Legendary: The most feared and revered conductor of the 20th century, Arturo Toscanini, called Lotte Lehmann “the greatest artist in the world.” One of the early 20th century’s really successful composers, Richard Strauss, uttered the words that are now engraved on her tombstone: Sie hat gesungen, dass es Sterne rührte—her singing moved the stars. Giacomo Puccini, the opera composer of her time, preferred her “soavissima” Suor Angelica to all others.

Unknown: Nowadays most people have no idea who Lotte Lehmann was. This presentation examines the legacy of Lotte Lehmann, who, during her opera career’s zenith from the 1920s to the 1940s, was considered the most significant singing actress to be heard on stage or on recordings. Her Lieder career overlapped her opera life and continued until 1951.

Finally, Lehmann taught, with more claim to success on that account than any other celebrated singer. The section called “Lehmann Teaches” covers Lehmann the teacher; this one is devoted to her singing, both opera and Lieder, with recorded examples.

Fortunately for those interested in Lehmann’s singing art, she made many recordings. Although some of the recording techniques available at the time were primitive, her ability to project what she was singing—expressively and emotionally, even in a recording studio—can make a listener feel the music almost viscerally.

Even so, many fans insisted that what we can hear from recordings are dull, lifeless representations, as compared to experiencing Lehmann’s live performances. Those of us who never saw her on stage are nonetheless thrilled with what we hear in recordings. She projected the poetry or libretto with complete authority and emotional involvement. But the way she moved, her facial expressions, and her hands were all said to have been as expressive as her singing. Your Eyes Don’t Sing

And that brings us to an examination of her voice. In her prime it could be so sweet, so beautiful, so gracious, and genial that we forget to pay attention to the words. Just listen to Lehmann’s creamy sound of this 1928 recording of “Mit deinen blauen Augen” (With your Blue Eyes) by Richard Strauss. The “118” relates to the number found in the Discography. 118 Mit seinen blauen Augen

Sometimes we do need to understand the words or situation to revel in her fervor, her complete identification with the moment or the character’s feeling. Lehmann’s emotional voice in this 1935 recording can sound almost silly if we don’t know that Sieglinde has been separated from Siegmund and is desperate to warn him in this scene from Wagner’s Die Walküre. 244 Horch, O Horch! Das Is Hundings Horn!

| Listen, Oh listen! That’s Hunding’s horn. His gangs are coming fully armed. No sword will serve when their dogs attack. Throw it away, Siegmund. Siegmund, where are you? Ah, there—I see you— Horrible sight! The dogs are gnashing their teeth at your flesh; they don’t respect your noble features; they fasten their firm teeth on your leg, you fall, your sword shatters in pieces. The tree topples, the trunk breaks. Brother, my brother, Siegmund—Ah! |

As she aged, her voice lost some of its sheen, luster, and grace. But especially in the Lieder recordings and radio broadcasts made from 1935 through 1949 we can still hear the way Lehmann could color a word, or add allure or charm to a phrase by her piquant changes in tempo or the suggestive use of portamento to be sly or impish. Listen to this in this Mozart song of young impetuous love called “Die Verschweigung” (Concealment). 248 Die Verschweigung

Partly because one of her teachers forced her to sing over and over the legato aria “Dove sono” from Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, and in some measure because she heard how singers of the latter half of the twentieth century consciously used “performance practice,” she wasn’t pleased with her Mozart recordings. I had planned to play some of her Mozart arias for her 85th birthday tribute, until Lehmann stopped me. In My Many Lives, Lehmann wrote about never finding her way to Mozart’s “ethereal language of the heart,” suggesting that she may have “always been too earthbound in my feeling.” “…I feel that in singing Mozart, emotion should be expressed just as warmly and glowingly as in other operas. It only wears a more supple cloak.…” One can compare this 1927 recording Lehmann made of “Heil’ge Quelle” with an excerpt from a 2008 performance of Véronique Gens in the same aria originally called “Porgi Amor.”106 Heil’ge Quelle reiner Treibe Porgi Amor

The Legendary Lehmann: Elsa in Lohengrin You can find the list of Lotte Lehmann’s “Opera Roles” on this site, under Documentation. It is impressive for both the number and the variety. She sang a lot of small roles at the beginning of her career as well as many of the greatest opera roles that a lyric soprano can essay. In spite of learning and performing more than 90 roles, the fabled aspect of Lehmann’s opera career is no doubt based on her performances of a few that she made her own and that became identified with her: Beethoven’s Fidelio; her Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier of Richard Strauss; and the Wagner roles of Elsa in Lohengrin, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, and above all, Sieglinde in Die Walküre.

Though Lehmann herself did call Elsa something of a “silly goose”* you wouldn’t know it from the bold commitment we hear when she sings of her complete faith that a knight in shining armor will appear to be her champion. *because Elsa asks Lohengrin the question that she’s been forbidden to ask.

Lehmann wrote in her book My Many Lives that “…Elsa is represented as so lost in her dream that she seems to lose any personality which she might have, in a sickly sweetness.” Obviously, this is not how Lehmann interpreted the role.

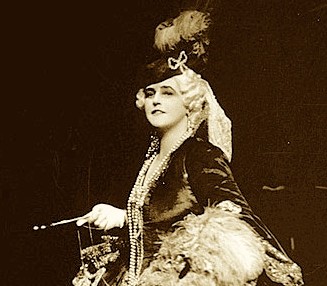

In Hamburg on the night of 29 November 1912, after only two years with the company. Lehmann made her debut as Elsa, a demanding leading role that demonstrated her acting and emotive singing ability. Her strong success as Elsa established her position at the Hamburg Opera so that she was regularly offered major roles from then on. In this rare early photo of Lehmann as Elsa one can observe the devotion and concentration that one also hears in every Lohengrin recording she made. Einsam in trüben Tagen

| Einsam in trüben Tagen hab ich zu Gott gefleht, des Herzens tiefstes Klagen ergoss ich im Gebet. Da drang aus meinem Stöhnen ein Laut so klagevoll, der zu gewalt’gem Tönen weit in die Lüfte schwoll: Ich hört ihn fernhin hallen, bis kaum mein Ohr er traf; mein Aug ist zugefallen, ich sank in süssen Schlaf. In Lichter Waffen Scheine ein Ritter nahte da, so tugendlicher Reine ich keinen noch ersah: Ein golden Horn zur Hüften, gelehnet auf sein Schwert, – so trat er aus den Lüften zu mir, der Recke wert; mit züchtigem Gebaren gab Tröstung er mir ein; – des Ritters will ich wahren, er soll mein Streiter sein! | Lonely, in troubled days I prayed to the Lord, my most heartfelt grief I poured out in prayer. And from my groans there issued a plaintive sound that grew into a mighteous roar as it echoed through the skies: I listened as it receded into the distance until my ear could scarce hear it; my eyes closed and I fell into a deep sleep. In splendid, shining armor a knight approached, a man of such pure virtue as I had never seen before: a golden horn at his side, leaning on a sword – thus he appeared to me from nowhere, this warrior true; with kindly gestures he gave me comfort; I will wait for the knight, he shall be my champion! |

Elisabeth in Tannhäuser. Lehmann often spoke of her portrayal of Elisabeth with great satisfaction. In My Many Lives she wrote that “…to be able to portray Elisabeth, suffering, the greatest teacher, must have sung its painful and somber melody…one cannot represent great emotions if one has not experienced them deeply oneself.” At this point of the opera, however, as Elisabeth enters, we can hear the sheer joy in her voice as she greets the hall of song anticipating Tannhäuser’s return. This 1930 performance of “Dich teure Halle” (You Dear Hall) is almost iconic in Lehmann’s recorded legacy. 169 Dich teure Halle

| Dich, teure Halle, grüss ich wieder, froh grüss ich dich, geliebter Raum! In dir erwachen seine Lieder und wecken mich aus düstrem Traum. Da er aus dir geschieden, wie öd’ erschienst du mir! Aus mir entfloh der Frieden, die Freude zog aus dir. Wie jetzt mein Busen hoch sich hebet, so scheinst du jetzt mir stolz und hehr. Der mich und dich so neu belebet, nicht weilt er ferne mehr, Du teure Halle, sei mir gegrüßt! | Dear hall, I greet you once again, joyfully I greet you, beloved place! In you his songs awake and waken me from gloomy dreams. When he departed from you, how desolate you appeared to me! Peace forsook me, joy took leave of you. How strongly now my heart is leaping; to me now you appear exalted & sublime. He who thus revives both me and you, tarries afar no more. You dear hall, I greet thee! |

Sieglinde in Die Walküre. Lehmann found something deeply human in Sieglinde’s predicament: falling in love with her twin brother didn’t suggest anything less than complete devotion. This 1935 recording has maintained its status as one of the great “recordings of the century.” “Du bist der Lenz” (You are Spring) is one of the few arias in Die Walküre and as such many sopranos sing it, even on recital programs. The story is too long to give even a general idea, so follow the words and they will tell you enough for this aria’s meaning. In My Many Lives, Lehmann tells us that Sieglinde is the surely “…the nearest to our feeling…she is close to the earth and humanly convincing.” Sieglinde gradually recognizes in Siegmund all that her life lacks.

Du bist der Lenz (Die Walküre, Act 1)

| Du bist der Lenz, nach dem ich verlangte in frostigen Winters Frist. Dich grüßte mein Herz mit heiligem Grau’n, als dein Blick zuerst mir erblühte. Fremdes nur sah ich von je, freudlos war mir das Nahe. Als hätt’ ich nie es gekannt, war, was immer mir kam. Doch dich kannt’ ich deutlich und klar: als mein Auge dich sah, warst du mein Eigen; was im Busen ich barg, was ich bin, hell wie der Tag taucht’ es mir auf, o wie tönender Schall schlug’s an mein Ohr, als in frostig öder Fremde zuerst ich den Freund ersah. | You are the Spring for which I longed in the frosty winter season. My heart greeted you with holy terror when your first glance set me on fire. I had only ever seen strangers; my surroundings were friendless. As if I had never known, that was everything that came my way. But I recognized you plain and clear; when my eyes saw you, you were mine; what I hid in my heart, what I am, bright as day it came to me, like a resounding echo it fell upon my ear, when cold, lonely and estranged I first saw my friend. |

Leonore/Fidelio in Fidelio. Perhaps it’s strange to associate someone as feminine as Lehmann with the trouser role of Fidelio, but remember she’s Leonore dressed up as a young man, in order to infiltrate the prison and free her husband. This 1927 recording was made during the same year that she took on this dramatically and vocally demanding role for the centenary year of Beethoven’s death. She continued to sing Fidelio with extraordinary success in Vienna and all over Europe. You’ll find an interleaved commentary of this aria in the proposed section called Arias and Lieder. “I found [in the role of Leonore] the most exalted moments of my opera career and was shaken by it to the depths of my being.” 103 Komm, Hoffnung

| Komm, Hoffnung, lass den letzten Stern Der Müden nicht erbleichen! Erhell mein Ziel, sei’s noch so fern, Die Liebe wird’s erreichen. Ich folg’ dem innern Triebe, Ich wanke nicht, Mich stärkt die Pflicht Der treuen Gattenliebe! O du, für den ich alles trug, Könnt’ ich zur Stelle dringen, Wo Bosheit dich in Fesseln schlug, Und süssen Trost dir bringen! | Come, hope, let the last star Not fade from fatigue! Illumine my goal, even if it’s far, Love will reach it. I follow an inner drive, I will not waver, True marital love Strengthens my duty! O you, for whom I bore everything, If only I could be at your side, Where evil has you bound, And bring you sweet comfort! |

The Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier. History will certainly remember Lotte Lehmann best as the Marschallin. In his book Theme and Variations, Bruno Walter wrote,

…as for Lotte Lehmann’s work as the Marschallin, it was even then [1924] surrounded by the brilliance which has made her portrayal of that part one of the outstanding achievements on the contemporary operatic stage. Here, indeed, was that rare phenomenon of an artist’s personality wholly merged with a poetic figure, and of a transitory theatrical event being turned into an unforgettable experience.

In 1935 Lehmann made the definitive recording of a portion of the role of the Marschallin. The Vienna Philharmonic was conducted by Robert Heger. We have a portion of the first act monologue for which she became so famous. Listen for the speech-like quality with which Lehmann is able to sing this. Kann mich

| Da geht er hin, der aufgeblasne schlechte Kerl, und kriegt das hübsche junge Ding und einen Pinkel Geld dazu. Als müsst’s so sein. Und bildet sich noch ein, dass er es ist, der sich was vergibt. Was erzürn’ich mich denn? ‘s ist doch der Lauf der Welt. Kann mich auch an ein Mädel erinnern, die frisch aus dem Kloster ist in den heiligen Ehestand kommandiert word’n. Wo ist die jetzt? Ja, such’ dir den Schnee vom vergangenen Jahr! Das sag’ ich so: Aber wie kann das wirklich sein, dass ich die kleine Resi war und dass ich auch einmal die alte Frau sein werd’. Die alte Frau, die alte Marschallin! “Siegst es, da geht’s die alte Fürstin Resi!” Wie kann denn das geschehen? Wie macht denn das der liebe Gott? Wo ich doch immer die gleiche bin. Und wenn er’s schon so machen muss, warum lasst er mich denn zuschaun dabei mit gar so klarem Sinn! Warum versteckt er’s nicht vor mir? Das alles ist geheim, so viel geheim. Und man ist dazu da, dass man’s ertragt. Und in dem “Wie” da liegt der ganze Unterschied | There he goes, the bloated worthless fellow, And gets the pretty young thing and a tidy fortune too, As if it had to be. And flatters himself that is he who makes the sacrifice. But why do I upset myself? It’s just the way of the world. I well remember a girl Who came fresh from the convent to be forced into holy matrimony. Where is she now? Yes, seek the snows of yesteryear! This is what I say: But can it really be, That I was that young Resi And shall one day become the old woman… The old woman, the Fieldmarshal’s wife! “Look you, there goes the old Princess Resi!” How can it come to pass? How does the dear Lord do it? While I always remain the same. And if He has to do it like this, Why does He let me watch it happen, With such clear sense? Why doesn’t He hide it from me? It is all a mystery, so deep a mystery, And one is here to endure it. And in the “how” There lies the whole difference. |

Legendary Lieder Lehmann’s Lieder career was as celebrated as her opera career. She took time to devote herself to the study necessary to develop this delicate art. Ferdinand Foll, who had known Hugo Wolf, became an early mentor. Bruno Walter and even Lehmann’s own brother Fritz, contributed to her growth in this demanding field. As Dalton Baldwin, the famous pianist for Gérard Souzay, said, the Lieder singer is naked out there. There are no costumes, no props, no sets, and no other characters on stage. The focus is solely on the singer and the pianist—and in the end, on the words of the poetry. At first, Lehmann sang with a little book of the poems, but Bruno Walter suggested that this broke the direct connection to the audience; she agreed and without the book, she found that she could give more attention to her hands, thus better supporting visually the varied emotions of the Lied. We’ve selected one representative song that Lehmann sang from each of the major Lieder composers. And that brings us to one of her most-performed Mozart songs, “Das Veilchen” (the Little Violet) to the words of Goethe. Here’s a little story of the unnoticed little violet that Lehmann delights in telling. 357 Das Veilchen

| Ein Veilchen auf der Wiese stand, Gebückt in sich und unbekannt; Es war ein herzigs Veilchen. Da kam ein’ junge Schäferin Mit leichtem Schritt und muntrem Sinn Daher, daher, Die Wiese her, und sang. Ach! denkt das Veilchen, wär ich nur Die schönste Blume der Natur, Ach, nur ein kleines Weilchen, Bis mich das Liebchen abgepflückt Und an dem Busen matt gedrückt! Ach nur, ach nur Ein Viertelstündchen lang! Ach! aber ach! das Mädchen kam Und nicht in Acht das Veilchen nahm, Ertrat das arme Veilchen. Es sank und starb und freut’ sich noch: Und sterb’ ich denn, so sterb’ ich doch Durch sie, durch sie, Zu ihren Füßen doch. | A violet grew on the meadow, Hunched over and unnoticed; It was a sweet violet. Along came a young shepherdess Lightly stepping, contentedly Along, along, The meadow, and sang. Ah! thinks the violet, if I were only Nature’s fairest flower, For just a little while, Until the darling picks me And presses me to her breast! Ah, only for A quarter hour long!Ah! but alas! The girl came by And didn’t notice the violet, Stepped on the poor violet. It sank and died, yet happy: And though I die, I shall have died Through her, through her, And at her feet. |

Moving chronologically brings us to the many Beethoven Lieder that Lehmann performed. And instead of his serious side, we’ve chosen the lighter aspect of Beethoven. Lehmann seems to relish the situation of the cheeky boy stealing a kiss in this 1941 recording of “Der Kuss” (the Kiss). 341a Der Kuss

| Ich war bei Chloen ganz allein, Und küssen wollt’ ich sie. Jedoch sie sprach, sie würde schrein, Es sei vergebne Müh! Ich wagt’ es doch und küßte sie, Trotz ihrer Gegenwehr. Und schrie sie nicht? Jawohl, sie schrie — Doch lange hinterher | I was alone with Chloe, and wanted to kiss her; but she said that she would scream, it would be a futile attempt. Yet I dared, and kissed her despite her resistance. And did she not scream? Yes, she did but not until long afterward. |

One can fill four CDs with Lehmann recordings of Schubert Lieder; in another section we offer Winterreise. Here we’ve chosen a 1947 recording of the rather formal “An den Mond” (Geuss, lieber Mond) to Hölty’s words, not Goethe’s. The title can be translated as “To the Moon.” The Lieder expert Philip Miller considered this Lehmann’s best Schubert recording. 399 An den Mond

| Geuß, lieber Mond, geuß deine Silberflimmer Durch dieses Buchengrün, Wo Phantasien und Traumgestalten immer Vor mir vorüberfliehn! Enthülle dich, daß ich die Stätte finde, Wo oft mein Mädchen saß, Und oft, im Wehn des Buchbaums und der Linde, Der goldnen Stadt vergaß! Enthülle dich, daß ich des Strauchs mich freue, Der Kühlung ihr gerauscht, Und einen Kranz auf jeden Anger streue, Wo sie den Bach belauscht! Dann, lieber Mond, dann nimm den Schleier wieder, Und traur’ um deinen Freund, Und weine durch den Wolkenflor hernieder, Wie ein Verlaßner weint! | Pour, dear moon, pour your silver glitter down through the greenery of beeches, where phantasms and dream-shapes are always floating before me! Reveal yourself, that I may find the place where my darling often sat, and often forgot, in the wind of beech and linden trees, the golden city. Reveal yourself, that I may enjoy the bushes which swept coolness to her, and that I may lay a wreath upon that pasture where she listened to the brook. Then, dear moon, then take up your veil again, and mourn your friend, and weep through the clouds as one abandoned weeps! |

Besides the song cycles Dichterliebe and Frauenliebe und -Leben, Lehmann sang many other Schumann Lieder. Her mastery of the Lied can be heard in this 1941 CBS radio broadcast of Schumann’s “Der Nussbaum” (The Nut Tree) telling of the young girl who dreams of her impending marriage. Just listen to the intimacy Lehmann brings to the last words. Der Nussbaum

| Es grünet ein Nußbaum vor dem Haus, duftig, luftig breitet er blättrig die Äste aus. Viel liebliche Blüten stehen d’ran; linde Winde kommen, sie herzlich zu umfahn. Es flüstern je zwei zu zwei gepaart, neigend, beugend zierlich zum Kusse die Häuptchen zart. Sie flüstern von einem Mägdlein, das dächte die Nächte und Tage lang, wüsste, ach! selber nicht was. Sie flüstern – wer mag verstehn so gar leise Weis’? flüstern von Bräut’gam und nächstem Jahr. Das Mägdlein horchet, es rauscht im Baum; sehnend, wähnend sinkt es lächelnd in Schlaf und Traum. | A walnut tree flourishes in front of the house, Fragrantly, airily spreading out its leafy branches. Lovely blossoms bloom on every branch; gentle winds come, to gently caress them. They whisper, paired two by two, gracefully inclining to kiss their tender heads. They whisper about a maiden who wonders all night and all day wonders… but alas! she doesn’t herself know. They whisper – who can understand this muffled tale? they whisper of a bridegroom & of next year. The maiden listens, the tree rustles; yearning, hoping, she sinks smiling into sleep and dream. |

Lehmann devoted complete recitals to the Lieder of Brahms and recorded many Brahms songs, but none with more charm and character than this 1932 “Sandmännchen” (Little Sandman) which maintains its lightness in spite of the instrumental accompaniment. 198 Sandmännchen

| Die Blümelein sie schlafen schon längst im Mondenschein, sie nicken mit den Köpfen auf ihren Stengelein. Es rüttelt sich der Blütenbaum, es säuselt wie im Traum: Schlafe, schlafe, schlaf du, meine Kindelein! Die Vögelein sie sangen so süß im Sonnenschein, sie sind zur Ruh gegangen in ihre Nestchen klein. Das Heimchen in dem Ährengrund, es tut allein sich kund: Schlafe, schlafe, schlaf du, meine Kindelein! Sandmännchen kommt geschlichen und guckt durchs Fensterlein, ob irgend noch ein Liebchen nicht mag zu Bette sein. Und wo es nur ein Kindchen fand, streut er ihm in die Augen Sand. Schlafe, schlafe, schlaf du, meine Kindelein! Sanndmannchen aus dem Zimmer, Es schläft mein Herzchen fein, Es is gar fest verschlossen Schon sein Guckäugelein. Es leuchtet morgen mir Willkomm das Äugelein so fromm! Schlafe, schlafe, schlaf du, meine Kindelein! | The flowers are long asleep In the moonlight; They nod their heads On slender stems. The blossoming tree’s a-quiver, Whispering as in a dream: Sleep, sleep, my child! The birdies sang so sweetly While the sun was shining; Now they’ve gone to sleep In their little nests. Only the cricket sings his song Deep in the meadow. Sleep, sleep, my child! The Sand Man sneaks up And peeks in the window To see if some little darling Is not in bed. Whenever he finds a child He strews sand in his eyes. Sleep, sleep, my child! Sand Man, go away now, My dear one’s fast asleep, His peepers tightly closed. Tomorrow morning Those innocent little eyes Will shine again to greet me. Sleep, sleep, my child! |

On 18 October 1938 Lehmann sang an all-Wolf recital in New York’s Town Hall. Few singers at that time offered such a program. Furthermore, she had the audacity to begin this recital with Wolf’s most demanding song, Goethe’s “Kennst du das Land.” It’s vocally strenuous and for the pianist, almost a virtuoso piece. The familiar poem translates as “Do You Know the Land,” which may have had special appeal for Lehmann, who had only months before left her home in Austria shortly before the Nazis entered Vienna and annexed the country. This whole recital was broadcast on AM radio. A fan placed a microphone in front of the radio’s speaker and recorded the recital on acetate discs. Luckily for music-loving history, these discs found their way to a secure archive at the University of Missouri, Kansas City. It is from that set of discs that Lani Spahr resurrected this immortal performance. Even with such sonic limitations, every nuance of the sung poetry is clear and heart-wrenching in its import. Though there is distortion, the piano part is also powerful. Kennst du das Land

| Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühn, Im dunkeln Laub die Gold-Orangen glühn, Ein sanfter Wind vom blauen Himmel weht, Die Myrte still und hoch der Lorbeer steht? Kennst du es wohl? Dahin! dahin Möcht ich mit dir, o mein Geliebter, ziehn. Kennst du das Haus? Auf Säulen ruht sein Dach. Es glänzt der Saal, es schimmert das Gemach, Und Marmorbilder stehn und sehn mich an: Was hat man dir, du armes Kind, getan? Kennst du es wohl? Dahin! dahin Möcht ich mit dir, o mein Beschützer, ziehn. Kennst du den Berg und seinen Wolkensteg? Das Maultier sucht im Nebel seinen Weg; In Höhlen wohnt der Drachen alte Brut; Es stürzt der Fels und über ihn die Flut! Kennst du ihn wohl? Dahin! dahin Geht unser Weg! O Vater, laß uns ziehn! | Do you know the land where the lemon trees blossom, Among dark leaves the golden oranges glow, A gentle breeze from blue skies drifts, The myrtle is still, and the laurel stands high? Do you know it well? There! there I would go with you, my beloved. Do you know the house? On columns rests its roof. The great hall glistens, the chamber shines, And the marble statues stand and look at me: What have they done to you, poor child? Do you know it well? There! there I would go with you, oh my protector. Do you know the mountain and its path amidst the clouds? The mule searches in the fog for its way; In caves dwells the dragon of the old breed; The cliff falls, and over it the flood! Do you know it well? There! there Leads our way! oh father, let us go! |

Lehmann felt a deep connection with Strauss Lieder because she knew the composer personally and had even sung his songs with Strauss at the piano when visiting him at his cozy home in Garmisch. We’ve chosen “Du meines Herzens Krönelein” (You My Heart’s Little Crown), which was Lehmann’s last studio recording. At age 61, Lehmann’s way with every subtle shading is as evident as at any time in her career. 419 Du meines Herzens Krönelein

| Du meines Herzens Krönelein, du bist von lautrem Golde, wenn andere daneben sein, dann bist du erst viel holde. Die andern tun so gern gescheit, du bist gar sanft und stille, daß jedes Herz sich dein erfreut, dein Glück ist’s, nicht dein Wille. Die andern suchen Lieb und Gunst mit tausend falschen Worten, du ohne Mund- und Augenkunst bist wert an allen Orten. Du bist als wie die Ros’ im Wald, sie weiß nichts von ihrer Blüte, doch jedem, der vorüberwallt, erfreut sie das Gemüte. | You, my heart’s crown – you are made of sheer gold. When others are beside you, then you are only more beautiful. The others like to be so clever, but you are so gentle and quiet: that you delight every heart is your good luck, not your active intent. The othes search for love and good will with a thousand false words, but you, without an artful tongue or eye, are considered worthy in every place. You are like a rose in the forest: you know nothing of your own bloom, but everyone who passes by rejoices in his mind to see you. |

The Unknown Lehmann. Most classical-music listeners of today know little about singers of the past, including Lehmann. It isn’t always easy to listen to the older recordings, and we do have many first-rate singers in our own time. However, they may not be as “intensely communicative” as Lehmann was; their portrayals may not “break through all the limitations of conventional operatic acting;” they may lack “the capacity to endow the vocal line with a breadth befitting Wagner’s immense canvas yet to retain always the purely musical finish she might have bequeathed to a phrase of Hugo Wolf…” These quotes are from Lehmann critics of her time. Even for the most ardent Lehmaniac, there is another unfamiliar, or at least under appreciated aspect of Lehmann’s career, and that is the huge number of recordings of works not part of her famous canon. In Vienna, she actually appeared as Massenet’s Manon more frequently than as the Marschallin or Fidelio. This 1924 recording of “Folget dem Ruf” (Obéissons quand leur voix appelle) (Follow the Voice that Calls) demonstrates her flirtatious side, as Manon. 049 Folget dem Ruf

She sang in many operas that were composed in her time, but unheard in later years. In 1927 she created the title role of Heliane in Korngold’s Das Wunder der Heliane (The Miracle of Heliane). Here’s an excerpt from the opera’s most famous aria in which you’ll hear both the glorious sound of Lehmann’s voice, and the intensity of the drama. What a difference the newly invented microphone makes! 107 Ich ging zu ihm

Lehmann sang the lead in Mignon by Ambroise Thomas, in both Hamburg and Vienna. The opera was originally written in French to the Goethe story. In German-speaking lands it was translated into German and it’s thus that we hear Goethe’s famous original poem “Kennst du das Land” in this 1930 recording. This is one of the earliest poems that the young Lehmann learned and she always delighted in the chance to recite it. 069 Kennst du das Land

Lehmann also performed then-living composers’ Lieder that are seldom heard now. In 1932, for instance, she performed for the 50th birthday party for Josef Marx, given on stage in Vienna with the composer at the piano. In 1937 Lehmann recorded an ecstatic version of his “Selige Nacht” (Blessed Night) with Ernö Balogh, pianist. Though Marx isn’t well-known today, RCA Victor thought highly enough of him in 1937 to offer Lehmann the chance to perform this song. 267 Selige Nacht

Another segment of Lehmann’s career that remains unknown is the familiar operas not usually associated with her. The demanding tessitura of Turandot seems beyond her lyric soprano range, but she sang the Vienna premier, and performed the role in Hamburg, Breslau, and Berlin as well. In this rare 1927 recording (082) you’ll hear Lehmann handle the high “C’s” with aplomb. You may also hear notes missing from the Ricordi score which have now been rediscovered and are again being performed. 082 Die ersten Tränen

Lehmann sang only one Verdi role, that of Desdemona in Otello. She performed it in Vienna, Budapest, Berlin, and London. In London, the demanding critic of the Gramophone wrote, “…Lotte Lehmann did so magnificently both as singer and actress that she rose to heights never attained here before…” Herman Klein and The Gramophone, edited by William R. Moran. In this 1932 recording (193), Lehmann sings the famous “Willow” aria that ends with Desdemona’s premonition of death. 193 Sie sass

She enjoyed great fame for her many-faceted portrayal of Eva in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger. Few singers in recorded history have ever portrayed a more impetuous Eva, as she greets Sachs, acknowledging their past love and her anticipated future. Even this 1920 recording (040) (microphones hadn’t been invented yet) captures much of Lehmann’s spontaneity. This fun aria is “O Sachs mein Freund” (Oh Sachs My Friend.) 040 O Sachs! Mein Freund!

Perhaps to compete with her Vienna Opera rival Maria Jeritza, Lehmann sang the role of Tosca. It wasn’t her style of character and she didn’t receive the same acclaim that critics and audiences gave to Jeritza, but she sang Tosca in Berlin as well as at the Met, and in San Francisco. Here’s a 1929 recording of Lehmann singing “Vissi d’arte” in German. 149 Vissi D’arte

Hermann Götz wrote Der Widerspenstigen Zähmung (inspired by Taming of the Shrew). Lehmann sang the opera a few times in Vienna and recorded the tuneful aria of Katharina in 1919 (028). She sang it in many concerts throughout the years, with great success. 028 Es schweige die Klage Though she didn’t encourage her students to sing “mixed” concert recitals, she often did so herself. Perhaps it was in accord with the wishes of her sponsors.

There are many such “contemporary” operas that Lehmann sang in Hamburg and Vienna that just haven’t endured. Eugen d’Albert’s Die toten Augen was such a success for Lehmann that she sang it during her last weeks as a member of the Hamburg Opera company. Blind Myrtocle is given sight by the touch of Jesus. According to the libretto, the first thing she’s supposed to ask for is a mirror. Lehmann thought that detracted from Myrtocle’s character and wouldn’t sing those words. The composer was so taken by Lehmann’s suggestion that he actually allowed her to change his opera. Here is the 1933 recording that she made of the opera’s most enduring aria (206). 206 Psyche wandelt Psyche wanders through columned halls. Sweet sounds and songs reverberate, Rose fragrance from golden chalices, Rich treasures glow and shine, Poor little Psyche! Night times she feels her husband’s kisses So pure that she must almost faint, She hears his voice in sweet delight, But never can she view her beloved. Poor little Psyche! And furtively with a small lamp, She steals to him with soft steps, And sees splendor for blessed hours, Amor, the God, and then He vanishes. Poor little Psyche.

An aspect of Lehmann’s career that some strictly “classical” music lovers find compromising is her participation in operetta and the popular music of the time. She sang various operettas in Hamburg, Vienna, and Die Fledermaus even in London. She recorded music from that as well as other operettas. She seems to have had a lot of fun while singing the following excerpt from Otto Nikolai’s Merry Wives of Windsor. In the 1932 recording that follows you’ll hear her conniving with her friends on how to trick Sir John: “Er wird mir glauben” (He’ll Believe Me)(190) 190 Nun eilt herbei

Frau Fluth gathers her pals together to play a prank on the flirtatious Sir John, the fat glutton. She will pretend to love him and he’ll fall for it, but it’s all in fun. “A happy sense of humor spices up life, and to forgive is as good as the joke. After all, real love and faithfulness stay in the heart.”

| Now hurry here, jokes, bright humor, the greatest pranks, cunning and bravado. Nothing is too wicked, if it serves to punish men without pity. That is a group, so awful, that one cannot complain enough about them. Before all others that fat glutton, who wants to seduce us. Ha ha ha ha! He should pay the penalty. But when he comes, how will I have to behave? What will I say? Stop! I already know! Seducer! Why do you set a trap for a virtuous spouse? Why? Seducer! The outrage will never subside. No, never, my anger must be your punishment. | However, a woman’s heart is weak. You complain so pathetically about your pain. You sigh, my heart becomes weak. No longer can I be cruel, and I confess it, shamefully blushing, to you, my knight. I love you. I love you. Ha ha ha ha. He will believe me, performing I can do very well. A bold risk is it indeed, only for fun may one allow it herself. Happy sense and humor spices up life and to forgive is well a joke. So for pleasure may one lie. Real love and faithfulness stay in the heart. Therefore full of trust, dare I to do the deed. Happy women, yes, who know their own advice. |

In 1929 Lehmann even sang a real pop hit, Hans May’s “Der Duft, der eine schöne Frau begeltet” (The Aroma that Accompanies a Beautiful Woman). Listen for the real Viennese rubati that she brings to this song. (Just try conducting a square 4/4.) 146 Der Duft, der eine schöne Frau umgibt

In her mid-eighties Lehmann would listen to only one of her recordings and that was this light, Bavarian-dialect folk song “Zuschau’n” (Peeking) which she had recorded when she was 43. 183 ‘s Zuschau’n

Some listeners find Lehmann’s rather large output of devotional music (recorded in her early years) a bit embarrassing, but one hears conviction in these recordings that belies her own rather ambiguous religious beliefs. In this 1928 recording Lehmann’s voice balances well with the organ and sounds almost like an intimate prayer: “Wo du hingehst” (Where You Go Forth) (134). 134 Wo du hingehst

The most troublesome (even annoying) recordings to hear today are the Lieder that Lehmann recorded for Odeon with salon-orchestra accompaniment. The record companies didn’t think that the buying public was getting its value if there was only a piano. Not only does this violate the composers’ intentions, but the quickly written and poorly played arrangements can sound soupy and corny to our ears. Compare the orchestra version of the 1929 Strauss “Ständchen” (Serenade) (156) with the 1941 version with the original piano accompaniment (353). 156 Ständchen 353 Ständchen

Even Lehmann fans may not know that she toured with Lauritz Melchior, performing shared recitals. They were even booked into Carnegie Hall. RCA made a recording (sadly with orchestra) of some of the Schumann duets that were featured on the tours. But there’s still much to enjoy in the following 1939 recording of “Er und Sie” (He and She). 289 Er Und Sie

Lehmann students (now mostly retired) have many Lehmann stories to tell and some, like Marilyn Horne and Grace Bumbry, have even given recitals honoring Lehmann.

Many people who closely follow Lehmann’s singing don’t know that she recorded two LPs of poetry readings and spoken excerpts from Der Rosenkavalier. You can hear a sample of each: Goethe’s “Der du von dem Himmel bist” (You Who Are From Heaven) and a portion of the Marschallin’s Act 1 monolog. Der du von dem Himmel bist LL reads from Der Rosenkavalier

So much for the “unknown” side of Lehmann! Her fame, if that is the right word, is maintained by the many studio recordings that are frequently re-released. Lehmann biographies continue to be written and many of the books she wrote remain in print, all of which preserves a degree of “legendary” status. Lehmann spoke often of enjoying three lives—as an opera singer, a recitalist, and a teacher. She accomplished all three careers with distinction. Three Careers on 85th bday tribute

Though today her name is generally unnoticed and unrecognized, for the vitality, commitment, and sheer beauty she brought to her art, Lotte Lehmann deserves all the full legendary status that her talent and hard work engendered.

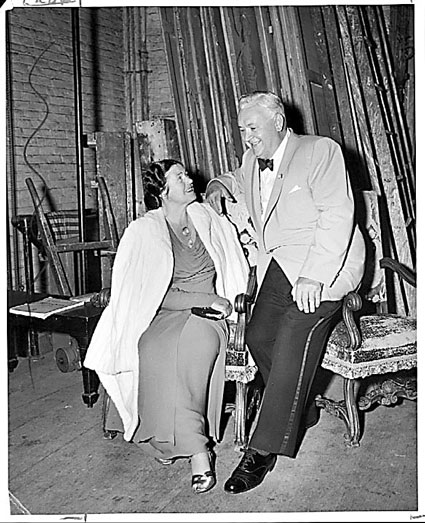

Look carefully at this photo, taken in a rehearsal for a Salzburg Festival performance of Fidelio, you can almost feel the excitement generated by two legendary musicians of their time: Toscanini and Lehmann. Just upstage from Maestro stands the famous stage director, Lothar Wallerstein. Next to Maestro is Erich Leinsdorf.