On this page I want to introduce you to Frances Holden, who was Lehmann’s companion from 1938 until her death in 1976. Below, you’ll read what Judy Sutcliffe, Beaumont Glass and even Lehmann herself had to say about this remarkable woman. Here is a page of photos of Holden. This is an audio of Holden speaking. It’s soft, but that’s how she spoke. We have a letter that Holden wrote to critic Desmond Shaw-Taylor on aspects of a Lehmann biography with which she disagreed. Holden on Lehmann bio

Here’s a link to the Frances Holden chapter in the second volume of the Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy (originally an iBook).

I met Lehmann’s companion, Frances Holden, in 1962, when I was driving my friend to their house for his lessons. Though Lehmann was the famous one and the reason that we drove there, Frances was certainly a presence. She didn’t get in the way of the lessons, but she was there for anything else that was needed. It was a balance between Holden and Lehmann.

At first I was intimidated. She was rough and in charge, but I knew that she was there to organize things for Mme. Lehmann. My memory is vague otherwise, until after Lehmann’s death.

I visited Orplid in 1977, less than a year after Lehmann had died. Frances was ill and only spoke to me through a window. She knew who I was, she’d written to me, very kindly, after Lehmann’s death. But she wanted to be left alone and was mostly afraid that I was there to claim some of Lehmann’s affects (which wasn’t the case). She seemed less defensive when she knew that I was just there to say “hello” to her.

When I began, years later, to work on the Lehmann archive at UCSB, I always stopped and visited at Orplid. Frances didn’t like long visits, but I always grew fascinated with the rare recordings, which she let me dig through. Sometimes she’d go on with her own things and just let me alone.

When the work on the Lehmann Centennial began in 1987 I was with Frances a lot. She was crusty and at the same time friendly. She wanted the best for Lehmann and she didn’t allow anything else. But she was not unreasonable. And she was knowledgeable: about Lehmann’s life, about the MAW, about UCSB and the staff there, and about practical things, the Lehmann bio, and all aspects of the proposed Centennial. She and I locked horns on many things, but when at the Centennial I gave my talk on my Lehmann Discography and played Lehmann recordings, she cried.

In the aftermath of the Centennial I was often at Orplid and working with Frances, especially to use the recordings for the planned RCA CD. We also worked together on the Lehmann archive at UCSB for she was close with Joe Boiseé, who was the head librarian there. I remember being at Orplid when he was there with Frances. There was an obvious bond between them.

Frances obviously willed her estate to the MAW. They’ve named a garden there after her and it’s through her funds that they became an all-scholarship school. She’d be proud.

Now, I’ll let Judy Sutcliffe tell some of her own Frances Holden stories.

JUDY SUTCLIFFE—A COLLECTION OF OLD MEN: SCOTCH & SYNCHRONICITY (The complete book “A Collection of Old Men” is available from Seven Gables Press, PO Box 42, Mineral Point, WI 53565 for $17.50 plus shipping $2.50.)

I was helping Frances Holden with the booksale on the seventh floor of the UCSB library in Santa Barbara. Frances, who was in her late 80s, had run the sales of donated books for many years. Consequently, she had first choice of purchase. She was also a major donor to the library and could do as she pleased. She had ten rooms of floor-to-ceiling books in the old rambling house she owned on several acres above the ocean in Hope Ranch. I had second choice. I amused myself looking for German books with attractive type and illustrations.

“Handle this, will you?” Frances said to me. She had her eye on a couple students and the possibility of selling them some slightly outdated travel books. She was a small-boned woman with an indeterminate, thickened waist and short, straight, unmanageable hair, rarely seen in any mirror. She had a gruff looking, squarish face and a brusque voice to match…

And Frances was no spring chicken, either, though she drove like one. Her old ivory Buick had one big slick leather seat across the front and no seat belts. I never felt safe in that car. “Stop worrying,” she’d growl. “No one would dare hit this car. It’s built like a tank.”

After we counted up the book sale take, we headed for her house in her car. As she barrelled that Buick down the entrance ramp onto the freeway, her tiny feet in sensible shoes barely reaching the pedals, she ripped off her glasses and handed them to me. “I can’t see anything out of these,” she complained. “Can you clean them off?”

I was relieved when we turned into her driveway and pulled into the old garage draped in bougainvillea. My little Volkswagen was parked nearby. We sat outside in her porch swing for a while, shaded by clusters of trees and rampant vines in a soft late afternoon glow. Frances looked at me. “How about a hotdog and some scotch?” she inquired.

I lied and said I wasn’t hungry. “Maude!” she yelled towards the kitchen, and her housekeeper appeared, nodded, returned with scotch for Frances, red wine for me.

A terra cotta bust of Lotte Lehmann on a pedestal caught the dappling shadows of early evening. Lotte was the German opera singer Frances had lived with for decades in this house, among these extensive gardens, until her death some years ago….

Many thanks, Judy for that.

Judy Sutcliffe also wrote a long article on Holden, Glass, and the impression that Lehmann made on her (Judy). Sutcliffe on Holden et al.

Now the obit: Frances Holden; Studied Psychology of Genius

August 25, 1996

Frances Holden, 97, who studied the psychology of genius, particularly that of classical musicians. A native of New York City, she was educated at Smith College and Columbia University. Holden was the first woman appointed to the psychology faculty at New York University, where she taught for 12 years. During her research, she befriended German soprano Lotte Lehmann. After Lehmann was widowed in 1939, the soprano shared Holden’s Santa Barbara home until her death in 1976. The two women christened the home Orplid for a dream island retreat described in “Gesang Weylas” by Hugo Wolf. They played host to internationally celebrated musicians including Arturo Toscanini, Bruno Walter, Thomas Mann, Rise Stevens, Dame Judith Anderson and Marilyn Horne. Holden was a major fund-raiser for the UC Santa Barbara Library and was active in the Music Academy of the West in Montecito. On Aug. 10 in Santa Barbara.

From Lotte Lehmann, A Life in Opera and Song by Beaumont Glass, here is the beginning of the relationship between Lehmann and Frances Holden:

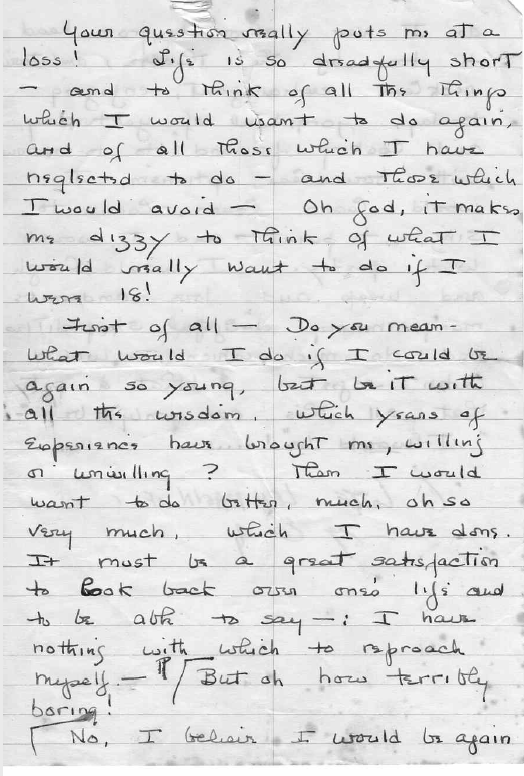

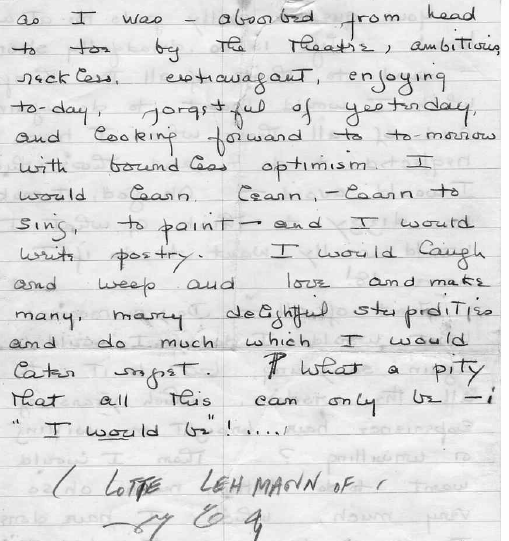

…Lotte was deeply depressed because two critics, whose opinions she valued, wrote negative notices. Frances Holden, whom she had not yet met, had heard through friends at the Constance Hope agency about Lotte’s distress and wrote to reassure her, and to reproach her for taking those reviews so seriously. Lotte’s reply expressed her feelings in a most revealing way. Her English was not yet as fluent as it later became. These were her words:

Your lovely letter has given me much joy. You must understand me and not blame me, that I hear too much what everybody is talking… I am always afraid to be an arrogant “prima donna,” who thinks that everything is well done… I know artist friends, who are very intelligent, but without any objectivity for themselves. I want to be critical with myself. I know that often I spoil my life, but it is my nature, I can nothing do against it…

The Tosca performance was so bad, it was like under a bad luck. But I myself have given all my heart, have soon forgotten that I was fighting already against a overworked weakness of my voice. When I saw next day the critics of Downes and Chotzinoff, I was so depressed, because I have said to myself: “I have felt the Tosca, I was the Tosca. And they have not felt it with me. Therefore perhaps I was bad. I have not had the artistic power to show what I was feeling.” Always I search the fault in myself—that is perhaps the fault…

Oh, I was feeling miserable. And then came the trouble with my voice and that the Director in Metropolitan has not believed my illness [Lehmann had been forced to cancel a Tosca in New York and two performances, Walküre and Lohengrin in Boston]. He thought I have a caprice… And my doctor has not protected me… I never will forget those awful two days… But now I am recovering, and my voice seems all right again. And I will find myself, my believing in myself—in lovely holidays on the French Riviera.

And Glass writes of their further relationship:

Viola there was an unknown young woman who would later play a leading role in Lotte’s life. Dr. Frances Holden, Assistant Professor of Psychology at New York University, was deeply enthralled, though less ostentatiously than Viola, whose ecstatic gesticulations during Lehmann’s singing distracted and disturbed those who were sitting behind her. Dr. Holden was at work on a scholarly study of the psychology of genius. There before her, it seemed to her, stood the living embodiment of genius. From that day on, she made every effort to arrange her teaching schedule so that she could attend every possible Lehmann performance, in opera as in recital, in New York or out of town.

Lehmann gave her something precious she had never known before. In her gratitude, Dr. Holden sent welcoming flowers, without a card, to nearly every concert. But it was more than two years before she wrote to Lotte, to ask for information about her autobiography. It was still incomplete; but excerpts from the early part had already been printed in The New York Herald-Tribune. She did not try to meet Lotte. She wanted to study Lehmann the artist, not Lotte the woman.

The artist, however, was not so easily separated from the woman. Lotte was always curious to meet her especially devoted fans. Her first letter to Frances was to thank her for flowers; then, in the letter quoted earlier in this chapter, for kind words about her Tosca at the Met. A third letter brought them closer together, though they had not yet met. Lotte had heard, through another fan, that Frances had lost her mother. Here are her touching words of condolence (originally in German):

Dear Miss Holden — to my sincere thanks for the welcoming greeting of your lovely flowers I must add today the expression of my heartfelt sympathy….Please believe me that I sincerely and warmly share what you are feeling. Just two years ago today I lost my beloved mother—I know how hard that is, and how infinitely sad you must be now.

In our lives we go through many dark hours—and one of the most painful and fateful is when we have to bury our mother. That is no empty figure of speech! With her death I lost the feeling of “home.” And even if time heals all wounds, that scar will never stop hurting….

Finally Lotte decided to invite Frances to Thanksgiving dinner. It was a rather Austrian version of Thanksgiving. The turkey was served already cut in little slices, swimming in some exotic sauce. The table conversation was in German, too fast to follow. Lotte found Frances a bore. Frances was appalled that a high priestess of song could laugh at an off-color joke. The occasion was no overwhelming success. But from such an inauspicious beginning a unique and beautiful friendship was born.

More from Glass:

Frances Holden was intelligent, deep, and dependable. She could do almost anything and do it well. Once a neighbor who had locked herself out asked Lotte if she could use her phone to call a locksmith. “That’s not necessary,” Lotte told her, “Frahnces will get your door open.” And of course, “Frahnces” did, scaling a wall and scrambling through a little window.

Next, Glass writes:

Before he died, Otto had told Lotte that of all their friends the one she could best depend upon would be Frances Holden. Otto had always liked her especially. He knew she would be able to take care of Lotte without making any emotional demands upon her.

Lotte needed someone to lean on, to be there for her. She hoped that Frances could be that person. But Frances was reluctant to come so close to the woman Lotte Lehmann, much as she revered Lotte Lehmann the artist.

Here is a portrait of Frances Holden by Lotte Lehmann:

She comes from a family totally dissimilar to mine: she is a regular Yankee, through and through; her family belongs to one of those that came over on the Mayflower. For twelve years she was a professor of psychology at New York University. With an unquenchable thirst for knowledge, she lives in the world of books. We are so different that all my friends—and hers too—predicted that we would part as bitter enemies after two weeks at the most.

They all guessed wrong: since the death of my husband in 1939 we have lived together in the most beautiful harmony.

Perhaps it is true that opposites attract. But in our case it is more than that often-cited theory. For we do have much in common: a great love of nature and of animals. A certain creative urge that seeks to explore and to conquer new areas of art. And best of all, we try to season life with a dash of wit and to overcome our troubles with humor….

Through the illness of a very dear mutual friend it happened that Frances came to stay with me “for a while”—and that extended till today. She is quite a wonderful person. Her character is almost faultless, I would say. It is not always easy to live with somebody so perfect. Or better said: it wasnot always easy. Now, after all these years, I am accustomed to it. I know that when we have an argument about the right or wrong of something, her decision is generally right….Our life together is based on understanding of each other, and may God grant that it will continue that way.

In a letter to her pianist Ernö Balogh, obviously in answer to one of his questions, Lehmann wrote: “Of course I am with Frances! I shall be so till the end of my life! She is the most wonderful and understanding friend anybody could wish to have. What a strange question!!! “