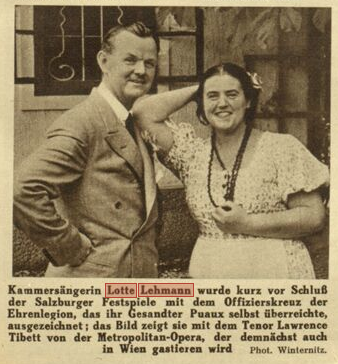

LL Photos from Newspapers

The following photos have a distinct look, having been printed in newspapers, many years ago. So there’s a nostalgic feeling.

LL Film Planned

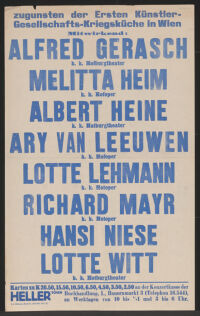

This recently discovered newspaper article from 1935 offers the “What IF?” question to the past.

Gerron to direct Lotte Lehmann film

Lotte Lehmann is now also set to star in a film. She will portray a great singer who must grapple with the conflict between her career and her private life. She tries to renounce her art to save her marriage and family happiness. However, she doesn’t quite succeed, and ultimately returns to her art. Kurt Gerron will direct the film. Negotiations with Ms. Lehmann are expected to be finalized in the coming days, with only financial details remaining to be settled. Filming is scheduled to begin in September. 1935

New Photos Arrived (Thanks to Herr Clausen)

LL’s Students Obituaries

We have finally completed the page that offers obituaries of all of Lehmann’s Music Academy of the West students (the students we know of). Often you’ll find the student’s recorded memories of working with Lehmann. For some of the lesser known students we have included some recordings of their work.

Town Hall, Australia

With Melchior

Lois Alba Passes

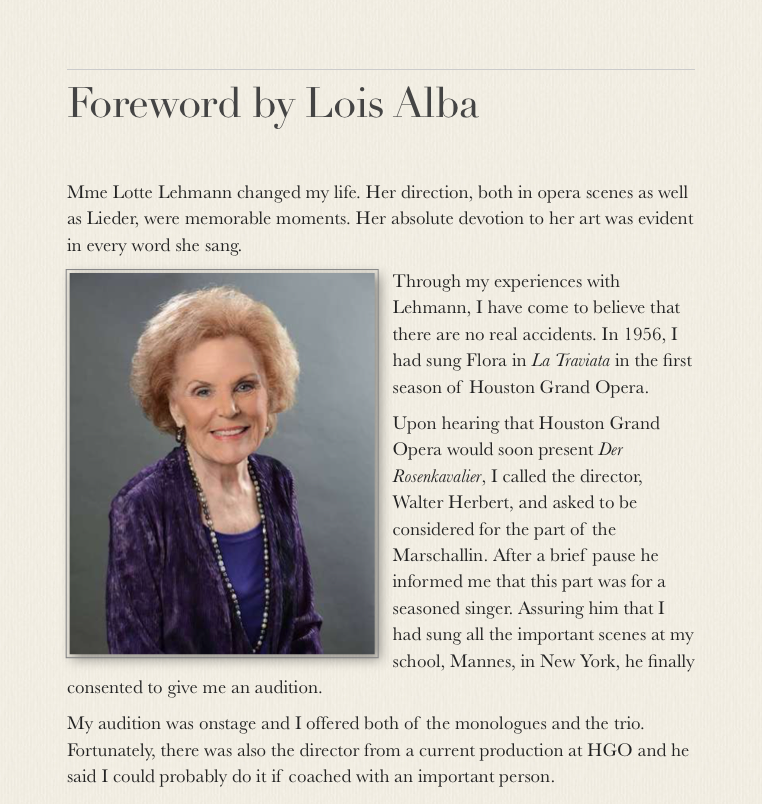

Lois Alba Plummer Townsend Wachter (1928-2025) fell in love with opera at an early age and began taking singing lessons when it became apparent that she had a natural talent and drive.

She graduated from Kinkaid School in Houston at the age of 16 and moved to New York City (with a chaperone) to study music, acting and voice at Mannes as well as the Daykarhanova School for the Stage founded by bormer members of Stanislavsky School of Acting in Russia.

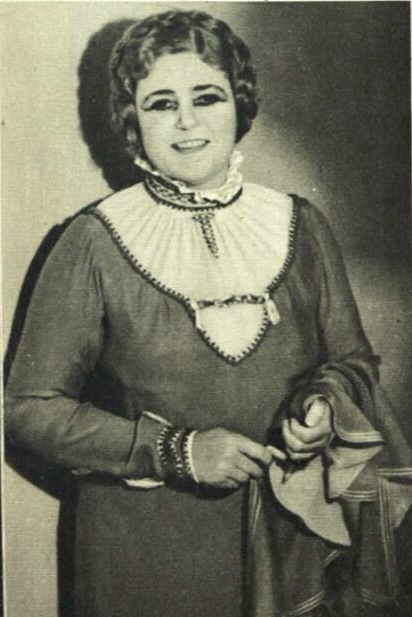

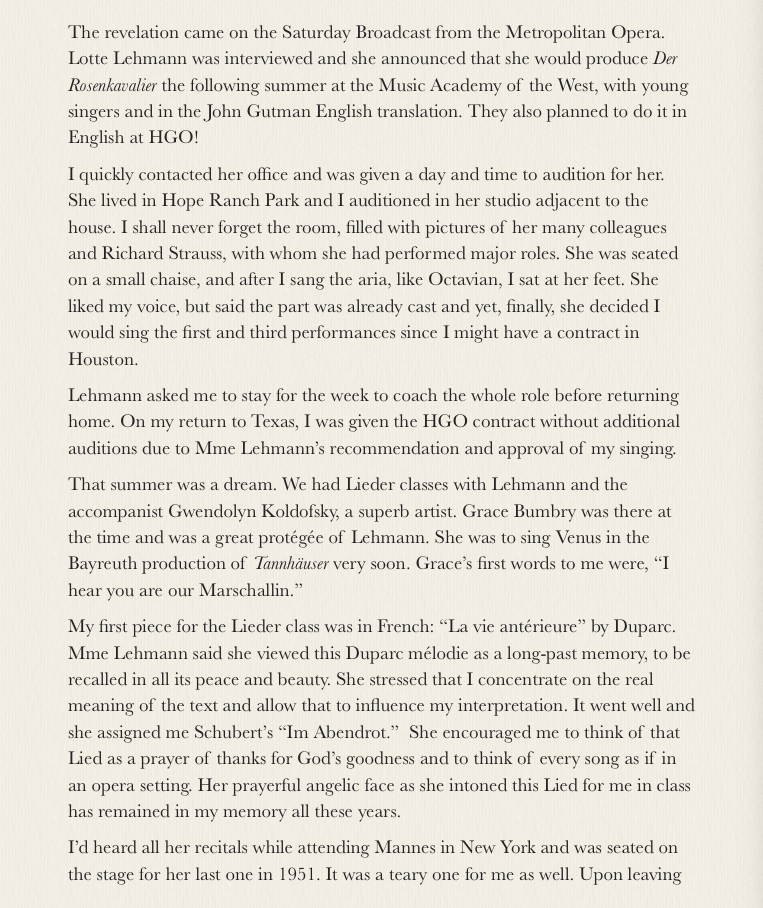

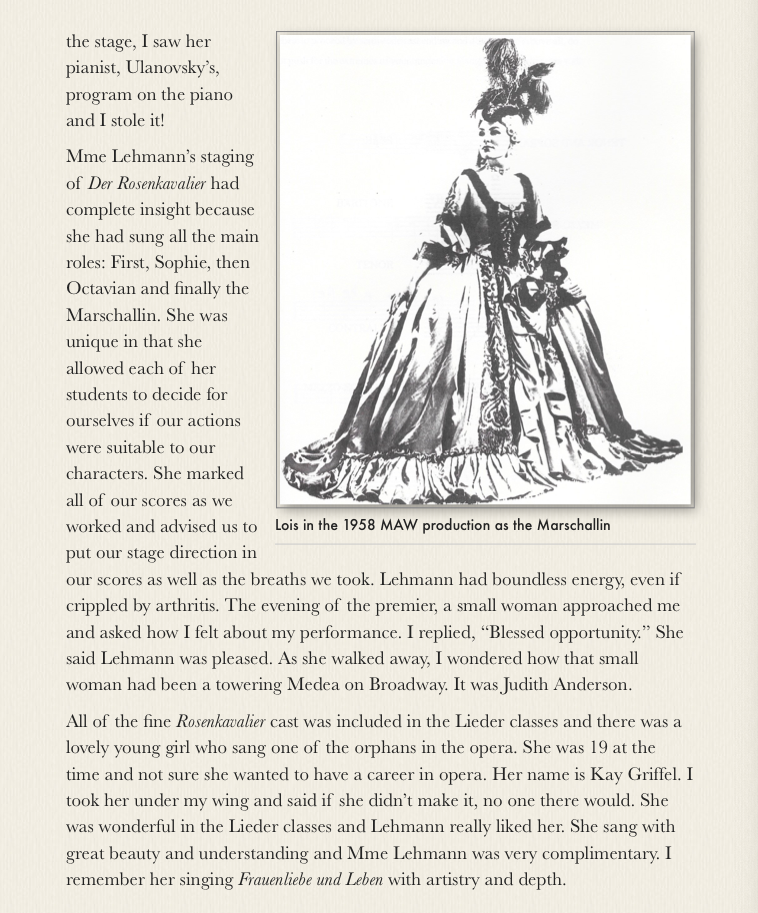

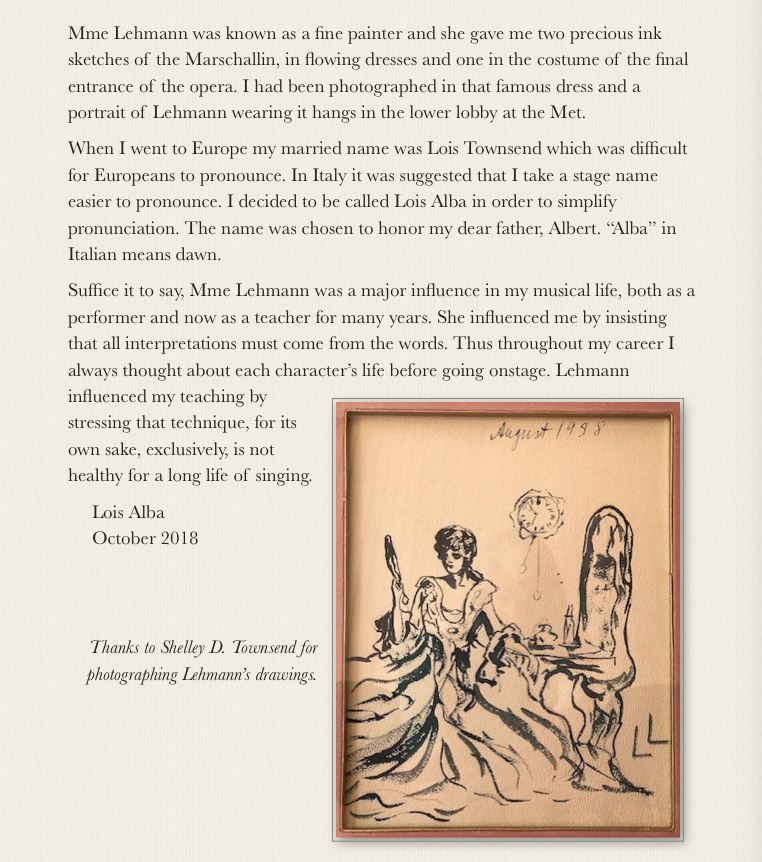

She became the first winner of the Southwest Division of the Metropolitan Opera Competition. Later she prepared the role of the Marschallin in Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier with Lotte Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West where she sang in their production. There she studied other roles and Lieder with Lehmann.

She subsequently sang the role at Houston Grand Opera. She proceeded to perform in recitals and concerts. She met Texas real estate developer, Herbert Townsend. They married and had three children. Her colleagues, including Lehmann, recommended that Lois move to Europe to further her career, which she did and lived in Paris and Milan for 11 years.

A student of bel canto, Lois furhtered her studies with a number of famous singers such as Rosa Ponselle. She appeared in opera in Europe for eleven years performing in the company of many acclaimed singers including Mirella Freni, Mady Mesplé, and Luciano Pavarotti. She performed leading roles in La Traviata, Cosi fan tutti, Turandot, La boheme, Le nozze di Figaro, Otello, Die Zauberflöte and Mefistofle.

Her marriage to Herbert ended amicably. She returning to NYC to live, where she met Arthur Wachter whom she married. Together they founded Soma International Foundation to help young singers advance their careers. They ultimately returned to Houston to be closer to family, and with the help of fellow artist Bettye Gardner and tenor Johnny Jennings, they founded Opera in the Heights and produced many operas there.

In 2016, Lois developed The Lois Alba Aria Competition that enjoyed a 14 year run. They sponsored fundraising events and concerts to earn prize money to help singers further their careers. She maintained a full studio of singers as well.

Her legacy of teaching spaned over 50 years. Lois published Vocal Rescue: Rediscover the Beauty, Power and Freedom in Your Singing.

Following is the Foreward she wrote for Gary Hickling’s iBook Volume 6 in the series Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy.

1986 MAW Tribute

Richard Strauss

LL as Composer

Unusual Photo

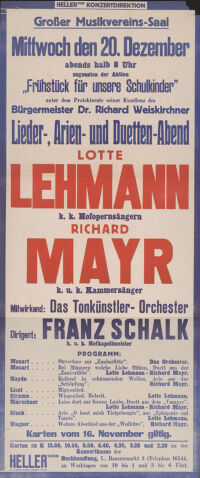

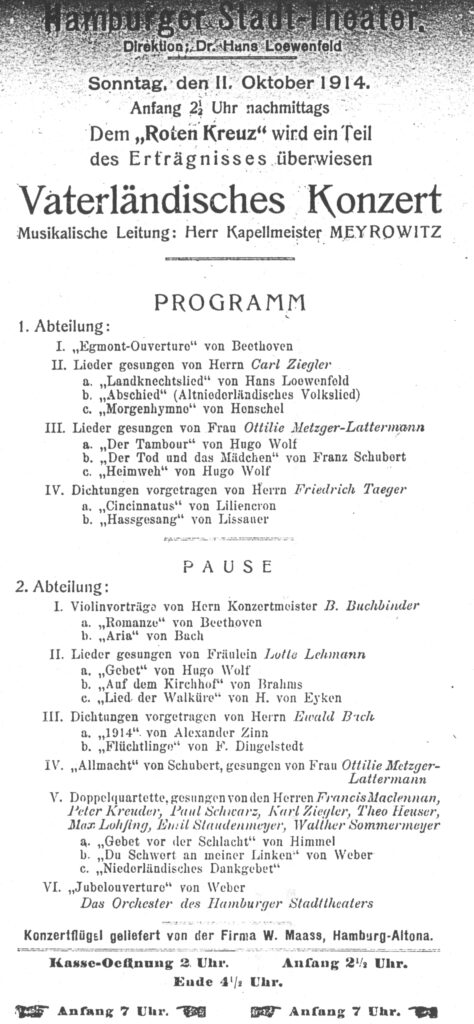

First LL Playbill

You need to scroll down to see it because Lehmann wasn’t the only soloist on this concert. But there she is performing songs of Wolf, Brahms, and von Eyken. This must have made the young singer and her parents very proud! You can see other such early playbills on this site.

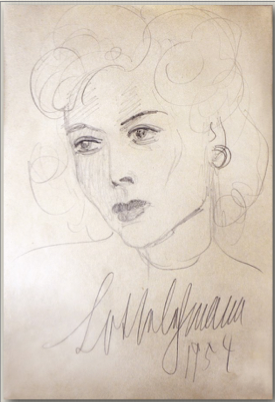

Benita Valente Has Passed

Born 19 October 1934, Benita Valente died on 24 October 2025. Because she’d studied interpretation with Lehmann for six years, Valente was an obvious person to write the Preface to the iBook Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy Volume 2. Here, along with the painting that Lehmann herself drew of her student, a few photos, and an actual master class that Lehmann taught to Valente, that Preface. That is followed by the New York Times obituary.

“On the long path to becoming a professional singer, I was fortunate to work with a number of exceptional musicians. My high school music teacher in Delano, California, Chester Hayden, was the first among them, and it was he who led me to the legendary German opera and Lieder singer Lotte Lehmann.

“Lehmann, who had just retired from the stage and was heading the vocal program at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, accepted me for the nine-week summer session in 1953. Based on what she heard in our voices, she created an individual recital program for each singer whom she took on as a student. This was a special and unique gift, reflecting her largesse, and it proved to be of great value to me as I continued in my studies.

“In all, I spent four summers at the Academy. After the second summer, I moved to Santa Barbara and, shortly after that, was accepted at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where I studied with baritone Martial Singher, but continued at the Academy for two more summers.

“The schedule there was intense. From Monday through Thursday, we would prepare the repertoire that Lehmann had chosen for us for her master classes, working with soprano Tilly de Garmo on vocal technique and with her husband, conductor/coach Fritz Zweig, at the piano. They were among many gifted musicians who had fled Nazi Germany for the United States, and we were so fortunate to have the opportunity to learn from them.

“On Friday and Saturday, Lehmann held two-hour master classes on interpretation, open to a paying audience and held in a large, elegant room of the Spanish-style mansion located on a cliff near the Pacific Ocean. Fridays were devoted to German and French art songs and Saturdays to operatic arias and scenes. The roughly eighteen students sat in the hall observing, and Lehmann (whom we always called “Madame Lehmann”) would call us to the stage individually, or as a group for opera scenes, to perform selections from the repertoire selected for study that week. Occasionally, when she heard a vocal problem, she would refer us to Tilly, and, during one summer, to tenor Armand Tokatyan.

“The first Lied I sang for Lehmann in 1953 was Schumann’s “Die Lotosblume,” set to a poem by Heine. Because I had not heard German spoken or sung before, it took me two weeks to memorize the song, but there was a lotus pond down the road from the Academy that I used for inspiration. I also sang “Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht” by Brahms, which struck me deeply because my mother had died in 1954. Lehmann must have felt my strong connection with the music, for she was gentle with her critique.

“In a professional career of over four decades, Lehmann had shown an amazing gift for taking on virtually any role or song and making it her own. She was always guided by the text, which she considered to be the key to expression and color. As her students, we reaped the benefits of this vast experience. We had to memorize each piece, and if we forgot the text Lehmann, puzzled, would say: “I would rather have forgotten the music than the words.”

“Sometimes, when we just couldn’t achieve the results she wanted, Lehmann would step onto the stage to sing an aria or song, often an octave lower, that we were working on. On days when her allergies were not bothering her, she would sing it as written. Watching and listening to her, we were mesmerized by her ability to transform herself magically into another persona and overwhelmed by the depth and range of emotion she expressed.

“She opened us up to the many possibilities of interpretation and made it clear that she did not want us to copy her, but to develop our own means of expression. By the end of each class, I had experienced such a range of emotions that I found I had developed a splitting headache and had to go back to my room to lie down.

“Lehmann had sparkling blue eyes and wore elegant but simple ankle-length dresses, sometimes with a scarf of the same beautiful material. When each session was over she would sweep out of the room past the audience, surely aware of the impression she had made on us, her spellbound students. Yet she was, at the same time, a warm and friendly presence and took a personal interest in her students, being especially curious about our love life. “Haf you never been in love?” she would ask if we lacked the requisite romantic emotion in a song, and she would rhapsodize about moonlight, innocently translating the German word “Mondschein” into “moonshine.”

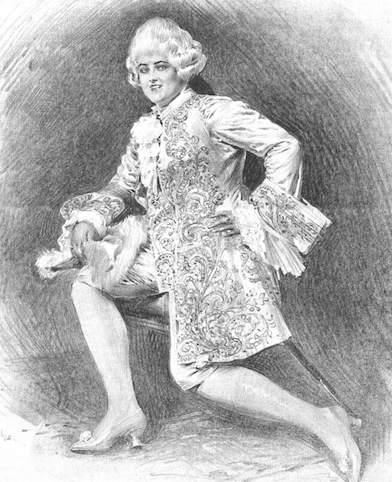

“Learning how to act and move on stage was another aspect of our training. We were all somewhat awkward and needed to learn the basics. I remember being taught how to die in operatic fashion by our handsome acting coach, tenor Carl Zytowski, and one day Lehmann said to me in class, “Benita, I have heard that you have learned to die beautifully. Please die for us”—which I did! The acting lessons were valuable for our opera scenes and for the complete operas that were staged once a summer, though my skill in dying was not called for in the roles I was given: Barbarina in Le Nozze di Figaro, the Echo in Ariadne auf Naxos, and Adele in Die Fledermaus.

“Another major influence at the Academy was Lehmann’s older brother, Fritz Lehmann, a highly regarded vocal coach who came to all the master classes and worked individually with some of us in his home in Santa Barbara, in the presence of his warm and loving wife, Theresa. Fritz shared my great love of Mozart and recognized that Mozart’s arias and songs were ideally suited to my voice. How right he was! Mozart became the cornerstone of my operatic career, with such roles as Pamina in Die Zauberflöte; Susanna, and later the Countess, in Le Nozze di Figaro, and Ilia in Idomeneo.

“In addition to the summers at in Santa Barbara, I spent a winter there as part of a small group of singers working with Lehmann solely on Lieder. In this more intimate setting with students she knew well—at the end of each master class— Lehmann would sweep out of the room in her usual graceful fashion, pass us by and say: “Goodbye children.” Eventually I summoned up the courage to respond: “Goodbye, Mother.” One day there was an outsider in the room and I didn’t want to embarrass anyone, so I said nothing. Lehmann walked by me, looked at me, and, with a twinkle in her eye, silently mouthed the words “Goodbye, Mother.”

“Lehmann’s immense curiosity drew her into many areas of life. She enjoyed creating art and did a painting for each song of Schubert’s song cycle, Winterreise. One of those paintings hangs in my studio. She loved gardening and made the tiles for the steps of her garden. She was a frequent letter writer, her handwriting large and sprawling and her words revealing her characteristic truthfulness and emotional openness.

“Lehmann had a great love of animals. She owned two myna birds who could be heard from the garden imitating her speaking voice exactly. Once Lehmann asked soprano Shirley Sproule, who was my colleague and voice teacher at that time, to drive her to Los Angeles, and I happily went along, thrilled to be in her company. On our return we passed a schoolyard. Lehmann spotted a crow perched on the monkey bars. Although we assured her that the bird was fine, she later apparently worried that it was caught in the bars and insisted that her friend Frances Holden drive her back to the schoolyard. No bird remained—it was free!

“In my current life as a teacher of voice, I think often of Lotte Lehmann, of her larger-than-life personality, her magnetism, her ability to become different people on stage. No wonder such major creators as Richard Strauss, who composed music for her, and Arturo Toscanini, who conducted her in performance, were so entranced by her! For me personally, one of Lehmann’s most important gifts was to open my path to loving the Lied and the song repertoire in general. Her equal commitment to opera and art songs has inspired me to follow the same path, adding chamber music, oratorio, and contemporary works to my own repertoire. I have accepted as key her principle that the words lead the way to the expression and color that the composer intended.

“Lotte Lehmann, along with pianist Rudolf Serkin, who was a mentor to me at the Marlboro Music School and Festival in Vermont, and soprano Margaret Harshaw, with whom I studied from 1969 until 1995, two years before her death, were the musical greats who inspired me in my life in music. Passing on their artistic vision to future generations is both my responsibility and my privilege.”

Der Hirt auf den Felsen

[I received the following email message from Ms. Valente in March 2016] …thanks for urging me to write this Foreword, for it caused me to bring back to mind so many wonderful memories that I have stored away all these years!

[Here is a Lehmann master class at the MAW from the early 1950s in which Valente sang Schumann’s “Soldatenbraut.”]

Benita Valente, Acclaimed Bel Canto Soprano, Is Dead at 91

Her career spanned decades, included performances at the Metropolitan Opera and brought her effusive praise from critics and operaphiles.

By Jonathan Kandell

Oct. 25, 2025, 3:31 p.m. ET

Benita Valente, an American light soprano who was acclaimed for the faultless technique and intelligence of her performances in operas, recitals and chamber music, but who inexplicably failed to gain a wider following among classical music audiences, died on Friday at her home in Philadelphia. She was 91.

Her son, Pete Checchia, confirmed the death.

Whenever an aria or a song required it, Ms. Valente demonstrated exquisite control of chromatic vocal lines and an effortless mastery of her high notes, matched lower down her range by admirable freedom and control.

In opera, her voice was ideally suited for a role like Pamina in Mozart’s “The Magic Flute,” which she performed more than 200 times. Critics raved about her interpretations of cantatas by Bach. In lieder, few of her peers could match her renditions of Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann and Hugo Wolf.

“All the hallmarks of bel canto technique are hers to command — the ability to sing evenly at any part of her range, loud or soft; the skill to ascend smoothly through the various registers; a complete lack of obtrusive wobble or hoarseness,” the Chicago-based opera and classical music commentator Brian Duffie wrote in prefacing an interview with Ms. Valente in 1987. “Add to that a clear, idiomatic declamation in a variety of languages, a natural musicality of phrasing and an inherently dignified, sympathetic public personality, and you have an artist to reckon with.”

Yet despite such effusive praise from critics, Ms. Valente’s performances did not always fill auditoriums. And she made painfully few recordings.

While she often expressed satisfaction and delight at her long, varied career, she occasionally allowed a hint of bitterness to surface when asked why she recorded so seldom.

“It’s because I haven’t been asked to record,” she told The New York Times in 1983, at the height of her career. “I’ve never been in the ‘in’ crowd.”

Benita Valente was born on Oct. 19, 1934, in Delano, Calif., in the San Joaquin Valley, where her parents owned a dairy farm and grew cotton. The youngest of four daughters, she sang duets with one of her sisters, who played the piano. She listened often to the Enrico Caruso records in her father’s collection. Her mother, who was from Switzerland, sang Swiss songs.

“I could hear this beautiful high voice floating through the air from the milk house or the barn,” Ms. Valente recalled to The Times in 1983.

Chester Hayden, her music teacher at Delano High School, persuaded her that she had the voice to sing professionally. He put her on a rigorous study program for languages, piano and the basics of singing. And he drove her to Los Angeles to audition for the German soprano Lotte Lehmann, who was teaching at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara. Ms. Lehmann accepted the young woman for studies there.

Ms. Valente later received a scholarship from the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where she studied under Martial Singher, a well-known French baritone.

In 1960 she was invited to sing at the Marlboro Music Festival in Vermont, where she met her future husband, Anthony Checchia, a bassoonist who went on to become founding artistic director of the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, the nation’s largest presenter of chamber music concerts.

Besides their son, a photographer and artist, Ms. Valente is survived by a daughter, Eliza Batlle, a psychologist. Her husband died in 2024.

After winning the Metropolitan Opera auditions in 1960, Ms. Valente made her debut with the Freiburg im Breisgau Opera as Pamina in “The Magic Flute” in 1962. She then performed frequently at the Nuremberg Opera.

She spent a dozen years in Europe waiting for invitations to perform in the United States. “I believed I would have to make it in the States or not at all,” she told The Times.

In 1973, Ms. Valente, then 38 years old, finally made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera, as Pamina.

“From the moment she came onstage,” Allen Hughes of The Times wrote in a review of that performance, “Miss Valente, the Pamina, sounded as though it was the most natural thing in the world for her to be there. Her beautifully poised voice projected admirably, and the sensitivity and authority of her style commanded instant and sustained attention.”

Ms. Valente went on to perform a full schedule of operas, recitals and oratorios for decades. But music critics and many operaphiles were mystified that her popular following remained limited.

In a glowing 1983 review of a recital of songs by Haydn, Brahms and Wolf, the Times music critic John Rockwell lamented that Ms. Valente failed to sell out Alice Tully Hall. “The curiosity,” he wrote, “lies in the discrepancy between her prodigious gifts and her relative lack of renown.”

Similarly, in his review of a sterling recital of Schubert, Haydn and Wolf songs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1985, The Times’s Bernard Holland wondered why “she remains far less known than many colleagues of smaller ability.”

Taking a stab at the mystery, Mr. Holland suggested that the answer might “lie in the peculiar nature of Valente’s musical personality — whose purity does not reach out aggressively but instead invites the attentive and the caring among her listeners to draw closer.” Such purity, he added, also “makes up for any lack of sensuous tone.”

Ms. Valente devoted herself equally to opera and song. Besides her many appearances in “The Magic Flute,” she was applauded for her performances as Gilda in Verdi’s “Rigoletto,” Violetta in Verdi’s “La Traviata” and Mimi in Puccini’s “La Bohème.”

She also made a notable mark as a chamber music performer, with a repertoire that spanned from Baroque cantatas to modern compositions. Among contemporary composers, she enjoyed close relationships with William Bolcom, who wrote several works for her, and with John Harbison, who set poems by William Carlos Williams to music texts that Ms. Valente performed in recital.

In a review of a Valente recital at the Juilliard Theater in 1999, The Times’s chief music critic, Anthony Tommasini, extolled her undiminished ability to sing Mr. Harbison’s highly charged “The Rewaking.”

“The music captures the stormy weather of the poetic imagery in tormented vocal lines,” he wrote, “but it renders the calm after the storm in melodic arcs of high, soft, sustained beauty, and Ms. Valente handled it all impressively.”

Summing up her career to The Times when she was approaching 50, Ms. Valente said, “It’s been a long, slow, wonderful crescendo.”

AI Comparisons

Two More Improved Photos

These adult photos (one not in a studio) have been greatly improved.

AI Photo

The old photo (1890) of little Lotte was difficult to enjoy, so I had it processed. Here’s the comparison of the two year old Lehmann as improved.

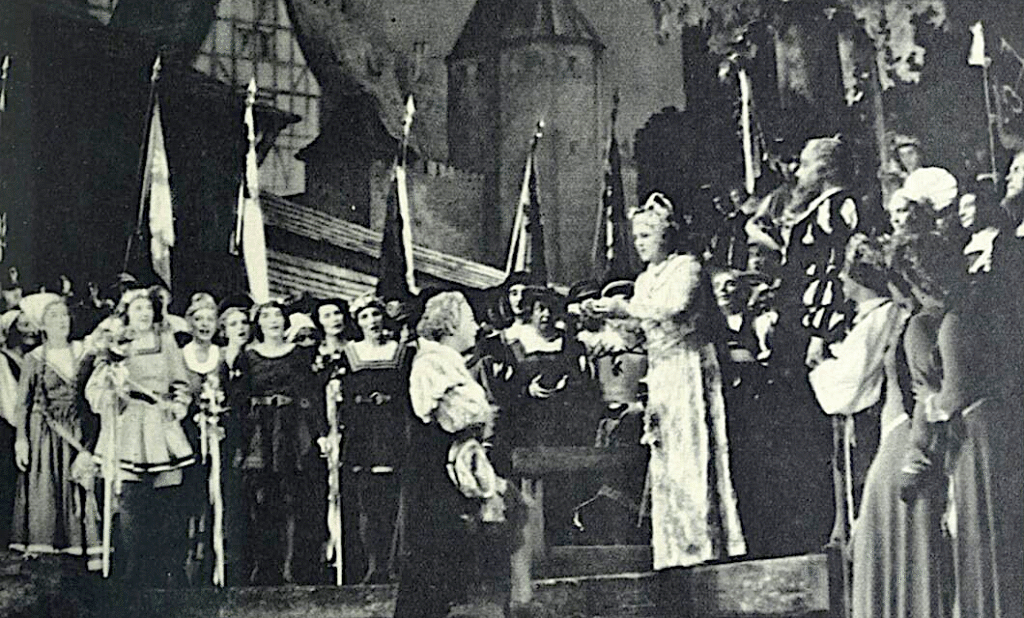

LL in Andrea Chénier

This opera came late (1926) to the Vienna Opera and Lehmann was chosen for the soprano lead role.

LL with Famous Colleagues

LL Gives O’Brien Her Painting

Here’s a photo of two of the cast of the MGM movie Big City. Lehmann gives Margaret O’Brien her own painting of them together in the film.

Another Lehmann Painting

Nitza Newman studied with Lehmann and her daughter bought this Lehmann painting for her.

A New Lehmann Painting Arrives

Candace Morgan, the great-granddaughter of Mia Hecht, one of Lotte Lehmann’s dearest friends, has sent a photo of one of Lehmann’s paintings that she inherited. Many thanks!

1935 Review

Edward Downes on LL

Edward Downes (1911 – 2001) was an American musicologist, professor, radio personality, and music critic. He was the host of the Texaco Opera Quiz on the Metropilitan Opera radio broadcasts for nearly for years.

Downes remembers:

Lehmann was the only singer I ever met who seemed to be exactly the same offstage as she was onstage. She always sounded spontaneous onstage, whether it was Abseulicher! [from Fidelio] or some casual remark. She was always totally echt… there. As if somehow it just happens in this way at this moment. That was very powerful. It was powerful enough so that it extended to her physical actions aside from singing. Particularly in Tannhäuser. One quite short moment was at the very end of Elisabeth’s role, after Allmachtige Jungfrau, when Wolfram comes on and says “May I escort you back to the castle” or whatever. She doesn’t answer with words but is supposed to gesture that the place she is going to is “up there” not “over there.” It’s a somewhat pretentious stage direction. But there are only a few bars left from that to her exit, and a relatively short distance back stage, where you saw her in profile, she made an exit in a diagonal, not singing, no gestures, just walking, and it was one of the most vivid moments I remember in opera.

She was like this in every performance. This moment was always magical. Very close to the end of her career, when I was briefly a music critic for The Boston Transcript, Lehmann came to Boston and gave a recital. It must have been one of the Morning Musicales. I hadn’t seen her in quite a long time. Since it was a morning concert, I didn’t need to rush away to write my review and I knew her somewhat. Not well, but I knew her well enough that I had been to her house for lunch. She was a warm and gracious woman, I decided to go and see her after the performance. I knew it was long enough so she probably wouldn’t remember me, but I had dined with her and her family a few times at the Salzburg Festival, and in New York I knew her well enough so that she asked me one time why I thought the Met didn’t give her more performances. My only answer was that they had this idea that for Italian opera it should be Italian singers, French for French and so forth. I didn’t really know the answer. In any case, I knew her well enough that she had asked my opinion. However, many years had gone by. Now in Boston after the recital, she was sitting at a table chatting with people and shaking hands and autographing things and she saw me come in. Somehow, I knew she recognized me, but not sure from where. But she gestured and half got out of her seat and said to me ‘Sie hat nicht ewig lange gesehen!’ Which was very tactful but it was even with the little social fib implied, still a spontaneous and honest reaction. I think this was very characteristic of everything she did.

Lehman herself mentioned in a talk she gave that when speaking to Richard Strauss he complimented her and she was doing the ‘oh, you’re so kind’ and she said ‘Aber meister, ich schwimme’ meaning I’m cheating [swimming] through your music and Strauss said ‘Ja, aber sie schwimme so schön!’ Apparently, she knew him quite well – she was after all the first Composer in the revised Ariadne and the first Farberin in Die Frau ohne Schatten, and she said “I sang that opera for ten years and I never figured out what was going on!”

Lehmann was a regular visitor to Boston during Edward Downes’ tenure on The Boston Transcript. In 1939, he reviewed her Jordan Hall recital:

30 October 1939—

It is only artists of the stature of Lehmann who are able to supply that something new we demand simply by giving a great performance of a familiar composition. And she does it, not by making poor defenseless Schubert stand on his head, nor by doing something startling and sensational with Brahms. She does it by penetrating to the very core of the composer’s thought. What stands revealed to us then is not a clever idea that Lehmann had, but Schubert or Brahms himself recalled in all the freshness of primal inspiration.

Lotte Lehmann returned to Boston to sing her famous Marschallin in Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier at the Boston Opera House. Edward Downes reviewed the performance in The Transcript:

In the ten years since this writer first heard the unforgettable Rosenkavalier of the Vienna State Opera; Lotte Lehmann’s Marschallin has changed. If it no longer has quite the same opulence of voice, her impersonation has grown in depth and subtlety. It has become even more intense and moving than it was. There are Marchallins who are more naturally aristocratic, but none more poignantly human. Last night Mme. Lehmann lived her part as did no one else on stage. The gentle dignity with which she covers her agony at the thought of growing old, of losing Octavian, her vision of herself as the old Princess, die alte Fuerstin Resi, the heartbreaking simplicity of the pantomime that closes the first act and the noble gesture of renunciation in the final trio – these are memories of Lehmann to be cherished, for we shall not see them again soon.

LL Interview 1967

Here is a WBUR (Boston) interview with Lehmann broadcast on 27 January 1967. The program was called: Hall of Song: The “Met,” 1883-1966. The Lehmann portion of the broadcast begins at around 5 minutes.

John Amis on Lotte Lehmann

In 2021 John Amis put together a program of Lehmann’s singing called Lotte Lehmann: Vintage Years which can be found on YouTube.

LL sings Brahms to Koalas

LL Remembers Bruno Walter

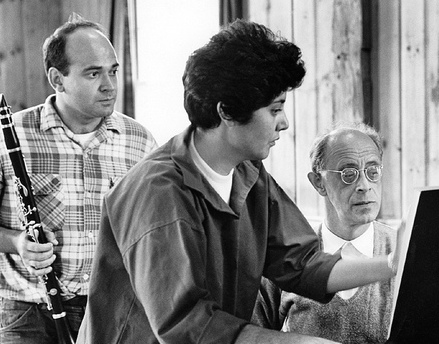

Pianist Remembers LL

Here is, Mitsuko Uchida, another pianist with fond Lehmann memories.

TIME Magazine Review

Music: More!

February 27, 1950

“One must take things lightly, holding and taking with a light heart and light hands—holding and letting go . . .”

These words of sage advice, sung to her mirror image by the aging Marschallin in Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier, are largely ignored by grand-opera stars. But to 61-year-old German-born Soprano Lotte Lehmann, who for 25 years sang them with unsurpassed eloquence, they have long had the weight of dogma.

Although her last singing of the Marschallin at the Metropolitan in 1945 brought her a 20-minute ovation, she decided soon afterward that it was time to “let go.” Two years ago she resolved to give up opera and operatic arias completely, sing only less strenuous lieder. She limited her concert tours to two months a year, spent the remaining ten months at her California home. When she wasn’t singing, she painted watercolors, fired ceramics of her own design in her home kiln, worked on her fifth book, Of Heaven, Hell and Hollywood.

Last week Lotte Lehmann, in the East for recitals and her first one-man show of paintings, went back on her resolution. To honor her good friend Richard Strauss, who died last summer (TIME, Sept. 19), and to mark her 50th Manhattan recital in a decade, she decided to sing once more the first-act monologues from her most famous role, the Marschallin.

To Lehmann fans the performance in Manhattan’s Town Hall had the air of a religious rite. They sat devout and mouse-quiet while the singer, dressed in sober black, her chestnut hair caught back in a plain bun, leaned gently against the curve of the piano. Without properties, costume or conspicuous gesture, Soprano Lehmann recreated the aging Viennese beauty with her oldtime fire and finesse.

For a minute after she sang her final words of wistful resignation, the audience was silent, then burst into seat-rattling applause. At intermission Lehmann had said, her eyes shining: “Fifty concerts! Aren’t you tired of me?” At recital’s end, the audience answered with cries of “More! More!” They brought her back for three encores.

By week’s end Lotte Lehmann had sung four sell-out recitals, closed her one-man painting show with most of her 63 paintings and ceramics sold. This week she was heading west for concert dates in Milwaukee and Chicago, then back home.

Someone to Listen to

On this 17 June 2025 that we’ve learned of the passing of Alfred Brendel, the following paragraph from his student, Imogen Cooper, seems appropriate:

Soon after my return to London I heard Alfred Brendel playing Schubert and Chopin at the Austrian Institute. It was fascinating. I went up to him afterwards and said, “I must work with you or I’ll die”. He answered, “Why don’t you live and come to Vienna?” The experience changed my life. He gave me time without parameters, we would work for hours on end, then we would sit down and listen to Furtwängler, Fischer, Cortot, the Busch Quartet, Kempff, Lotte Lehmann . . . It was an education, and an enriching experience. He was absolutely uncompromising about how he felt things should be, but also completely convincing, articulate and eloquent. It was a privilege and I learned a huge amount from him: how to listen, how to be aware of what I was doing, the meaning and shape of the phrase and not just the notes. It was a seminally important time for me and formed the basis of my adult music-making.

LL at the New Met

We have a short (interrupted) interview with Mme Lehmann (preceded by the First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson).

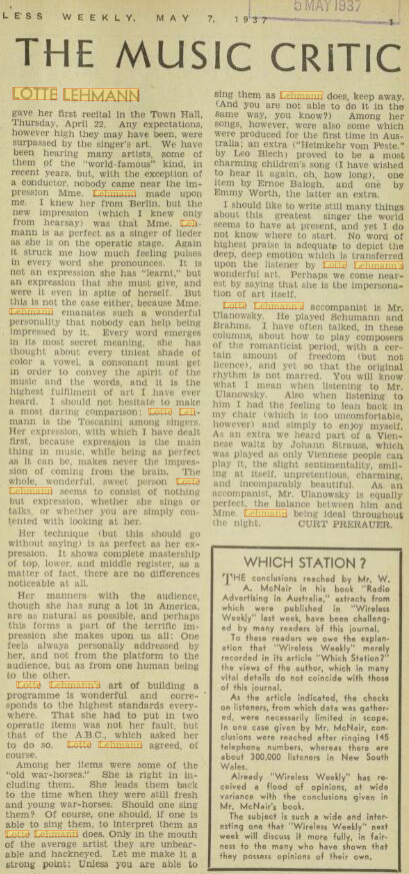

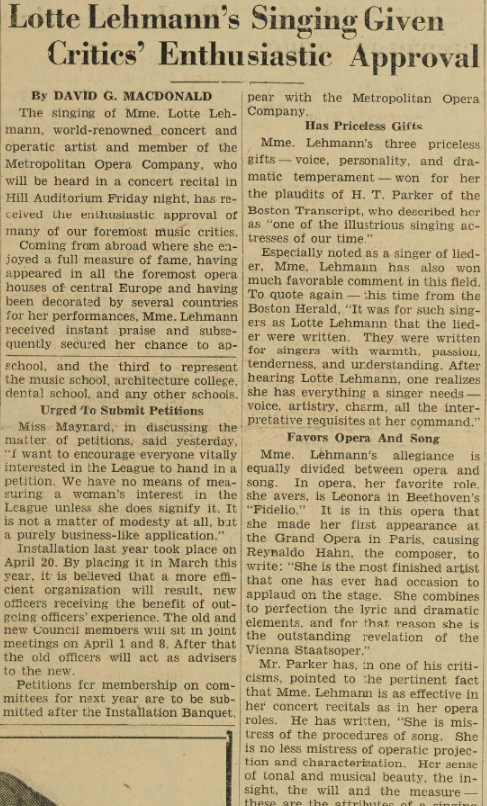

Enthusiastic Review

Lehmann’s agents and promoters could hardly have written a more positive review than this one from Sydney, Australia’s Wireless Weekly where Curt Prerauer wrote the following for the section called “The Music Critic”.

SYDNEY: Friday, May 7, 1937. THE MUSIC CRITIC

LOTTE LEHMANN gave her first recital in the Town Hall, Thursday, April 22. Any expectations, however high they may have been, were surpassed by the singer’s art. We have been hearing many artists, some of them of the “world-famous” kind, in recent years, but, with the exception of a conductor, nobody came near the impression Mme. Lehmann made upon me. I knew her from Berlin, but the new impression (which I knew only from hearsay) was that Mme. Lehmann is as perfect as a singer of lieder as she is on the operatic stage. Again it struck me how much feeling pulses in every word she pronounces. It is not an expression she has “learnt,” but an expression that she must give, and were it even in spite of herself. But this is not the case either, because Mme. Lehmann emanates such a wonderful personality that nobody can help being impressed by it. Every word emerge in its most secret meaning, she has thought about every tiniest shade of color a vowel, a consonant must get in order to convey the spirit of the music and the words, and it is the highest fulfilment of art I have ever heard. I should not hesitate to make a most daring comparison: Lotte Lehmann is the Toscanini among singers. Her expression, with which I have dealt first, because expression is the main thing in music, while being as perfect as it can be, makes never the impression of coming from the brain. The whole, wonderful, sweet person Lotte Lehmann seems to consist of nothing but expression, whether she sings or talks, or whether you are simply contented with looking at her. Her technique (but this should go without saying) is as perfect as her expression. It shows complete mastership of top, lower, and middle register, as a matter of fact, there are no differences noticeable at all. Her manners with the audience, though she has sung a lot in America, are as natural as possible, and perhaps this forms a part of the terrific impression she makes upon us all: One feels always personally addressed by her, and not from the platform to the audience, but as from one human being to the other. Lotte Lehmann’s art of building a programme is wonderful and corresponds to the highest standards everywhere. That she had to put in two operatic items was not her fault, but that of the A.B.C. [Australian Broadcasting Corporation], which asked her to do so. Lotte Lehmann agreed, of course. Among her items were some of the “old war-horses.” She is right in including them. She leads them back to the time when they were still fresh and young war-horses. Should one sing them? Of course, one should, if one is able to sing them, to interpret them as Lotte Lehmann does. Only in the mouth of the average artist they are unbearable and hackneyed. Let me make it a strong point: Unless you are able to sing them as Lehmann does, keep away. (And you are not able to do it in the same way, you know?) Among her songs, however, were also some which were produced for the first time in Australia; an extra (“Heimkehr vom Feste.” by Leo Blech) proved to be a most charming children’s song (I have wished to hear it again, oh, how long), one item by Emoe Balogh, and one by Emmy Worth, the latter an extra. I should like to write still many things about this greatest singer the world seems to have at present, and yet I do not know where to start. No word of highest praise is adequate to depict the deep, deep emotion which is transferred upon the listener by Lotte Lehmann’s wonderful art. Perhaps we come nearest by saying that she is the impersonation of art itself. Lotte Lehmann’s accompanist is Mr. Ulanowsky. He played Schumann and Brahms. I have often talked, in these columns, about how to play composers of the romanticist period, with a certain amount of freedom (but not licence), and yet so that the original rhythm is not marred. You will know what I mean when listening to Mr. Ulanowsky. Also when listening to him I had the feeling to lean back in my chair (which is too uncomfortable, however) and simply to enjoy myself. As an extra we heard part of a Viennese waltz by Johann Strauss, which was played as only Viennese people can play it, the slight sentimentality, smiling at itself, unpretentious, charming, and incomparably beautiful. As an accompanist, Mr. Ulanowsky is equally perfect, the balance between him and Mme. Lehmann being ideal throughout the night.

Good and Mixed Reviews

The first recently discovered review of one of Lehmann’s recitals is glowing with positive thoughts on many aspects of her singing. The second review includes some serious complaints but ends upbeat. The first has no attribution, the second only the initials: HTP.

Review of Recital in St. Louis on 13 Jan 1933

“One of the greatest personalities in the field of music made her first appearance in St. Louis last night when Lotte Lehmann, dramatic soprano, gave a song recital in Howard Hall, the Principia. The size and scope of her artistic gifts become apparent as soon as she starts singing but the impression deepens as song succeeds song until finally it has become a transfiguring experience. The voice by itself, with its depth, resonance and power, is galvanic in its effect, but the voice as an agent of her intellect and temperament brings an exhilaration that immediately makes all of the life about one more intense and more significant.”

Review of Recital in Boston on 8 or 9 March 1934

“…Mme. Lehmann’s singing of Brahms’ ‘Meine Liebe ist grün’, and his ‘Der Schmied’ …were examples of overpossession and over-projection to the detriment of voice and song. So also with Schumann’s ‘Ich grolle nicht’ which is one of her battle horses, to be ridden a little harder each time she mounts it. In a song that moves quick-paced, full-toned and in high emotion, Mme. Lehmann may hardly resist the temptation to force the note. There were as many songs in which she sang with an equal fineness of perception and tone, of matter and manner – – – say her simplicity with Schubert’s ‘An eine Quelle’; her musing grace with Franz’s ‘Für Musik,’ her light and tender humor with Wolf’s ‘In dem Schatten meiner Locken,’ her nostalgic melancholy with Strauss’s autumnal ‘Aller Seelen.’ In other pieces there were phrases and periods that she turned with apt and instant felicity; in which she gained both depth and sweep of tone – – – as in Wolf’s ‘Gesang Weylas’; once more in which she evoked passing images graphically; wrought them as well into an ever-expanding whole. The excesses and the shortcomings may stand as written, but the concert, by and large, was restoration of the art of lieder singing to a public that here or elsewhere in America may now seldom enjoy it.” H.T. P.

Review with a Cold

• Lehmann sang many recitals at Town Hall shortly before the “Farewell” one on February 16, 1951. Here’s a review of one of them that appeared on January 29, 1951.

Met Debut Review

• The “Parterre Box” celebrated the January 11, 1934 night that Lehmann made her Metropolitan Opera debut in what was called “the ideal Sieglinde” in Wagner’s Die Walküre with the review written by Leonard Liebling for the New York American:

Previously known here as a finished exponent of German Lieder in recital, Lotte Lehmann made her local operatic debut last evening at the Metropolitan as Sieglinde in “Die Walkuere.” Mme. Lehmann is no newcomer to the lyric stage, for at the Vienna Opera she has long been one of the adornments in Wagnerian and lesser soprano roles. Other European theatres and the late Chicago Civic Opera Company also are acquainted with Mme. Lehmann’s striking gifts in the realm of costumed song.

To tell the story of her achievement last night is to report a complete triumph of a kind rarely won from an audience at a Wagnerian occasion. The delighted auditors vented their feelings in a whirlwind of applause and a massed chorus of cheers. At the end of the first act Mme. Lehmann had half a dozen individual recalls and on every side one heard excited and rapturous comment. The stir made by the artist was in every way justified. Of statuesque figure and attractive features, Mme. Lehmann appealed to the eye as irresistibly as she wooed the ear. She has a full, rich voice, brilliant in the upper range and sensuously tinted in the middle register. It is a lyric-dramatic organ, ideal for the role of Sieglinde, and gives forth power as easily as it sounds the gentler accents.

More expressive, emotional, lovely singing has not been heard from any soprano at the Metropolitan for many a season, and, better still, Mme. Lehmann is musical and stylistic in the highest degree. A true Wagnerian artist whom the most diligent fault-finder would be estopped from faulting. In her acting, Mme. Lehmann interprets the impulsive, romanticist rather than the scheming woman who coldly plots the sleeping potion for her husband. Lissome, clinging, impassioned, here was the ideal Sieglinde to inflame Siegmund and sweep him to heroic deeds.

Reviews from the 1930s

La Scala?

• You can’t believe everything you read. This appeared in the Neue Freie Presse of 20 January 1924. In English: Tomorrow (Monday) Lotte Lehmann‘s single concert [we’d call it a recital] at 7pm. At the piano: Professor Ferdinand Foll. Miss Lehmann appears as Lieder singer before the Vienna public for the first time in several years. Her program contains songs of Brahms, Schumann, Cornelius, Marx, and Strauss. In this concert, Miss Lehmann takes leave of the Vienna public for a longer period of time, because only a few days later she travels to Italy for several months, where she first appears as a guest singer for two months at La Scala, Milan. Remaining tickets…..The recital information is correct, but Lehmann didn’t sing on those dates at Italy’s La Scala. Rather, in this case, she traveled to Berlin, first to record on 13 February and then to sing opera there with Georg Szell, among other conductors at the Berlin Staatsoper, where she remained, making records and singing opera until 21 May 1924 the date she sang her first Marschallin in London under Bruno Walter’s direction. She continued singing opera (Ariadne auf Naxos, Der Rosenkavalier and Die Walküre), not returning to Vienna until the next season when on 9 September 1924 she sang in Faust. As usual, many thanks to Peter Clausen for the clipping. P.S. Lehmann did eventually sing a recital at La Scala, but in 1935.

Review of Schumann Songs 1943

• The following review that speaks for itself has come to my attention. Take the time to read it through to understand the level of artistry that Lehmann had reached by 1943.

New York Times 25 January 1943

LEHMANN IS HEARD IN SCHUMANN SONGS

Soprano is assisted by Paul Ulanowsky in Program at Town Hall

By Olin Downes

A very distinguished recital of songs and song cycles by Robert Schumann was given by Lotte Lehmann yesterday afternoon in Town Hall. The capacity of the hall was brought out by an exceptionally attentive and appreciative audience days in advance of the event. There was no fuss about that either. The audience was practically all seated when the singer came in. The program began by Mme. Lehmann’s inviting the audience to sing the national anthem with her. Then she and her excellent accompanist, Paul Ulanowsky, began their task of communicants with the songs.

These were sung with a matchless simplicity, with an art that concealed an art now fully developed and shorn of every excrescence or superfluity of style, and the interpretation proceeded directly from the heart.

Mme. Lehmann sang these reveries and avowals with a fineness of style and a sense of proportion that had no slightest savor of exaggeration or less than utter sincerity, and her performance said plainly that if this was sentimental the audience could make the most of it. She believed what she sang. She herself was moved by it.

The “Dichterliebe” cycle permitted a wider range of expression and a greater variety of color. But the same simplicity, the same warm poetry and perfect proportion remained. Nor are the postludes of the piano to be forgotten. That is to say that there was complete unity of intention between the two performers, and that Mr. Ulanowsky with rare taste and sensibility completed the poetic thought of interpreter and composer.

One remembers those earlier years when Mme. Lehmann’s own nature swept her away and this resulted in prodigal and at time explosive outburst of tone, or disproportionate emphasis of phrase. All that is of the past. The thoughtful expenditure and shaping of tone, the maximum of communication with the minimum of effort, an intensity of emotion that requires no noisy heralding spoke more eloquently than any description could do.

Mood was established so completely that there was comparatively little demonstration till the end of the recital. For that matter the two cycles were sung without opportunity for applause between the songs that make them. But it is doubtful if in any case there would have been such a sign. There was the rapport between the artist and her listeners made possible by her achievement and also by the proportions of the hall. At the end the audience was loath to leave. Mme. Lehmann wisely refrained from an encore. To the best of her ability she had done a complete thing, and what she had done will long be cherished by those who heard her.

• From the Pariser Tagezeitung of 8 April 1938, Peter Petersen has sent the following article, which I translate: LOTTE LEHMANN SINGS NO MORE IN THE THIRD REICH; Lotte Lehmann, the great singer famous even at the Casino Theater in Desuville, who yesterday returned to America, stated the following to a French journalist: “No, I haven’t been driven from Germany. I am Arien and so is my husband.”

“Why are you leaving your homeland, you who just last year, was celebrated as no other artist, in Fidelio under the direction of Bruno Walter and Toscanini; you who give the artistic fame to the Vienna Opera and who experiences such triumphs from your too seldom Paris appearances?”

“Why? Because I don’t feel free in my homeland, because I can’t live freely and have the right to choose songs by Mendelssohn, Hugo Wolf or [Joseph] Marx. This is why I have left my homeland, but I have left freely…Certainly, nothing in the world is more important than freedom. Thus, I will seek American citizenship.”

Bad Reviews

• In the various Lehmann biographies one can read glowing reviews of Lehmann’s performances. I’ve finally found one full of negative comments and a second one with mixed thoughts. These are English critics. The first, acknowledges Lehmann’s success at Covent Garden and the enthusiasm of the Queen’s Hall audience (probably of 25 Feb 1930), as well as the “insinuating beauty of her voice–perhaps the loveliest one has ever known” and “her quick and warm response to poetic suggestion.” Then he begins with his problems: “There was a streak of the maudlin in her programme that proved rather too much for a modern English audience. We accept nothing more gladly than German songs from Mme. Lehmann, for we know the sort of thing she excels in, but her scheme to-night would have been better for a little more spice. One or two Schubert songs, Brahms in one of his irascible moods, or some of the acid of Hugo Wolf would have made all the difference, and none of these masters was represented at all. Beethoven sounded a little meagre, though the two “Egmont” songs were an interesting revival, and Schumann was shown in his wan and tearful manner, except in the enthusiastic “Frühlingsnacht,” which surged magnificently to the singer’s most jubilant tones. It was this song one wanted to hear a second time, not the once incredibly overrated “Ich grolle nicht,” which nowadays seems not so much a song as a smear. For the Liszt songs there were two excuses–that they really represented the composer adequately, if unflatteringly, and that much of their cloying perfumery was made tolerable by the persuasive beauty of the singing.” Of the same performance another critic wrote, “Last night she really convinced a large audience that she is a brilliant exception to the general rule that opera singers are not at their best away from the stage. She does not sing Lieder as if they were dramatic scenes, but with her perfect feeling for curve and phrase she sings those German sentimental love songs that are so dear to the heart of the Teutonic maiden with a rare lyric eloquence. Her generous programme last night composed songs by Giordani, Monteverdi, Gluck, Beethoven, Liszt, Marx, and R. Strauss. Naturally certain songs in her list were more closely suited to her ability than others, but to them all she brought a clarity and precision of technique, an earnest approach, and a sensitive understanding which were matched only by the charm and spirit of her delivery.” He goes on to list the songs he likes and then: “…she was not quite so successful with the Beethoven group and she certainly should not sing ‘Freudvoll und Leidvoll’, [which the above critic praised!] which she screams at the top notes.”