This is a list of the famous conductors under whom Lotte Lehmann sang. The word “famous” is relative. In their time, and sometimes their city, they were famous. As time moves on, their fame diminishes. So I’ll try to write a mini-bio on the conductors of lasting greatness and also place them in Lehmann’s life. Some were pivotal, some peripheral, but all deserve to be on this list.

There were also many conductors with whom Lehmann sang a lot, who were the regulars in the orchestra pits of Hamburg, Vienna, Paris, Chicago, New York and San Francisco, whose hard work should be respected, but whose names are not part of conducting history. You can see their names in the Lehmann Chronology.

The following are the conductors, who in my estimation, deserve some place in the imaginary “Conductors Hall of Fame,” and who also worked with Lehmann. As you may notice, they include almost every major conductor active during Lehmann’s career (1910-1951).

Maurice Abravanel (1903–1993) was at the Met at the end of Lehmann’s career and conducted her many times there. He went on to become a strong force at the Music Academy of the West (1954–1979) and worked well with Lehmann there. I had the privilege of playing bass under his baton for three summers at the MAW. His major fame, however, comes from the fact that he brought the Salt Lake Symphony (Utah) to a high degree of polish. He conducted there for 32 years!

Maurice Abravanel (1903–1993) was at the Met at the end of Lehmann’s career and conducted her many times there. He went on to become a strong force at the Music Academy of the West (1954–1979) and worked well with Lehmann there. I had the privilege of playing bass under his baton for three summers at the MAW. His major fame, however, comes from the fact that he brought the Salt Lake Symphony (Utah) to a high degree of polish. He conducted there for 32 years!

John Barbirolli (1899–1970) was a well-known English conductor and cellist, especially respected for conducting the Hallé Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic (1936–1943). He conducted many other orchestras and made some excellent recordings. Sir John was not a significant conductor in Lehmann’s career. He traded off evenings at Covent Garden in the 1930s with Thomas Beecham and that’s how he came to conduct Lehmann.

Thomas Beecham (1879–1961) was an English conductor and a major influence in the musical life of Great Britain. Besides symphony orchestra conducting, his opera work was highly respected. Beecham conducted many of the opera appearances Lehmann made at Covent Garden. These were often broadcast on the radio and there’s hope that some of these operas with excellent casts, good orchestras, and the important conducting of Beecham will be found as recordings.

Leo Blech (1871–1958) was in his time one of the most famous conductors, though he also was a composer. He conducted in Berlin at the Königliches Schauspielhaus (later the Berlin State Opera or Staatsoper unter den Linden). It is there that he conducted Lehmann in Wagner and Strauss roles. One of Lehmann’s favorite encores, especially early in her recital career, was his “Heimkehr vom Fest.”

Artur Bodanzky (1877–1939) was the Metropolitan Opera major Wagner “house conductor” from 1915 until his death. Not really known outside of his work for the Met, and not highly respected during his lifetime, the surviving recordings made from the live Saturday radio broadcasts, show a real command of the scores. He conducted Lehmann at the Met in many of her Wagner and Strauss appearances (more than any other conductor there).

Fritz Busch (1890–1951) conducted most famously (in Germany) in Dresden, where he led Lehmann in the world premiere of Intermezzo by Strauss in 1924. After 1933, because of his outspoken opposition to the Nazis, he conducted in South America, Scandinavia and England (Glyndebourne Festival Opera). He had lots of family connections in the classical music world, being the brother of violinist Adolf Busch (who was especially famous for founding the Busch Quartet, and for playing with Rudolf Serkin, who married his daughter) and brother of cellist Hermann Busch.

Antol Doráti (1906–1988) the great Hungarian-born conductor (and composer) who, after studying with Bartok, was able to conduct the world premiere of his viola concerto with his Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, where he conducted for 11 years. He conducted other American and European orchestras as well. He only conducted one Lehmann concert, and that was with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in 1939.

Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886–1954) was one of the most respected German conductors of his time. But because he stayed in Germany during the Nazi period, his reputation, especially in the U.S., was badly tarnished. Possibly because of the Nazi association, Lehmann didn’t often speak of him in her interviews, but she sang under his direction many times, including concerts as well as operas in Berlin, Paris, and Vienna.

Robert Heger (1886–1978) was not a famous conductor outside of Europe. His principal claim to fame was the recording of Der Rosenkavalier that he made with Lehmann, Schumann, et al. He conducted Lehmann many times at Covent Garden, but was most conspicuous in her life at the Vienna Opera. Lehmann probably sang more under his baton than any other single conductor (82 performances!). He was also a composer and wrote a cycle of songs to Lehmann poems. His Nazi associations hurt his post-war years.

José Iturbi (1895–1980) was a Spanish conductor, harpsichordist, and pianist. Famous from his appearances in Hollywood films of the 1940s, he first conducted Lehmann in 1937 on the Ford Sunday Evening Hour and in 1938 when he was the conductor of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra.

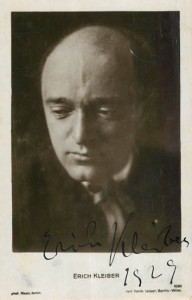

Erich Kleiber (1890–1956) was one of the great conductors of the 20th century, but he had only limited contact with Lehmann. In 1932, he conducted her as Sieglinde for the Berlin State Opera. In a 1938 Covent Garden performance of Der Rosenkavalier, during the first lines of the Marschallin’s monologue in the first act, Lehmann felt faint and stopped singing. So he didn’t conduct much of her performance!

Otto Klemperer (1885–1973) was an important German conductor who, despite his psychological problems, worked successfully with orchestras in both Europe and the U.S. He had begun his work with the Hamburg opera the same year Lehmann did and conducted her first big success there as Elsa in Lohengrin. He held many positions in his life, but the ones that mattered for Lehmann were his time at the Kroll Opera in Berlin (1927–1931) and the Los Angeles Philharmonic (as late as 1944 in the Hollywood Bowl). As a guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic, he conducted Lehmann at Carnegie Hall. His fascinating career is certainly worth reading about.

Hans Knappertsbusch (1888–1965) was a highly respected German conductor, especially well-known for his Wagner and Richard Strauss interpretations. He had problems with the Nazis and left Germany to conduct at the Vienna Opera, where he paced many Lehmann appearances. In 1937 he conducted a Rosenkavalier performance with Lehmann at the Salzburg Festival. Before those appearances, as early at 1926 he had conducted her Eva in Die Meistersinger in Munich.

Erich Korngold (1897–1957) was a wunderkind composer of operas. Though Lehmann sang in several of his operas, he only conducted her in his Der Ring des Polykrates in 1919 and 1920 (at the age of 23!). Korngold is best known for his film music composed in Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s.

Serge Koussevitzky (1874–1951), a Russian-born conductor, is remembered mostly for conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra (1924–1949). During that time, he made significant recordings with the orchestra and commissioned many works, including Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G, Gershwin’s Second Rhapsody, Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 4, Hindemith’s Concert Music for Strings and Brass, Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra, and many others. Not an important conductor in Lehmann’s career, he did conduct her in two concert performances in 1935 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Clemens Krauss (1893–1954) was a highly respected Austrian conductor, associated both professionally and personally with Richard Strauss. He became the director of the Vienna State Opera in 1929 and was also connected with the Salzburg Festival. He conducted Lehmann many times in both these venues (as early as 1922), but because his mistress and later second wife, Viorica Ursuleac, sang many “Lehmann” roles he, of course, tried to engage Ursuleac. This caused great friction between him and Lehmann.

Josef Krips (1902–1974) was an Austrian conductor. He studied with Weingartner (see below) and became his assistant at the Vienna Volksoper. He conducted orchestras such as Karlsruhe, but was most active in Vienna until the Anschluss. He returned to Vienna after the war and also conducted the London and San Francisco Symphony orchestras, as well as leading operas at the Met, Covent Garden, and Berlin. Krips was not extremely important in Lehmann’s career, having conducted her (mostly in Der Rosenkavalier) at the Vienna Opera in 16 performances between 1933 and 1937.

Erich Leinsdorf (1912–1993) was born in Vienna and studied conducting at the Mozarteum in Salzburg and later in Vienna. From 1934 to 1937 he assisted Bruno Walter and Arturo Toscanini at the Salzburg Festival. In 1937 he began as an assistant conductor at the Met and since the Nazis took over Austria shortly thereafter, he remained in the U.S. After Bodanzky’s death in 1939, Leinsdorf took over the German repertoire at the Met. He was the music director of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra (1947–1955) and he was music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (1962–1969). After that he guest-conducted. He conducted at least 30 performances at the Met that included Lehmann. It is said that she recommended him for that post.

Pierre Monteux (1875–1964) was a renowned orchestra conductor who began in Paris as a violist, playing under Nikisch, Mahler, and Strauss. He conducted the Ballets Russes in Stravinsky’s Petrushka and The Rite of Spring; Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé; and Debussy’s Jeux. He conducted at the Met, and symphony orchestras in Boston (1919–24), Amsterdam (1921–34), and San Francisco (1936–1952). His students included Neville Marriner, André Previn, Lorin Maazel, and Seji Ozawa. He conducted Lehmann in 1929 in Amsterdam, in 1936 with the Orchestre symphonique de Paris and at least three times with the San Francisco Symphony.

Dimitri Mitropoulus (1896–1960) was a Greek conductor, pianist and composer. He served as the principal conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra (1937–1949), thereafter working with the New York Philharmonic until his protégé Leonard Bernstein succeeded him in 1958. He conducted as well as accompanied Lehmann at the piano in Athens, Greece, and conducted her for a concert at La Scala, Milan (both of these in the 1930s).

Charles Münch (1891–1968) was an Alsatian conductor, specializing in the French repertoire and highly respected for his time (1949–1962) as the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He led the Lamoureux Orchestra at the Salle Gaveau, in Paris for one performance that included Lehmann ( in which she sang Beethoven and Wagner arias).

Arthur Nikisch (1855–1922) was considered the preeminent conductor of his time. Although Hungarian, he worked internationally, holding posts in Boston, London, and Berlin. He was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra from 1895 until his death. He conducted Lehmann about eight times at the Hamburg Opera in 1915 and 1916.

Eugene Ormandy (1899–1985) was a Hungarian-born conductor. Though he conducted the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, his fame rests primarily on his 44-year tenure with the Philadelphia Orchestra. The many recordings he made there have have given him lasting fame. In 1934, while still in Minneapolis, he conducted Lehmann in arias and songs. In 1948 he conducted the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra where Lehmann sang Strauss songs.

Paul Paray (1886–1979) was a French conductor best remembered for his tenure of more than a decade with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra (1952–1963). He conducted Lehmann in Monte Carlo in 1929 and 1931.

Fritz Reiner (1888–1963) was a prominent conductor of both opera and symphonic music. The pinnacle of his career was his work in the 1950s and 1960s with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra with which he made many recordings. He had studied in Budapest with Bartók, worked with Richard Strauss in Dresden, and became Principal Conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra in 1922. He also conducted the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (1938–1948). With Lehmann, he led a Rosenkavalier with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1934, and a famous 1936 San Francisco Opera performance of Die Walküre with the all-star cast of Melchior, List, Schorr, with Flagstad as Brünnhilde. This was partially recorded.

Artur Rodzinski (1892–1958) was a Polish conductor of opera and symphonic music. His time with the Cleveland Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic in the 1930s and 1940s is especially important. He conducted Lehmann as the Marschallin with the Cleveland Orchestra in 1935 and in concert with the New York Philharmonic in 1937.

Victor de Sabata (1892–1967) was an Italian conductor, specializing in Verdi, Puccini, and Wagner. He is renowned for his many years at Milan’s La Scala (starting in 1921) where he succeeded Toscanini, with whom he is often favorably compared. He conducted some of Lehmann’s appearances as Desdemona at the Vienna Opera in 1935 and 1936.

Franz Schalk (1863–1931) was an Austrian conductor, best known for his association with the Vienna Opera. He actually studied with Anton Bruckner! His association with Lotte Lehmann was profound. Schalk gave Vienna the local premiere of Pfitzner’s Palestrina, with Lehmann cast as Silla, and Die Frau ohne Schatten by Strauss, with Lehmann as the Dyer’s Wife. Especially for Lehmann, Schalk revived the title of Kammersängerin (literally “Chamber Singer,” from the days of the monarchy when singers were honored by the appointment to sing for the emperor in his chamber, a sign of his highest esteem). She was the first singer to receive that designation since the collapse of the monarchy. She officially became Frau Kammersängerin Lotte Lehmann in 1926. For the Beethoven Centennial in 1927 Schalk conducted Lehmann’s first Leonores. He wrote: “A great, overwhelming, radiant festival, and our Lotte Lehmann was its brilliant center.” These few roles are only a sample of how much Schalk conducted Lehmann. The Chronology demonstrates far better. An Ariadne auf Naxos in Vienna in June 1931 turned out to be the last performance that she sang with her beloved Schalk. He died in 1931, and Lehmann walked behind his coffin to the cemetery. That evening, at the opera house, Clemens Krauss conducted Siegfried’s “Funeral March” before a memorial performance of Die Meistersinger in which Lehmann sang Eva. She recalls how deeply she was moved, in Midway in my Song: “In the last act the chorus, ‘Awake!’ [Wach’ auf!], recalled to my mind the familiar figure at the desk….I closed my eyes, and it was as if he were there again—surrendered to the waves of music: ‘Awake! The dawn of day draws near…’ An uncontrollable fit of weeping shook me, and my colleagues quickly formed a protecting wall round me so that no one might see my tears….” On 8 December 1931, there was a special concert in memory of Schalk. Two great orchestras, the chorus of the Vienna Opera, and many leading soloists were involved. Bruno Walter conducted and Lehmann sang Mahler’s “Um Mitternacht.”

William Steinberg (1899–1978) was a German-American conductor who began his career with the Cologne Opera, then the Frankfurt Opera. Because he was Jewish he was dismissed in 1933 and worked with orchestras in what is now Israel, where Toscanini heard him and hired him as his assistant for the NBC Symphony Orchestra. He also conducted the New York Philharmonic and Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, but is best remembered for his tenure with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (1956–1976). He conducted Lehmann in 1946, with the PSO and perhaps more.

Richard Strauss (1864–1949) was one of the most famous composers of his time, but less remembered as a conductor. He did conduct a lot! Whether that was because he was such a well-respected composer is difficult to determine. At the Vienna Opera he conducted many performances with Lehmann, and not just of his own operas. The operas began with Der Freischütz in 1920, and continued with Lohengrin, Magic Flute, Die Walküre, Der Barbier von Bagdad, Tannhäuser, Fidelio, and concert performances of his songs. Obviously, the majority of the operas that Lehmann sang with Strauss were his own, but sadly, we have no recordings of them.

George Szell (1897–1970) was a Hungarian-born American conductor, famous for his tenure as music director of the Cleveland Orchestra (1946–1970). Its present status as a world-class orchestra is due to his “orchestra building.” For Lehmann he conducted Lohengrin, Die tote Stadt, and Tosca at the Berlin Staatsoper in 1924, and in that same year, conducted the orchestra that accompanied Lehmann and Tauber in their famous recording of “Glück, das mir verblieb,” from Die tote Stadt, as well as other arias from Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, and Otello. In 1943 Szell conducted Tannhäuser at the Met with Lehmann as Elisabeth. In 1945 he led the Met orchestra when Lehmann sang her last appearances there as the Marschallin (broadcast and recorded).

Arturo Toscanini (1867–1957) was one of the most famous conductors of all time; he was renowned (and feared) for his intensity and perfectionism. His searching mind didn’t fear involvement with politics. Books have been written about him, so I will go directly to his relation with Lehmann. Relation is the right word. They were musical colleagues, friends, and lovers. Sadly, the only recorded evidence that we have of them working together is a shortwave broadcast that’s almost unlistenable. From their “radio broadcast” firsts in 1934 to their Salzburg Fidelios, the historic nature of their collaboration was evident to all listeners, whether critics or general public.

Alfred Wallenstein (1895–1983) was an American cellist and conductor. He played in such major orchestras as the San Francisco Symphony and the New York Philharmonic under Toscanini. He was music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic (1943–1956), and it was in this capacity that he directed the orchestra while Lehmann sang songs and arias in 1944. He had also conducted radio broadcasts with Lehmann in 1941 and 1942. These were both “America Preferred” War Bond promotional programs sponsored by the U.S. Treasury, in which Lehmann sang German songs and arias. I’ve always been amazed that such an event could occur while we were at war with Germany. It speaks highly for the U.S.

Bruno Walter (1876–1962) was one of Lehmann’s greatest sources of inspiration. From their first collaboration in 1924 (her first Marschallin) until her final recitals with him in 1950, Bruno Walter was her best friend, revered teacher, conductor, accompanist, and advisor. Walter held Lehmann in high esteem and chose to work with her. Their collaborations in the Salzburg Festivals, both in opera and in Lieder, set standards that were highly regarded by both public and critics. The number of collaborations is best seen by reading the Chronology.

Franz Waxman (1906–1967) was a German-American composer/conductor, probably best remembered for his Carmen Fantasy. He also wrote scores for many films, winning Oscars for two. His association with Lehmann was limited to one concert when he may have conducted at the Beverly Hills High School in 1947, for which Lehmann sang orchestrated songs and excerpts from Der Rosenkavalier.

Felix Weingartner (1863–1942) was a highly respected Austrian conductor/composer, who had studied with Liszt. After many successes in Germany, he succeeded Mahler at the Vienna Opera in 1908 and continued (off and on) in Vienna until 1927, conducting, teaching, and composing thereafter. He conducted Lehmann beginning in 1918 with a Vienna Philharmonic performance of Lieder arranged for orchestra, and continuing in Vienna with opera, the 1922 South American tour, and further in 1927 with a celebrated Meistersinger in Vienna. In 1933 he led the orchestra when Lehmann sang a cycle of his own songs called An den Schmerz.Abravanel was at the Met at the end of Lehmann’s career and conducted her many times there. He went on to become a strong force at the Music Academy of the West (1954 – 1980) and worked well with Lehmann there. I (Gary Hickling) had the privilege of playing bass under his baton for three summers at the MAW. His major fame, however, comes from the fact that he brought the Salt Lake Symphony (Utah) to a high degree of polish. He conducted there for 32 years!

Leo Blech (1871 – 1958) was in his time one of the most famous conductors, though he also was a composer. He conducted in Berlin at the Königliches Schauspielhaus (later the Berlin State Opera or Staatsoper unter den Linden). It is there that he conducted Lehmann in Wagner and Strauss roles. One of Lehmann’s favorite encores, especially early in her recital career, was his “Heimkehr vom Fest.”

Artur Bodanzky (1877 – 1939) was the Metropolitan Opera major Wagner “house conductor” from 1915 until his death. Not really known outside of his work for the Met, and not highly respected, the surviving recordings made from the live Saturday radio broadcasts, show a real command of the scores. He conducted Lehmann at the Met in many of her Wagner appearances (more than any other conductor there).

Fritz Busch (1890 – 1951) conducted most famously (in Germany) in Dresden, where he led Lehmann in the world premier of Intermezzo by Strauss in 1924. After 1933, because of his outspoken opposition to the Nazis, he conducted in South America, Scandinavia and England (Glyndebourne Festival Opera). He had lots of family connections in the classical music world, being the brother of violinist Adolf Busch (who was especially famous for founding the Busch Quartet, and for playing with Rudolf Serkin, who married his daughter) and brother of cellist Hermann Busch.

Antol Doráti (1906 – 1988) the great Hungarian-born conductor (and composer) who, after studying with Bartok, was able to conduct the world premier of his viola concerto with his Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, where he conducted for 11 years. He conducted other American and European orchestras as well. He only conducted one Lehmann concert, and that was with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in 1939.

Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886 – 1954) was one of the most respected German conductors of his time. But because he stayed in Germany during the Nazi period, his reputation, especially in the US, was badly tarnished. Possibly because of the Nazi association, Lehmann didn’t speak of him in her interviews, but she sang under his direction many times, including concerts, as well as operas in Berlin, Paris, and Vienna.

Robert Heger (1886 – 1978) was not a famous conductor outside of Europe. His principle claim to fame was the recording of Der Rosenkavalier that he made with Lehmann, Schumann, et al. He conducted Lehmann many times at Covent Garden, but was most conspicuous in her life at the Vienna Opera. Lehmann probably sang more under his baton, than any other single conductor (82 performances!). He was also a composer and wrote a cycle of songs to Lehmann poems. His Nazi associations hurt his post war years.

Robert Heger (1886 – 1978) was not a famous conductor outside of Europe. His principle claim to fame was the recording of Der Rosenkavalier that he made with Lehmann, Schumann, et al. He conducted Lehmann many times at Covent Garden, but was most conspicuous in her life at the Vienna Opera. Lehmann probably sang more under his baton, than any other single conductor (82 performances!). He was also a composer and wrote a cycle of songs to Lehmann poems. His Nazi associations hurt his post war years.

José Iturbi (1895 – 1980) was a Spanish conductor, harpsichordist and pianist. Famous from his appearances in Hollywood films of the 1940’s, he first conducted Lehmann in 1937 on the Ford Sunday Evening Hour and in 1938 when he was the conductor of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra.

Erich Kleiber (1890 – 1956), one of the great conductors of the 20th century, he had only limited contact with Lehmann. In 1932, he conducted her as Sieglinde for the Berlin Sate Opera. In a 1938 Covent Garden performance of Der Rosenkavalier, during the first lines of the Marschallin’s monologue in the first act, Lehmann felt faint and stopped singing. So he didn’t conduct much of her performance!

Erich Kleiber (1890 – 1956), one of the great conductors of the 20th century, he had only limited contact with Lehmann. In 1932, he conducted her as Sieglinde for the Berlin Sate Opera. In a 1938 Covent Garden performance of Der Rosenkavalier, during the first lines of the Marschallin’s monologue in the first act, Lehmann felt faint and stopped singing. So he didn’t conduct much of her performance!

Otto Klemperer (1885 – 1973) was an important German conductor who, despite his psychological problems, worked successfully with orchestras in both Europe and the US. He had begun his work with the Hamburg opera the same year Lehmann did and conducted her first big success there as Elsa in Lohengrin. He held many positions in his life, but the ones that mattered for Lehmann were his time at the Kroll Opera in Berlin (1927 – 1931) and the Los Angeles Philharmonic (as late as 1944 in the Hollywood Bowl). As a guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic, he conducted Lehmann at Carnegie Hall. His fascinating career is certainly worth reading, but covers much more than this web-page can.

Hans Knappertsbusch (1888 – 1965) was a highly respected German conductor, especially well-known for his Wagner and Richard Strauss interpretations. He had problems with the Nazis and left Germany to conduct at the Vienna Opera, where he paced many Lehmann appearances. In 1937 he conducted a Rosenkavalier performance with Lehmann at the Salzburg Festival. Before those appearances, as early at 1926 he had conducted her Eva in Die Meistersinger in Munich.

Erich Korngold (1897 – 1957) was a wunderkind composer of operas. Though Lehmann sang in several of his operas, he only conducted her in his Der Ring des Polykrates in 1919 and 1920 (at the age of 23!). Korngold is best known for his film music composed in Hollywood from the 1930s and 1940s.

Serge Koussevitzky (1874 – 1951) a Russian-born conductor (and for me [Gary Hickling] famous as a composer/bassist!), Koussevitzky is remembered mostly for conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1924 until 1949. During that time, he made significant recordings with the orchestra and commissioned many works including Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G, Gershwin’s Second Rhapsody, Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 4, Hindemith’s Concert Music for Strings and Brass, Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra and many others. Not an important conductor in Lehmann’s career, he did conduct her in two concert performances in 1935 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Clemens Krauss (1893 – 1954) was a highly respected Austrian conductor, associated both professionally and personally with Richard Strauss. He became the director of the Vienna State Opera in 1929 and was also connected with the Salzburg Festival. He conducted Lehmann many times in both these venues, (as early as 1922), but because his mistress and later second wife, Viorica Ursuleac, sang many “Lehmann” roles he, of course, tried to engage Ursuleac. This caused great friction between him and Lehmann, as can be seen in this Salzburg Festival photo.

Josef Krips (1902 – 1974) was an Austrian conductor. He studied with Weingartner (see below) and became his assistant at the Vienna Volksoper. He conducted orchestras such as Karlsruhe, but was most active in Vienna until the Anschluss. He returned to Vienna after the war and also conducted the London and San Francisco Symphony orchestras, as well as leading operas at the Met, Covent Garden and Berlin. Krips was not extremely important in Lehmann’s career, having conducted her (mostly in Der Rosenkavalier) at the Vienna Opera in 16 performances in 1933, 34, 35, and 37.

Erich Leinsdorf (1912 – 1993) was born in Vienna, studied conducting at the Mozarteum in Salzburg and later in Vienna. From 1934 – 1937 he assisted Bruno Walter and Arturo Toscanini at the Salzburg Festival. In 1937 he began as an assistant conductor at the Met and since the Nazis took over Austria shortly thereafter, he remained in the US. After Bodanzky’s death in 1939, Leinsdorf took over the German repertoire at the Met. From 1947 – 1955 he led the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, and from 1962 – 1969 he was music director for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. After that he guest conducted. He conducted at least 30 performances at the Met that included Lehmann. It is said that Lehmann recommended him.

Erich Leinsdorf (1912 – 1993) was born in Vienna, studied conducting at the Mozarteum in Salzburg and later in Vienna. From 1934 – 1937 he assisted Bruno Walter and Arturo Toscanini at the Salzburg Festival. In 1937 he began as an assistant conductor at the Met and since the Nazis took over Austria shortly thereafter, he remained in the US. After Bodanzky’s death in 1939, Leinsdorf took over the German repertoire at the Met. From 1947 – 1955 he led the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, and from 1962 – 1969 he was music director for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. After that he guest conducted. He conducted at least 30 performances at the Met that included Lehmann. It is said that Lehmann recommended him.

Charles Münch (1891 – 1968) was an Alsatian conductor, specializing in the French repertoire and highly respected for his time (1949 – 1962) as the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He led the Lamoureux Orchestra at the Salle Gaveau, in Paris for one performance that included Lehmann ( in which she sang Beethoven and Wagner arias).

Dimitri Mitropoulus (1896 – 1960) was a Greek conductor, pianist and composer. From 1937 – 1949 served at the principal conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, thereafter working with the New York Philharmonic until his protégé Leonard Bernstein succeeded him in 1958. He conducted as well as accompanied Lehmann in Athens, Greece, and conducted her for a concert at La Scala, Milan (both of these in the 1930s).

Pierre Monteux (1875 – 1964) was a renowned orchestra conductor who began in Paris as a violist, playing under Nikisch, Mahler and Richard Strauss. He became famous for conducting the Ballets Russes between 1911 – 1914 in Stravinsky’s Petrushka, The Rite of Spring; Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé and Debussy’s Jeux. He conducted at the Met, and symphony orchestras in Boston (1919 – 24), Amsterdam (1921 -34), and San Francisco (1936 -1952). His students include Neville Marriner, André Previn, Lorin Maazel and Seji Ozawa. He conducted Lehmann twice: in 1929 in Amsterdam and in 1936 with the Orchestre symphonique de Paris.

Arthur Nikisch (1855 – 1922) was considered the preeminent composer of his time. Although Hungarian, he worked internationally, holding posts in Boston, London and Berlin. He was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra from 1895 until his death. He conducted Lehmann about eight times at the Hamburg Opera in 1915 and 1916.

Eugene Ormandy (1899 – 1985) Hungarian-born conductor. Though he conducted the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, his fame rests primarily on his 44 year tenure with the Philadelphia Orchestra. The many recordings he made there have made certain his fame for all time. In 1934, while still in Minneapolis, he conducted Lehmann in arias and songs. In 1948 Ormandy conducted the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra while Lehmann sang Strauss songs.

Eugene Ormandy (1899 – 1985) Hungarian-born conductor. Though he conducted the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, his fame rests primarily on his 44 year tenure with the Philadelphia Orchestra. The many recordings he made there have made certain his fame for all time. In 1934, while still in Minneapolis, he conducted Lehmann in arias and songs. In 1948 Ormandy conducted the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra while Lehmann sang Strauss songs.

Paul Paray (1886 – 1979) was a French conductor best remembered for his tenure for more than a decade with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. He conducted Lehmann in Monte Carlo in 1929 and 1931.

Fritz Reiner (1888 – 1963) was a prominent conductor of both opera and symphonic music. The pinnacle of his career was his work in the 1950s and 1960s with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra with which he made many recordings. He’d studied in Budapest with Bartok, worked with Richard Strauss in Dresden and became Principal Conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra in 1922. He conducted the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra from 1938 – 1948. With Lehmann, he led a Rosenkavalier with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1934, and a famous 1936 San Francisco Opera performance of Die Walküre with the all-star cast of Melchior, List, Schorr and Flagstad as Brünnhilde. This was partially recorded.

Artur Rodzinski (1892 – 1958) was a Polish conductor of opera and symphonic music. His time with the Cleveland Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic in the 1930s and 1940s are especially important. He conducted Lehmann as the Marschallin with the Cleveland Orchestra in 1935 and in concert with the New York Philharmonic in 1937.

Victor de Sabata (1892 – 1967) was an Italian conductor, specializing in Verdi, Puccini and Wagner. He is renowned for his many years at Milan’s La Scala (starting in 1921) where he succeeded Toscanini, with whom he is often favorably compared. He conducted some of Lehmann’s appearances as Desdemona at the Vienna Opera in 1935 and 1936.

Franz Schalk (1863 – 1931) was an Austrian conductor, best known for his association with the Vienna Opera. He actually studied with Anton Bruckner! His association with Lotte Lehmann was profound. Schalk gave Vienna the local première of Pfitzner’s Palestrina, with Lehmann was cast as Silla and Die Frau ohne Schatten by R. Strauss, with Lehmann as the Dyer’s Wife. Especially for Lehmann, Schalk revived the title of Kammersängerin (literally “Chamber Singer,” from the days of the monarchy when singers were honored by the appointment to sing for the emperor in his chamber, a sign of his highest esteem). She was the first singer to receive that designation since the collapse of the monarchy. She officially became Frau Kammersängerin Lotte Lehmann on February 17, 1926. For the Beethoven Centennial in 1927 Schalk conducted as Lehmann sang her first Leonores. He wrote: “A great, overwhelming, radiant festival, and our Lotte Lehmann was its brilliant center.” These few roles are only a sample of how much Schalk conducted Lehmann. The chronology demonstrates far better. An Ariadne auf Naxos in Vienna in June 1931 turned out to be the last performance that she sang with her beloved Schalk, who was failing fast ever since he lost the directorship of the Vienna Opera. He died on September 3, 1931, and Lotte walked behind his coffin to the cemetery. That evening, at the opera house, Clemens Krauss conducted Siegfried’s Funeral March before a memorial performance of Die Meistersinger. Lotte was the Eva. She recalls how deeply she was moved, in Midway in my Song: ‘In the last act the chorus, “Awake!” [“Wach’ auf!“], recalled to my mind the familiar figure at the desk….I closed my eyes, and it was as if he were there again—surrendered to the waves of music: “Awake! The dawn of day draws near….” An uncontrollable fit of weeping shook me, and my colleagues quickly formed a protecting wall round me so that no one might see my tears…. ‘ On December 8, 1931, there was a special concert in memory of Schalk. Two great orchestras, the chorus of the Vienna Opera, and many leading soloists were involved. Bruno Walter conducted and Lehmann sang Mahler’s Um Mitternacht.

Franz Schalk (1863 – 1931) was an Austrian conductor, best known for his association with the Vienna Opera. He actually studied with Anton Bruckner! His association with Lotte Lehmann was profound. Schalk gave Vienna the local première of Pfitzner’s Palestrina, with Lehmann was cast as Silla and Die Frau ohne Schatten by R. Strauss, with Lehmann as the Dyer’s Wife. Especially for Lehmann, Schalk revived the title of Kammersängerin (literally “Chamber Singer,” from the days of the monarchy when singers were honored by the appointment to sing for the emperor in his chamber, a sign of his highest esteem). She was the first singer to receive that designation since the collapse of the monarchy. She officially became Frau Kammersängerin Lotte Lehmann on February 17, 1926. For the Beethoven Centennial in 1927 Schalk conducted as Lehmann sang her first Leonores. He wrote: “A great, overwhelming, radiant festival, and our Lotte Lehmann was its brilliant center.” These few roles are only a sample of how much Schalk conducted Lehmann. The chronology demonstrates far better. An Ariadne auf Naxos in Vienna in June 1931 turned out to be the last performance that she sang with her beloved Schalk, who was failing fast ever since he lost the directorship of the Vienna Opera. He died on September 3, 1931, and Lotte walked behind his coffin to the cemetery. That evening, at the opera house, Clemens Krauss conducted Siegfried’s Funeral March before a memorial performance of Die Meistersinger. Lotte was the Eva. She recalls how deeply she was moved, in Midway in my Song: ‘In the last act the chorus, “Awake!” [“Wach’ auf!“], recalled to my mind the familiar figure at the desk….I closed my eyes, and it was as if he were there again—surrendered to the waves of music: “Awake! The dawn of day draws near….” An uncontrollable fit of weeping shook me, and my colleagues quickly formed a protecting wall round me so that no one might see my tears…. ‘ On December 8, 1931, there was a special concert in memory of Schalk. Two great orchestras, the chorus of the Vienna Opera, and many leading soloists were involved. Bruno Walter conducted and Lehmann sang Mahler’s Um Mitternacht.

William Steinberg (1899 – 1978) was a German-American conductor who began his career with the Cologne Opera, then Frankfurt Opera, but because he was Jewish, was dismissed in 1933 and worked with orchestras in what is now Israel, where Toscanini heard him and hired him as his assistant for the NBC Symphony Orchestra. He also conducted the New York Philharmonic, and Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, but is best remembered for his tenure (1956 – 1976) with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. He conducted Lehmann only once, (1946) with the PSO.

Leopold Stokowski (1882 – 1977) British conductor, best known for his many years with the Philadelphia Orchestra, though he had success with the orchestras of Cincinnati, New York, Houston and Hollywood Bowl. Not a significant conductor in Lehmann’s life, she was scheduled to sing with him and the Philadelphia Orchestra during the 1934 – 1935 season, but there is no evidence that this concert actually took place.

Richard Strauss (1864 – 1949) was one of the most famous composers of his time, but less remembered as a conductor. But he did conduct a lot! Whether that was because he was such a well-respected composer is difficult to determine. At the Vienna Opera he conducted many performances with Lehmann, and not just of his own operas. Starting with Der Freischütz in 1920, and continuing with Lohengrin, Magic Flute, Die Walküre, Der Barbier von Bagdad, Tannhäuser, Fidelio, and in concert performances of his songs. Obviously, the majority of the operas that Lehmann sang with Strauss were his own, but sadly, we have no recordings of them.

of his time, but less remembered as a conductor. But he did conduct a lot! Whether that was because he was such a well-respected composer is difficult to determine. At the Vienna Opera he conducted many performances with Lehmann, and not just of his own operas. Starting with Der Freischütz in 1920, and continuing with Lohengrin, Magic Flute, Die Walküre, Der Barbier von Bagdad, Tannhäuser, Fidelio, and in concert performances of his songs. Obviously, the majority of the operas that Lehmann sang with Strauss were his own, but sadly, we have no recordings of them.

George Szell (1897 – 1970) was a Hungarian-born American conductor, famous for his tenure (1946 – 1970) as music director of the Cleveland Orchestra. Its present status as a world-class orchestra is due to his “orchestra building.” For Lehmann he conducted Lohengrin, Die tote Stadt and Tosca at the Berlin Staatsoper in 1924, and in that same year, conducted the orchestra that accompanied Lehmann and Tauber in their famous recording of “Glück, das mir verblieb”, from Die tote Stadt, as well as other arias from Tannhäuser, Lohengrin and Otello. In 1943 Szell conducted Tannhäuser at the Met with Lehmann as Elisabeth. In 1945 he led the Met orchestra when Lehmann sang her last appearances there as the Marschallin (broadcast and recorded).

Arturo Toscanini (1867 – 1957) was one of the most famous conductors of all time. Renowned (and feared) for his intensity, perfectionism and detail, his searching mind didn’t fear involvement with politics. Books have been written about him, so I will not insult his memory with the few words I have, but go directly to his relation with Lehmann. And relation is the right word. They were musical colleagues, friends and lovers. Sadly, the only recorded evidence that we have of them working together is a shortwave broadcast that’s almost unlistenable. From their “radio broadcast” firsts in 1934 to their Salzburg Fidelios the historic nature of their collaboration was evident to all listeners, whether critics or general public.

Arturo Toscanini (1867 – 1957) was one of the most famous conductors of all time. Renowned (and feared) for his intensity, perfectionism and detail, his searching mind didn’t fear involvement with politics. Books have been written about him, so I will not insult his memory with the few words I have, but go directly to his relation with Lehmann. And relation is the right word. They were musical colleagues, friends and lovers. Sadly, the only recorded evidence that we have of them working together is a shortwave broadcast that’s almost unlistenable. From their “radio broadcast” firsts in 1934 to their Salzburg Fidelios the historic nature of their collaboration was evident to all listeners, whether critics or general public.

Alfred Wallenstein (1895 – 1983) was an American cellist and conductor. He played in such major orchestras as the San Francisco Symphony and the New York Philharmonic under Toscanini. From 1943 – 1956 he was music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and it was in this capacity that he directed the orchestra while Lehmann sang songs and arias in 1944. He had also conducted radio broadcasts with Lehmann in 1941 and 1942. These were both “America Preferred” War Bond promotional programs sponsored by the US Treasury, in which Lehmann sang German songs and arias. I’ve always been amazed that such an event could occur while we were at war with Germany. It speaks highly for the US.

Bruno Walter (1876 – 1962) was one of Lehmann’s greatest sources of inspiration. From their first collaboration in 1924 (her first Marschallin) until her final recitals with him in 1950, Bruno Walter was her best friend, revered teacher, conductor, accompanist, and advisor. Walter held Mme. Lehmann in high esteem and chose to work with her. Their collaborations in the Salzburg Festivals both in opera and in Lieder, set standards that were highly regarded by both public and critics. The number of collaborations is best seen by going to the Chronology. And for more information on Bruno Walter, here’s a link.

of inspiration. From their first collaboration in 1924 (her first Marschallin) until her final recitals with him in 1950, Bruno Walter was her best friend, revered teacher, conductor, accompanist, and advisor. Walter held Mme. Lehmann in high esteem and chose to work with her. Their collaborations in the Salzburg Festivals both in opera and in Lieder, set standards that were highly regarded by both public and critics. The number of collaborations is best seen by going to the Chronology. And for more information on Bruno Walter, here’s a link.

Franz Waxman (1906 -1967) was a German-American composer/conductor, probably best remembered for his Carmen Fantasy. He also wrote scores for many films, winning Oscars for two. His association with Lehmann was limited to one concert when he conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Beverly Hills High School in 1947, for which Lehmann sang orchestrated songs and excerpts from Der Rosenkavalier.

Felix Weingartner (1863 – 1942) was a highly respected Austrian conductor and composer, who had studied with Liszt. After many successes in Germany, he succeeded Mahler at the Vienna Opera in 1908 and continued (off and on) in Vienna until 1927, conducting, teaching and composing thereafter. Beginning in 1918 with a Vienna Philharmonic performance of Lieder arranged for orchestra, and continuing in Vienna with opera, the 1922 South American tour and further in 1927 with a celebrated Meistersinger in Vienna, Weingartner conducted Lehmann in many concert and Wagner opera performances. In 1933 he led the orchestra when Lehmann sang a cycle of his own songs called An den Schmerz.