Lotte Lehmann enjoyed her third career just as much as she did her first two. Kathy Brown’s 2012 book Lotte Lehmann in America: Her Legacy as Artist Teacher, with Commentaries from Her Master Classes thoroughly describes Lehmann’s teaching methods. Presented here are audio and video documents of her teaching, and examples of her students’ singing, as well as comments on their teacher.

Lotte Lehmann enjoyed her third career just as much as she did her first two. Kathy Brown’s 2012 book Lotte Lehmann in America: Her Legacy as Artist Teacher, with Commentaries from Her Master Classes thoroughly describes Lehmann’s teaching methods. Presented here are audio and video documents of her teaching, and examples of her students’ singing, as well as comments on their teacher.

In the following video excerpt, Lehmann reveals the secret to her great success, in both Lieder and opera singing. There are great artists who don’t necessarily subscribe to this philosophy, but Lehmann obviously did and she’s suggesting to her students that they should consider the same principle.

Without singing a note, Lehmann demonstrates how the singer can respond to a piano introduction. Notice that the hands don’t hang limply down at the side of the body, and you sense that she is hearing the importance of every note. But really, there isn’t much motion at all. The singer listens to the piano and reacts naturally.

Lehmann demonstrates—at the age of 73 and without much voice—the various elements of the Robert Schumann Lied, “Ich kann nicht fassen, nicht glauben” (I can’t understand it, not believe it) from his cycle, Frauenliebe und -Leben. This is the moment in the story at which the young girl knows that he loves her.

The mysterious and pleading quality that Lehmann suggests are found in the words of one of Goethe’s most famous lyrics, “Kennst du das Land.” Here are the words she quotes, in English translation: Do you know the land where the lemon trees blossom? Among dark leaves the golden oranges glow. A gentle breeze from blue skies drifts. The myrtle is still, and the laurel stands high. Do you know it well?

A recitative is that portion of an opera in which a lot of information is offered, without the aid of much melody. It’s usually overlooked, because singers want to get to the aria. Here, Lehmann takes the time to demonstrate the words of the Countess, in the Marriage of Figaro. Though Mozart set Da Ponte’s Italian words, it was the tradition in German-speaking lands to sing everything in the language of the audience. And Susanna doesn’t come. I’m anxious to know how the Count took her proposition. The scheme seems too bold to me, and to a husband so wild and jealous! But what harm is there? Changing my clothes with those of Susanna, and hers with mine… shielded by the night… Oh heavens, to what a humiliating state I am reduced by a cruel husband, who, after marrying me, with an unheard of mixture of infidelity, jealousy and scorn, first loved, then offended, and at last betrayed me, now makes me turn to one of my servants for help!

The student has performed the most famous aria from Weber’s Der Freischütz. Lehmann illustrates with her body and face, a response to the music and situation when there’s no singing. The character Agathe is impatiently waiting for her boyfriend, who she hopes has won the shooting contest.

In the following Brahms Lied, Lehmann has said that the 17th-century poet Paul Fleming’s words of the infatuated lover are unimportant and must just tumble out. Despite this admonition, she demonstrates with her usual clear diction, but “sings,” as usual during her teaching years, an octave below the soprano key.

O Schönste der Schönen benimm mir dies Sehnen,

Komm, eile, komm, komme, du süße, du fromme!

Ach, Schwester, ich sterbe, ich sterb’, ich verderbe,

Komm, komme, komm, eile benimm mir dies Sehnen,

O Schönste der Schönen!

Oh fairest of the fair, free me of this longing,

Come, hurry, come, you sweet, innocent!

Ah, sister, I die, I die, I perish,

come, hurry, come, free me of this longing

Oh fairest of the fair!

LL with pet 1930

A New York City critic voiced a negative opinion when Mme Lehmann sang an “All-Brahms” Town Hall recital. Today we would welcome such a chance to appreciate the many-sided nature of Brahms Lieder. Lehmann could milk the tragic songs, and make one laugh at the light-hearted ditties. Luckily many of the acetates of these recitals have been located, and the serious Lehmann fan can find them available in the box set that Music & Arts released.

Below, Lehmann discusses the involvement of the whole body when singing, but cautions against extraneous or meaningless motion. I have witnessed Lehmann demanding of a student the most sensitive response to the words, psychological subtext, and complete engagement from the eyes to the feet.

In this demonstration of the Robert Schumann Lied, “Schöne Wiege meiner Leiden,” Lehmann illustrates the broad spectrum of responses to each line of this strophe. She doesn’t have the words in front of her and makes up a few as she goes along.

Doch du drängst mich selbst von hinnen,

bittre Worte spricht dein Mund;

Wahnsinn wühlt in meinen Sinnen,

und mein Herz ist krank und wund.

Yet you yourself pushed me away from you,

bitter words at your lips;

Madness filled my senses,

and my heart is sick and wounded.

Video: Schoene Wiege meiner Lieden LS

Classical singers often think that the smooth singing they seek can be obtained by connecting the notes with a slide. Here Lehmann observes that this habit makes a song sound sentimental and must be avoided. In the past, many singers, including Lehmann, used this portamento effect in their performances, weakening their presentation.

This demonstration of a Brahms song allows us to hear and see just what made Lehmann so appealing in her recital performances. Each phrase of Ludwig Uhland’s poem elicits a reaction from her, whether vocal or physical, and this response doesn’t cease when she’s finished singing the words.

Das tausendschöne Jungfräulein,

Das tausendschöne Herzelein,

Wollte Gott, wollte Gott, ich wär’ heute bei ihr!

That thousand-times beautiful girl,

That thousand-times beautiful little heart,

Would to God, that I could be with her today!

In this brief scene from Lohengrin, Lehmann summons up all the evil inherent in Ortrud’s character and shows that the whole body must engage in the thought being expressed in singing.

Könntest du erfassen,

wie dessen Art so wundersam,

der nie dich möge so verlassen,

wie er durch Zauber zu dir kam!

Have you never grasped

that he of such mysterious lineage

might leave you in the same way

as by magic he came to you?

Video: Your Eyes Don’t Sing

Here are some individual songs and arias with Lehmann teaching their interpretation at Cal Tech in Pasadena in 1952. Auf einer Wanderung Heimliche Afforderung Zueignung Du bist der Lenz

Lehmann’s Students

Grace Bumbry, Lehmann, Chieko Sakata, Douglas Miller, Luba Tcheresky, and Leslie Guinn in Lehmann’s Metropolitan Opera box, 26 March 1958.

Many of Lehmann students went on to world fame and others to highly successful careers. The most famous of her students, Marilyn Horne and Grace Bumbry, specialized in opera. Horne became an excellent bel canto singer, who, though she sang the verismo title role of Carmen, concentrated her talents in the coloratura characters found in operas by Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini. Bumbry, like Horne, sang in major opera houses throughout the world, but lived in Europe. Her fame rests on the dramatic mezzo soprano roles associated with Verdi. Both Horne and Bumbry sang at the White House and were recipients of the Kennedy Center Honors award. One can easily buy CDs and DVDs of these women in their prime as opera singers. Their work as Lieder singers is less well known. Beaumont Glass is Bumbry’s pianist in Wolf’s “Anakreons Grab.” Lehmann sings Anakreons Grab Bumbry sings Anakreons Grab Horne sings Wagner’s Träume from the Wesendonck Lieder

Other exceptional pupils included Benita Valente and Mildred Miller, who both appeared extensively at the Metropolitan Opera and also sang recitals. Valente was lauded for her Mozart and Handel singing, though she also sang certain Verdi roles. Her work in chamber music settings earned her the honor of having several pieces written for her voice and string quartet. Cynthia Raim is her pianist for Die Nacht

Miller sang mainly at the Metropolitan Opera from 1951—1974, often associated with the pants roles of Octavian, the Composer, Nicklausse, and Prince Orlofsky. She sang an amazing 338 performances there.

She tells of the first time she heard Lehmann and mentions the Brahms Lied, “Mein Mädel hat einen Rosenmund,” which you can hear Lehmann sing. Then Miller speaks of the importance, for her, of the Schumann Lied, “Aus der Heimat…,” which she sings with John Wustman, piano. Lehmann was so proud of her that she flew to New York when Miller made her Town Hall debut.

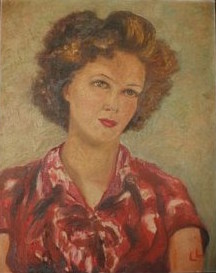

Mme. Lehmann with Mildred Miller

Mildred Miller Speaks; Lehmann sings Mein Mädel hat einen Rosenmund; Mildred Miller sings Aus der Heimat from Liederkreis Op39

Lehmann’s final pupil was Jeannine Altmeyer, whose excellence in Wagner operas has been preserved on DVDs. Her European performances included Salzburg, Covent Garden, and Bayreuth. After her retirement, she recorded a Lied (Schubert’s “Gretchen am Spinnrade”) that she’d studied with Lehmann. Val Underwood is her pianist. Altmeyer sings Gretchen am Spinnrade

Carol Neblett studied privately with the then-elderly Lehmann. She had a worldwide career as an opera soprano and her recording of Korngold’s Die tote Stadt became a classic. She had great success at the New York City Opera, and sang as well at the Metropolitan Opera. Not famous for her Lieder, she did perform a tribute recital to her teacher for the Lehmann Centennial held at UCSB in 1988. Korngold excerpt; Neblett speaks

Luba Tcheresky was an alumna of Lehmann’s Music Academy of the West master classes for three years. She sang opera for a short time in Europe and in many genres in the United States. As with most of Lehmann’s students, she taught, in this case privately, for many years in New York City. Here’s a live performance of her singing Schumann’s “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai” with Beaumont Glass, piano. Tcheresky sings Im wunderschönen Monat Mai Luba Tcheresky Speaks

One of Lehmann’s most serious students was the Canadian soprano Shirley Sproule, who studied at the MAW both in the summer seasons, as well as the short-lived winter ones. She enjoyed a minor career in Europe and taught later in Canada and the U.S. Sproule was almost 80 years old when she recorded her tribute, “Der Himmel hat eine Träne geweint” (Heaven Cried a Tear) by Schumann with Paula Fan, piano. Sproule sings and speaks

Evangeline Noël Glass studied at the MAW, appearing on the VAI opera and Lieder master class videos. She sang in such classes in Europe as well, where she taught with her husband, Lehmann’s biographer, Beaumont Glass. Evangeline Noël’s Lehmann Memory Beaumont Glass Speaks

The male students among Lehmann’s master classes and private lessons didn’t achieve the same fame as the women, but were able to enjoy satisfying careers. William Cochran’s beautiful tenor voice is heard here as Siegmund. The Salt Lake Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Maurice Abravanel (another MAW connection). He sang in major opera houses in the United States and at Covent Garden, and opera companies in Frankfurt, Munich, Hamburg, and Vienna. William Cochran sings from Die Walküre

William Olvis was born in Los Angeles. His talents carried him from Hollywood to New York, on to Europe, and back to New York, where he performed with the Metropolitan Opera. The excerpt is from the movie based on the life of Sigmund Romberg called Deep in My Heart (1954). But Olvis also sang opera, as you’ll hear in the “Gewitter und Sturm” aria from Der fliegende Holländer. William Olvis sings the Serenade Olvis sings Gewitter und Sturm

Harve Presnell had a very successful career in Broadway and in Hollywood movies, most notably The Unsinkable Molly Brown. Presnell had sung with orchestras and opera companies, but his fame was due to his work in musical theatre and later as a character actor in films. We have a chance to hear him “classical” in the excerpt from Orff’s Carmina Burana, conducted by Eugene Ormandy. Presnell sings excerpt from Carmina Burana: Omnia Sol temperat

In the following tracks we can hear Norman Mittelmann talk about studying with Lehmann and then hear him sing Schumann’s “Die beiden Grenediere” with Gale Enger on piano recorded in 2005, long after he’d retired. Mittelmann began singing opera in Lehmann’s productions at the MAW. In 1958 he made his debut in his Canadian homeland and later sang in major European and North and South American opera houses. Mittelmann made his Metropolitan Opera debut in 1961 and sang there for the next 20 years. Mittlemann speaks about LL Mittlemann sings Die beiden Grenadiere

One of the students for whom Lehmann held the most hope was Lincoln Clark, who expanded his career, and gradually left singing behind. We’ll let him tell the story. Lincoln Clark’s LL Tribute

The fame of Lehmann’s student Lotfi Mansouri was not at all as a singer, but as a director of operas. His work with the Canadian Opera Company, as well as the San Francisco Opera brought him deserved great recognition. Mansouri was responsible for the introduction of surtitles, which have done so much to make opera successful. His memories speak fondly of his work at the Music Academy of the West. Lotfi Mansouri Speaks About LL

There are many singers who worked only peripherally with Lehmann. Marni Nixon is most famously known as the singing voice behind the star in the movies The King and I, West Side Story, and My Fair Lady. But her singing and acting career spanned Broadway, opera, concerts, and recordings both in avant-garde and standard repertoire. Her memory of working with Lehmann includes one under-appreciated element of singing: subtext. At the age of 75 she recorded Schoenberg’s cabaret song “Galathea” with pianist Thomas Bagwell. A nice further connection: they recorded in New York’s Town Hall, where Lehmann felt so at home. Marni Nixon Speaks About LL Nixon sings Galathea

Long before Lehmann taught at the Music Academy of the West, she coached many singers, including Jane Birkhead, Eleanor Steber, Risë Stevens, Rose Bampton, Nan Merriman, Dorothy Maynor, Anne Brown (the original Bess in Porgy and Bess), and Jeannette MacDonald. Birkhead Remembers LL

During Lehmann’s Music Academy of the West years, and privately thereafter, star students included those mentioned above, as well as Karan Armstrong, Judith Beckmann, Kay Griffel, and Maralin Niska.

Established singers who valued Lehmann’s coaching included Hermann Prey, Gérard Souzay, Hilde Güden, Janet Baker, Thomas Moser, Rita Streich, Raimund Herincx, and Alberto Remedios.

LL coaching Crespin

Lotte Lehmann was the director/advisor of the 1962 Der Rosenkavalier for the Metropolitan Opera. For that occasion she coached the famous cast of females that included Régine Crespin as the Marschallin, Anneliese Rothenberger as Sophie and the reluctant Hertha Toepper, Octavian.

We look with some dismay at these names, because most of them, sadly, have already died.

Town Hall Master Class for Manhattan School of Music

Look at the smile on Mme Lehmann’s face as she acknowledges Paul Ulanowsky who has played for the master class. I believe that she would have been more than satisfied to have enjoyed the one career of teaching. Manhattan School of Music students in the 1965 Town Hall master class included: Marc Vanderwerf, Barbara Blanchard, Celina Kellogg, and Glenda Maurice. In the first audio track you’ll hear Lehmann set the boundaries for her teaching. LL Interview Teaching Interpretaton Not Imitation Then you’ll hear her teach a master class student the light Hugo Wolf Lied “Du denkst mit einem Fädchen mich zu fangen” (You think you can catch me with a thread). LL MC Du denkst Then, you can hear Lehmann sing the Lied in a recording with Paul Ulanowsky, pianist. Du denkst mit einem Fädchen mich zu fangen

Lehmann gave her pupils meaningful singing experiences that would open possibilities of expression. Then how does one come to such a famous, celebrity teacher and not imitate? She knew this and hoped to provide an environment in which their skill and knowledge would unite with the suggested interpretation needed to bring life to a song or aria. Anyway, how much can a student learn in a few minutes? Lehmann’s information or exploration could open up a revelation of, for instance, sub-text, humor, specific poetic or libretto words or phrases that can make a song or aria come to life. Sometimes the student would have to take Lehmann’s suggestions home and work on them. That is what Lehmann expected. Here’s a video of Lehmann teaching: You Must BeThe Person

Listen to the following Lehmann students speak (or sing) about their experience. Lois Alba Speaks Alice Marie Nelson Speaks Nelson Sings Von Ewiger Liebe Marcela Reale Sings Solo E Amore

At this writing Lois Alba is still actively teaching in Texas. Alice Marie Nelson sang “Von ewiger Liebe” (Of Eternal Love) by Brahms with Warren Jones, piano. She is still giving recitals. Marcella Reale who still teaches in Japan, came out of retirement to record this one Puccini song with Roberto Negri, the pianist. The song is “Sole e Amore” (Sun and Love) and it may remind you of La bohème, which Reale often sang.

When teaching, Lehmann enjoyed having the young students laugh at any reference to carnal love. She always felt that they were too prudish and often missed the essence of a poem or aria.

In the following video taken at the end of a master class, Lehmann admits to her joy in singing through her students, and after some applause bids her pianist, Gwendolyn Koldofsky, to share the bows. Koldofsky was a wonderful pianist, able to follow the wishes of a student without missing a note. She taught for many years the piano accompaniment classes at the University of Southern California. Many of her students have become sought-after pianists. Here’s a video: LL Sings Through Her Students

The following recordings are from the Caltech master classes of 1952. LL MC Strauss: Die Nacht LL MC Torelli: Tu Lo Sai LL MC Verdi: Iago’s Credo LL MC Brahms: Immer Leiser LL MC Debussy: La flute de Pan LL MC Maman dites moi LL MC Wolf: Gesang Weylas LL MC Beethoven: Fidelio

I don’t know for sure where this Fidelio master class took place, but Shirley Sproule (see below) was the singer. Lehmann’s demonstrations quickly let us know why she was so famous in the role.

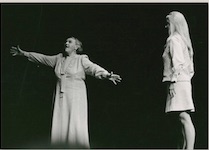

Shirley Sproule is the singer on the right

Lehmann Vignettes by Shirley Sproule

[Sproule was a Lehmann student and later a friend.]

When I went to the Music Academy in the summer of 1953 I had no intention or expectation to sing for Lotte Lehmann. Information received from the Academy stated “a limited number of students will be chosen to participate in the class.”

When I first heard a record of Mme Lehmann I was new to the world of studying singing. Her singing made me numb with awe and wonder…how she could step off a record, be IN the room with the listeners. This beautiful rich voice which gave one so many colors…

I heard her sing three recitals in Montreal and one in Town Hall, NY. After her New York recital I walked with a friend to our hotel, not a word spoken. In my room all I could do was fall onto my bed and weep—a long time. In this way I try to explain why I felt I could never sing for her. My teacher in Montreal wanted me to apply to the Academy to study with her. I decided if I were accepted I would not, of course, be singing, but listen as hard as I could to everything Mme Lehmann would describe about poetry, etc., and I would write as many notes as I could. I would then go back to Saskatchewan where I was teaching and have so much more to offer students.

All my confirmed ideas about not singing for her were shattered as I was paying my fees that first day of school (1953) as Dr. [Frances] Holden was giving me my receipt, and said, “By the way, Mme Lehmann would like to hear you this afternoon.” Yes, I did sing for her, very obviously shaking (but not the voice…). In these vignettes I want to tell of the versatility, the sensitive depths of Lotte and how she changed my life. Words to describe her have always been difficult for me…

1953 was the first year the Academy offered master classes open to the public. There was little knowledge of what auditors, etc, could expect to experience when attending a master class.

It was decided that the faculty would choose “volunteer” students and give mini-master classes, allowing them to perform, and give little suggestions for an improved technique (piano) or communication, as with singers. The Recital Hall [now called Lotte Lehmann Hall] was jam-packed.

Gyorgy Sandor presented a student; Sacha Jacobson had wonderful Irene Rabinowitch; Simon Kovar had, I believe, a clarinet student, Dr. [Richard] Lert, a conducting student who was to conduct the orchestra, accompanying a singer (I was that singer) and Mme Lehmann prepared two singers, Marcella Reale and Joe Meyers. Reale sang Mimi’s first act aria leaning against the piano and arms outstretched from the body along the piano. She was very confident and had just sung performances of Mimi for a production of La bohème with the Pacific Opera Company. She sang beautifully and everyone appreciated her ability. Lehmann commented, “You sing it so well, Marcella, but you present it a little bit as if you are singing at a piano in a cabaret bar.” That set off everyone including Marcella, who bent over laughing, too. I remember thinking “how could this wonderful, serious artist know about cabaret bars?”…I never did ask Mme Lehmann about it.

Next, Joe Meyers who had red hair, very white skin, and a lovely, lyric tenor voice. Joe sang “Heidenröslein” by Schubert. Very securely he sang this delightful song with Mme Lehmann interrupting gently with a few ideas and then asked him to sing the song through, incorporating the little adjustments. Joe did, and Mme Lehmann said, “Joe, you sing quite delightfully, and especially so with your little rosebud mouth.” Well, the hall erupted. The laughter and delight over that small, innocent remark totally charmed everyone, and Joe laughed too.

I had wonderful assignments that summer…Mme Lehmann first gave me the Marschallin in Act III on the day I auditioned; then Mr. [Fritz] Zweig gave me “L’Enfant Prodigue” by Debussy. The next week Mme Lehmann asked me to “look at” the first (big) scene Act I of Der Rosenkavalier…the Marschallin with the words, “It is a lot of work. You are doing Act III and the Debussy but—it would be nice if you could learn the monologue too.” Of course, if she asked me, I’d try! So, I did learn all of the Marschallin except the levée scene, that summer.

There was to be a performance with the orchestra in the Lobero Theater [off campus, downtown Santa Barbara]. The morning of the concert was a dress rehearsal at the Lobero. I wasn’t expecting Mme Lehmann to be there, for she had been at the rehearsal on the night before. But she was. Our student orchestra was so superb and it was a great pleasure to sing with them. Mr. Zweig, of course, was a most gifted, considerate, and outstanding conductor. He was a marvelous musician and coach, and what he helped you learn definitely stayed “learned.” We got through the rehearsal in good order, no interruptions necessary to remedy an errant phrase, etc. Mme Lehmann and Dr. Holden came to us after and Dr. Holden said to me, “Oh, Shirley, you have no idea how good it is.” I had no measuring stick whatsoever, but it pleased me very much that she was happy about it. Then Mme Lehmann came up to me and took my hand and told me how well it went and asked me to watch two little things, saying, “I know it’s a very small detail, but if you can, try: sometimes your and Enid’s [the other female singer] hands are at the same level: just watch it out of the corner of your eye, and if you see that, lower your hands slightly.” The remark was merely a finishing point but what an eye for detail! And such a simple way to correct it. Mme Lehmann had a little trick…when she was moved or very pleased with work in class—of taking a student’s chin in her hand and raising it to look into your eyes. I had seen her do it in class with other students who did very good work and deserved high praise from her. Well, she did it to me and then leaned forward and kissed my cheek. I was floored because I never thought of her doing it to me! Then she smiled, and off she and Dr. Holden went. The next morning, speaking with her on the telephone, she said, “You even remembered the hands….”

During the 1954 Academy season, among other opera scenes, I was assigned Octavian in Act I of Der Rosenkavalier. I had great qualms as to how to walk like a boy and react to the Marschallin. But Mme Lehmann, always generous and patient and so very good at explaining the reasons for ways of responding, made it an unforgettable experience for me.

One “bring-down-the-house” moment I recall was when the Baron has left, Octavian returns in riding habit and Mme Lehmann had indicated that I, as Octavian, was to be close to Marie Theres’, comforting her, but when she sings that “one day he will leave her for someone younger,” I sprang up away from my position on my knees beside her, arms open wide in protest and to emphasize my great love for her I flung my left hand against my chest as in agonizing tones I asked “Why do you torture me and yourself, Theres?” In the stream of my fever and furor Mme Lehmann walked towards me and asked, “Shirley, where is your heart?” “Here, Mme Lehmann.” She started moving more towards me, shaking her head from side to side, saying in warm, strong, convincing tones “No-o-o I don’t think so, Shirley.” I suspect my hand was too high, and it might have looked as if it were possible I could strangle myself, but the whole hall burst into laughter. The next day to my grateful ears, she told me, “You really were a quite good Octavian, Shirley.”

Mme Lehmann was very desirous that the Academy develop and become a year-round school. In the fall of 1954 she held a small class for the Winter on Saturdays in the Recital Hall. It was a truly wonderful time. Natalie Limonick came up to play for us, Marcella [Reale] was in the class and Benita Valente and I. There may have been two or three others as well, but faces and names elude me. [Shirley was in her late 70s, when recalling these Lehmann stories.]

As usual, Mme Lehmann gave us assignments for each week. One Saturday Marcella was to sing “Gretchen am Sprinnrad” by Schubert and was, as usual, very well prepared. Somewhere along in the second page she began to weep. I was full of admiration because she kept on singing and the tears kept flowing. Everyone was weeping with Marcella, especially the most sensitive one, our Lotte Lehmann. Marcella finished, Natalie wound up the postlude with the tears streaming, and in the silence immediately following, the gulps and sobs were quite audible. I remembered I had a large box of Kleenex in the car so asked Benita if she could run out and get it. She was out and back in a flash, offering the Kleenex to all of us. There was a special warmth there as we struggled to regain composure. Then Mme Lehmann spoke: “You know, Marcella, you sing it so well, but when we are singing we are hoping to create images which give the audience the ability to understand the poetry more from their own experiences. If you as a singer get so emotional and the audience responds in the same way it just gets too wet!” [Lehmann advised her students not to cry, but to make the audience cry.]

Mme Lehmann could be very perceptive but did not always spell out a concern, even as impulsive as she could be. In the winter 1954–55 she called me and asked if I would drive her in to the Academy to hear a recital sung by Carl Zytowski. As we stood outside the Recital Hall looking over the program I somehow sensed she was looking at me. I asked, “is there something I can get for you?” Very quietly she said, “I just wonder if you have enough elbows of steel, Shirley,” so pensively. I knew what she meant, so replied, “Well, I guess I’ll just have to see, Mme Lehmann, and if I find out I don’t, I’ll just try and find some.” While I’m persistent, even dogged and dedicated about my application to my learning, I have (had) no enjoyment with aggressive and argumentative dialogue. As she said that, I thought, “Boy, she surely hits the nail on the head!” She certainly diagnosed me very accurately.

Years later in Europe, when I was in an audition situation and had to stand up for myself, I wrote Mme Lehmann of the event and really thought she’d be pleased I had taken some courage to speak out and had found a few “elbows of steel.” When she responded to the story there was not one word of my bravery and I grinned to myself over it. I still do.

Mme Lehmann had such sensitivity to what a person could feel when singing in class. I remember once when someone was singing something I knew and liked very much, I was being carried away with it. Mme Lehmann did not interrupt the singer but there was a poignant silence after the song. Then, very gently and with pain in her voice she said, Oh, ____, You sing so well but I just can’t help you if you cannot open up more.” I’ll never forget how she looked as she said that. It hurt her to not only say that but that she couldn’t remedy the situation.

In the summer of 1955 we experienced an unusual phenomenon: a singer talked back in no uncertain terms to Mme Lehmann. The room froze. She had ripped through the Mozart song at a non-stop, furious pace and boom! She was done. There was a silence before Mme Lehmann spoke and tried to suggest that some adjustment in the tempo might give the singer some advantage to show more clarification of the ideas. Answer? “I like it the way I did it.” Quite slowly and quietly, our teacher spoke. “You have a lovely voice and I believe you understand what the song has to say.” Walking a bit towards the singer… “If sometimes in moments of stress a tempo will move more than anticipated then the ideas of the phrases tumble after each other so quickly the listener cannot separate them clearly enough and the singer’s efforts will not be understood.” And very quietly she moved slightly toward the singer and looked up at her, directly looking into her face and with a little smile said, “Could you please try it again at just a little slower tempo?” Well, one would have had to have been the Sphinx incarnate not to respond and so, reluctantly and somewhat indifferently, the singer said she’d try. It was not a recreation of masterful interpretation but “An ‘A’ for effort” and one could feel the room relax and how we marveled at Mme Lehmann’s patience.

In the Fall of 1954 she assigned me the role of Chrysothemis in Electra by Strauss. Mr. Zweig had worked with me and he always gave such wonderful support. In mid-January Mme Lehmann said we would start staging and Mr. Zweig would come to Santa Barbara and we’d work in the Recital Hall. Benita and I were living in the dear little cottage below the Academy now known as the Treasure House.

Mme Lehmann outlined for me the various directions to cover as I was singing the scene. I had always been comfortable with usage of breathing and I knew Mr. Zweig’s tempi and enjoyed the challenge of this hysterical role. We worked diligently but the constant drive vocally with the intense hysteria found me fighting for breath. Finally, I broke down and cried out, “I can’t give any more sound and fight with this tempo. I know the music, but I can’t seem to ride it,” and burst into tears and tore out of the Recital Hall down the hill to our little cottage. Benita came quickly after me and I was already in the little kitchen, starting to bash pans and washing dishes. I really tore into washing those dishes! I was so upset, so disappointed in myself, feeling I had let down Mr. Zweig after all his work with me, and also fouling up Mme Lehmann’s plans and hopes to present Electra. Benita couldn’t keep up drying the dishes as fast as I pushed them at her and gulping, trying to really stop the tears I heard Benita say, “Oh, oh” and I looked at her without saying anything and she said, “Look.” It turned out Mme Lehmann was coming down the steps to our front door. Oh, how I wondered how on earth I could apologize. Benita said, “Go, Shirl, I’ll finish here,” so I went to the door hoping my face wasn’t too streaked. I just looked as I opened the door and Mme Lehmann spoke so gently and said, “Shirley, we should talk.” It seemed the very open living room might not be private enough so I led her in my bedroom where there were two twin beds. She moved in between the beds and sat down on one and I sat on the other, facing her. I trusted her judgment so much I hoped I could find words for the whole situation. I had never run up against a fiasco quite like this. Her eyes searched mine and very quietly she asked, “Shirley, what can we do about this?” “I think I don’t have the right voice to ride the drive in the music. It think it needs a heavier, larger voice.” Warm silence. “Don’t think I can give more volume unless I push the voice somehow and I’ve never done that. I think I could hurt my voice…It is only fair to you that you use someone who does have a bigger voice, someone else will undoubtedly be more right for Chrysothemis.” There was a little time of silence, but somehow it was a remarkable silence and our dear, so understanding Mme Lehmann said, “I’m so glad you made that decision, Shirley, because if you hadn’t I would have. You do have only one voice and we don’t want anything to happen to it.” How can one not be grateful for such a teacher?

One day, driving her to L.A., no conversation, then suddenly she spoke with such pain in her voice, “Oh, Shirley, I am so worried about _____.” (A student who was romantically involved with a married man.) “My husband left his wife for me and his children never forgave me.” And tears were flowing. I knew nothing about that and what can one say to help comfort? I just held the steering wheel with my left hand and reached over putting my right hand over her clasped hands and we drove quite a few miles that way.

In addition to the four summers I studied with her, I had the joy to work with her in the Winters of 1954–55 and 1955–56. I am a good “sponge” and I was there to absorb as much as I could. One day she telephoned me, I believe in early Spring 1956. “Shirley, you have been working so hard and so long without a break, you need a little holiday. You should drive over and see Monument Valley. It is beautiful and unique. I’ll pay for your trip.” I was totally aghast. Here I was, having this wonderful opportunity to study with her and she wanted to pay me to take a holiday? There was no way I would or could accept that! But such a thoughtful, gracious, special person!

In 1953 Joe Meyers was scheduled to sing “Der Erlkönig” by Schubert. Mme Lehmann had been encouraging us to try to be involved in a song and to communicate. The song progressed through the four first characterizations and Joe stolidly and cleanly sang without one iota of expression. Mme Lehmann was sitting in an armchair and suddenly I saw her hands move to the arms and she was on her feet. “Now Joe, you asked to sing this song, and now you are doing nothing with it, with any of the four characters.” There was more, but I kept hearing, “You asked to sing this Lied.” It would never have occurred to me to ask to sing a certain song. But in 1955 I found a song which appealed to me primarily for the poetry, though the melody was [only] palatable. I decided to ask if I might sing it in class. “Yes, of course, Shirley.” I have here the title of the song; the composer was Robert Heger. I dug in and learned it and took it in to Mrs. [Gwendolyn] Koldofsky who could romp through anything with grace and panache. The accompaniment was rather busy; widely spaced arpeggios and scales and really quite florid. It didn’t particularly match up with the poetry. She looked at me and said, “This is really not your usual type of song, Shirley.” I agreed, but said it had appealed to me. I confessed I’d asked to sing it and felt I shouldn’t back out. Came the class. I sang it with energy and my enjoyment of the text, but the piano was definitely not a compatible partner to the text. After I finished there was generous applause and then silence. Finally Mme Lehmann said, “Shirley, for the life of me I can’t figure out why you wanted to sing that song.” My reply was, “Well, Mme Lehmann, I really liked the poem and wanted to sing it.” She asked, “the poem?” and I said, “Yes, Mme Lehmann, it was one of your poems.” Her eyes flew open and she spoke, “It was??!” in total astonishment! Of course the audience and Shirley doubled up laughing. Her lovely poem had been so poorly used that she had not recognized her own words!

In early 1955 we were driving back from L.A.; I recall she had gone down to hear auditions—students wishing and hoping to come to the Academy. Driving along she was very quiet and with my right hand keeping the rhythm going, I “sotto voce” sang my memorized Chrysotemis. Out of the blue, came from her, “Shirley, I wish you’d call me Lotte.” My right hand stopped every manner of music and I clamped the wheel. I couldn’t believe I heard such a thing. The resulting silence was laced with explanation points and questions! And she said, “I didn’t mean you should stop practicing,” with her touch of apology, which floored me, but I wanted to laugh. How could I simply keep on with practicing when such a request/statement came to me. It took me four months. She never queried why I wasn’t [calling her Lotte]; she just let me work it through. Very near the end of the fourth month we were in discussion about something and I responded, “but Lotte, it could be…” and stopped flat out. She never once said, “Well, it took you a long time,” etc…but that smile was there and I sense she felt I had come to terms with a barrier. I never called her “Lotte” when with other students. If she had extended the privilege to others that was a different matter and their privilege.

The singers who had the joy to study with “Lotte” have, in the deepest sense, the appreciation to nourish the unforgettable times, memories of communication and warmth, and they cherish the imprint and input from this remarkable artist upon our lives.

Memories of working with Lehmann recounted by the late Shirley Sproule.

Benita Valente Remembers Lotte Lehmann

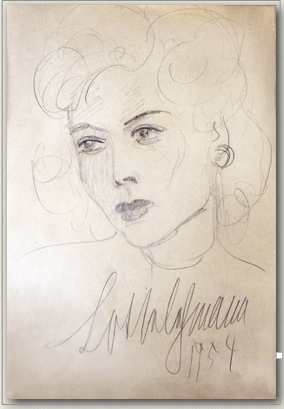

LL’s drawing of Benita Valente

On the long path to becoming a professional singer, I was fortunate to work with a number of exceptional musicians. My high school music teacher in Delano, California, Chester Hayden, was the first among them, and it was he who led me to the legendary German opera and Lieder singer Lotte Lehmann.

Lehmann, who had just retired from the stage and was heading the vocal program at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, accepted me for the nine-week summer session in 1953. Based on what she heard in our voices, she created an individual recital program for each singer whom she took on as a student. This was a special and unique gift, reflecting her largesse, and it proved to be of great value to me as I continued in my studies.

In all, I spent four summers at the Academy. After the second summer, I moved to Santa Barbara and, shortly after that, was accepted at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where I studied with baritone Martial Singher, but continued at the Academy for two more summers.

The schedule there was intense. From Monday through Thursday, we would prepare the repertoire that Lehmann had chosen for us for her master classes, working with soprano Tilly de Garmo on vocal technique and with her husband, conductor/coach Fritz Zweig, at the piano. They were among many gifted musicians who had fled Nazi Germany for the United States, and we were so fortunate to have the opportunity to learn from them.

On Friday and Saturday, Lehmann held two-hour master classes on interpretation, open to a paying audience and held in a large, elegant room of the Spanish-style mansion located on a cliff near the Pacific Ocean. Fridays were devoted to German and French art songs and Saturdays to operatic arias and scenes. The roughly eighteen students sat in the hall observing, and Lehmann (whom we always called “Madame Lehmann”) would call us to the stage individually, or as a group for opera scenes, to perform selections from the repertoire selected for study that week. Occasionally, when she heard a vocal problem, she would refer us to Tilly, and, during one summer, to tenor Armand Tokatyan.

On Friday and Saturday, Lehmann held two-hour master classes on interpretation, open to a paying audience and held in a large, elegant room of the Spanish-style mansion located on a cliff near the Pacific Ocean. Fridays were devoted to German and French art songs and Saturdays to operatic arias and scenes. The roughly eighteen students sat in the hall observing, and Lehmann (whom we always called “Madame Lehmann”) would call us to the stage individually, or as a group for opera scenes, to perform selections from the repertoire selected for study that week. Occasionally, when she heard a vocal problem, she would refer us to Tilly, and, during one summer, to tenor Armand Tokatyan.

The first Lied I sang for Lehmann in 1953 was Schumann’s “Die Lotusblume,” set to a poem by Heine. Because I had not heard German spoken or sung before, it took me two weeks to memorize the song, but there was a lotus pond down the road from the Academy that I used for inspiration. I also sang “Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht” by Brahms, which struck me deeply because my mother had died in 1954. Lehmann must have felt my strong connection with the music, for she was gentle with her critique.

In a professional career of over four decades, Lehmann had shown an amazing gift for taking on virtually any role or song and making it her own. She was always guided by the text, which she considered to be the key to expression and color. As her students, we reaped the benefits of this vast experience. We had to memorize each piece, and if we forgot the text Lehmann, puzzled, would say: “I would rather have forgotten the music than the words.”

Sometimes, when we just couldn’t achieve the results she wanted, Lehmann would step onto the stage to sing an aria or song, often an octave lower, that we were working on. On days when her allergies were not bothering her, she would sing it as written. Watching and listening to her, we were mesmerized by her ability to transform herself magically into another persona and overwhelmed by the depth and range of emotion she expressed. She opened us up to the many possibilities of interpretation and made it clear that she did not want us to copy her, but to develop our own means of expression. By the end of each class, I had experienced such a range of emotions that I found I had developed a splitting headache and had to go back to my room to lie down.

Sometimes, when we just couldn’t achieve the results she wanted, Lehmann would step onto the stage to sing an aria or song, often an octave lower, that we were working on. On days when her allergies were not bothering her, she would sing it as written. Watching and listening to her, we were mesmerized by her ability to transform herself magically into another persona and overwhelmed by the depth and range of emotion she expressed. She opened us up to the many possibilities of interpretation and made it clear that she did not want us to copy her, but to develop our own means of expression. By the end of each class, I had experienced such a range of emotions that I found I had developed a splitting headache and had to go back to my room to lie down.

Lehmann had sparkling blue eyes and wore elegant but simple ankle-length dresses, sometimes with a scarf of the same beautiful material. When each session was over she would sweep out of the room past the audience, surely aware of the impression she had made on us, her spellbound students. Yet she was, at the same time, a warm and friendly presence and took a personal interest in her students, being especially curious about our love life. “Haf you never been in love?” she would ask if we lacked the requisite romantic emotion in a song, and she would rhapsodize about moonlight, innocently translating the German word “Mondschein” into “moonshine.”

Valente teaching

Learning how to act and move on stage was another aspect of our training. We were all somewhat awkward and needed to learn the basics. I remember being taught how to die in operatic fashion by our handsome acting coach, tenor Carl Zytowski, and one day Lehmann said to me in class, “Benita, I have heard that you have learned to die beautifully. Please die for us”—which I did! The acting lessons were valuable for our opera scenes and for the complete operas that were staged once a summer, though my skill in dying was not called for in the roles I was given: Barbarina in Le Nozze di Figaro, the Echo in Ariadne auf Naxos, and Adele in Die Fledermaus.

Another major influence at the Academy was Lehmann’s older brother, Fritz Lehmann, a highly regarded vocal coach who came to all the master classes and worked individually with some of us in his home in Santa Barbara, in the presence of his warm and loving wife, Theresa. Fritz shared my great love of Mozart and recognized that Mozart’s arias and songs were ideally suited to my voice. How right he was! Mozart became the cornerstone of my operatic career, with such roles as Pamina in Die Zauberflöte; Susanna, and later the Countess, in Le Nozze di Figaro, and Ilia in Idomeneo.

In addition to the summers at in Santa Barbara, I spent a winter there as part of a small group of singers working with Lehmann solely on Lieder. In this more intimate setting with students she knew well—at the end of each master class— Lehmann would sweep out of the room in her usual graceful fashion, pass us by and say: “Goodbye children.” Eventually I summoned up the courage to respond: “Goodbye, Mother.” One day there was an outsider in the room and I didn’t want to embarrass anyone, so I said nothing. Lehmann walked by me, looked at me, and, with a twinkle in her eye, silently mouthed the words “Goodbye, Mother.”

Lehmann’s immense curiosity drew her into many areas of life. She enjoyed creating art and did a painting for each song of Schubert’s song cycle, Winterreise. One of those paintings hangs in my studio. She loved gardening and made the tiles for the steps of her garden. She was a frequent letter writer, her handwriting large and sprawling and her words revealing her characteristic truthfulness and emotional openness.

Lehmann had a great love of animals. She owned two myna birds who could be heard from the garden imitating her speaking voice exactly. Once Lehmann asked soprano Shirley Sproule, who was my colleague and voice teacher at that time, to drive her to Los Angeles, and I happily went along, thrilled to be in her company. On our return we passed a schoolyard. Lehmann spotted a crow perched on the monkey bars. Although we assured her that the bird was fine, she later apparently worried that it was caught in the bars and insisted that her friend Frances Holden drive her back to the schoolyard. No bird remained—it was free!

In my current life as a teacher of voice, I think often of Lotte Lehmann, of her larger-than-life personality, her magnetism, her ability to become different people on stage. No wonder such major creators as Richard Strauss, who composed music for her, and Arturo Toscanini, who conducted her in performance, were so entranced by her! For me personally, one of Lehmann’s most important gifts was to open my path to loving the Lied and the song repertoire in general. Her equal commitment to opera and art songs has inspired me to follow the same path, adding chamber music, oratorio, and contemporary works to my own repertoire. I have accepted as key her principle that the words lead the way to the expression and color that the composer intended.

Harold Wright, Valente, Serkin, preparing Shepherd on the Rock

Lotte Lehmann, along with pianist Rudolf Serkin, who was a mentor to me at the Marlboro Music School and Festival in Vermont, and soprano Margaret Harshaw, with whom I studied from 1969 until 1995, two years before her death, were the musical greats who inspired me in my life in music. Passing on their artistic vision to future generations is both my responsibility and my privilege.

[I received the following email message from Ms. Valente in March 2016] …thanks for urging me to write this Preface, for it caused me to bring back to mind so many wonderful memories that I have stored away all these years!

[I discovered the following Lehmann MAW master class from the early 1950s in which Valente sang Schumann’s “Soldatenbraut.”] MC of Soldatenbraut

Natalie Limonick: Lehmann Teaching

[Dr. Sproule mentioned Natalie Limonick in her Vignettes. I had also asked the late Limonick for Lehmann memories, which she graciously sent. Natalie Limonick accompanied singers in master classes held by Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West and was associated with that institution for decades. Former Professor of Music and General Director of Opera at the University of Southern California, Ms. Limonick was also Associate Director of Opera at the University of California at Los Angeles, where I met her. She accompanied such art song specialists as Elly Ameling (when her regular Dutch pianist was unavailable), Carol Neblett, and Marni Nixon. Active in the musical life of Los Angeles almost until her death in 2007, she had long held the position of President of the Opera Guild of Southern California. Here are her memories.]

Before ever having met the great lady, I first heard her recordings in the opera and Lieder classes that I took with Dr. Jan Popper back in 1953–55 at UCLA. I fell completely in love with her total artistry, text involvement, beautiful vocal timbre and evenness of quality throughout her range. The emotional content was stirring and so deeply committed that one became a devotee for life.

There followed a weekly drive from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara for the two-hour Saturday afternoon opera master classes to observe Mme Lehmann in the role of mentor to the young hopefuls. And since I was a neophyte in the repertoire, I just learned by observation, osmosis and inspiration. Lehmann’s world became an extension of the exciting art of music.

After greeting the class (and audience) Lehmann would offer a deeply felt translation of the text (all parts), discuss the situation at the specific moment of the scene, and give a marvelously insightful characterization of each of the roles. Then the students performed. Some of the students were better equipped than others, but essentially they were more advanced singers, such as Grace Bumbry. By the way, in 1960 Grace was the “schwarze Venus” in Wieland Wagner’s Tannhäuser and I was there coincidentally as a scholarship winner to Friedelind Wagner’s “Meisterklasse” in Bayreuth.

Another of those master class participants at the Music Academy was Lotfi Mansouri. He and I were fellow students in Dr. Popper’s opera history classes followed by the opera workshop. Lotfi also took part in Mme Lehmann’s Lieder classes. I remember his performance of “Ich grolle nicht.” He was one of the few who was able to absorb her suggestions, but then do his own thing.

I don’t recall Lehmann ever talking technically to students. Her passionate concern was interpretation, dramatic presentation, total involvement with communication. Armand Tokatyan was the voice faculty artist at the Music Academy who helped with vocal technique.

My special opera class favorites were the scenes between Eva and Hans Sachs in Meistersinger and the Rosenkavalier “Presentation of the Rose” and last act final trio. After the student performance, Mme Lehmann would walk to the small stage and proceed to demonstrate each character (men included). I fell in love with her as Hans Sachs….so warm, loving and understanding of Eva’s emotions. “He” communicated his feeling of protectiveness to me in the audience; it was stirring. Also, her awareness of the aesthetics of line, whether visual or aural—totally in sync with the whole picture. The way she held the rose as Octavian presented it to Sophie—elegance, line, the feeling Octavian was sensing as he extended it to the lovely, innocent young girl. I have carried that picture with me constantly.

No matter what repertoire—Pélleas, Manon, Marriage of Figaro, Freischütz—all were given the same depth of expressiveness and credibility. It was magic.

It wasn’t long before I alternated [as pianist] with the Friday afternoon art song master classes and the Saturday opera classes. A whole new world opened up. The same approach—translating in fluent (though accented) English the poetic texts. One hardly needed the song, so lyrical was her reading. Then the student would sing. Lehmann would often rise from her throne-backed chair and offer suggestions. At this point in her life (retired from the stage) she would say, “I will demonstrate, I do not sing anymore, but if I do, it will be an octave lower.” And, “Don’t copy me, but let your imagination pick up cues from what I do, then do your own interpretation—but please feel it, mean it.” “No, no,” she would say, “you sing like soldiers on guard duty—sentries posted at different places—connect them—legato.” For some, her personality was so strong that they could only try to imitate. Others would come through with inspiring changes, freed from emotional restrictions.

One memory while auditing the Lieder classes concerned Hugo Wolf’s “Verborgenheit.” The words tell of retreating from the world… “Let me be, O world…leave this heart to know its own bliss, its own pain.” A young student sang it and when she was through Lehmann said that she’d demonstrate. “This song could be the story of my life,” she said as she looked out through the French windows with summer sun glinting onto her brilliant blue eyes, “I too have known the adulation of the world and now seek only my private joys.” She then, still facing out to the garden, began to sing, but not in the breathy baritone we’d come to expect, but in the correct range and key…glorious in sound and emotional meaning. The pianist, Gerhard Albersheim, joined and, as if lost in another world, Lehmann sang through this deeply introspective song. When she finished, there wasn’t a dry eye in the room, but when Lehmann, now brought back to reality, tried to quiet the applause, one knew that she was both deeply involved in the song, and completely aware of her audience. She then turned to the young student and said, “Now my dear, will you try it again….”

After some time I became Dr. Popper’s assistant and then came the supreme opportunity when he brought me to the Academy for the full summer session to assist him in the preparation and coaching for the master classes which he was accompanying. Lotfi was the stage director and I the music director…a long and unique relationship.

I played for the opera classes and during my first year working there, helped prepare Ariadne auf Naxos in a complete performance with Abravanel conducting the orchestra. The cast included many fine voices, some singers such as Marni Nixon, Benita Valente, and Norman Mittleman, who went on to important careers. Lehmann presented one of her artistic creations to each staff member. I still have the watercolor poster she gave me of two of the characters in the opera.

I did not play for the Lieder classes (Gwen Koldofsky was the pianist for those), but some years later I did play for students who had private lessons with Lehmann at her wonderful home in Hope Ranch.

The only negative memories I have from that time were Mme Lehmann’s attempts to govern students’ personal lives, which seemed uncalled for. She would say things like “Don’t marry.” “Don’t have children.” etc. Also, she was not able to conceal which singers were her pets, but…in light of all she offered, these are minor infractions of behavior which fade from the picture. She was a powerful personality. Young people are impressionable and tend towards idol worship. But all the good overshadows any of the negatives. After all, idols are human beings and it’s only natural for them to have feet of clay, which tend to become exposed over time.

Lehmann London Master Class Impressions

[These impressions were taken from the book Wigmore Hall 1901–2001 A Celebration][There have been special concerts to celebrate the centennial of this fine, intimate concert hall, and now this wonderful book. There are many memories about the famous artists who have performed in Wigmore. Lehmann didn’t sing there, but she taught master classes there and that is what is remembered. William Lyne, Manager of the Wigmore, recalls his initial days there as Assistant Manager.]

My introduction to Lieder had been through the recordings of Lotte Lehmann and Elisabeth Schumann. Lotte Lehmann was still alive but had long stopped singing. Nevertheless, I had always hoped that she would return to Australia [his home], which she had toured in the past, maybe for master classes; then I would at least see and hear her. The very first performances I managed in my new post at the Wigmore were Lotte Lehmann master classes! At these classes, there were twelve in all, Lotte Lehmann intoned the songs and arias she was teaching; tenor, soprano, bass, mezzo, it did not matter, in fact I suspected that she relished the opportunity to perform arias such as Don José’s “Flower Song” from Carmen. At one lesson on her most famous role, the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, she broke into full voice, and the whole audience burst into applause. Lotte Lehmann returned two years later; this second set of classes introduced both Janet Baker and Grace Bumbry; the latter gave a recital when the classes had finished. I know that Dame Janet was not very happy about the classes, but I recall that she contributed a memorable and moving performance of Schumann’s Frauenliebe und -leben. [Janet Baker wrote to the author upon receiving the World of Song award from the Lotte Lehmann Foundation. She revered Lehmann and said that an agent was in the Wigmore Hall when she sang, and engaged her. It was the beginning of her splendid career.]

[Jacqueline Faith, one of the Friends of Wigmore Hall, wrote as follows.]

In 1959–60 during the unrepeatable series of Lotte Lehmann’s master classes, I still vividly remember a moment of absolute silence following Madame Lehmann’s brief demonstration to the three young singers on stage of the phrase from the final Trio of Der Rosenkavalier—“ich weiss’ auch nichts, gar nichts.” I had never before heard that work, although many of the audience had, but we were all part of the deeply felt silent moment of sheer emotion which greeted her short utterance—an inaudible lump in all throats and a missed beat of many hearts, including mine, based on I knew not what. Unforgettable and still indescribable forty plus years on, and surely woven into the fabric of the Wigmore for all time.

Some of Lehmann’s Students

Lois Alba

Josephine Allen

Judith Allen

Jeannine Altmeyer

Karan Armstrong

Tami Asakura

Rose Bampton

Noelle Barker

Helen Barlow (Harrison)

Judith Beckmann

Peter Bedford

Kathryn Blum Barone

Patricia Beems

Jane Birkhead

John Baird

Anne Bollinger

Helen Bolton

Anne Brown

Grace Bumbry

Christabel Burton (Bielenberg)

Larry Case

Olga Chronis

Lincoln Clark

Enid Clement

William Cochran

Jean Cook

Coleman Cooper

Dr. Sister Marietta Coyle

Robin Craver

Grace de la Cruz

Gretchen d’Armand

Martha Martin Deatherage

Archie Drake

Ruth Drucker

Elizabeth Erro (Hvølboll)

Joseph S. Eubanks

Jeanne Evans

Earl Fisher

Oma Galloway

Edna Garabedian

Janice Gibson

Charles Glass

Victor Godfrey

Olen R. Gowens

Kay Griffel (Sellheim)

Leslie Guinn

Jane Guthrie

Helen Barlow Harrison

Kathryn Harvey

Elizabeth Hawes

Marvin Hayes

Joan Heels

Ronald Holgate

Marilyn Horne

Enid Jacobson

Patricia Jennings (Armstrong)

Emma Jost

Ava June

Beverly Ka’ana

Julia Kemp (Rothfuss)

Joy Kim (Slote)

Ruth Landis

Alice Lee

Martha Leiter

Diane Leoncavallo

Martha Holmes Longmire

William Longmire

Arnold Leverance

John Limpus

Susan Nalbach Lutz

Jeanette MacDonald

Rev. Patrick Maloney

Lotfi Mansouri

Dorothy Maynor

Leila McCormack

Kay McCracken (Duke) (Ingalls)

Adair McGowan

Margery McKay

Raymond Manton

Brunetta Mazzolini (Graham)

Nan Merriman

Joseph K. Meyers

Richard Milius

Douglas Miller

Mildred Miller

Kevin Mills

Ronald Mitchell

Norman Mittelmann

Allan Monk

Ron Murdock

Sally Murphy

Eleanor Murtaugh

Bonney Murray

Timothy Mussard

Rosalind Nadell

Roy Neal

Carol Neblett

Nitza Niemann

Alice Marie Nelson

Maralin Niska

Katsuumi Niwa

Evangeline Noël

William Olvis

Rose Palmai-Tenser

Sue Patchell

John Pflieger

Mary Beth Piel

Naka Pillman

Beata Popper

Harve Presnell

Marcella Reale

Brenda Roberts

Guy Rothfuss

Martile Rowland

Sylvia Rolands

Chieko Sakata

Roy Samuelsen

Dorothy Sandlin

Hazel Schmid

Conrad Schultz

Kenneth Shelton

Myron Slater

Gretchen Smith

Shirley Sproule

James Standard

Eleanor Steber

William Swan

Page Swift

Daniel Taft

Luba Tcheresky

Riki Turofsky

Delcina Stevenson

Mary Lou Sullivan-Delcroix

Benita Valente

Henrietta Valor

Jeannine Wagner

Joan Watson

Lenno Wells

Shirley Westwood

Elizabeth Winkie

Linda Williams (Eddy)

Seoung Lee Wilson

Joan Winden

Kenneth Wohn

Rae Woodland

Roland Wyatt

Shige Yano-Matsuura

Maria Zahlten-Hall

A few singers have sometimes been listed as Lehmann students in error. Shirley Verrett, Mattiwilda Dobbs, and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf never studied with Lehmann.