These Lehmann student obituaries are offered in alphabetical order.

Lois Alba Passes

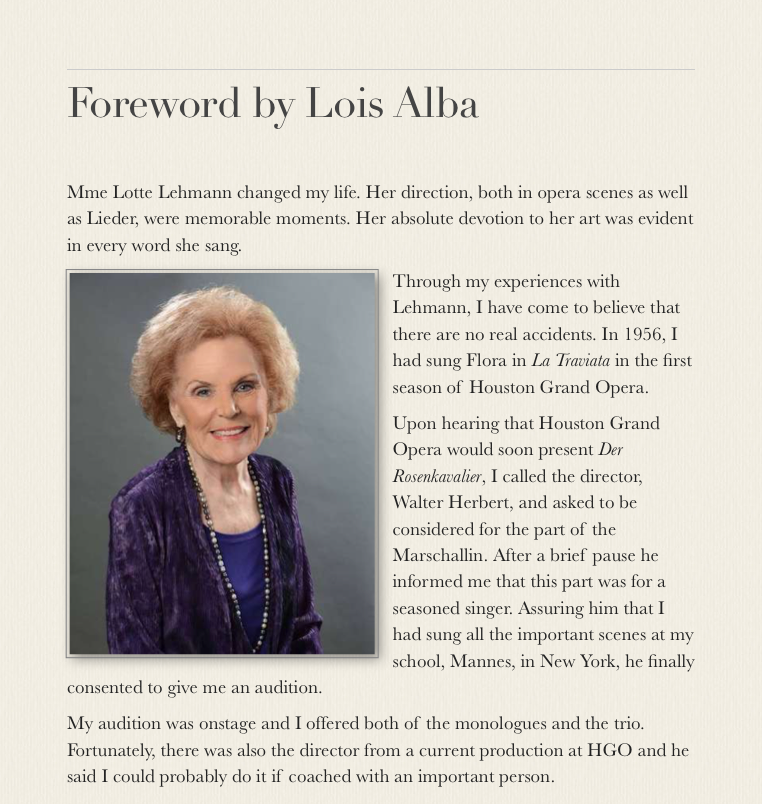

Lois Alba Plummer Townsend Wachter (1928-2025) fell in love with opera at an early age and began taking singing lessons when it became apparent that she had a natural talent and drive.

She graduated from Kinkaid School in Houston at the age of 16 and moved to New York City (with a chaperone) to study music, acting and voice at Mannes as well as the Daykarhanova School for the Stage founded by bormer members of Stanislavsky School of Acting in Russia.

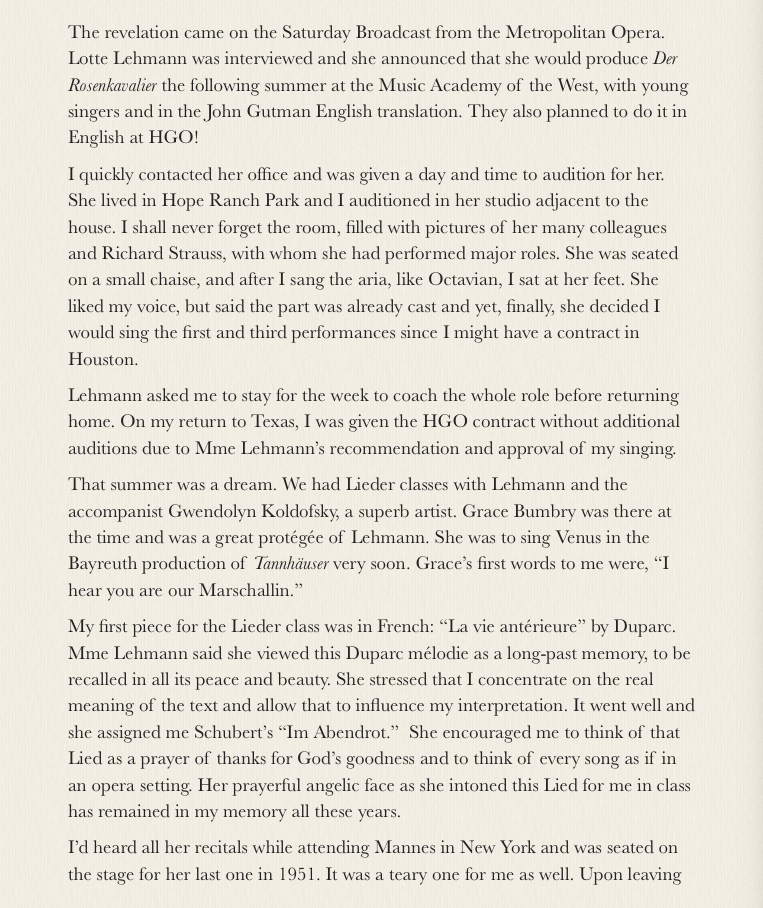

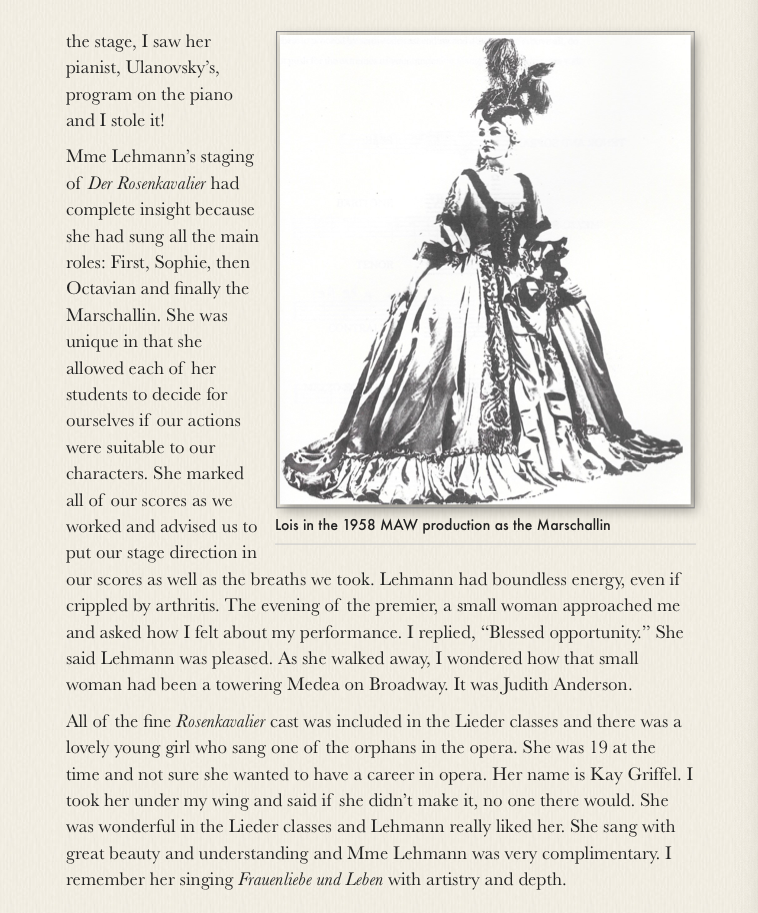

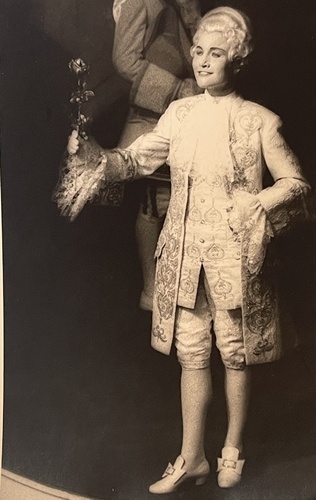

She became the first winner of the Southwest Division of the Metropolitan Opera Competition. Later she prepared the role of the Marschallin in Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier with Lotte Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West where she sang in their production. There she studied other roles and Lieder with Lehmann.

She subsequently sang the role at Houston Grand Opera. She proceeded to perform in recitals and concerts. She met Texas real estate developer, Herbert Townsend. They married and had three children. Her colleagues, including Lehmann, recommended that Lois move to Europe to further her career, which she did and lived in Paris and Milan for 11 years.

A student of bel canto, Lois furhtered her studies with a number of famous singers such as Rosa Ponselle. She appeared in opera in Europe for eleven years performing in the company of many acclaimed singers including Mirella Freni, Mady Mesplé, and Luciano Pavarotti. She performed leading roles in La Traviata, Cosi fan tutti, Turandot, La boheme, Le nozze di Figaro, Otello, Die Zauberflöte and Mefistofle.

Her marriage to Herbert ended amicably. She returning to NYC to live, where she met Arthur Wachter whom she married. Together they founded Soma International Foundation to help young singers advance their careers. They ultimately returned to Houston to be closer to family, and with the help of fellow artist Bettye Gardner and tenor Johnny Jennings, they founded Opera in the Heights and produced many operas there.

In 2016, Lois developed The Lois Alba Aria Competition that enjoyed a 14 year run. They sponsored fundraising events and concerts to earn prize money to help singers further their careers. She maintained a full studio of singers as well.

Her legacy of teaching spaned over 50 years. Lois published Vocal Rescue: Rediscover the Beauty, Power and Freedom in Your Singing.

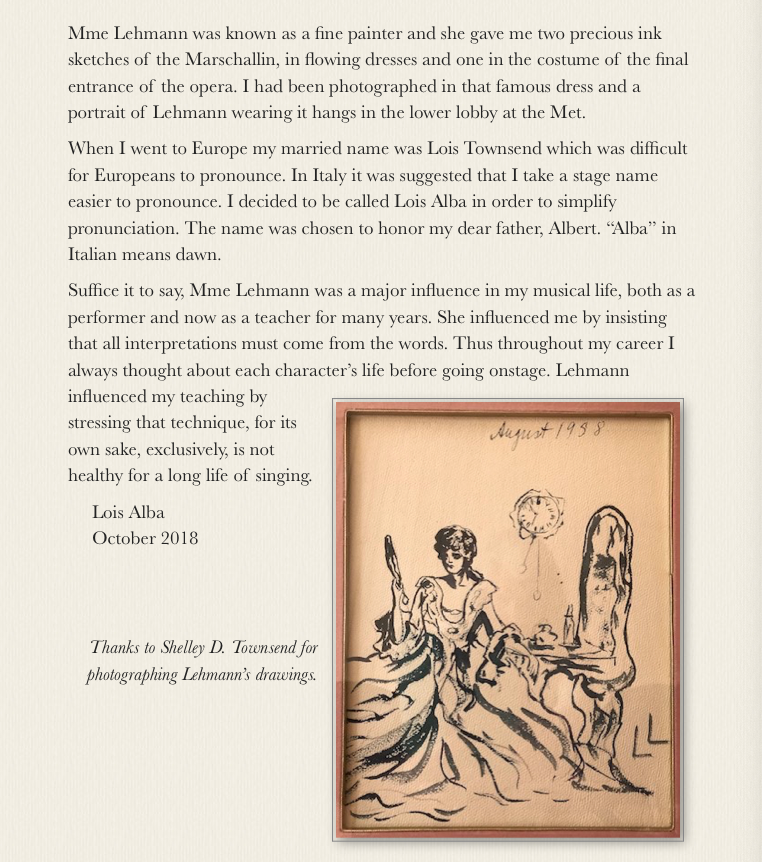

Following is the Foreward she wrote for Gary Hickling’s iBook Volume 6 in the series Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy.

Karan Armstrong Passes

Lotte Lehmann student Karan Armstrong, born in 1941, passed away on 28 September 2021. Born in Havre, Montana, she first studied at Concordia College, later studying with Mme Lehmann. She made her debut in 1965 in San Francisco as Musetta. In 1966 she won the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions and soon appeared in smaller roles at the Met. She sang major roles at the New York City Opera until 1974 when she first appeared in Europe, including at La Fenice, Bayreuth, and Deutsche Oper Berlin, where for almost four decades she sang in over 400 evenings in 24 different roles. You can hear her sing with the Gewandhaus Orchester Leipzig in 1988 with Kurt Mazur conducting “Träume” from Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder.

Judith Beckmann Passes

On February 19, 2022, Lehmann student and soprano Judith Beckmann died at the age of 86.

The American-German soprano was born on May 10, 1935 in Jamestown, North Dakota into a musical family. She received her musical education at the University of Southern California and the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, studying under her father and Lotte Lehmann.

In 1961, she won a singing contest in San Francisco and was awarded a scholarship to study with Henny Wolff at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg and with Franziska Martienssen-Lohmann in Düsseldorf.

In 1962, she made her debut at the National Theater of Braunschweig, in the role of Fiordiligi in Mozart’s Così fan tutte. That debut led her to the Deutsche Oper Berlin and the Bavarian State Opera in Munich. In 1964 Beckmann became a member at the Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf. In 1966 she made her debut at the Hamburg State Opera and in 1967 became a member of the company where she would become one of the most revered singers of her time. With the company, she sang 381 performances in 27 roles and in 1975 she was appointed a Hamburg Kammersängerin. Her final performance with the company came in 1989.

She appeared with the Vienna State Opera in 1969 and in 1986 portrayed the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier. This was not her first appearance in that role, for which, after years away from the Music Academy of the West, she returned to Santa Barbara for coaching with Mme Lehmann. In 1988 she appeared as Ariadne in Ariadne auf Naxos at the Theater Dortmund.

Following her performance career she taught.

Her husband, Irving Beckmann, was a pianist and conductor, who predeceased her.

She is survived by her daughter, conductor, Catherine Rückwardt.

Grace Bumbry Passes

Grace Bumbry, Barrier-Shattering Opera Diva, Is Dead at 86

• Grace Bumbry Zoom guest about LL for Wagner Society

A flamboyant mezzo-soprano (who could also sing meaty soprano roles), she overcame racial prejudice to become one of opera’s first, and biggest, Black stars.

May 8, 2023

Grace Bumbry, a barrier-shattering mezzo-soprano whose vast vocal range and transcendent stage presence made her a towering figure in opera and one of its first, and biggest, Black stars, died on Sunday in Vienna. She was 86.

Her death, following a stroke in October, was confirmed in a statement by the Metropolitan Opera in New York, where she was long a mainstay, performing more than 200 times over two decades.

Growing up in St. Louis in an era of segregation, Ms. Bumbry came of age at a time when African American singers were a rare sight on the opera stage, despite breakthroughs by luminaries like Leontyne Price and Marian Anderson.

But with a fierce drive and an outsize charisma, Ms. Bumbry broke out internationally in 1960, at 23, when she sang Amneris in Verdi’s “Aida” at the Paris Opera.

The following year, she landed in something of a national scandal in West Germany when Wieland Wagner, a grandson of Richard Wagner, cast her as Venus, the Roman goddess of love, in a modernized version of Wagner’s “Tannhäuser” at the storied Bayreuth Festival.

She was the first Black woman to perform at the festival, cast as a character typically portrayed as a Nordic ideal in an opera written by a composer known for his antisemitism and German nationalism. The festival — and newspapers — were flooded with letters asserting that the composer would “turn in his grave.”

Ms. Bumbry was undeterred. Indeed, she was well prepared.

“Everything that I had learned from my childhood was now being tested,” she recalled in an interview with St. Louis Magazine in 2021. “Because I remember being discriminated against in the United States, so why should it be any different in Germany?”

The audience did not share such misgivings: Ms. Bumbry was showered with 30 minutes of applause. German critics were equally enchanted, christening her “the Black Venus.” The Cologne-area newspaper Kölnische Rundschau credited her with an “artistic triumph,” and Die Welt called her a “big discovery.”

Her landmark performance helped earn her a $250,000 contract (the equivalent of more than $2.5 million now) with the impresario Sol Hurok.

It also won her another honor: a performance at the White House, in February 1962. On the advice of European friends who had seen Ms. Bumbry at Bayreuth, Jacqueline Kennedy, the first lady, invited her to sing at a state dinner attended by President John F. Kennedy and Mrs. Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Chief Justice Earl Warren and other Washington power brokers.

Suddenly, she was a star.

“If there is a more exciting new voice than Grace Bumbry’s skyrocketing over the horizon I have not heard it,” Claudia Cassidy wrote in The Chicago Tribune in a review of a recording of her arias the same year. “This is a glorious voice, by grace of the gods given its chance to be heard in its fullest beauty.”

Of her Carnegie Hall debut in November 1962, Alan Rich of The New York Times gave a qualified review, but allowed that “Miss Bumbry has a gorgeous, clear, ringing voice and a great deal of control over it.”

“She can swoop without the slightest effort from a brilliant high to a beautiful resonant chest tone,” he wrote.

Ms. Bumbry transcended not only racial perceptions but vocal categorizations as well. Originally a mezzo-soprano, she made a striking departure by taking on soprano parts, too, which gave her access to marquee roles in operas such as Richard Strauss’s “Salome” and Puccini’s “Tosca.”

“She gloried in the fact that she was able to perform both roles in Verdi’s ‘Aïda,’” Fred Plotkin wrote in a 2013 appreciation for the website for the New York public radio station WQXR. “She could be Tosca and Salome, but also Carmen and Eboli.”

Ms. Bumbry displayed a broad range in her choice of roles. In 1985, she received raves for her performance as Bess in the Metropolitan Opera’s 50th anniversary performance of George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess,” despite her conflicted feelings about a folk opera set among the tenements of Charleston, S.C., and rife with unflattering Black stereotypes.

“I thought it beneath me,” she said in an interview with Life magazine. “I felt I had worked far too hard, that we had come far too far to have to retrogress to 1935. My way of dealing with it was to see that it was really a piece of Americana, of American history, whether we liked it or not. Whether I sing it or not, it was still going to be there.”

Grace Melzia Bumbry was born on Jan. 4, 1937, in St. Louis, the youngest of three children of Benjamin Bumbry, a railroad freight handler, and Melzia Bumbry, a schoolteacher.

A musical prodigy as a youth, she honed her skills in the choir at St. Louis Union Memorial Church and by performing Chopin on the piano at ladies’ tea parties. At 16, she saw a performance by Ms. Anderson, who would become a mentor, and was inspired to enter a singing contest on a local radio station. She took top prize, which included a $1,000 war bond and a scholarship to the St. Louis Institute of Music. She was nonetheless denied admission because of her race.

“The reality was wounding,” Ms. Bumbry said in an interview with The Boston Globe. “But when it happened, I also thought, I’m the winner. Nothing can change that. My talent is superior.”

Embarrassed, the radio contest organizers arranged for her to appear on “Talent Scouts,” a national radio and television program hosted by Arthur Godfrey. After hearing her heart-rending performance of “O Don Fatale,” from Verdi’s “Don Carlo,” the avuncular Mr. Godfrey informed the audience, “Her name will be one of the most famous names in music one day.”

The exposure helped put her on a path to Boston University, and later, Northwestern University, where she fell under the tutelage of the German opera luminary Lotte Lehmann, who became another valuable mentor as Ms. Bumbry moved toward her debut in Paris.

As her star continued to rise over the years, Ms. Bumbry was never afraid to inhabit the prima donna role offstage as well as on, outfitting herself in Yves Saint Laurent and Oscar de la Renta and tooling around in a Lamborghini.

After marrying the tenor Erwin Jaeckel in 1963, she settled in a villa in Lugano, Switzerland. The couple divorced in 1972. Ms. Bumbry left no immediate survivors.

Beyond her prodigious vocal skills, Ms. Bumbry brought a famous sultriness to her roles, a reputation she put to good use for a 1970 performance of “Salome” at the Royal Opera House in London.

She leaked word to the press that for the racy “Dance of the Seven Veils,” she would strip off all seven veils, down to her “jewels and perfume,” as she put it — although the jewels, it turned out, were sufficient enough to serve as a “modest bikini,” as The New York Times noted.

It hardly mattered. “In the history of Covent Garden,” Ms. Bumbry said in a 1985 interview with People magazine, “they never sold so many binoculars.”

• NEW YORK (AP) — Grace Bumbry, a pioneering mezzo-soprano who became the first Black singer to perform at Germany’s Bayreuth Festival during a career of more than three decades on the world’s top stages, has died. She was 86.

Bumbry died Sunday at Evangelisches Krankenhaus, a hospital in Vienna, according to her publicist, David Lee Brewer.

She had a stroke on Oct. 20 while on a flight from Vienna to New York to attend her induction into Opera America’s Opera Hall of Fame. She was stricken with the plane 15 minutes from landing, was treated at NYC Health + Hospitals/Queens and returned to Vienna on Dec. 8. She had been in and out of facilities since, Brewer said Monday.

Bumbry was born Jan. 4, 1937, in St. Louis. Her father, Benjamin, was a railroad porter and her mother, the former Melzia Walker, a school teacher.

She sang in the choir at Ville’s Sumner High School and won a talent contest sponsored by radio station KMOX that included a scholarship to the St. Louis Institute of Music, but she was denied admission because she was Black. She sang on CBS’s “Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts,” then attended Boston University College of Fine Arts. and Northwestern, where she met soprano Lotte Lehmann, who became her teacher at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, California, and a mentor.

Bumbry, known mostly as a mezzo but who also performed some soprano roles. was inspired when her mother took her to a recital of Marian Anderson, the American contralto who in 1955 became the first Black singer at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Bumbry became part of a generation of acclaimed Black opera singers that included Leontyne Price, Shirley Verrett, George Shirley, Reri Grist and Martina Arroyo.

Bumbry was among the winners of the 1958 Met National Council Auditions. She had a recital debut in Paris that same year and made her Paris Opéra debut in 1960 as Amneris in “Aida.”

The following year, she was cast by Wieland Wagner, a grandson of the composer, to sing Venus in a new production of “Tannhäuser” at the Richard Wagner Festival in Bayreuth. Bumbry’s casting in a staging that included stars Wolfang Windgassen, Victoria de los Angeles and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau resulted in 200 protest letters to the festival.

“I remember being discriminated against in the United States, so why should it be any different in Germany?” Bumbry told St. Louis Magazine in 2021. “I knew that I had to get up there and show them what I’m about. When we were in high school, our teachers — and my parents, of course — taught us that you are no different than anybody else. You are not better than anybody, and you are not lesser than anybody. You have to do your best all the time.”

Reviews of her Bayreuth debut on July 23, 1961, were mostly positive.

“A voice of very large size, though a little lacking in color. It is a voice that has not as yet `set,? as the teachers say,” Harold C. Schonberg wrote in The New York Times. “She is obviously a singer with a big career ahead of her.”

As a result of the attention, Bumbry was invited by first lady Jacqueline Kennedy to sing at a White House state dinner the following February. Debuts followed at Carnegie Hall in November 1962, London’s Royal Opera in 1963 and Milan’s Teatro alla Scala in 1964.

She appeared at the Met on Oct. 7, 1965, as Princess Eboli in Verdi’s “Don Carlo,” the first of 216 performances with the company.

“Her assurance, self-possession, and character projection are the kind from which a substantial career can be made,” Irving Kolodin wrote in the Saturday Review.

Bumbry’s final full opera at the Met was at Amneris in Verdi’s “Aida” on Nov. 3, 1986, though she did return a decade later for the James Levine 25th anniversary gala to sing “Mon cœur s’ouvre à ta voix (Softly awakes my heart)” from Saint-Saëns’ “Samson et Dalila.”

Met general manager Peter Gelb said “opera will be forever in her debt for the pioneering role she played as one of the first great African American stars. “

“Grace Bumbry was the first opera star I ever heard in person in 1967 when she was singing the role of Carmen at the Met and I was a 13-year-old sitting with my parents in Rudolf Bing’s box,” Gelb said. “Hearing and seeing her giving a tour-de-force performance made a big impression on my teenage soul and was an early influence on my decision to pursue a career in the arts, just as she influenced generations of younger singers of all ethnicities to follow in her formidable footsteps.”

In 1989, she sang in the first fully staged performance on a work at Paris’ Bastille Opéra in Berlioz’s “Les Troyens (The Trojans).” In 2009, she was celebrated at the Kennedy Center Honors.

Bumbry’s 1963 marriage to Polish tenor Erwin Jaeckel ended in divorce in 1972. Bumbry was predeceased by brothers Charles and Benjamin.

Brewer said memorials are being planned for Vienna and New York.

Lincoln Clark Passes

Stage director and tenor Lincoln Clark, a mainstay of Seattle Opera for a decade (1974-84), died Friday, April? 22, 2016 at his home in Edmonds after a long battle with cancer. He was 90.

Mr. Clark was born in Fort Cobb, Okla., on Jan. 6, 1926. He began his opera career as a voice student in 1946, after serving in the U.S. Navy. He took a job as assistant to Glynn Ross — then director of the L.A. Conservatory Opera, and later the founder and general director of Seattle Opera — and after singing in “La Boheme,” Mr. Clark came to the attention of the renowned singer/teacher Lotte Lehmann. For three years, he studied with her and others at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, which he later called “a life-changing experience.”

Mr. Clark subsequently won a Fulbright grant to study at the Royal Bavarian Music Academy in Munich, which led to 20 years of engagements as a leading tenor in European opera houses.

In 1974, he returned to the U.S. to become resident stage director of Seattle Opera under Ross, working first as assistant to the noted director George London in staging the company’s very first Wagnerian “Ring.” After the first year, London departed and Mr. Clark was left in charge of the then-annual “Ring” for a decade. During that period, he staged the majority of Seattle Opera’s productions, in addition to the summer “Ring” in both German and English cycles.

After his Seattle years, Mr. Clark moved to Florida State Opera at Florida State University, where he remained for 12 years, during which he initiated the doctoral degree in opera performance and the master’s degree in opera stage direction, as well as inaugurating a study and performance program for American singers at the FSU Study Center in Florence, Italy.

From 1997 until 2014, he presented opera-appreciation classes focused on 19th-century Italian opera for Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival in Tuscany, near Siena. After returning to Seattle in 2011, he was invited to lecture for the University of Washington’s Osher Life Long Learning program

In 1996, Mr. Clark returned to freelance directing and consulting. He directed productions and held residencies in Portland and Krakow, Poland, as well as the University of Illinois and Ohio University.

Mr. Clark is survived by his wife, mezzo-soprano Patricia Pease.

William Cochran Passes

William Cochran, one of Lehmann’s students, passed away on 16 January 2022. Born in Columbus, Ohio, Cochran studied at the Curtis Institute of Music with Marital Singher and at the Music Academy of the West, with Lehmann. A winner of the Lauritz Melchior Heldentenor Foundation Award, he made his debut at the Met in 1968, in 1969 with San Francisco, and Covent Garden in 1974. He was a member of the Oper Frankfurt for years, and appeared at the Bavarian State Opera multiple times. Other companies include Hamburg, Vienna, etc. You can hear him singing in his ”Fach” (as Heldentenor) in this live recording from Act I of Die Walküre with Eileen Farrell, soprano.

Archie Drake Passes

Drake, known throughout the Pacific Northwest as Archie, made his debut with the company in 1968. He sang 109 roles in more than 1,000 performances over 39 seasons.

Last season during an 80th-birthday celebration for the singer, Seattle Opera general director Speight Jenkins called Drake the “soul of Seattle Opera—with the amazing longevity of his voice and his enormous stage presence, the variety of his accomplishments cannot be equaled by anyone else in his voice category.”

Drake’s mainstage roles with Seattle Opera included Candy in the 1970 world premiere of Carlisle Floyd’s Of Mice and Men, Wotan in Wagner’s and three roles in Prokofiev’s War and Peace. He recently sang in Boris Godunov, Tosca, Fidelio, and Madama Butterfly.

A descendant of a brother of Sir Francis Drake, Archie was born in 1925 in Norfolk, England, and became a sailor at 15. He served as a deckhand in the merchant navy during World War II.

While working onshore in Vancouver in the 1950s, Drake joined a local choir and was recommended to Lotte Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West. She encouraged him to audition and he made his San Francisco Opera debut in 1968 as Rambaldo in Puccini’s Rondine. That same year he was asked to appear in the Seattle Opera’s 1968 production of Fidelio; he was offered a contract as a permanent member of the company the next year.

Drake died of a massive coronary, according to Seattle Opera.

You may also see Archie Drake in a masterclass with Lotte Lehmann filmed in 1961 and available from VAI Music.

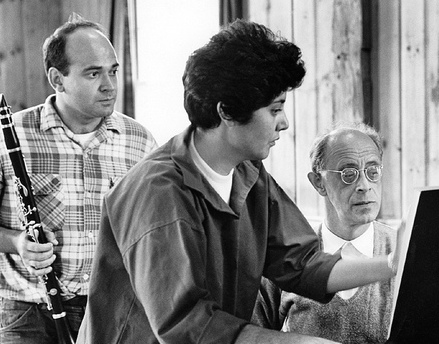

Leslie Guinn Passes

Leslie Guinn was born in Conroe, Texas on April 29, 1935 and died December 12, 2020. His father, Leslie Guinn, was a painter, and his mother, Sybil Guinn, was a homemaker. They recognized their son’s love of music from a very early age.

He attended Northwestern University and with Lotte Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West. You can see him with other Lehmann students in the photo that accompanies the obituary of Luba Tcheresky. Shortly after his graduation, he was drafted and served as a soloist with the US Army Chorus. His New York debut was with Leopold Stokowski singing Carmina Burana, a work he was to sing so many times that he later said it supported his growing family in the early days of his career. He performed with many major symphony orchestras, including the Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Baltimore, National, Cincinnati, and L’Orchestre de Monte Carlo. Early in his career, he performed with such groups as the Abbey Singers, New York Pro Musica, and Music from Marlboro. Summer festival appearances included Marlboro, Tanglewood, Grant Park, Meadowbrook, Caramoor, Saratoga, Casals, Cabrillo, and Aspen Music Festival where he served as Artist/Teacher for seventeen years.

He made his European debut in 1983 singing the title role in a new production of Berg’s Wozzeck with Dennis Russell Davies. As an advocate of contemporary music he premiered many new works including the West Coast premiere of Bernstein’s Mass and William Bolcom’s Songs of Innocence and Experience and several works written expressly for him, including the Rochberg String Quartet #7 and Christopher Rouse’s Mitternachtlieder. His recording of Barber’s Dover Beach with the Concord String Quartet won a Grammy nomination for best chamber music and was included in High Fidelity’s list of “Best American Music on Record.” He recorded Robert Schumann duets with mezzo-soprano Jan DeGaetani and Gil Kalish, pianist. Their recording of Songs of Stephen Foster was named “Record of the Year” by Stereo Review Magazine.

Leslie joined the faculty of the University of Michigan in 1971 where he served as chair of the voice department faculty and was director of the School of Music’s Division of Vocal Arts from 1986 until his retirement in 1999. After retirement, he continued an affiliation with the University of Michigan for another year in their then newly formed Vocal Health Center.

He loved his interactions with his students and was grateful for ongoing contact with so many. In recent times, he was honored to collaborate with Ann Arbor students from Skyline High School in the Legacies Project. The interview can be accessed via a YouTube interview.

He is survived by his wife, Mary Ellen Guinn.

Betty Hanson Passes

Bette (also Betty) Hanson, a Minnesotan trained to be an opera singer, found her life role in the tumultuous theater of civil rights in Birmingham, Alabama. She died on May 2, 2022 at the age of 95. Bette had lived in Washington, DC, for over 20 years before moving to her son’s home on Lake Anna at the outset of the pandemic.

Born Beverly Jane Johnson on August 10, 1926, Bette was raised in Duluth, Minnesota and played viola with the Duluth Symphony while still a student. She also studied voice and in 1944 went to the University of Iowa on a music scholarship. There she met her future husband, Roger W. Hanson of Rake, Iowa, who was then in medical school. After their marriage in 1948, they moved to Los Angeles, where Roger completed his Ph.D. in pharmacology and zoology at UCLA. Bette studied opera on scholarship at the music academy in Santa Barbara of the celebrated German soprano Lotte Lehmann.

After Roger was recruited in 1953 to the new University of Alabama in Birmingham to help build what would become one of the country’s foremost medical centers, he and Bette found themselves among a cohort of “outside agitators” defying the racial status quo in what Martin Luther King Jr. would call the most segregated city in America. As members of the state’s only functioning biracial organization, these white liberals acted on their conscience at a time when ignoring the color line brought them warnings from Ku Klux Klansmen under the escort of the Birmingham police.

Bette built an independent career playing viola for the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and taking starring roles in civic productions ranging from Madam Butterfly to Annie Get Your Gun. It was when she was given her own local television and radio shows that she found fame and at times notoriety as the media personality “Bette Lee.” She turned the “women’s affairs” beat away from fashion and food and into a platform of serious news, covering legalized abortion in Scandinavia, a Planned Parenthood bus clinic serving rural counties, and Japanese-American relations post-Hiroshima. Bette even did a broadcast in flight from an Air Force jet and, to cover the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, moved into a fallout shelter at the state fairgrounds with her mother.

Roger had grown accustomed to death threats, but when an anonymous phone caller told him, “We know which way your children walk home from school,” he took a research job with USAID in Indonesia to get his wife, son and daughter out of town. Following the CIA-backed coup against the government there, the family returned to Birmingham in 1965, and Bette resumed her challenging career in local journalism, as a fulltime news reporter, public radio news director and producer of documentaries, including one on Birmingham that won an award at the 1979 International Film & Television Festival in New York.

After retiring, Bette and Roger moved to Washington to be near their children and families. Roger died in 2002.

Lotfi Mansouri Passes

Lotfi Mansouri was best known for his years as opera director and especially as General Director of the Canadian Opera Company and the San Francisco Opera (1988-2001). He introduced surtitles to the opera house and for the Lehmann Tribute CD he spoke a wonderful reminiscence. He had, after all, studied (as a tenor) with Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West. Here is what he had to say: Lotfi Mansouri Speaks . He also wrote about Lehmann in his book, Lotfi Mansouri: An Operatic Journey. “she taught me to look deeper into the material, the atmosphere, the substance of the work.”

Mildred Miller Passes

We note with sadness the passing of Mildred Miller, one of Lotte Lehmann’s students. Below you can read a Miller obituary and you may want to sample her updated Wikipedia page.

Mezzo-soprano Mildred Miller has died at the age of 98. [just short of her 99th birthday]

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, she attended the Cleveland Metropolitan School District and graduated from West High School in 1942. She then studied at the Cleveland Institute of Music and the New England Conservatory.

She also went on to study at the Tanglewood Music Center and in 1946, made her opera debut as one of the nieces in the United States premiere of Benjamin Britten’s “Peter Grimes” at the Tanglewood Music Festival.

She went on to perform at the New England Opera Theater and following her graduation she left for Italy where she studied for several months. In 1949 she became an ensemble member of the Staatsoper Stuttgart and went on to make debuts at the Bavarian State Opera, the Vienna State Opera, the Edinburgh Festival, and the Glyndebourne Festival.

While in Germany she caught the eye of Metropolitan Opera General Manager Rudolf Bing, who offered her a contract but Miller initially rejected it due to the roles he offered. However, he returned with a better offer and Miller eventually made her Met debut in 1951. She went on to perform 338 performances with the company from 1951 to 1974. She sang a total of 21 roles and was well known for her “pants roles.” She made her Met debut as Cherubino in Mozart’s “Le Nozze di Figaro,” her most frequent role and one for which she holds the company record for the most performances, 67. She also sang Siébel in Gounod’s “Faust,” Nicklausse in Offenbach’s “Les Contes d’Hoffmann,” Octavian in Strauss’s “Der Rosenkavalier,” and the Composer in Strauss’s “Ariadne auf Naxos.”

Other roles included Suzuki, Lola, Rosina, and Carmen.

Outside of her Met career, the mezzo also performed at the Opern- und Schauspielhaus Frankfurt San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Cincinnati Opera, San Antonio Grand Opera Festival, Pittsburgh Opera, Kansas City Opera, Fort Worth Opera, and Opera Pasadena. She also sang at Carnegie Hall and at the White House and appeared on The Bell Telephone Hour, The Voice of Firestone, and The Ed Sullivan Show.

Miller also founded the Opera Theater of Pittsburgh and served as Artistic Director and a vocal coach for the company. In 1999 she stepped down from her position but continued to be involved. She also taught at Carnegie Mellon and gave master classes all over the world.

This is the Metropolitan Opera’s Miller obituary: The Metropolitan Opera mourns the death of mezzo-soprano Mildred Miller, an admired and cherished artist who sang 338 performances with the company from 1951 to 1974. Her Met debut as Cherubino in Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro was a first taste of what would become her most frequent role and one for which she holds the company record for the most performances (67). In all, she sang 21 roles with the Met and was particularly noted for “pants” roles which, in addition to Cherubino, included Siébel in Gounod’s Faust, Nicklausse in Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann, Octavian in Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier, and the Composer in Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos. Her broad repertory also encompassed roles such as Suzuki in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, Lola in Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana, and even two performances each of Rosina in Rossini’s Il Barbiere di Siviglia and the title role in Bizet’s Carmen. Following her Met career, Miller continued as a major force in the opera world, founding the Opera Theater of Pittsburgh and serving as teacher and mentor to generations of young singers. We extend our sincere condolences to her family, friends, and many admirers.

Norman Mittlemann Passes

Norman Mittelmann (25 May 1932 – 17 March 2019) was a Canadian operatic baritone who had an active international opera career from the 1950s through the 1990s. A winner of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions, he performed periodically at the Met from 1961 through 1984. Primarily active with opera houses in Europe, he was a resident artist at the Grillo-Theater in Essen, Germany (1959–1961), the Deutsche Oper am Rhein (1960–1964), and the Zürich Opera (1964–1982), in addition to appearing frequently with other opera houses internationally as a guest artist. His voice is preserved on several live complete opera recordings from the 1960s and 1970s.

Born into a Jewish family in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Mittelmann graduated from St. John’s High School in his native city. During high school he was a member of the Winnipeg All Star High School Football Team. He first studied singing with Canadian soprano Doris Lewis in Manitoba, before entering the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia on a full scholarship in 1950 at the age of 18. At Curtis he was a pupil of Martial Singher, Vladimir Sokoloff, and Richard Bonelli. In a 1961 Opera News interview he credited Singher with establishing the core of his technique, and enabling him to be successful professionally.

After completing his studies at Curtis in 1954, Mittelmann pursued graduate studies at the Music Academy of the West in Montecito, California in 1955 and 1956 where he was a pupil of Lotte Lehmann. He made his professional opera debut in Santa Barbara in 1956, portraying Count Almaviva in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro and Harlequin in Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos in productions directed by Lehmann. That same year he performed in the United States premiere of Darius Milhaud’s David at the Hollywood Bowl. In 1958 he portrayed Marcello in Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème for his first opera appearance in Canada in a production mounted by the Canadian Opera Company (COC). He later returned to the COC in a critically lauded portrayal of the four villains (Lindorf, Coppelius, Dappertutto and Dr. Miracle) in Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann in 1967, a production both in Toronto’s opera house and at Expo 67 in Montreal.

In 1959 Mittelmann won the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. However, he chose to delay his offered contract with the Met to pursue work in Europe. From 1959 until 1961 he was a principal artist at the Grillo-Theater in Essen, Germany. He made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera House as the Herald in Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin on 28 October 1961; and continued to perform periodically at the Met through 1985. Other roles he portrayed at the Met included Amonasro in Aida, Don Carlo in La forza del destino, Donner in Das Rheingold, Faninal in Der Rosenkavalier, Gunther in Götterdämmerung, the High Priest in Samson et Dalila, Jochanaan in Salome, Kothner in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Mandryka in Arabella, both Silvio and Tonio (in separate performances) in Pagliacci, and Valentin in Faust. His final appearance at the Met was on November 18, 1985 as Shaklovity in Modest Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina.

Mittelmann was a resident artist at the Deutsche Oper am Rhein from 1960 through 1964. He left that position to join the roster of resident artists at the Zürich Opera through 1982. A frequent guest artist with opera houses internationally, he also performed leading roles with the Bavarian State Opera, the Berlin State Opera, the Lyric Opera of Chicago (debut as Ruprecht in Prokofiev’s The Fiery Angel in 1966), the Paris Opera, the Royal Opera, London (debut as Germont in La traviata in 1965), the Teatro Colón, and the Vienna State Opera. In 1970 he created the role of Daniel in the world premiere of Paul Burkhard’s Ein Stern geht auf aus Jaakob at the Hamburg State Opera. He performed in several productions with the San Francisco Opera from 1972 until 1979, appearing as Amonasro, Barnaba in La Gioconda, Germont, Nelusko in L’Africaine, and Rodrigo in Don Carlo. In 1983 he performed the role of Shishkov in the United States premiere of Leoš Janá?ek’s From the House of the Dead with the New York Philharmonic. His final opera performance was in 1991, although he continued to work as a concert performer for several more years.

Mittelmann lived in retirement in Palm Springs, California where he sold real estate and owned and operated a restaurant.

Bonney Murray

Bonney Murray, soprano, was born in Middletown, Ohio, and studied both singing and dancing in Middlewon until her teens. She continued her studies in California, and subsequently worked with Lotte Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West. Recognized for performing in a wide variety of the pops repertoire, she sang the works of Rodgers and Hammerstein, Lerner and Loewe, Cole Porter, etc. with numerous orchestras, including those of Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Minnesota, and St. Louis. Her musical comedy credits list leading roles in Most Happy Fella, Carousel, Showboat, Brigadoon, Song of Norway, The Merry Widdow and Call Me Madame. She sang in a command performance of The Chocolate Soldier for Queen Elizabeth in Vacouver, BC. In addition, she appeared in leading roles in operas such as La Traviata, Carmen, La Boheme, and I Paliacci.

This is what Lotte Lehmann said of her: “There is only one who scarcely needs me, or at least only in so far as every singer needs a stage director: Bonnie Murray, who sings Mélisande [in the Music Academy of the West performance of Debussy’s opera]. She has everything within her—it is there, one has only to call it forth. To “call” it out of the others, I sometimes seem to need a trumpet…. But then to see how everything is working out, and how something wonderful is emerging—Ah, what a joy!”

Carol Neblett Passes

Carol Neblett, a soprano who sang numerous roles at New York City Opera and the Metropolitan Opera, as well as one particularly attention-getting one in New Orleans that included full nudity, died on Nov. 23, 2017 at her home in Los Angeles. She was 71.

Her son, Stefan Schermerhorn, said that the specific cause was not known but that she had been in ill health.

Ms. Neblett sang all over the world after making her City Opera debut as Musetta in Puccini’s “La Bohème” in 1969. She sang the title role in Puccini’s “Tosca” more than 300 times, the first in 1976 at the Lyric Opera in Chicago with Luciano Pavarotti as Mario Cavaradossi. She sang an excerpt from “La Fanciulla del West” (again by Puccini) with Plácido Domingo for Queen Elizabeth II’s 25th Jubilee celebration in 1977.

Carol Lee Neblett was born on Feb. 1, 1946, in Modesto, Calif., into a family that seemed to preordain a musical career. Her father, Norman, was a piano technician, and her mother, the former Annette Brown, was a personal assistant to the violinist Jascha Heifetz. Her grandmother Leona Neblett played chamber music with Heifetz and began teaching her granddaughter the violin when Carol was 2.

As the family story goes, Carol was asked to play for Heifetz; she became flustered and began to sing instead. Heifetz recognized her singing ability and encouraged her thereafter.

Ms. Neblett took private lessons from William Vennard, a professor at the University of Southern California, and attended El Camino College for a year, but while still a teenager she was invited to join the Roger Wagner Chorale. She made her Carnegie Hall debut with that group at 19. She also studied privately with Lotte Lehmann.

The impresario Sol Hurok, who presented many notable entertainers, took her onto his roster and encouraged her to try opera. Her City Opera debut in 1969 impressed Allen Hughes, who reviewed the performance for The Times.

“Although the part of Musetta does not reveal a great deal about the breadth of a soprano’s ability and artistry,” he wrote, “Miss Neblett’s performance suggested that she might have considerable operatic potential.” He also became the first of many critics to comment on her physical beauty.

“Since she is good-looking as well as talented,” he wrote, “she would appear to have a promising future ahead of her.”

Almost 20 years later, in 1988, when she performed her first Aida with Opera Pacific, Martin Bernheimer of The Los Angeles Times wrote, “Tall, lithe and eminently sympathetic, she must be one of the most attractive — and most formidable — Aidas in history.”

Her looks, she found, were one of those blessing-and-a-curse things. The Chicago Tribune cited her in a 1987 article on women’s body image.

“Carol Neblett, a soprano with the New York Metropolitan Opera, finds that the same media that helped her get to the top also makes her self-conscious, that she’s competing with her own body, she says,” the article reported. “Frequently reviewers may comment, ‘Ravishingly beautiful … with a voice to match,’ as opposed to the other way around.”

In any case, she worked steadily for decades, making her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1979 in Wagner’s “The Flying Dutchman.” Harold C. Schonberg, the critic for The New York Times, found a lot to detest about that production, but not Ms. Neblett’s performance.

“The surprise of the evening was Carol Neblett, making her debut as Senta,” he wrote. “She is no newcomer to New York and she has done some fine work at the City Opera, but never has she unleashed so powerful and commanding a voice.”

“I was not singing well for a long time,” she told The Los Angeles Times in 1988, adding: “I had gotten into some bad vocal habits. Also, I saw myself on television and didn’t like the way I looked while singing.”

She thought of retiring, she said, but with the help of a new vocal coach she recommitted herself and continued performing.

Ms. Neblett’s first marriage, to the cellist Douglas Davis, ended in divorce in 1968. In 1973 she married the conductor Kenneth Schermerhorn, who at the time was leading the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra. The New York Times pronounced them “music’s newest Supercouple.” They were divorced in 1979. She married Philip Akre, a cardiologist, in 1981; they divorced in 2004.

For the last 13 years Ms. Neblett had taught at Chapman University, where she was an artist in residence.

Though she stopped performing on major opera and recital stages in 2005, she did sing occasionally thereafter. In 2012 she even made her stage musical debut in a production of Stephen Sondheim’s “Follies” at the Ahmanson Theater in Los Angeles, playing a secondary part that gave her one duet.

“When she began singing,” Carol Jean Delmar wrote in her review for Opera Theater Ink, “everyone in the audience knew they were hearing something special.”

Maralin Niska Passes

Maralin Niska, a lyric soprano whose mesmerizing stage presence and command of dozens of roles made her a mainstay of New York City Opera in the 1960s and ’70s, died on Saturday (July 13, 2016) at her home in Santa Fe, N.M. She was 89.

Her husband, William Mullen, confirmed her death.

Ms. Niska, who joined the company in 1967, had a dark, supple, powerful voice, heard to advantage in her performances as Cio-Cio-San in Puccini’s “Madama Butterfly,” Violetta in Verdi’s “La Traviata” and the title role in Richard Strauss’s “Ariadne auf Naxos.” But it was her dramatic gifts and movie-star looks — The Daily News of New York once said she resembled “Ava Gardner of the love goddess years” — that earned her a special place in the hearts of opera fans.

Ms. Niska appeared in 29 lead roles with New York City Opera, more than any other singer. None of the roles made a bigger impact than her breakout performance in 1970 in Janacek’s “The Makropulos Affair” as Emilia Marty, an opera singer who has lived for 342 years in a series of guises after drinking a magic potion.

“Miss Niska was sensational,” the critic Harold C. Schonberg wrote in The New York Times. “It was clear that her mother was a vampire, her father a lycanthrope. She looked like a Gibson girl with the best features of both her parents. Implacable, beautiful, cold, selfish, hard, amoral, she lowered the temperature of the stage to near absolute zero.”

Katsuumi Niwa Passes

Katsuumi Niwa was born on 3 August 1938 and died on 29 January 2019 (80 years). Professor Niwa taught voice for many years at Nihon University. He was known and appreciated in three vocal areas: helden tenor, baritone, countertenor. He sang countertenor in Minao Shibata’s vocal works, as well as traditional Japanese contemporary opera and European Baroque music. As a tenor and baritone he was respected in French vocal music (mélodie). An active member of NATS and JARS, he often represented Japan at international festivals and conferences.

He performed in many world premiers of both opera and song, and sang at Lincoln Center’s Fisher Hall in “Himiko” as the Earth Diety; sung John Cage in New York, Pinkerton in Mme. Butterfly in Japan, and successfully appeared as helden-tenor in Wagner operas there. Dr. Niwa has also taken part in films including “Tora-san, The Go-between) 1985.

Part of a group of Japanese singers that Dr. Jan Popper brought to UCLA for study under a Fulbright fellowship, Niwa went on to study with Lehmann, and Jennie Tourel.

His other teachers include Yoshiko Fukuzawa, Takeshi Isogaya, and Jan Popper.

You can listen to Katsuumi Niwa discussing his studies with Mme. Lehmann in two interviews. First Interview Second Interview

William Olvis Passes

William Edward Olvis, whose tenor voice rang from Hollywood to Broadway to the New York Metropolitan Opera, has died of throat cancer. He was 70.

Olvis, who was born in Hollywood and reared in Glendale, died Nov. 27, 1998, at his home near Redlands, where he had retired, according to an announcement Monday by his son, motion picture composer William Patrick Olvis.

Educated at USC and Occidental College, Olvis set out to become a lawyer but became interested in music instead. Earning the Atwater Kent Award, a major prize for voice, in 1949, he decided to make singing his career. He studied at the Music Academy of the West with Lotte Lehmann, then in Los Angeles, and later won a Fulbright scholarship to study in Rome.

Drafted into the Navy, Olvis was a sailor in 1949 when an admiral’s wife who heard him sing told him prophetically: “In 10 years you’ll be singing at the Metropolitan Opera.”

Right on schedule, in 1959, he sang the starring role of Don Jose in “Carmen” at the Met.

Olvis first gained national attention in 1954 when he was hired to replace tenor Mario Lanza in the film “Deep in My Heart,” the story of composer Sigmund Romberg.

The developing tenor later sang the lead in “Song of Norway” on Broadway and toured with the stage company.

During his tenure with the Metropolitan Opera in the late 1950s and early ‘60s, Olvis sang the tenor lead not only in “Carmen” but also in such classic operas as “Aida,” “Madame Butterfly,” “La Boheme” and “The Flying Dutchman.”

In later years, he sang with the Dusseldorf Opera Company in Germany.

After returning to California, Olvis continued to make special appearances. In 1988, he sang in quartet with Anita Protich, Jacalyn Bower and James Patterson at a Pacific Symphony concert in Irvine Meadows Amphitheatre, launching the Orange County Centennial.

A Times reviewer praised Olvis after that concert for his “healthy, full-throated and nicely gauged vocalism.”

Olvis debuted at the Hollywood Bowl in 1953 with the Los Angeles Philharmonic in a pops concert highlighting the music of “Showboat.”

When he sang in concert five years later at the San Gabriel Civic Auditorium, a Times critic praised the tenor’s vocal range: “The Olvis voice is a fledgling heldentenor with an amazing lower register, a rich, robust instrument, yet one that can shave itself down to engaging softness.”

In addition to his son, Olvis is survived by his wife, Noreen.

Harve(y) Presnell

Here’s what Lotte Lehmann had to say about him: “At the moment I am working like mad at the Academy. We are rehearsing Act II of The Flying Dutchman. The young baritone, Harve Presnell, is absolutely astonishing. If he does not become one of the great ones some day, then I understand nothing at all. Up until now it was just a very beautiful voice; but I have managed to awaken him to the realization that singing is not the end, but rather only the beginning. He is gradually overcoming his inhibitions, and today he was so good that I am in seventh heaven.”

Harve Presnell, whose rich operatic baritone thrilled audiences in the stage and film versions of “The Unsinkable Molly Brown” and who made an unexpected return to the screen as William H. Macy’s overbearing father-in-law in “Fargo,” died Tuesday, June 30, 2009, in Santa Monica, Calif. He was 75 and lived in Livingston, Mont.

The cause was complications of pancreatic cancer, said his agent, Gregg Klein.

Mr. Presnell, who trained as an opera singer, brought an imposing physical presence ? he stood 6 feet 4 inches ? and a resplendent voice to the Broadway stage, delivering a star-making performance as Leadville Johnny Brown in “The Unsinkable Molly Brown.”

“He anchored that show, with a down-to-earth quality that played perfectly against Tammy Grimes’s wonderfully eccentric style,” said Miles Kreuger, the president of the Institute of the American Musical. “It’s a pity they didn’t give him more larger-than-life roles because he had the physical presence and the voice for it.”

It was Mr. Presnell’s misfortune to arrive on the scene as the golden age of the musical was in its twilight, and roles worthy of his voice were few and far between.

His triumphant debut led to unsatisfactory film roles and a somewhat stunted career appearing in national tours of Broadway musicals, most notably as Daddy Warbucks in “Annie,” a role he also played on Broadway and reprised in the ill-fated “Annie 2: Miss Hannigan’s Revenge.”

The Coen brothers gave him a second Hollywood career as a character actor when they cast him in “Fargo” in 1996. That role led to a series of meaty film parts, including Gen. George C. Marshall in “Saving Private Ryan.”

George Harvey Presnell was born in Modesto, Calif. After graduating from Modesto High School, he studied voice at the University of Southern California, the Music Academy of the West with Lotte Lehmann and embarked on a concert career.

In the 1950s he sang with the Roger Wagner Chorale and performed on their recordings for Capitol, including the Christmas album “Joy to the World,” “Folk Songs of the New World” and “Folk Songs of the Frontier.”

Mr. Presnell also sang the baritone part in the 1960 recording of Carl Orff’s “Carmina Burana,” with Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra.

After hearing Mr. Presnell sing, Meredith Willson created the part of Johnny Brown as a star-making vehicle for him. When “The Unsinkable Molly Brown” opened in 1960, with Ms. Grimes in the starring role, Mr. Presnell planted his feet and let audiences have it with both barrels as he boomed the songs “Colorado, My Home” and “I’ll Never Say No.” He repeated the role in the highly successful film version, released in 1964, with Debbie Reynolds as Molly.

It was a once-in-a-lifetime role. In 1965 he tried his hand at a straight western, “The Glory Guys,” but he was desperate to sing, which helps explain his appearance in the Connie Francis film “When the Boys Meet the Girls.”

The film of “Paint Your Wagon” (1969), with bizarre casting that mingled Lee Marvin, Clint Eastwood and Jean Seberg, delivered the golden opportunity to sing the unforgettable ballad “They Call the Wind Mariah,” but by the 1970s his Hollywood adventure had seemingly come to an end.

For the next decade Mr. Presnell toiled in the minor leagues of musical theater. He toured with “Annie Get Your Gun” and “On a Clear Day You Can See Forever.” He played Rhett Butler in a short-lived musical version of “Gone With the Wind” in London. His second crack at Broadway came when John Schuck left “Annie” in 1980, allowing him to step in as Daddy Warbucks, a role he had played in touring companies.

The breakthrough role of Wade Gustafson in “Fargo” rejuvenated a film career that had barely had time to get started in the 1960s. Mr. Presnell, whose face and voice had weathered with the years, suddenly found his services as a character actor in demand in film and on television for roles requiring a powerful presence and a whiff of menace.

He had recurring roles in the television series “The Pretender” and “Andy Barker, P.I.” and appeared in the films “Larger Than Life,” “Face/Off” and “The Legend of Bagger Vance.” His most recent film role was as a senator in “Evan Almighty.”

Mr. Presnell’s first marriage ended in divorce. His survivors include his second wife, Veeva.

Marcella Reale Passes

Though blessed with a beautiful voice and a successful opera career, Reale is perhaps best known for her decades of teaching in Japan.

Reale recorded a song for the Lehmann Tribute CD:

The American soprano, Marcella Reale, sang two seasons with Opera Australia in 1968 and 1969 in the roles of Senta, Donna Anna, Minnie and Elisabeth. On news of her passing (January 17th, 2021) she was remembered in Australia by “her larger than life personality, her intense performances and her generosity to colleagues and staff”. Of course, her international career and vast array of roles speaks for itself. She was awarded the “Puccini d’Oro” for her commitment and success in the Maestro’s repertoire. In Treviso, she was awarded the “Mario del Monaco” prize for the best verismo interpreter along with Gianni Raimondi.

She was a great verismo interpreter as well as performing the standard Leading Ladies of the Italian, French and German repertoire. (Her favourite role was Katerina Izmailova in Shostakovich’s opera.)

Born in Brooklyn, New York, July 17th, 1929, to Italian parents, her early career saw her as Mimi in San Francisco at age 14 followed with Cio Cio San the next year – yes … the actual age of Puccini’s heroine! These were overseen by her main voice and interpretation teachers – Armand Tokatyan and Lotte Lehmann. She received a Fulbright Scholarship, which enabled her to continue her studies at the Hochschule für Musik in München.

Marcella’s main career began in 1957-58 at the State Theater of Heidelberg. Thereafter she appeared at the Aalto-Musiktheater in Essen (1958-59) and the Theater of Krefeld. 1961 marked the first time she sang in Italy, at the “Verdi” Theater in Trieste. Then she appeared in other theaters around Italy (Teatro Regio di Parma, Teatro di San Carlo in Naples) as well as the New York City Opera. She also performed in San Francisco, Seattle, Tel Aviv and Athens.

Her colleagues on stage included, Placido Domingo, Jose Carreras, Mario del Monaco, Franco Corelli, Alfredo Kraus, Richard Tucker, Tito Gobbi, Birgit Nilsson and Jon Vickers (Alfredo to her Violetta!). In 1991 she was invited to Japan to perform and give masterclasses – returning in 1993 to stage Scarlatti’s IL MITRIDATE EUPATORE – the Japanese premiere. She remained in Tokyo actively teaching until 2017 when she returned to the USA.

Marcella was a wonderfully generous soul with an electric personality on and off stage. She had a strong presence and was incredibly supportive of young performers – though with definite opinions which were supported by her personal experiences in performance. She was an encyclopaedic resource which I tapped on many occasions. One had to merely mention a role and out would pour a font of valuable information about the character, approach to singing the role and what to convey to the audience when not singing!

She had an enormous repertoire of anecdotes … Learning Mascagni’s ISABEAU in four days as a Stand-by for an ailing Marcella Pobbe in Napoli in the early 1960s. When Pobbe heard that Reale was ready to replace her in the production she ‘surprisingly’ gained her health. As a token of thanks, Management gave Marcella twenty performances of Cio Cio San (a role she sang over, a documented, three hundred times) At the time, cash was not permitted to leave Naples, so Marcella used the twenty performance fees to purchase a magnificent cognac diamond (surrounded by emeralds and white diamonds) ring. That was pure Diva mentality.

In Buenos Aires, she replaced Marie Collier as Tosca. In 1975, whilst performing the title role in ADRIANA LECOUVREUR in Europe, she was called to replace an ailing soprano that night at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. Marcella boarded a plane and, an hour before landing, applied her Cio Cio San makeup and wig. From the tarmac, she received a police escort to the theatre – which had held the curtain almost an hour for her arrival. As the curtain rose, she had not met the conductor or any of the cast. Her Pinkerton was Jose Carreras.

Her beautiful, tiny face is clearly seen as Mimi in the Musetta sequence in the M.G.M. film of the life of Australian soprano Marjorie Lawrence “Interrupted Melody” in 1955. Her only Liu’s in TURANDOT were with Birgit Nilsson and Franco Corelli. That night, Marcella had a raging fever and dropped the dagger twice in her suicide scene. She had not met either Nilsson or Corelli and, as the curtain rose, Franco Corelli shook her tiny hand and introduced himself – in view of the audience.

Shirley Sproule

Shirley Sproule, soprano, was born in Canada and trained and sang there until first studying opera and Lieder with Lehmann at the MAW in 1953. She continued there with Lehmann, working in the winters as well as the regular summer sessions and after 1956 sang in Europe (Munich, Mainz, etc.). She sang in Lehmann’s London Masterclasses in 1957.

Here’s what Lehmann had to say about her: “

“And the Senta [Lehmann was preparing scenes from Wagner’s Flying Dutchman], Shirley Sproule—so touching and so lovely. I would never have believed it possible that I could live like this through others, that I would enjoy it so. I have always resisted the idea of living “vicariously.” But that is probably our destiny as we grow old: that we can find joy in that. To be able to transform quite good singers into artists—that has something creative and deeply satisfying in it.”

In 1965 Dr. Sproule returned to Regina, Saskatchewan to teach voice and sing there. In 1970 she began her doctoral studies at the University of Arizona in Tucson, breaking her work there to cover sabaticals and sing in Canada in 1971-72. After she returned and finished her doctoral degree in Tucson, she stayed there, teaching until her retirement.

Here’s Dr. Sproule’s tribute to Lehmann:

Luba Tcheresky Passes

One of Lehmann’s favorite students, Luba Tcheresky, passed away on December 2023 at the age of 101. First, you can hear her speak about Lehmann and then you’ll see her in the photo below. After that is the obituary.

Luba Tcheresky

April 17, 1922 – December 16, 2023

Luba passed away peacefully and gently at 9:48 AM in Calvary Hospital in the Bronx.

Luba’s mother had a chance to emigrate to America when Luba was only 4 months old and considered Luba too young to take along on such a long and arduous voyage. She would be sent for at a later date. Luba had a happy childhood being raised by a much-loved grandmother and grandfather who was related to the Romanovs, and an Uncle Vanya, on their country estate in Byelo-Russia. She was schooled in a Warsaw convent and thought she would be returning “home” in time. However, when she was 8 ½ years old she was transported, weeping and screaming, to the port of Gdansk and shipped off with a nametag pinned to her coat-destination: Detroit, Michigan. The intrepid little girl suffered a bout of chicken pox onboard and was put ashore in London to be hospitalized for 10 days before journeying on to a family she didn’t know: her mother, step-father and two older sisters.

When she was 9 her mother enrolled Luba in English classes in an elementary school and once her English improved she was double-promoted from the 5th to the 6th grade and then to the 7th. Her mother also made sure Luba studied ballet, piano and Russian dance, privately…and all Russians learned to play the mandolin! At Cass Technical High School she majored in piano but was extremely rounded in her musical studies that included theory, orchestration, violin and trumpet. The faculty auditioned singing voices to form a girls’ trio and Luba was chosen for the lead voice- and so “The Novelettes” were formed! They made their own arrangements and added guitar, string bass and accordion (Luba learned the accordion) which afforded them more jobs and interesting venues for performance.

Voice then became the major interest in Luba’s life and she began serious voice study, winning numerous local and state competitions. She graduated from Cass Tech before the age of 16 and went on to attend the Detroit Conservatory of Music and Wayne University. She added studies in French, Italian and German to the Polish and Russian she had learned at home and found time to also conduct and arrange music for a 4-part choir! All along Luba’s mother was the force and inspiration behind Luba’s efforts. Katherine Lebedev, dubbed the “primadonna” of the Russian colony in Detroit, often took Luba to her own performances with the Detroit Balalaika Orchestra, the Russian Orthodox Church and to the Russian plays in which Luba also took part. At one point Luba coached her own mother on an aria from Mazeppa that she was to sing! She particularly enjoyed singing at the many Russian concerts and balls put on by the Russian community and acting in their classic puppet theater. This experience came to great use later in New York when she was asked to sing for the White Russian Ball along with Nicolai Gedda! During this period in Detroit, a visitor from New York heard Luba sing and advised her mother to send Luba to NYC to study the bel canto method with a teacher who had just arrived from Italy. This was arranged and after a few years Luba married and moved with her artist husband, Richard Sortomme Jr., to his home in California where their two children were born.

Ms. Tcheresky accepted a scholarship with Carl Ebert, director of the Opera Department at University of Southern California. She made her operatic debut there as First Lady in Mozart’s “Magic Flute” under the baton of Alfred Wallenstein. She also sang the lead in George Antheil’s “Volpone”. At the same time she was studying voice with Major Herbert Wall (one of the last students of Jean de Reszke) and added Madama Butterfly and Elizabeth in Tannhauser to her repertoire, and was asked to sing Elizabeth at the Wilshire Ebell Theater in L.A. She was the winner of a 13-week long television singing contest. She also won the Glendale Symphony auditions singing “L’altra notte” from Boito’s ”Mefistofele” and “Dich teure Halle” from Wagner’s Tannhäuser. She was chosen by Lukas Foss to sing Allan Berg’s early songs with the Los Angeles Chamber Symphony.

A woman who heard Luba with the Glendale Symphony Orchestra suggested that she sing for Lotte Lehmann who was auditioning singers for her master classes at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara. Luba won a 3-year scholarship and became one of Lehmann’s favorite protégés, spending much time with her and her friend, Frances Holden, at their home “Orplid”, and even being invited to vacation with them. During this time Luba had great success as Cherubino (Marriage of Figaro) and Rosalinda (Die Fledermaus) with Maurice Abravanel conducting at the Lobero Theater and Redlands Bowl. She also sang numerous recitals and oratorios throughout the west coast and the roles of Butterfly, Elizabeth in Tannhäuser, Tatyana in Eugene Onegin, Lisa in Pique Dame and Natasha in Dargomyzshsky’s Russalka (The Mermaid). She may well be the only soprano to have sung BOTH Mermaids: the Dargomyzshsky and later in Germany, the Dvorak.

Ms. Tcheresky placed in the Metropolitan Opera Regional Competition and was then sent to NY by the Music Academy of the West with letters of introduction for auditions and enough money to last about 3 months. Luba did not want to go to Europe at this time because she refused to leave her children at their tender ages for such an extended trip so far away. An agent who heard Luba sing in Santa Barbara was extremely interested in her and told Lehmann that if Luba would come to NY he would help get her auditions. However, he turned out to be a great disappointment -he took all her letters but did not come forth with auditions.

Money running out, she started to “temp” and also took a job singing the Russian “songs her mother taught her” at a Russian supper club whose owner had heard her in the Catskills. She began to get her own auditions and sang Santuzza (Cavalleria) with the Bronx Opera Co. and Tosca for the Metropolitan Opera Guild. George Schick of the Metropolitan wanted to hear her and praised her for having sung a “great” audition but advised going to Europe first and gaining more experience. A patron financed her audition trip and Luba got a “star” contract on her very first audition, in Düsseldorf -without an agent! She sang only two arias on stage: “Sola, perdutta, abbandonato” and “Dich, teure Halle” and the directors of the opera house immediately took her to their office and offered her the lead role in Dvorak’s “Rusalka” which was to be the last premiere they would mount to end their 11-year rein managing Düsseldorf and Duisburg and then they would be taking over management of the Zürich State Opera. They asked her at the same time to open the season for them there in the fall. Luba asked if they didn’t want to see her resume and they answered, “no, we know what we heard -we haven’t heard a voice like yours in 50 years!”. And when she mentioned that the money they were offering her wasn’t very much in American money, they offered her more, plus fare both ways from NY! And so she closed Düsseldorf as Rusalka and began her stint at the Zürich Staatsoper. She sang Donna Anna, Maddalena, Micäela there and guest appearances elsewhere.

Returning to NY because of family and personal reasons, Miss Tcheresky was engaged by Gian-Carlo Menotti to appear as Mme. Euterpova in his opera “Help, Help, the Globolinks!” at the ANTA Theater on Broadway for a month run. She had already sung his “Maria Golovin” and “The Consul”. Thomas Martin engaged her for Fanciulla del West (Minnie) and Santuzza in Cavalleria. She appeared as guest artist in the NY Library Concert Series, the American Landmark Festival Series, toured as a soloist with the American Airlines sponsored Concert Series throughout the U.S. and guest artist with various symphony orchestras.

In addition to her opera and concert career in both Europe and the U.S., Miss Tcheresky appeared in a number of Broadway musicals including “Carousel” with John Raitt, and Bernstein’s “Candide” and Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Mikado”.

Luba shared a close personal and professional rapport with the renowned composer Vernon Duke (Vladimir Dukelsky). They met when she was a guest at one of his musical soirees in Los Angeles and he became a “fan” of her singing and a great friend. While she was studying with Lotte Lehmann in Santa Barbara, Vernon wrote (he was a great letter-writer and Luba has a scrapbook full of his letters!) that he was would be coming to hear her Cherubino. He was bringing his lyricist along and would stay the weekend -would she make hotel arrangements and get another girl so that they would have a foursome for dinners? So at the cast party after “Marriage of Figaro” Luba introduced Vernon to her friend and fellow-student Kay McCracken and soon Luba was singing at the “Marriage of Vernon” -and Kay- and as maid-of-honor, pushed Vernon up the aisle!

Later in Vernon’s visits to NY he enjoyed hearing Luba sing his “April in Paris” and other Duke favorites at some of her performing venues. Her collaborations with Vernon Duke included singing Russian translations of Broadway musicals for Radio Liberty. Vernon translated them, played the piano, narrated and even SANG the ”Pineapple Duet” (Ananas) from Cabaret with Luba -in Russian, of course!

Vernon also liked following Luba’s son’s (Richard Sortomme III) progress as a young violinist and often accompanied him on the piano during visits to their home. Years later at a ceremony inducting Vernon Duke into the Library of Congress, Richard played Vernon’s Violin Sonata and String Quartet.

Maria Callas personally selected Luba as one of 20 singers (from 500 auditioned!) to participate in her Lincoln Center (Juilliard) Master Class Series. She was later chosen to be one of the first few singers from the class to be featured on the first issue (EMI) of the classes.

Miss Tcheresky has sung under the batons of Lukas Foss, Thomas Martin, Maurice Abravanel, Alfred Wallenstein, Christopher Keene, Laszlo Halasz, Erede, Leonard Bernstein, G. Pattane, Hans Swarofsky, Nello Santi and others.

Regarded as one of the best singing teachers in NYC, Miss Tcheresky has been highly successful in building and nurturing young voices as well as devising therapeutic techniques to rebuild and maintain more mature voices.

Miss Tcheresky has two children of whom she is very proud -her daughter Freya Pruitt, a minister in the Christian faith and writer and developer of rising personalities, and her son, Richard Sortomme III, violinist and composer. She is deeply thankful to them for their love, constant encouragement, support and participation in her life and career.

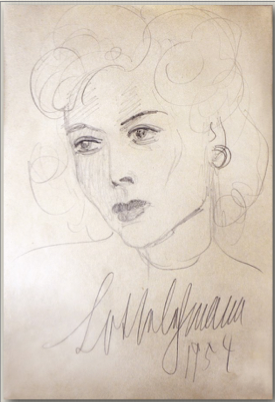

Benita Valente Has Passed

Born 19 October 1934, Benita Valente died on 24 October 2025. Because she’d studied interpretation with Lehmann for six years, Valente was an obvious person to write the Preface to the iBook Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy Volume 2. Here, along with the painting that Lehmann herself drew of her student, a few photos, and an actual master class that Lehmann taught to Valente, that Preface. That is followed by the New York Times obituary.

“On the long path to becoming a professional singer, I was fortunate to work with a number of exceptional musicians. My high school music teacher in Delano, California, Chester Hayden, was the first among them, and it was he who led me to the legendary German opera and Lieder singer Lotte Lehmann.

“Lehmann, who had just retired from the stage and was heading the vocal program at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, accepted me for the nine-week summer session in 1953. Based on what she heard in our voices, she created an individual recital program for each singer whom she took on as a student. This was a special and unique gift, reflecting her largesse, and it proved to be of great value to me as I continued in my studies.

“In all, I spent four summers at the Academy. After the second summer, I moved to Santa Barbara and, shortly after that, was accepted at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where I studied with baritone Martial Singher, but continued at the Academy for two more summers.

“The schedule there was intense. From Monday through Thursday, we would prepare the repertoire that Lehmann had chosen for us for her master classes, working with soprano Tilly de Garmo on vocal technique and with her husband, conductor/coach Fritz Zweig, at the piano. They were among many gifted musicians who had fled Nazi Germany for the United States, and we were so fortunate to have the opportunity to learn from them.

“On Friday and Saturday, Lehmann held two-hour master classes on interpretation, open to a paying audience and held in a large, elegant room of the Spanish-style mansion located on a cliff near the Pacific Ocean. Fridays were devoted to German and French art songs and Saturdays to operatic arias and scenes. The roughly eighteen students sat in the hall observing, and Lehmann (whom we always called “Madame Lehmann”) would call us to the stage individually, or as a group for opera scenes, to perform selections from the repertoire selected for study that week. Occasionally, when she heard a vocal problem, she would refer us to Tilly, and, during one summer, to tenor Armand Tokatyan.

“The first Lied I sang for Lehmann in 1953 was Schumann’s “Die Lotosblume,” set to a poem by Heine. Because I had not heard German spoken or sung before, it took me two weeks to memorize the song, but there was a lotus pond down the road from the Academy that I used for inspiration. I also sang “Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht” by Brahms, which struck me deeply because my mother had died in 1954. Lehmann must have felt my strong connection with the music, for she was gentle with her critique.

“In a professional career of over four decades, Lehmann had shown an amazing gift for taking on virtually any role or song and making it her own. She was always guided by the text, which she considered to be the key to expression and color. As her students, we reaped the benefits of this vast experience. We had to memorize each piece, and if we forgot the text Lehmann, puzzled, would say: “I would rather have forgotten the music than the words.”

“Sometimes, when we just couldn’t achieve the results she wanted, Lehmann would step onto the stage to sing an aria or song, often an octave lower, that we were working on. On days when her allergies were not bothering her, she would sing it as written. Watching and listening to her, we were mesmerized by her ability to transform herself magically into another persona and overwhelmed by the depth and range of emotion she expressed.

“She opened us up to the many possibilities of interpretation and made it clear that she did not want us to copy her, but to develop our own means of expression. By the end of each class, I had experienced such a range of emotions that I found I had developed a splitting headache and had to go back to my room to lie down.

“Lehmann had sparkling blue eyes and wore elegant but simple ankle-length dresses, sometimes with a scarf of the same beautiful material. When each session was over she would sweep out of the room past the audience, surely aware of the impression she had made on us, her spellbound students. Yet she was, at the same time, a warm and friendly presence and took a personal interest in her students, being especially curious about our love life. “Haf you never been in love?” she would ask if we lacked the requisite romantic emotion in a song, and she would rhapsodize about moonlight, innocently translating the German word “Mondschein” into “moonshine.”

“Learning how to act and move on stage was another aspect of our training. We were all somewhat awkward and needed to learn the basics. I remember being taught how to die in operatic fashion by our handsome acting coach, tenor Carl Zytowski, and one day Lehmann said to me in class, “Benita, I have heard that you have learned to die beautifully. Please die for us”—which I did! The acting lessons were valuable for our opera scenes and for the complete operas that were staged once a summer, though my skill in dying was not called for in the roles I was given: Barbarina in Le Nozze di Figaro, the Echo in Ariadne auf Naxos, and Adele in Die Fledermaus.

“Another major influence at the Academy was Lehmann’s older brother, Fritz Lehmann, a highly regarded vocal coach who came to all the master classes and worked individually with some of us in his home in Santa Barbara, in the presence of his warm and loving wife, Theresa. Fritz shared my great love of Mozart and recognized that Mozart’s arias and songs were ideally suited to my voice. How right he was! Mozart became the cornerstone of my operatic career, with such roles as Pamina in Die Zauberflöte; Susanna, and later the Countess, in Le Nozze di Figaro, and Ilia in Idomeneo.

“In addition to the summers at in Santa Barbara, I spent a winter there as part of a small group of singers working with Lehmann solely on Lieder. In this more intimate setting with students she knew well—at the end of each master class— Lehmann would sweep out of the room in her usual graceful fashion, pass us by and say: “Goodbye children.” Eventually I summoned up the courage to respond: “Goodbye, Mother.” One day there was an outsider in the room and I didn’t want to embarrass anyone, so I said nothing. Lehmann walked by me, looked at me, and, with a twinkle in her eye, silently mouthed the words “Goodbye, Mother.”

“Lehmann’s immense curiosity drew her into many areas of life. She enjoyed creating art and did a painting for each song of Schubert’s song cycle, Winterreise. One of those paintings hangs in my studio. She loved gardening and made the tiles for the steps of her garden. She was a frequent letter writer, her handwriting large and sprawling and her words revealing her characteristic truthfulness and emotional openness.

“Lehmann had a great love of animals. She owned two myna birds who could be heard from the garden imitating her speaking voice exactly. Once Lehmann asked soprano Shirley Sproule, who was my colleague and voice teacher at that time, to drive her to Los Angeles, and I happily went along, thrilled to be in her company. On our return we passed a schoolyard. Lehmann spotted a crow perched on the monkey bars. Although we assured her that the bird was fine, she later apparently worried that it was caught in the bars and insisted that her friend Frances Holden drive her back to the schoolyard. No bird remained—it was free!

“In my current life as a teacher of voice, I think often of Lotte Lehmann, of her larger-than-life personality, her magnetism, her ability to become different people on stage. No wonder such major creators as Richard Strauss, who composed music for her, and Arturo Toscanini, who conducted her in performance, were so entranced by her! For me personally, one of Lehmann’s most important gifts was to open my path to loving the Lied and the song repertoire in general. Her equal commitment to opera and art songs has inspired me to follow the same path, adding chamber music, oratorio, and contemporary works to my own repertoire. I have accepted as key her principle that the words lead the way to the expression and color that the composer intended.

“Lotte Lehmann, along with pianist Rudolf Serkin, who was a mentor to me at the Marlboro Music School and Festival in Vermont, and soprano Margaret Harshaw, with whom I studied from 1969 until 1995, two years before her death, were the musical greats who inspired me in my life in music. Passing on their artistic vision to future generations is both my responsibility and my privilege.”

Der Hirt auf den Felsen

[I received the following email message from Ms. Valente in March 2016] …thanks for urging me to write this Foreword, for it caused me to bring back to mind so many wonderful memories that I have stored away all these years!