann speaks about him and finally her previous pianist Balogh. Thanks to his son, we have many of the letters Lehmann wrote to Ulanowsky.

In a Studs Terkel interview Ulanowsky spoke about Lehmann’s Town Hall Farewell Recital. Ulanowsky on Farewell Recital The missing portion of the piece is Lehmann’s Farewell speech. Terkel’s complete Ulanowsky interview

In October 1967, shortly before his death, this is what Ulanowsky had to say about the union of the poetic word and music in a Lied.

Dr. Ludwig Zerner of the University of Illinois School of Music spoke a beautiful memorial tribute to Ulanowsky.

You may enjoy listening to Ulanowsky teach a masterclass on Wolf’s Du denkst mit einem Fädchen. Du denkst Doch eben nicht in dich

Here’s what Ulanowsky had to say about Bruno Walter, specifically in a performance of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde in which he’d played piano. Ulanowsky on Bruno Walter

You can go to the website his son has put together to read many remembrances of Ulanowsky, as well as read his book on The Art of Song and Accompaniment. There is also a discography, quotes, reviews and a biography.

Among the many attributes that Ulanowsky possessed was the ability to memorize the music and play in any key, which also suited Lehmann’s wishes, as she often asked him to change keys.

LL made a book of index cards for each program on tour. Notice the arrows which Ulanowsky inserted to let him know whether to transpose 1/2 or a full step

In a 1966 master class demonstration of Strauss’ Cäcilie, Ulanowsky, in a whisper which we heard in the balcony, asked in a pleading, hopeful voice, “Mme., what key?” He, like all of us, wanted to hear her, even at the age of 78, sing this exciting song. She replied. “The original key! I’m not going to sing it…I’ll just speak it through.” And so she did, though there was pitch to the words and a projection of emotion that allowed us to understand what critics and audiences had raved about years before.

As Ulanowsky himself said, “The most important thing is the honesty with which you try to identify yourself…with the composer and poet. To go back to what they wanted…in their combined work of sound and word.”

Ulanowsky was born in Vienna in 1908 and lived until 1968. He accompanied many great artists besides Lehmann and was also a gifted teacher. I had the pleasure of hearing him accompany Ernst Haefliger at Carnegie Hall and teach at Yale Summer School of Music and Art. Later I turned his pages when he played Bach Aria Group concerts at Town Hall. Each occasion offered the opportunity for me to enjoy his ready wit and to hear Lehmann stories.

Regarding Lehmann’s Town Hall farewell recital in 1951, Ulanowsky said that only a few people knew, and he wasn’t among them. She asked him to remain on stage while she spoke to the audience, telling them that it was indeed her farewell recital in New York. Ulanowsky remembered, “There wasn’t a tearless eye…except Lotte Lehmann. With incredible discipline she carried through the speech and the rest of the program (until) just a few seconds before the end…when she broke down. This was not a studied thing. She didn’t expect it to happen and as she went . . . out the door of Town Hall she said to me, ‘This is terrible!'”

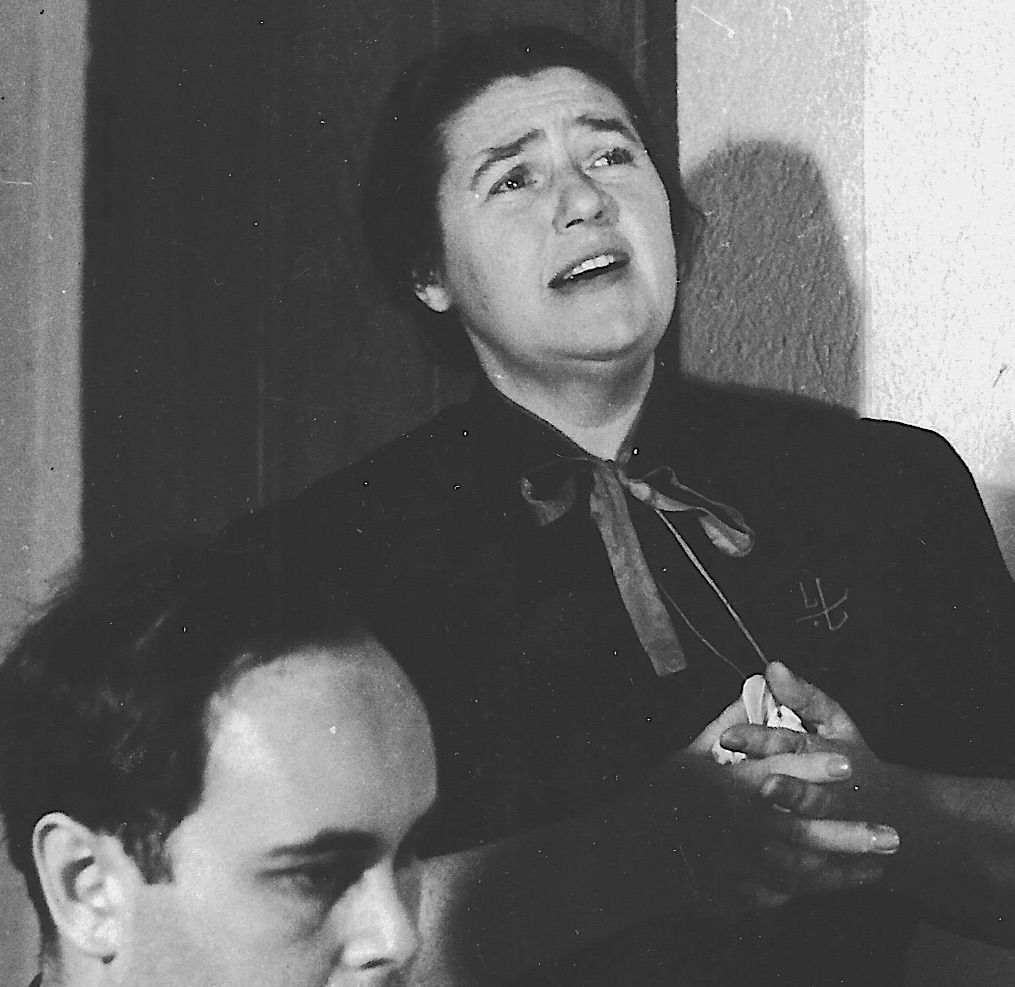

Besides the Town Hall masterclass, Lotte Lehmann and Paul Ulanowsky also gave others, as this photo from May 1966 at the Conservatory of Music, University of Missouri, Kansas City attests.

Let’s read what Beaumont Glass had to say about the beginnings of the professional relationship between Lehmann and Ulanowsky: “Ernö Balogh could not come to Australia. He was about to get married. Lotte engaged Paul Ulanowsky as her accompanist for the  Australian tour and the concerts on the way. It soon became clear that here was the ideal accompanist for her. She felt totally free with him. She could follow a sudden inspiration during a performance, fully confident that he would be with her. She could ask for a last-minute transposition as she was making her entrance, and know that he would carry it off without a flaw. She thought of Bruno Walter as her teacher and was forever grateful for the insights he shared with her; her recitals with him were among the artistic highlights of her career. But she felt more herself with Ulanowsky.

Australian tour and the concerts on the way. It soon became clear that here was the ideal accompanist for her. She felt totally free with him. She could follow a sudden inspiration during a performance, fully confident that he would be with her. She could ask for a last-minute transposition as she was making her entrance, and know that he would carry it off without a flaw. She thought of Bruno Walter as her teacher and was forever grateful for the insights he shared with her; her recitals with him were among the artistic highlights of her career. But she felt more herself with Ulanowsky.

Furthermore, she found Ulanowsky charming as a traveling companion and very witty. He knew how to make her laugh. Sometimes, before a concert, she would be near hysteria with nerves. Everything seemed to be going wrong. A quiet, humorous remark from “Paulchen,” and the sun would come out again.

At first she missed the warmth—the “Herzenswärme“—of Balogh. Ulanowsky was still new to her, and as yet understandably reserved. She wrote to Constance Hope, on May 2, that she would not dream of making Ulanowsky her regular accompanist, much as she loved singing with him; she felt too strongly the bond of friendship with Balogh to allow herself to hurt him, personally or professionally.

Nevertheless, by June 19 it was obvious to Lotte that she would have to make the change, however painful. Her decision and the struggle it cost her are clear in this letter to Frances Holden:

I found in Ulanowsky an absolutely ideal accompanist….I am determined to try to free myself [from Balogh]. You know that that will not be easy for me. It is cruel, from the human point of view. I must find a way to make myself free without hurting him, and without doing damage to his career. But I see now with Ulanowsky how much easier and more wonderful my recitals will be when I have him at my side. Toscanini was right when he said to me that there is no friendship and no considerateness in the realm of art. But it is very hard for me to do something like that.

For Balogh it was surely a very bitter loss. A world career is rarely made without giving injury somewhere. Relationships are sacrificed along the way, inevitably. But the break was as painful to Lotte as it must have been to him.

She tells about the switch in an article (as yet unpublished) about her accompanists: …In 1937 I received a contract with the Australian Broadcasting Commission. Now Balogh had just got married and would have faced a separation from his wife only with a heavy heart. I was somewhat at a loss. Naturally, if I had insisted that Ernö come with me to Australia, he would probably have done so. But I did not particularly want to take a love-sick Romeo along….So, with Ernö’s blessing and fervent prayers, I searched for another accompanist for Australia—and found him! Paul Ulanowsky. I stole him, I behaved very unethically: he was accompanying Enid Szantho, the excellent mezzo-soprano, in a lieder recital that I happened to hear. After five minutes I whispered to my husband: “He’s the one, I want to have him!”

When I asked him if he wanted to come with us to Australia, he was equally unethical and immediately agreed, leaving Szantho, who had every right to be incensed. Blissful and free from any twinges of conscience, however appropriate, I left for Australia with my prey. I must have a very flexible conscience, for I have never regretted my sin….

Lotte, Otto, and Ulanowsky started their South Sea adventure on March 31, 1937.”

So writes Glass. He quotes Lotte Lehmann in her address to the audience at her Farewell Recital in NYC in 1951:

So writes Glass. He quotes Lotte Lehmann in her address to the audience at her Farewell Recital in NYC in 1951:

Paul Ulanowsky has been the ideal accompanist for me.. [prolonged applause] We understood each other musically in perfect harmony, and always when I sang with him it was as if the hands of an angel have supported me—now don’t you get conceited! [laughter from the audience] I only mean, you know, you were an angel when you played. Otherwise you were not so angelic. [laughter again]

He has a very keen sense of humor, and you can believe me that that is a great asset on concert tours where many incidents happen, and where one gets hysterical and upset. But he smoothed out everything and always made me laugh and turned every tragedy into a joke—really he’s quite a wonderful guy! I hope that my successors who will sing with him in future will be as happy as I have been with him musically and personally. Thank you, Paulchen.”

You can hear the whole Farewell Speech.