Lehmann in Fanfare Magazine

In the March/April 2025 edition of Fanfare magazine Raymond Beegle opens his review of a recent recording of Brahms songs with: “Lotte Lehmann chose her repertoire by first reading the poetry, feeling a kinship with its sentiment, living with its nuances of rhythm and inflection, and then, only after that, addressing the music of our great song composers. I wager she would not have signed a recording contract stipulating that she sing a certain number of songs, in a certain amount of time to be part of an edition of complete or collected works.”

Leinsdorf

In a December 1993 issue of Musical America Worldwide, Milton Esterow wrote:

In 1934, Toscanini was in Vienna to conduct the Vienna Philharmonic. ‘I was sitting and listening to one of the rehearsals,’ [Erich] Leinsdorf said. ‘One of the officials of the orchestra came into the hall and said they couldn’t find anyone to play Kodaly’s Psalmus Hugaricus on the piano for the old man. I told him I could. Toscanini liked the way I played it.’ For the next three summers Leinsdorf was Toscanini’s assistant in Salzburg. In 1938 Leinsdorf was hired as a conductor at the Metropolitan [Opera]. How did he get the job in New York? [Leinsdorf]: ‘Lotte Lehmann had a lot to do with it. I knew her well in Salzburg. I coached her in some of her roles. But I’ve never quite pinned down who did what. Toscanini? He wasn’t on speaking terms with the Met. The direct line was Lehmann, Edward Johnson and Artur Bodanzky.’

Doctorate

From the June 8, 1951 issue of The Jewish News of Northern California, we have this article on Lehmann, which besides covering many aspects professional and personal, allows us to learn the date of the awarding of one of Lehmann’s Doctorates. Here’s the article:

Mills College Will Honor Mme. Lehmann

An honorary doctor of humanities degree will be awarded Mme. Lotte Lehmann by Mills College at its commencement exercises Sunday, June 10, [1951] at 4 p.m. in the Greek theatre of the Oakland campus. Sen. William F. Knowland and the Rt. Rev. Stephen F. Bayne of Olympia, Wash., also will be awarded degrees at the ceremony, at which 142 degrees, including 39 Masters, will be presented graduates.

Thrilling Voice

Having its roots in the thrilling voice, the superb technique and the consummate interpretive powers of Lehmann, the legend found its farthest-reaching ramifications, its deepest meanings in its projection of the Lehmann personality— soul. Many writers and critics have tried to define it. “When Lotte Lehmann sings,’’ one critic wrote recently, “a door opens into a magic world so simple, so tender, so gentle that only the truly great can open it wide.” The fine intelligence, vitality and restless creative energy that distinguish Lehmann the singer also are responsible for Lehmann the writer, Lehmann the painter and most recently, Lehmann the motion picture actress-singer. The author of numerous articles and essays, Lotte has to her credit a novel “Eternal Fight,” two books of memoirs “Midway in My Song” and “My Many Lives” and “More Than Singing.”

Writes and Paints

Lotte, in addition to possessing a warm, lucid and absorbing style in writing, is an accomplished painter. Although she has studied painting only six years, she has won several distinguished awards and her group of water colors, inspired by Schubert’s songs, were part of her first one woman show in a New York gallery recently. Although on stage Lotte is a statuesque woman of gracious presence and dignified bearing . . . and her smile wins her the unconscious allegiance of her audience . . . off-stage, surrounded by her friends, she sheds this dignity and becomes her real, fun-loving self. Vivacity and a lively interest in people and events are her outstanding social graces. However, she does not care for the more formal aspects of society. She prefers a cozy circle of friends gathered around her coffee table. She delights in long, earnest, and enthusiastic discussions of almost any subject, from the oldest superstition to the newest movie, from music and literature to politics and the weather.

Good Sportsman, too

Swimming and horseback riding have always been her favorite outdoor sports. Swimming, she considers the ideal all-around exercise. “The blood courses more quickly through the veins. One comes out of the water walking on air, invigorated and refreshed.” Possessing a disposition not easily disturbed. Lotte reserves her fire and temperament for the operatic stage and for the concert platform—in short, for her music. She has one phobia. She is allergic to jazz. Not to modern music or to jazz created for its own sake, she hastens to inform you, but to what she considers the current mutilation of the works of the great masters by jazzing them up. “Imagine,” she says, “I go to the movies and they play the Pilgrim’s Chorus from ’Tannhäuser’ in jazz. It is too terrible!” Her greatest joy, Lotte confesses, is to hear the spontaneous and hearty applause of an American audience and to read the plaudits of a free and uncontrolled press. And, as though painting, sketching, writing and gaining world fame as a concert, motion picture and opera star were not enough, Lotte proclaims that even if she could not sing a note she still would have been famous as an actress!

Lehmann Student Kay Griffel Interview

It’s always interesting to read about the career of one of Lehmann’s students who wasn’t as famous as Bumbry or Horne. Griffel’s career was significant (she’s still living) and the interview mentions her work with Lehmann. Read the review.

Canadian Recital

A Lehmann-story from an unknown source:

After Lehmann had sung one of her encores after a February 1946 recital at His Majesty’s Theatre in Montreal, Canada, an audience member called out “Ich liebe dich”. Whether he meant “I love you” as words of affection or whether he was suggesting an encore known by that name, Lehmann and Ulanowsky (the latter without the music!) performed Beethoven’s Zärtliche Liebe (aka Ich liebe dich). BTW the other encores were: Wolf’s Anakreons Grab, and two by Brahms: O liebliche Wangen and Mein Mädel hat einen Rosenmund.

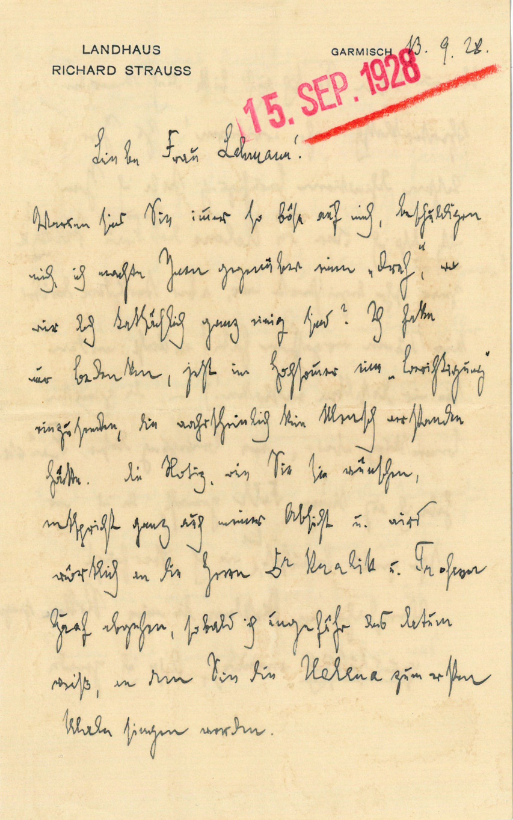

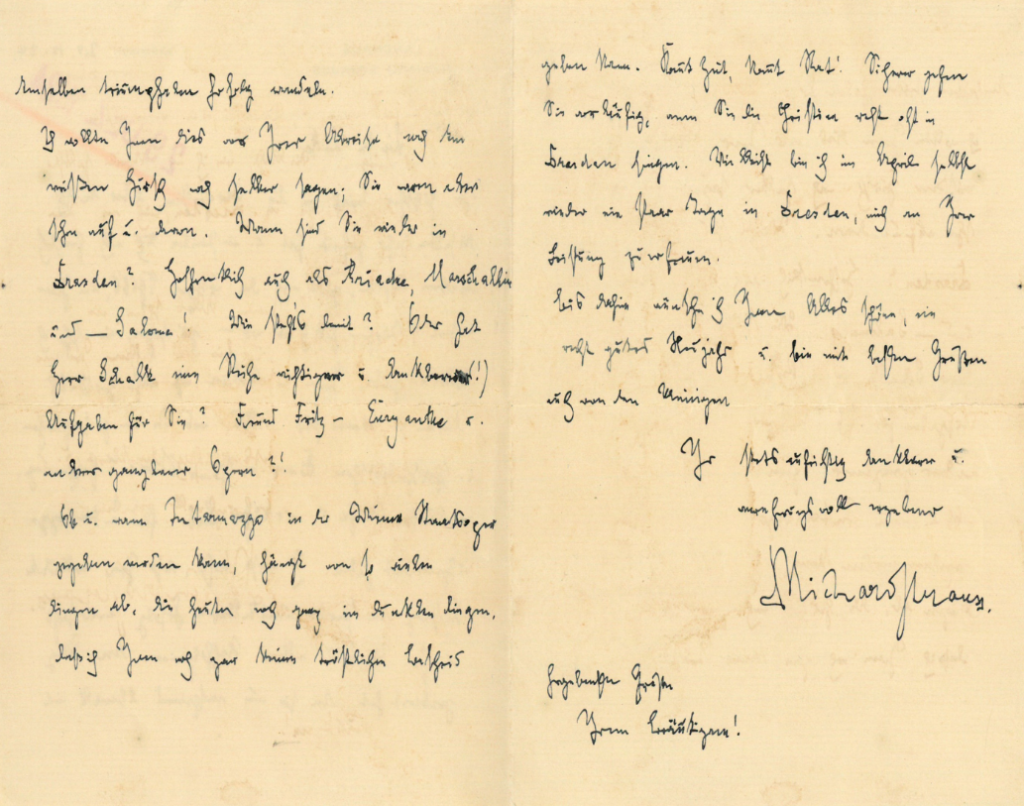

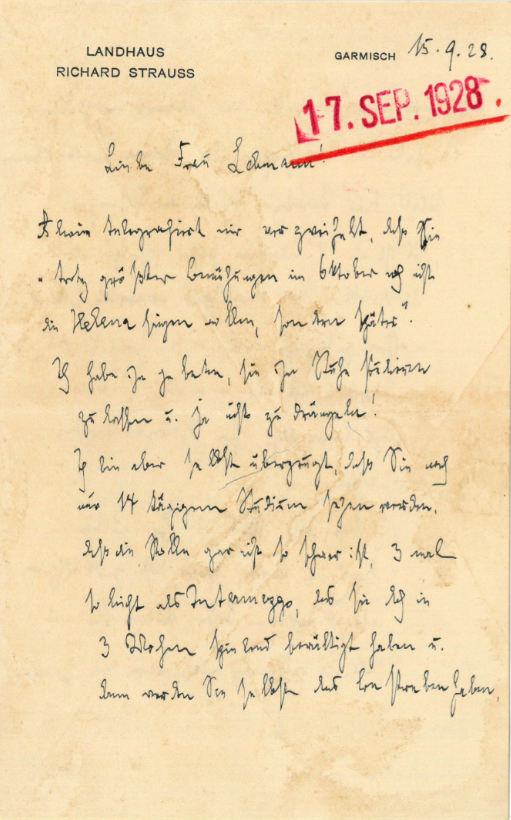

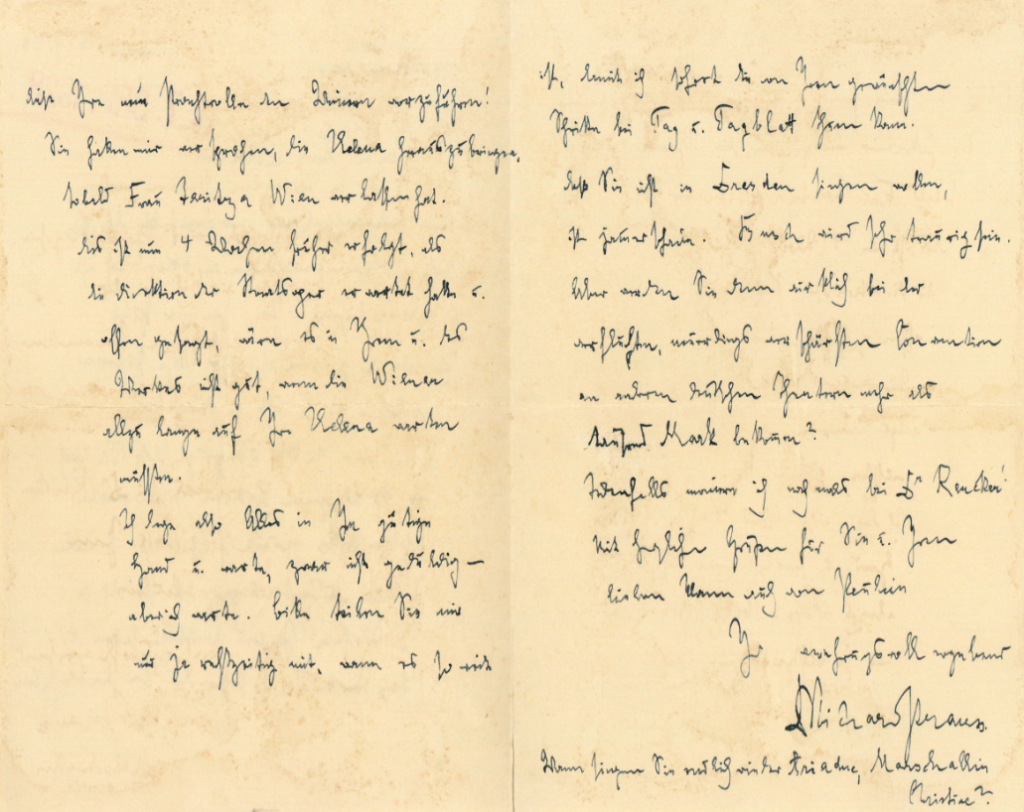

Letters from Richard Strauss

Almost a hundred years after Strauss wrote them, here are two letters that he wrote to Lehmann that were being offered in an auction.

The company that was selling these letters wrote:

To Lotte Lehmann, discussing Intermezzo and Die ägyptische Helena with one of his greatest interpreters. On Christmas Day 1924, Strauss congratulates Lehmann on her performance in Intermezzo, in which she had sung the role of Christine at the premiere on 4 November, and asks when she will return to Dresden, hoping it will be to perform as “Ariadne, the Marschallin and – Salome!”, although perhaps Franz Schalk (at the Vienna Staatsoper) has other plans for her, such as Mascagni’s Freund Fritz or Weber’s Euryanthe; the question of whether Intermezzo will have a production at the Staatsoper (where Strauss had been joint-principal conductor with Schalk until earlier that year) is undecided. – On 13 September 1928 he tries to mollify Lehmann after the scandal over the Die ägyptische Helena (at the premiere on 6 June the Dresden Semperoper had refused to cast Maria Jeritza in the title role, even though Strauss had written it for her, casting Elisabeth Rethberg instead), insisting that “although I was very enthusiastic about Frau Jeritza’s Helena, I still did not shed any tears over it” and apologizing for not having fixed a date for Lehmann’s own performance in the role. – Two days later, he writes again to say that Lehmann’s performance as Helena has been put off from October, and that after two weeks’ study of the role she will realize that “the the role is really not so hard, three times easier than Intermezzo, which you easily mastered in three weeks”, and discussing when the Vienna premiere will take place (after Jeritza has left town), and asking in a postscript “So when will you be singing Ariadne, Marschallin, Christine again?”. – The great soprano had a close association with Strauss’s operas, and sang in the premieres of Ariadne auf Naxos (1916), Die Frau ohne Schatten (1919), and Intermezzo (1924). Her performance as the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier was particularly celebrated.

LL Mentioned

In the February 2025 issue of GBOPERA Lutz Nalepa reviewed the Berlin Opera’s presentation of Die Frau ohne Schatten by Richard Strauss. Here’s how he opened: “The highly-acclaimed Richard Strauss soprano Lotte Lehmann who sang the Dyer’s Wife in the Viennese premiere of Die Frau ohne Schatten in 1919, was later sorry that she had not done more to popularize the challenging work.” [However, in Lehmann’s 1964 book, Singing with Richard Strauss (aka Five Operas and Richard Strauss), she offers a whole chapter of 45 pages on the opera.]

LL Interview

A documentary film Von Reinhardt bis Karajan – 50 Jahre Salzburger Festspiele is available on YouTube. It covers the history of the Salzburg Festival from Reinhardt to Karajan and includes excerpts of an interview that Lehmann gave (in German) in her old age in the garden of her Santa Barbara house. If you want to see only those portions that include Lehmann, go to 23 minutes and then to 29 minutes. There are also brief views of photos of Lehmann as the Marschallin and in a casual shot with Bruno Walter.

Research Paper Errors

Marlina Deasy Hartanto submitted a paper on Lehmann called “Exploring Expressive Lied Performance: Re-enacting Lotte Lehmann’s Pre-World War II Lied Performances,” as a master project for the Royal Conservatoire of The Hague on November 9, 2021. We were able to access it at without charge at ResearchCatalogue.net on June 26, 2023. I have since read one chapter (see below) and have had to correct many errors. So if you plan to read the whole paper, be advised that there are numerous mistakes, misunderstandings, and English-language errors.

You can read this whole paper by going to https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/969662/1183012

CHAPTER III: UNDERSTANDING THE ARTIST AND HER VOCALITY

Lotte Lehmann in Focus

Lehmann is seen by many as a pre-eminent lied singer in the pre-war German style, and as such sets herself apart from post-war singers like Schwartzkopf and Fischer-Dieskau. Her singing influenced/affected musical life note only in Europe, but across the world. Lied singing became her main interest [even] after she retired from the opera stage. Her success in lied singing even surpassed her operatic triumph.

Being a successful singer in lied performance did not bring her into an easier path [before]. Her interest in lied performance until 1920 was not that profound. Here are remarks she made to her brother about lieder:

Many years ago, at a time when the world of opera was my very own, and lieder a rather foreign territory for me, I sang my lieder recitals in blessed innocence. I remember that one day I said to my brother, Fritz Lehmann, “Singing lieder doesn’t make me very happy. They are melodies and any instrument will do them better justice than the human voice.” He answered that in his opinion each Lied has its own story, is created out of a very personal experience. That remark opened a door for me. Slowly I grew into the perception that a Lied, in a subtle way, is born from an experience, from a “story”.1

It took some time for Lehmann to develop herself as a lied singer. She realized that she often sang too robustly and not intimately enough. It was often noted that she sang certain songs such as Der Doppegänger, Erkönig, Ich grolle nicht, Frühlingsnacht, and Winterreise which were considered to be more suitable for a man than for a woman.2 She did not know still that she would become a master of singing whose performances would be loved the world over. “So, in singing Lieder, the word, the poem became the main thing for me, until I – much later – found and captured the balanced interweaving of word and music,” she remarked.3

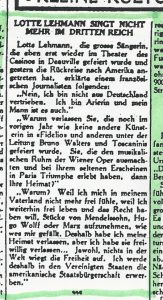

Lehmann’s fanbase grew and became known as “Lehmaniacs”. Her popularity even captured Hitler’s attention. On 19 April 1934, Hermann Göring, Hitler’s Minister of Education invited Lehmann to come to Berlin, offered her the title of Primadona of Germany, as a permanent member of the Berlin Opera. Göring proposed an enormous fee that left Lehmann speechless.4 She was one of a select few musicians who were in direct contact with the Nazi Party.[not true] Although Lehmann was a fearless woman, her charisma also got her in trouble with the Third Reich.

I hate politics. I am an artist, nothing but an artist. I have the marvelous privilege of living in a land where there is only beauty. I like to sing everywhere, in all countries, before all audiences. I know the miraculous power of art to unite people, to lift them above themselves, to let them forget their shabby disputes. In the presence of art, there are no enemies, no borders, no political parties, there are human beings who suffer and look for the light.5

In 1934, German artists were forbidden from participating in the Salzburg Festival.[not true] The Second World War also broke German traditions in music making. However, Lehmann still managed to perform successfully in Salzburg with Arturo Toscanini and Bruno Walter.[and others during the Nazi time] Due to the political situation, she was limited in her ability to perform in different countries in Europe. [not true] Lehmann emigrated to the United States in 1937 where she became a preeminent lied and opera singer.

After Germany surrendered unconditionally in May 1945, World War II in Europe was over. The ravages and devastation were immense. In the book about Lotte Lehmann, A Life in Opera and Song, Beaumont Glass described her situation after the World War II:

Lotte was deeply depressed by conditions in the land of her birth and in Austria, her home for so many wonderful years. That depression naturally took its toll in physical terms. Her nerves were frayed; there were frequent hemorrhages of the vocal cords. Nevertheless, she continued to force herself into concert trim; her art as a lieder singer was deepening every year, and her repertoire was constantly expanding. Now that she had closed the door on her opera career, she gave herself completely to the Lied.6

In 1945, she published her book of More than Singing, a lieder interpretation treatise. This book was made as a guide for young singers to have a deeper understanding of lied singing. She wrote that her fundamental conception was to see lied as more than just melody. She challenged singers to search for the ideas, nuance, pictures, feelings which underlie the songs and to dig into the situation in which the poem was born. Singers, she felt, must understand what kind of drama, dream, and experience inspired the poetic and musical conceptions of a work.7

The farewell concert of Lotte Lehmann in 1951 marked the end of a pre-war German lied performance style generation of singers who knew this older singing style. The style became fossilized in historical recordings when she stepped off stage.8

Winterreise

In the January 2025 issue of the BBC Music Magazine there’s a list of recommended recordings of Schubert’s Winterreise. At the point that Christa Ludwig’s recording is mentioned, the uncredited author writes: “Though Winterreise is evidently written for a woman (with the text’s references to a bride and suchlike), several women singers have found it irresistible, and the results have often been remarkable: if Birgitte Fassbaender’s recording hadn’t been deleted by EMI, it would have been my unquestioned first choice; and Lotte Lehmann is incomparable, as always.

Recording Review Mentions Lehmann

From a November 2024 OperaWire review:

Rachel Fenlon’s Winterreise is quite extraordinary for many reasons. First, Schubert’s famously melancholy cycle was originally written for tenor, and though frequently transcribed for baritonal depths or even bass, its interpretation history remains confined largely to male voices. Secondly, Fenlon achieves a high degree of German Innerlichkeit, that somewhat obscure, culturally rooted feeling of inward expressiveness which so pervaded the recordings of Lotte Lehmann (the first woman to perform all of Winterreise). [perform and record]

Lehmann Centennial Review

Here is a Los Angeles Times review of the 1988 Lehmann Centennial held at UCSB.

Centennial Celebration for a Singing Actress

By MARTIN BERNHEIMER

June 5, 1988 12 AM PT

SANTA BARBARA — Contrary to popular myth, she wasn’t the only great Germanic soprano of her time.

The stately Kirsten Flagstad had a much bigger voice and a better technique. Frida Leider commanded the heroic challenges–Isolde and Brunnhilde–that eluded her. Maria Jeritza was more glamorous, more temperamental. Elisabeth Rethberg mastered the lofty Verdi heroines that she avoided.

Still, Lotte Lehmann was unique.

Tenors loved her. “Che bella magnifica voce!” exclaimed Enrico Caruso, who wanted to sing Don Jose to her Micaela. Leo Slezak said “she possessed our secret weapon–the only one we have: heart.” Lauritz Melchior simply called her “ My Sieglinde.”

Conductors loved her. Otto Klemperer, Franz Schalk, Bruno Walter, Richard Strauss and Hans Knappertsbusch sang her praises lustily, and they represented just a small part of a large chorus. Arturo Toscanini found her so appealing, off stage as well as on, that he permitted her the indulgence of a downward transposition in Fidelio’s “Abscheulicher.”

Composers loved her. Citing her “rare fusion of a soulful voice with excellent articulation of the text with genial force of expression and a lovely stage appearance,” Richard Strauss insisted that she sing the premieres of his revised “Ariadne auf Naxos,” his “Frau ohne Schatten” and “Intermezzo.” He was willing, moreover, to temporarily sanction any liberties she would take with the vocal line.

Puccini felt that she was the first soprano who really could validate his “Suor Angelica.” That she did so in the wrong language was irrelevant.

Audiences adored her, from her debut as a bit player in Hamburg in 1910 to her years as a reigning diva in Vienna to her career as a song specialist throughout America to her extended farewells in Southern California.

A final performance of her signature role, the Marschallin in “Der Rosenkavalier,” took place with the San Francisco Opera in Los Angeles on Nov. 1, 1946. (The Times review, dated Nov. 2, doesn’t even mention the milestone.) Her valedictory recital followed five years later in Pasadena. The masses continued to adore her in old age as she performed–the verb is emphatically accurate–in public master classes.

Even critics adored her, most of the time. A Beckmesser or two may have lamented her tendency to approximate pitches or distort rhythms as she sacrificed precision to passion. Others worried about her top tones in later years, or her eagerness to usurp lieder that tradition had assigned exclusively to male voices. A few iconoclasts groused that she conveyed housewifely decency even when she wanted to be very complex and very grand.

But no one doubted her profound poetic instincts or took her interpretive rapture for granted. No one questioned the radiance of her tone or the generosity of her spirit.

Lehmann was capable of disarmingly candid self-appraisal. Possibly protesting too much, she liked to admit that her technique was somewhat erratic, especially in matters of breath control. Although she enjoyed a splendid success at the Vienna premiere of Puccini’s “Turandot” in 1926, she said she took greater pleasure in the performance of Maria Nemeth, her alternate in the strenuous title role.

Still, she knew her strengths. “I am a person,” she declared, “who cannot do anything without being totally, compulsively devoted to the effort.”

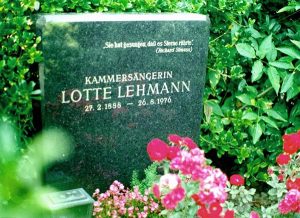

The effort eventually embraced lecturing, writing, painting and stage directing as well as singing. After Lehmann died at her beloved home in Santa Barbara on Aug. 26, 1976, aficionados everywhere continued to worship her. Fanatics with long and/or rose-colored memories dismissed such soprano whippersnappers as Reining, Bampton, Varnay, Schwarzkopf, Della Casa, Grummer, Steber, Crespin, Soderstrom, Rysanek, Jurinac and Altmeyer. “Very nice,” they invariably clucked, “but you didn’t see Lehmann.”

The world at large, however, proved somewhat fickle. Much of the huge but in many ways frustrating Lehmann discography lapsed into library limbo. A new, more inhibited generation of performers and audiences tended to find her art oddly effusive and dangerously old-fashioned. The ranks of the devout began to thin.

Lehmann would have been 100 on Feb. 27, 1988. It was, clearly, time for revival and reappraisal. It was time for a centennial celebration. UC Santa Barbara, which houses the exhaustive Lehmann archives, provided just that last weekend.

For three busy, potentially hypnotic days, the cold little concert hall–it happens to be called Lotte Lehmann Hall–in this mirage of a campus by the sea was warmed with lectures, concerts, multimedia presentations, panel discussions, fanciful seances and fancy tributes. An “official” biography was introduced. Paintings were exhibited. Rare recordings were played. Hyperbole flowed in sincere abundance.

Lehmann’s erstwhile students came to the shrine. Her friends, colleagues and associates came. Her disciples came. Who says nostalgia isn’t what it used to be?

Ironically, the people who didn’t come turned out to be the ones who could have benefited most from the illustrious examples and poignant testimonials. The crowds, though vastly enthusiastic, were disappointingly small and distinctly mature. Despite the scholarly ambiance, one saw few young faces.

After the inaugural ceremonies on Friday, Maurice Abravanel took the podium. Now 85, he offered vivid recollections of his collaborations with Lehmann, as conductor and as administrator at the Music Academy of the West. He spoke with extraordinary warmth of her impetuosity and her flexibility. He invoked the poetic excitement of her creations and confirmed the prosaic insignificance of her miscalculations.

He was the first of many speakers to stress the singer’s concern for the word and its telling inflection. “With Lehmann,” he said, “expression was everything.”

Variations on this reverential theme were immediately provided, via videotape, by Dolores M. Hsu, UCSB music department chairman; Gwendolyn Koldofsky, Lehmann’s longtime accompanist, and Frances Holden, Lehmann’s muse, companion, rock of Gibraltar and personal Brangane.

Beaumont Glass, erstwhile assistant to Lehmann at the Academy and now head of the opera department at the University of Iowa, offered a thoughtful preview of his new biography of the soprano (Capra Press, Santa Barbara: $18.95).

Paradox clouded the picture that night when Carol Neblett, who for a short time had coached repertory with Lehmann, offered a recital in her mentor’s honor. Contrary to the exalted Lehmann tradition, Neblett sang over-familiar music of Schubert, Brahms, Debussy and Strauss with much luminous tone and little interpretive insight. The words counted for little, and the subtleties behind the words counted for less.

Ironically, Neblett’s duochromatic delivery and chronically glamorous image suggested nothing so much as a latter-day incarnation of Lehmann’s arch-rival, Maria Jeritza.

The symposium reached its high point Sunday morning with a brilliant paper presented by Richard Exner of the Santa Barbara faculty. This imposing literary authority chose a subject–the strange but mutually enriching relationship between Richard Strauss and his librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal–that bore only a tangential relationship to Lehmann. However, Exner explored that subject, and its capricious arguments regarding the relative impact of word and music, with probing wit and contextual wisdom.

Edward Downes completed this most stimulating session with personal recollections of the prima donna in Europe. He mentioned that Lehmann claimed to admire Flagstad’s singing but found her Scandinavian colleague cold. He also mentioned, conversely, that the essentially prim and placid Flagstad admired Lehmann’s singing but found that she enacted Sieglinde “as if doing a striptease.”

To belie the notion that Lehmann always had difficulties with her top voice, the visiting musicologist played an early recording of Butterfly’s entrance aria. Lehmann rode the crest of the climax to an effortless, gleaming high D-flat. It elicited a collective gasp.

Betraying his own special fondness for Lehmann, Downes admitted that the heart-bedecked tie around his neck had been an impulsive mid-interview gift from the prima donna some 50 years ago. It elicited wild applause.

The afternoon session found Beaumont Glass returning to recount Lehmann’s concert career. At the end, he played the famous recording of “An die Musik” as sung by the soprano at her final New York recital. Choked with emotion, she was unable to utter the last grateful apostrophe to her art: “Ich danke dir.” Even now, 37 years after the event, this remains a wrenching document of renunciation.

Redundancy began to set in as Alan Rich, music critic of the Herald Examiner, traced the evolution of Lehmann’s art through successive recordings of the same material. One had to admire his sentimental enthusiasm even if one could disagree with his premise–”She became a more conscious singer with age.”

The concert Sunday night, interesting if not entirely successful, was a ghostly experiment devoted to the monumental “Winterreise.” Some 400 slides allowed us to examine Lehmann’s pretty, naive illustrations–in toto and in nervously changing detail–on a big screen. Meanwhile, Lehmann’s isolated recordings of the songs that comprise Schubert’s tragic cycle were pieced together for a less than cumulative sound track. Under these contrived circumstances, the comic-bookish, essentially amateurish paintings somehow managed to overwhelm the pathos of the music and obscure the ardent professionalism of the singing.

On Monday, Gary Hickling, a bassist of the Honolulu Symphony, offered an illuminating, obsessive glimpse into the Lehmann discography. Then the houselights went down and a shadowy, elderly Lehmann appeared in film clips from her famous master classes. She impersonated a melodramatic Ortrud for an innocent student mezzo. With minimal prodding, she enacted the Marschallin’s entire monologue while croaking the vocal line an octave or two below the normal terrain.

She exuded eloquence and savoir-faire. Music and the theater obviously were in her blood. The sound of applause, she often admitted, was irresistible to her. The documents are important.

Still, one must question their educational value. Lehmann reportedly exhorted her students not to copy her. In her classes, however, she seemed to prefer demonstrating to teaching.

Here, she would say, you smile. Here, you take three steps, raise an arm and look upward. . . .

It looked terrific when she did it. It looked silly when those nice, ultra-American kids imitated her.

The symposium closed with seven of Lehmann’s erstwhile students joining in an awe-inspired if not awe-inspiring panel discussion. Significantly, only one of the participants, the soprano Kay Griffel, had gone on from the Lehmann classroom to a reasonably substantial career.

Actually, many singers attended Lehmann’s classes. But none emerged as an artist who could even approach Lehmann’s stature. If Lehmann knew her own secrets, she did not know how to pass them on. [Many successful singers who worked with Lehmann would disagree: Jeannine Altmeyer, Lucine Amara, Karan Armstrong, Judith Beckman(n), Grace Bumbry, William Cochran, Marilyn Horne, Lotfi Mansouri, Mildred Miller, Norman Mittelmann, Thomas Moser, Carol Neblett, Maralin Niska, Harve(y) Presnell, Marcella Reale, and Benita Valente]

The evidence suggests that she was not a great teacher. Nor, for that matter, does she seem to have been a great writer or a great painter. It doesn’t matter.

She was a great singing actress. That is enough.

We can see it clearly now.

Biography in Music: Lehmann

Francis Robinson, with many connections to the Metropolitan Opera recorded a Biography in Music to celebrate Lehmann’s 80th birthday and broadcast it on 2/24/1968.

Here’s background information on Mr. Robinson:

Francis Robinson began his career in the theater as an usher at the Ryman Auditorium while he was studying at Vanderbilt. He received his B.A. from Vanderbilt in 1932 and his M.A. in 1933. He went on to spend more than thirty years at the Metropolitan Opera where he served variously as tour director, assistant manager, press representative, and host of Saturday afternoon broadcasts from the Met.

Robinson began appearing on the popular “Texaco Opera Quiz” in the 1950s, which aired during radio broadcasts of Met performances, but on February 27, 1960, he came into his own on the Metropolitan Opera broadcast with a musical biography of Enrico Caruso. Using his own extensive collection of Caruso recordings and materials, Robinson put together a twenty-minute program honoring the great tenor. It was a huge success, and that broadcast was the impetus for a series by Robinson called “Biographies in Music” that took place during the third intermission of the Met’s Saturday broadcasts. In introducing Robinson and the series, Milton Cross, host of the Metropolitan Opera broadcast, said that the musical biography of Enrico Caruso was “so moving and brought so many requests for more musical biographies that we have persuaded Mr. Robinson to do a series of such broadcasts for us.” In 1978, Robinson became host for the Live from the Met telecast series, continuing to reach out to opera audiences around the country. He wrote program notes for more than 100 RCA Red Seal albums. The Francis Robinson Collection of Theatre, Music and Dance was given to the Vanderbilt Libraries in 1980.

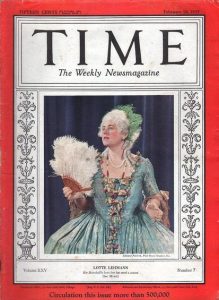

TIME Magazine 1934

Music: I Am Success

In the little German town of Perleberg some 30 years ago a lusty argument went on between a round-faced, pig-tailed girl and her practical, hard-working father. The child was determined to be a singer. The father wanted her to teach school to be sure of getting a pension in her old age. When Lotte Lehmann’s singing days are done she will get a pension from the proud Vienna Opera where she is a Member of Honor. By the time she sailed for Europe this week many a hard-to-please New Yorker was convinced that hers is the most beautiful soprano voice of the day.

In the U. S. this winter Lotte Lehmann has given 22 concerts, made her radio debut as Toscanini’s chosen soloist and sung three times at the Metropolitan Opera House. Her last Metropolitan performance coincided last week with the conclusion of the Wagner Cycle (TIME, Feb. 12). The opera was Die Meistersinger and Eva who has always seemed a dull heroine suddenly bloomed forth as a charming young person, very much in love. Critics who marvel at the warm eloquence of Lotte Lehmann’s singing, the contralto richness that holds to the highest notes, again complained because they had to wait so long to hear her at the Metropolitan. Chicago had her for a few performances in 1931 and 1932. From Vienna, Salzburg, Paris and London have come ecstatic reports of her Leonore in Fidelio, her Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier. New Yorkers who had heard her only in Lieder suddenly wanted to know more about this stately youthful person who could act as well as sing. During her first years in opera her father never let Lotte Lehmann forget that school-teaching would have been easier and safer. She studied in Berlin, got a contract with the Hamburg Opera where for many months she did bit parts, studying the big roles by herself. One day the prima donna who was to sing in Lohengrin suddenly fell ill and Lotte Lehmann took her place. In her fright she forgot all the hidebound traditions, the routine gestures. But she was so young and unaffected, her voice so richly expressive, that the Hamburgers wanted to hear her in other big parts. She was singing Micaela in Carmen one night while the Vienna Opera director sat in the audience. He had come to find a new tenor but next day the tenor was forgotten and Lehmann was shakily signing a contract which she never stopped to read.

In Vienna, her headquarters for 18 years, Lotte Lehmann has sung some 50 roles in German, French, Italian. In Vienna also she became Frau Otto Krause. Her husband, a tall important-looking insurance director, travels with her to the U. S., complains only of her tremendous energy. She will get up at 7 o’clock in the morning no matter how late she goes to bed. Herr Krause speaks little English but when he hears his wife’s praises he taps his big chest and says impressively: “Yes. with her it is all from the heart.”

In New York Lotte Lehmann lives simply at the Essex House facing Central Park. She keeps no maid, shops at Macy’s. There last week she bought coffee and stockings to take home to her friends. Two New York friendships of which she is particularly proud are with Arturo Toscanini and Geraldine Farrar. Toscanini, who has small patience with most singers, goes to all her performances. She did not recognize Farrar when first she saw her in the front row at her last year’s concert. The oldtime singer was listening so intently, so sympathetically that Lehmann found herself addressing every song to her.

Because she does not go in for backstage tantrums or lug around pet jaguars (see p. 32) Lotte Lehmann rarely makes the news columns. She does not advertise her diet which consists mostly of fruit and vegetables, a glass of sherry before she goes on stage. She keeps dogs and cats in her Vienna home but not in her dressing-room. To every performance she takes photographs of her father, mother, grandmother, brother, husband, kisses them all for luck.

Because her singing has such abundant feeling New Yorkers have wondered if she would not make an ideal Isolde, but Lotte Lehmann knows her limitations, says she would be exhausted before the first act was over. She is more conceited about her horseback riding and her writing than about her singing. Traveling from Buffalo to Havana lately she wrote 3,000 words describing her reaction to the country, the Cuban excitement over new President Carlos Mendieta. Her piece was published in the New York Staats-Zeitung.

One of her books. Verse und Prose, has been published in Vienna. Berlin publishers have the first installments of her autobiography but she doubts if it will ever be released. They want her to add chapters on her U. S. triumphs. Says Mme Lehmann: “I would not feel very intelligent to sit down and write over and over again I am success, I am success. I am success.’ ‘

L.A. Times

Lehmann as Angelica

In an extensive July 2024 article for the Australian Book Review on Puccini’s Il Trittico, Michael Halliwell, baritone and scholar, wrote the following: “It was in Vienna, largely due to Lotte Lehmann’s performance in the title role, that Suor Angelica began to attract more success; this was Puccini’s favorite of the three works…”

Celebrating two 1888 birthdays

Lotte Lehmann and Elisabeth Schumann were both born in 1888. Here’s a tribute by the famous music critic Desmond Shawe-Taylor that he wrote for The Musical Times in October 1988.

Jake Heggie on LL

Contemporary opera and art song composer Jake Heggie wrote an extensive review on many recordings for Stereophile magazine called “Singing to the Soul: The Magic of Art Song on Record”. This excerpt refers to Lehmann.

• Brahms: “Die Mainacht” (May Night)—Lotte Lehmann w. orchestra and two with Paul Ulanowsky, piano. Three versions of a great song by one of the most heartfelt German singers of the 20th century. Lehmann, who was Elisabeth Schumann’s contemporary, friend, and once rival, had a one-of-a-kind voice that, despite its flaws—Schumann’s had plenty as well—inspired the likes of Toscanini, Walter, Eric Korngold, and Richard Strauss. “Die Mainacht” finds her at her expressive best, first close to her peak and then as her voice began to age. Lehmann holds nothing back as she expresses the joy, pain, and longing in Brahms’s heart. Once you hear her sing and explore the full range of her artistry, you’ll either dismiss her as “old fashioned” or acknowledge that few singers were/are as naked in their expression, believing in their repertoire, and honest about who they are. Her Brahms, Strauss, Wagner, Korngold, Weber, and more are definitive….

• For “Der Doppelgänger,” Lehmann’s 1941 recording with Ulanowsky, either the live version or even better, the contemporaneous studio recording with Ulanowsky….[are his choice recordings of the Schubert Lied.] [We dedicate a whole page to Lehmann’s Doppelgänger recordings.]

• Robert Schumann: Dichterliebe (A Poet’s Love)—Lehmann and Walter. This beautiful and moving 16-song cycle is such a popular vocal test that in one season, the Bay Area saw performances by four different major baritones. But I learned every note from Lehmann’s famed 1941 recording with Walter at the piano. The pianism is sketchy, but the age and sadness in the voice of a woman—Lehmann—who was forced to leave the Old World only to watch her new house in the hills of Santa Barbara burn to the ground is palpable. As with so much of Lehmann, the performance evokes the words of Richard Strauss: “Her singing moved the stars.”…

Letter to Alma

From PennState Libraries we have the transcription of a letter that Lehmann wrote to Alma Mahler-Werfel. In 1902 Alma married Mahler who died in 1911; in 1915 she married architecht Walter Gropius from whom she divorced in 1920; in 1929 she married author/novelist Franz Werfel, who died in 1945. Lehmann sang at the funeral of Franz Werfel at Pierce Brothers Mortuary, Hollywood, with Bruno Walter, piano; they performed Schubert Lieder. (Werfel died on 26 August 1945; we don’t know if the funeral was held in August or September. The letter below doesn’t seem to be dated.)

Dear Ms. Alma –

blessed with beauty and spirit, they made these gifts the servants of a selfless ambition: to give inspiration to the two great men, who linked their lives to yours and to whom you were a beloved companion until the end. May the memory of this close yesterday ring back to you as a warm melody for many years to come – and may it transfigure and make today and tomorrow happy for you.

Lotte Lehmann

Santa Barbara

The Music Academy of the West

Artificial Intelligence & LL

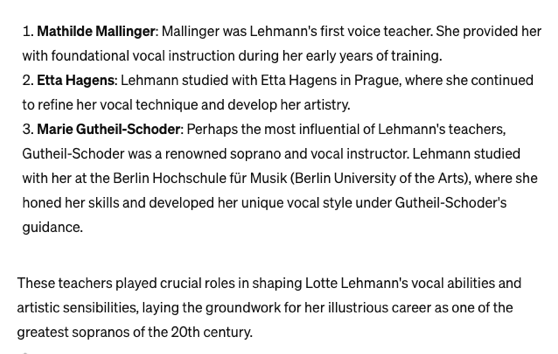

After hearing a lot about AI, it seemed time to test the function of ChatGPT 3.5 on some Lotte Lehmann questions. First, I asked about Lehmann’s students. Here’s the response.

There’s no way to know how AI called Schwarzkopf one of Lehmann’s students. Perhaps because she was the next renouned Marshallin, but nothing else. Grace Bumbry was the one correct listing. As for Risë Stevens, the mixup could have occurred because Stevens sang Octavian to Lehmann’s Marschallin. King’s years were 1925-2005, and though he sang a lot of Wagner and Strauss operas, it was decades after Lehmann’s career. One possible connection is that he studied to change from a baritone to a tenor with Martial Singher, who followed Lehmann teaching at the Music Academy of the West (where King did not study!) Another is that he made his debut as a tenor with Marilyn Horne (an unaknowledged by AI student of Lehmann).

The second question I asked ChatGPT was about Lehmann’s teachers. The first one, Mathilde Mallinger is correct and there were no other teachers of such importance in Lehmann’s life. Of the second listing, Etta Hagens, I can learn nothing. Lehmann never lived or studied in Prague. Marie Gutheil-Schoder (1874-1935) never taught Lehmann. She was already well-known at the Vienna Opera when Lehmann arrived, and Lehmann regarded the elder singer highly. There is no mention of Marie Gutheil-Schoder teaching in Berlin. There is no way I can account for the error of the last two.

The final question I addressed to AI was how to find “reliable” information on Lehmann. The only biography mentioned, Lotte Lehmann: A Life in Opera and Song was written by Beaumont Glass, not Elizabeth L. Norman! I can uncover no connection of Ms. Norman with either Glass or Lehmann. There are two other Lehmann biographies that are available, but not mentioned by ChatGPT.

LL’s Vocal Registers

Conrad Osborne has a blog called Osborne on Opera: A Critical Blog that in 2017 featured a six part series on “Lotte Lehmann and the Bonding of the Registers” that isn’t as technical as it sounds. It’s an interesting read. Another extensive article on Lehmann was inspired by the second set of her recordings by Marston Records.

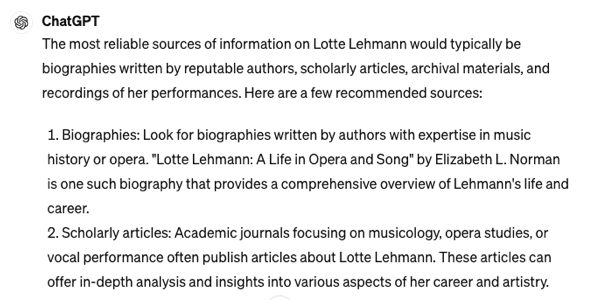

Thomas Mann’s Favorites

You’ll notice that two of Lehmann’s recordings made his “favorites” list. He was also personal friends with both Lehmann and Bruno Walter. Below: a photo of them all together. You can read (and listen to) the list of favorite Lehmann recordings from a vast array of people.

A More Interesting Singer

In the March/April 2024 edition of Fanfare magazine you’ll find a review by Henry Fogel in which he recalls the reason that Flagstad chose a tenor instead of Melchior: “The reason for this was that Flagstad, whose power at the Met was extraordinary, was upset with Melchior after he implied to an interviewer that Lotte Lehmann was a more interesting singer.”

In Comparison

In the 13 March 2024 edition of MusicWeb International, Philip Tsaras reviewed the new CD of Harriet Burns, who along with her pianist, Ian Tindale, were recent winners of the Contemporary Song Prize in the International Vocal Competition at ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Tsaras offers praise for the “sheer beauty of Burn’s voice” and writes: “Comparisons are invidious, but perhaps inevitable, and it was the same story with most of the other songs I sampled in different performances. I would like more characterisation and personality in Die Männer sind méchant and that is what we get from, for instance, Lotte Lehmann…I sampled a few more versions of one of the most well-known songs here Der Jüngling and der Quelle and it was to find that Elisabeth Schumann, Lotte Lehmann,…are all more communicative with the text and much more specific in their response to it.”

As Desdemona in Vienna

The Vienna Opera lists the various sopranos who have sung Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello. Can you guess how many times Lehmann sang the role there? Between 1922 and 1936 Lehmann sang that 16 times! She also sang Desdemona in London’s Covent Garden: 4 times.

Poetry in Translation

In the February 2024 edition of The Offing magazine you can read an English translation of Lehmann’s poems from her 1923 book called Verse in Prosa. The complete poems in that book (in the original German) can be found here.

Mention in Fanfare

In the January/February 2024 issue of Fanfare magazine, Raymond Beegle has problems with the baritone Florian Boesch and writes, “…still one is not so deeply convinced, or drawn into the atmosphere of the texts, as one is when hearing Stéphane Degout sing Stille Tränen in his recent Paris recital, or Lotte Lehmann when she sang Alte Laute in New York at her final concert.” Here’s Lehmann singing Schumann’s Alte Laute from her Farewell Recital in Town Hall in 1951 with Paul Ulanowsky, piano.

Wikipedia Pages Improved

During 2023 my webmeister, Suchi Psarakos, and I have worked to correct, expand, and improve the Lotte Lehmann Wikipedia pages in English, French, Italian, and German. We’ve had the help of Blair Boone-Migura of New York and Damien Top from Paris, (for the French page) and Ulrich Peter of Aachen, Germany for the German page, and Costanza Pernigotti, for the Italian page. We also worked with the Lehmann researcher, Ester González, for the Spanish page. Many thanks to those hard-working writer/translators.

Lohengrin

David Alden, director of the San Francisco Opera’s recent production of Lohengrin, knew the opera intimately—he collects historic recordings, and has at least thirty historic recordings of Lohengrin. His favorites are the Rudolf Kempe recording, and the Metropolitan Opera live recording featuring Lauritz Melchior and Lotte Lehmann conducted by Artur Bodanzky.

Bruno Walter Tempo

In 2024 Dr. Schornstein, who often travelled with Lehmann in her later years, reported to us the following bit of interesting/historical/musical conversation concerning a performance of Fidelio with Bruno Walter: Lehmann said, “I honestly forgot the slow tempo he preferred during the finale duet (and he was furious with me). He muttered, ‘You like it, they like it, but I don’t like it.’”

15 Years of “Lotte Lehmann Woche”

In 2023 the Lotte Lehmann Akademie reported that the Lotte Lehmann Woche (Lotte Lehmann Week) which takes place in Perleberg, Germany (her birthplace), celebrates 15 years. Here’s an article (in German) from the local newspaper, that summarizes Lehmann’s life and tells about the vocal classes and performances.

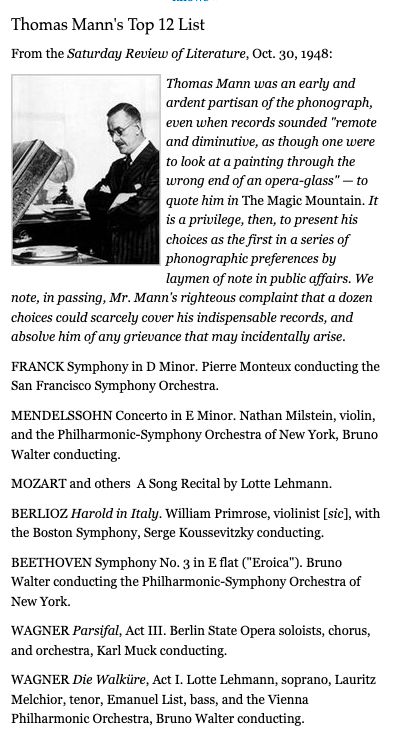

Extra Concert

Thanks to the research of the LAPhil’s archivist, Michelle Beacham, we have an article of 11 May 1947 from the Los Angeles Times providing the information on an unusual Lehmann concert. It was unusual because the Lieder were accompanied by an orchestra and the orchestra was not a famous one.

Current Baritone Compared

In the July/August 2023 issue of Fanfare magazine, Raymond Beegle writes the review for a new recording by baritone Konstantin Ingenpass. The opening paragraph reads: “It is a wonderful thing when an artist with a beautiful voice, a secure technique, intelligence and depth of soul, draws the listener’s attention away from all these virtues, and becomes the very wayfarer, or lover, or holy man he sings about. The young baritone Konstantin Ingenpass has the ability to perform such alchemy…Perhaps not since Lotte Lehman (sic) have we heard this power in such abundance as on this recording.”

Paper on LL’s Early Lieder Performances

Marlina Deasy Hartanto submitted a paper on Lehmann called “Exploring Expressive Lied Performance: Re-enacting Lotte Lehmann’s Pre-World War II Lied Performances,” as a master project for the Royal Conservatoire of The Hague on 9 November 2021. We were able to access it at without charge at ResearchCatalogue.net on 26 June 2023.

You can read this paper by going to https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/969662/1183012

There is no charge for accessing this work. The menu on the exposition page (or first page) appears when hovering with the mouse over the top of the page. Hovering on “content,” you will see the table of contents. Clicking on any of the items will direct you to the other pages.

Hartanto uses as examples of Lehmann‘s singing An die Musik and Ich grolle Nicht and assumes that they were recorded “acoustically” (using a horn instead of a microphone), but in each case, these were “electric” recordings, as were all of Lehmann‘s discs from 1927 on. The great advantage of a modern thesis paper is that the author can provide the very sound she wishes to analyze.

Die Frau ohne Schatten then and now

“Standing in the shadows of love” is the title of Michael Anthonio’s 6 June 2023 review of a new San Francisco Opera production of Die Frau ohne Schatten for the parterre box. He puts the opera into historical perspective and then writes: “In a way, that event probably served as one of the reasons for the lukewarm reception of the premiere in Vienna, despite the participation of two of the greatest singers of the century, Maria Jeritza and Lotte Lehmann, as the Empress and Dyer’s Wife respectively.”

Lehmann in Exile

Ester González presented her work on Lehmann (Speaking of Music: The Transnational Writings of Lotte Lehmann Abroad) at the 2023 German Studies Association Conference in Houston, Texas. She wrote: “This is my first time talking about Lotte Lehmann and I am still learning about her, which so far has been a fascinating adventure. I hope to do her justice, as I really respect her work.”

Lotte Lehmann would be delighted to know about Ester González, the University of Massachusetts Amherst PhD candidate. Originally from Spain, Ester studied classical music at the conservatory in her hometown, but was only vaguely familiar with Lehmann’s name and marvelous voice. She became interested in Lehmann later, as a PhD student in German Cultural Studies. While reading about Lehmann’s encounter with Hermann Göring in her autobiography, Ester was intrigued by Lehmann’s claim that music was international. Ester is fascinated by Lehmann’s notion of her art being different from that of her own country: “My blood is German, my whole being is rooted in the German soil. But my conception of art is different from that of my country.” [From the Postscript of the May, 1938 edition of Lehmann’s memoir, Midway in My Song.]

For her dissertation, Ester is studying the works of German/Austrian artists in U.S. exile during World War II, using five case studies in addition to Lehmann, including Kurt Weill and Stefan Zweig. She is analyzing their relation to/understanding of art and music, through a close, historically contextualized reading of selections from their works. She will then look at how music can be seen both as a national product and universal language.

Ester chose to focus on Lehmann’s novel (Orplid, mein Land, known in English as Midway in My Song) and novelette (On Heaven, Hell, and Hollywood). She was recently at UC Santa Barbara’s Special Collections Lehmann Archive, doing research for her dissertation chapter on Lehmann, and along the way she discovered some wonderful examples of Lehmann’s writing, which she shared with us for this website.

Recently Ester presented her work on Lehmann (Speaking of Music: The Transnational Writings of Lotte Lehmann Abroad) at the 2023 German Studies Association Conference in Houston, Texas. She wrote: “This is my first time talking about Lotte Lehmann and I am still learning about her, which so far has been a fascinating adventure. I hope to do her justice, as I really respect her work.”

Ester expects to defend her dissertation within the next 2–3 years. She hopes to eventually adapt its chapter on Lehmann to present at a future conference.

Met Debut Review

The parterre box writer Windycityoperaman celebrated the 11 January 1934 night that Lehmann made her Metropolitan Opera debut in what was called “the ideal Sieglinde” in Wagner’s Die Walküre with the review written by Leonard Liebling for the New York American:

Previously known here as a finished exponent of German Lieder in recital, Lotte Lehmann made her local operatic debut last evening at the Metropolitan as Sieglinde in “Die Walkuere.” Mme. Lehmann is no newcomer to the lyric stage, for at the Vienna Opera she has long been one of the adornments in Wagnerian and lesser soprano roles. Other European theatres and the late Chicago Civic Opera Company also are acquainted with Mme. Lehmann’s striking gifts in the realm of costumed song.

To tell the story of her achievement last night is to report a complete triumph of a kind rarely won from an audience at a Wagnerian occasion. The delighted auditors vented their feelings in a whirlwind of applause and a massed chorus of cheers. At the end of the first act Mme. Lehmann had half a dozen individual recalls and on every side one heard excited and rapturous comment. The stir made by the artist was in every way justified. Of statuesque figure and attractive features, Mme. Lehmann appealed to the eye as irresistibly as she wooed the ear. She has a full, rich voice, brilliant in the upper range and sensuously tinted in the middle register. It is a lyric-dramatic organ, ideal for the role of Sieglinde, and gives forth power as easily as it sounds the gentler accents.

More expressive, emotional, lovely singing has not been heard from any soprano at the Metropolitan for many a season, and, better still, Mme. Lehmann is musical and stylistic in the highest degree. A true Wagnerian artist whom the most diligent fault-finder would be estopped from faulting. In her acting, Mme. Lehmann interprets the impulsive, romanticist rather than the scheming woman who coldly plots the sleeping potion for her husband. Lissome, clinging, impassioned, here was the ideal Sieglinde to inflame Siegmund and sweep him to heroic deeds.

Two Fanfare Referrances

• Lotte Lehmann’s name appears in the November/December 2022 issue of Fanfare magazine. In the Classical Hall of Fame section Raymond Beegle writes positively about baritone Jochen Kupfer’s recording of Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin and writes “His genius as an actor outdistances every other recorded performance with the exception, perhaps, of Lotte Lehmann’s.

• In the Fanfare magazine for September/October 2022 Henry Fogel writes about a Bruno Walter CD set from Immortal Performances recordings: “The two interviews of Lotte Lehmann recounting what Walter meant to her as a teacher are particularly illuminating.” In that same issue and reviewing the same set, Ken Melzer writes: “The final disc offers a broadcast memorial tribute to Walter by Neville Cardus, as well as interviews with soprano Lotte Lehmann…All of the interviewees have compelling personalities, and are gratifyingly forthcoming….” In a review of a recent release of Wagner’s Die Walküre Act I conducted by Christian Thielemann, Huntley Dent writes, “….Making comparisons with earlier recordings, one can draw a straight line heading downward from the classic Bruno Walter account with the Vienna Philharmonic (1935) to today. An age that saw Lotte Lehmann and Lauritz Melchior in the lead roles seems almost mythical to us now…”

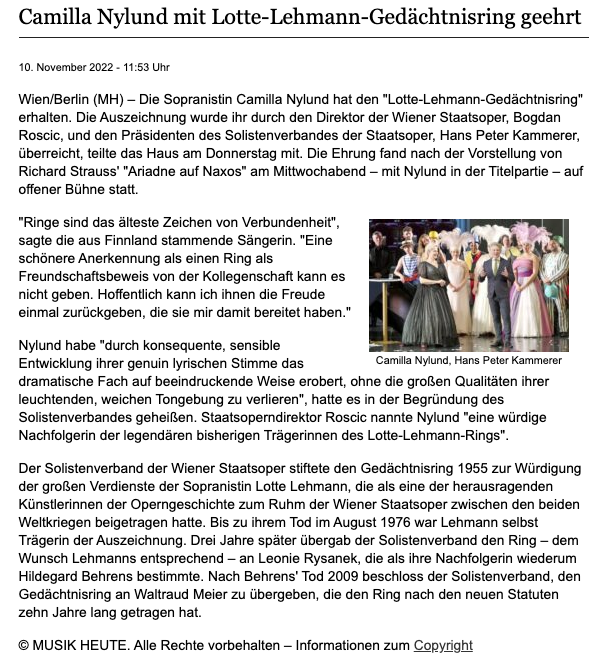

Lehmann Ring Awarded

In November 2022 the soprano Camilla Nylund received the “Lotte Lehmann Memorial Ring”. The award was presented to her by the director of the Vienna State Opera, Bogdan Roscic, and the President of the Soloists’ Association of the State Opera, Hans Peter Kammerer, the house announced on Thursday. The ceremony took place on the open stage after the performance of Richard Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos on Wednesday evening – with Nylund in the title role. “Rings are the oldest sign of connection,” said the Finnish singer. “There can be no nicer recognition than a ring as a token of friendship from colleagues. Hopefully I can give them back the joy they gave me with it.” Nylund has “conquered the dramatic subject in an impressive way through the consistent, sensitive development of her genuinely lyrical voice, without losing the great qualities of her bright, soft sound,” said the soloists’ association. State Opera Director Roscic called Nylund “a worthy successor to the legendary previous holders of the Lotte-Lehmann-Ring”. The Association of Soloists of the Vienna State Opera donated the memorial ring in 1955 to honor the great services of the soprano Lotte Lehmann, who, as one of the outstanding artists in operatic history, had contributed to the fame of the Vienna State Opera between the two world wars. Lehmann herself was the recipient of the award until her death in August 1976. Three years later, the Soloists’ Association handed over the ring – in accordance with Lehmann’s request – to Leonie Rysanek, who in turn appointed Hildegard Behrens as her successor. After Behrens’ death in 2009, the Soloists’ Association decided to give the memorial ring to Waltraud Meier, who, according to the new statutes, wore the ring for ten years.

Judy Sutcliffe on Lehmann

Here is a long article Judy Sutcliffe wrote on Holden, Glass, and the impression that Lehmann‘s singing made on her (Judy). Sutcliffe on Holden et al.

Australian Connection

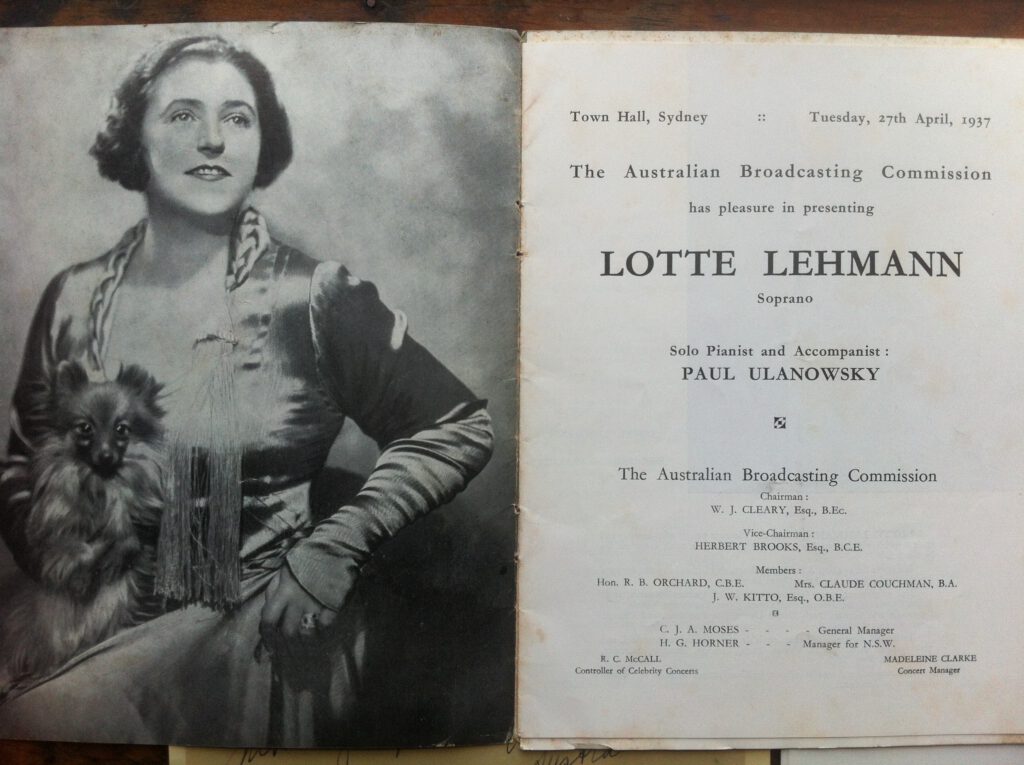

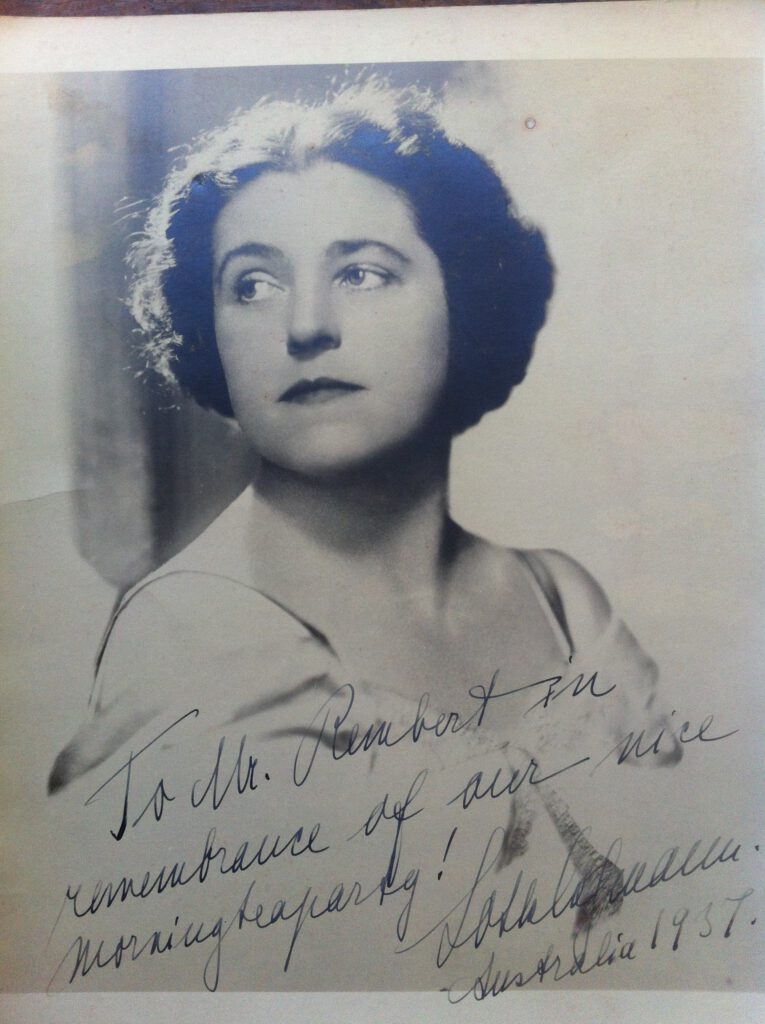

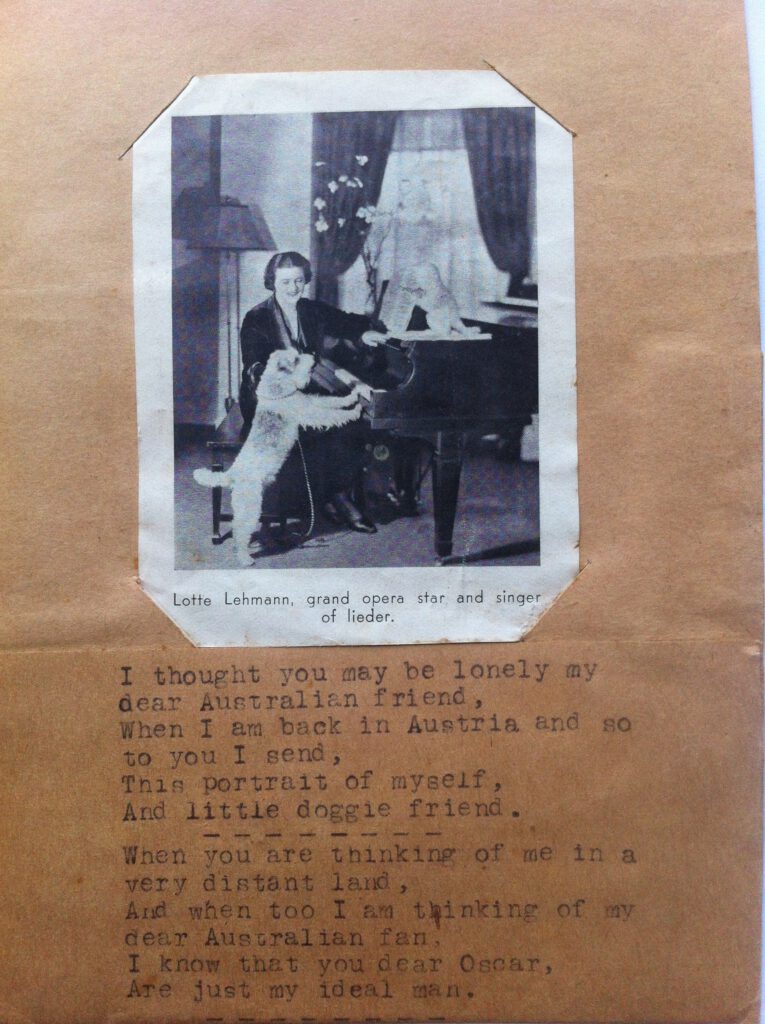

In 2022 we received a letter with attachments from Australia detailing a wonderful Lehmann connection made in 1937.

Dear Gary,

I thought you might be interested in another small episode in the amazing life of Lotte Lehmann to add to your archive.

In 1937 Lotte travelled to Australia with her accompanist Paul Ulanowsky and performed at the Sydney Town Hall (see attached page from the concert program). A man named Charles ‘Oscar’ Rembert was a patron of the classical music scene in Sydney at the time and entertained Lotte when she was visiting Sydney. He clearly made an impression as you can see from these small dedications from Lotte.

Oscar lived in a cottage in the small Blue Mountains town of Wentworth Falls with his younger brother Edward ‘Harry’ Rembert. Oscar had served in the first world war as a gunner, was a bachelor and died in 1958. As the brothers had no close relatives, when Harry died in 1966 they bequeathed their home to my grandmother and her sons (including my father). The Remberts’ had a large collection of 78 classical records including a few of Lotte Lehmann’s recordings. The attached photo and poem were left in the home with all their possessions and unfortunately I don’t have any more information about Lotte Lehmann’s time in Sydney, but I thought you would find it intriguing and I wondered if perhaps Lotte may have spoken with you about her visit to Australia. [Mme Lehmann kept a diary/notebook of her Australian tour and that is available (only in German) on this site.]

Kind regards,

Murray Webber

Met Fees in 1935

Research reveals the payments (per opera performance) that Lehmann received while singing at the Metropolitan Opera. You’ll read the names of other well-known singers of the time, and the amounts they were paid. Remember that this was during the Depression. Also, the dollar in 1935 is worth about $22 as of 2022.

1935: Lehmann: $700

Rethberg: $900

Pons: $1000

Flagstad: $550

Melchior: $900

from 1936-on (the data is a little confusing), Lehmann was paid $750 ($16,500 in 2022 dollars).

Dichterliebe Analyzed

Daniele Palma has written a 10 page work called: “The fine art of lieder singer: Lotte Lehmann recordings of Schumann’s Dichterliebe.” It includes graphs and other technical information on performance techniques, as well as comparisons with other singers. Though written for the University of Florence, the paper is in English.

Marilyn Horne on Lehmann

Jay Nordlinger interviewed Marilyn Horne for the 23 December 2008 National Review, and the subject of Lehmann was discussed. He writes that “Marilyn attended USC, where she was taught by Lotte Lehmann, among others.” Not true. Lehmann never taught at USC, but while Horne was there she attended Lehmann’s master classes at CalTech. He goes on to write “The budding singer also studied with Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West, in Montecito, just south of Santa Barbara [where Horne lives now]….Wanting to know more about Lehmann, I ask, ‘Did she enjoy teaching?’ Horne reflects on this for a moment. Then she says, ‘You know, my sense of it is that she enjoyed being in front of an audience. And out of it came the teaching.’ Lehmann was a real performer, and why not? In any event, ‘I learned a helluva lot from her,’ says Horne.’ Later in the article Nordlinger writes in reference to Christa Ludwig’s fondness for the songs of Hugo Wolf, “Horne sang a lot of Wolf, too. Lehmann stressed Wolf, and Horne learned from Lehmann.”

A “Lehmann” Voice?

In a 15 May 2022 review of Arabella by Strauss, performed at the Zurich Opera, the critic (rml) wrote: The problem is that “tonal glamour” is a requirement for Arabella, and I was curious of how she would fare in a Lotte Lehmann role. Well, it seems I’ll still have to discover, since she was replaced in the last minute by Jacquelyn Wagner. I am not sure that Ms. Wagner has a Lotte Lehmann voice either –

Two Lehmann References

In the May/June 2022 issue of Fanfare, Raymond Beegle reviews a recent release of mezzo soprano Magdalena Kozená singing songs including some Lieder of Brahms. He writes: …“‘My soul has the wings of a nightingale,’ she sings, but does one really believe her? When the words come from the lips of Lotte Lehmann or Christa Ludwig, there is no need to even ask the question. Of course, we believe. But how is it that the same intervals, the same vowels and consonants, rhythms, and tempos of these two past singers, tell us something that Magdalena Kozená does not, cannot tell us? What is it that these earlier singers have that she does not have? This listener guesses that it is wonder, and consequently, sincerity, that goes missing in this singer’s presentation of notes, so adroitly, so carefully cobbled together….”

In the same issue of Fanfare, Beegle is the critic of a recording of Schumann’s Frauenliebe und -leben sung by Alta Marie Boover. Beegle writes: “…When one thinks of the earlier recordings of Theresa Berganza and Lotte Lehmann, one finds Schumann’s Frau diminished and caricaturized here….”

Intermezzo by Strauss

In the 2 May 2022 review of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the Boston Musical Intelligencer, Nicolas Sterner writes in connection with the orchestra’s performances of Four Symphonic Interludes from Intermezzo by Richard Strauss. Of the opera, he writes: “The work is semi-autobiographical in nature, written during a turbulent patch with Strauss’s notoriously high-strung soprano wife, Pauline; when fellow Straussian soprano Lotte Lehmann, who premiered the role of Christine, congratulated Pauline on the ‘marvelous present to you from your husband,’ Pauline retorted, characteristically, ‘I don’t give a damn’…”

Lotte Lehmann-Style

Joseph So wrote in a podcast of 21 April 2022: “For music lovers of a certain age, yours truly included, the classical song recital of yore was typically a rather formal affair steeped in the historical tradition. The singer, conservatively attired in evening wear, stands in front of the curved tail of the concert grand, hands clasped, delivering the songs Lotte Lehmann-style, with sincerity and beauty of tone, but with little fanfare other than the appropriate expressiveness.…”

What she said to her students

In the March/April 2022 issue of Fanfare magazine Raymond Beegle wrote: “…Roderick Williams is a polished singer with a pleasant voice. However, it is overly sweet, overly sentimental, overly ‘sensitive.’ One feels he is trying to convince the listener of his sincerity. ‘I don’t believe you!’ Lotte Lehmann used to say to her students.”

Flagstad on Lehmann

From the November/December 2021 Fanfare magazine: “Faulkner raises the not unlikely possibility that the Norwegian soprano [Kirsten Flagstad] was infuriated at an April 1937 article promoting Lotte Lehmann‘s return to New York, calling her ‘prima donna at the Met.’…It was Lehmann’s publicist who had placed the article, [not verified] and she was also Melchior’s publicist, causing Flagstad to argue with him about it. She retaliated by pressuring the Met’s general manager, Edward Johnson, to hire two additional Heldentenors, Carl Hartmann and Eyvind Laholm, neither of whom was even close to Melchior’s equal. Flagstad also disapproved of the specificity of Lehmann’s acting; when the two met backstage, Flagstad apparently told Lehmann that she did things on stage which only a married woman should do with her husband in the privacy of their bedroom….” –Henry Fogel

Trapp Story

From The Story of the Trapp Family Singers by Maria Augusta Trapp, 1949

On a memorable day in August, 1936, we were sitting together once more behind the screen of pines in our park. It was late in the afternoon, a Saturday. Everybody had stopped working and changed into Sunday clothes. Together we had said the rosary, a ritual which began our Sunday. During the week we had been working on the motet, “Jesu meine Freude” by Bach. Now we sang the movements already memorized, the different verses of the chorale and that wonderful fugue. And then we sang over and over again our newest favorite of which we were especially proud because it was in English: “The Silver Swan” by Orlando Gibbons.

All of a sudden we were interrupted by a strange clapping of hands. A little bewildered, a little embarrassed, we went around the pine screen and met –who could describe our amazement? –the one whom we had so far admired from afar as Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, or as Fidelio–none other than the great Lotte Lehmann.

She had heard that we had let our house in previous summers and wanted to inquire about renting it; and now, just by chance, she had heard us sing, hidden behind the pines. Right there and then she proved how really great she was, for only the great ones can appreciate the achievements of others. With what enthusiasm, her beautiful eyes glowing with warmth, she talked about our “art,” which made us blush and want to kiss her.

“O, children, children,” she exclaimed over and over again; “you must not keep that for yourselves. That precious gift. You must give concerts. You have to share this with the people. You have to go out into the world; you have to go to America!”

Her genuine enthusiasm swept us off our feet. Not that we believed it. Even the poor boy in the fair tale must have a hard time to believe it when he is suddenly told he is a prince.

“Don’t forget,” our illustrious guest continued, “you simply have gold in your throats!”

But the mere thought of having to step on a stage was so frightening that the gold –hidden in the depths of our throats anyhow –was no temptation at all.

“Tomorrow is the festival for group singing. You have to take part in that contest. You simply have to!” She coaxed earnestly and fervently.

Pale with anticipated stage fright, we insisted: “Nnnno…nnnnever!”

My husband was aghast. He loved our music, he adored our singing; but to see his family on a stage –that was simply beyond the comprehension of an Imperial Austrian Navy offer and Baron.

“Madam, that is absolutely out of the question,” he said and meant it.

“Oh, not at all,” Lotte Lehmann said with a twinkle in her eyes. Finally, believe it or not, she had us all convinced. She herself placed a telephone call, which, at this late hour entered us in the contest.

After Lotte Lehmann had left with renewed expressions of her enthusiasm and best wishes for good luck for tomorrow, we woke up. What had we done?

[Of course they won the next day…]

Fanfare Favorite

Fanfare magazine’s Want List 2021 offers their readership the magazine’s critics’ four favorites of the year. Once again, the iBook series Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy was selected. “Once again” because the first volume of the now nine volume document, was chosen in 2016. Here are the words of David Cutler, one of Fanfare magazine’s reviewers: “These new iBooks on German soprano Lotte Lehmann, from expert Gary Hickling, are a very attractive proposition indeed. It is hard not to be overwhelmed by the wealth of material here, covering all aspects of Lehmann’s long life and career. The format is fresh, new, and inventive in covering the career of such an historical singer. What is wonderful is being able to click on the various examples of songs, masterclasses, or performances at the press of a finger! You can hear her as you read!”

Glass’ Up-dated Lehmann Bio

The late Beaumont Glass, who, in 1987 wrote the biography Lotte Lehmann: A Life in Opera & Song, decided to update the book and reinstate material that had been edited out to allow the book to be less than 350 pages. You may now read that entire book (including the published sections and additions) on this site.

Janet Baker on Lehmann

In the late 1950s Janet Baker sang in one of Lehmann’s Wigmore Hall master classes. At the beginning of this interview she discusses her unhappiness with the way Lehmann taught.

Conversations with Lehmann

Sylvia Dreyfus wrote an article called “Notes on Singing: Conversations with Lotte Lehmann.”

Review of Marston Lehmann Box

Here is a personal review of Marston’s latest Lehmann box by Henning Bert-Biel, a German who has lived most of his life in France. He is a Lehmann fan. Unlike the first Lehmann box that Marston’s company released, these CDs are all of electric recordings (using a microphone).

I had time enough to listen to all the 6 CDs of the Lehmann-Box that is really a miracle. The presentation is extraordinary. Good articles and a lot of wonderful photographs, with many detailed explanations. One can’t give a better homage to Lehmann.

This wonderful soprano will be forever in the memory of humanity. It is important to edit CDs like that because our époque easily forgets great things.

I know well the records of Lehmann. When I compare the first discs to the records of 1927-33, I dare say that I love them all. The first group gives all the splendor of a unique voice, the second gives the maturity of a voice with an intelligence of musical expression and pronunciation. The timbre of Lehmann is unique. I like her especially in the German roles (Agathe, Rezia, Elisabeth, Elsa, Eva, Marschallin, Ariadne, Arabella). But that doesn’t mean that the other sides of her repertoire don’t please me. Her Rosalinde is great. Technically Schwarzkopf or Güden are perhaps a little bit more adapted to the great aria of Rosalinde, but none has this natural charm and sensuality of Lehmann. The Italian roles are wonderful. It is regrettable that she didn’t record them in Italian. I was every time astonished that Lehmann didn’t sing more Verdi. I imagine Lehmann as a wonderful Amelia (Ballo in Maschera).

The records of Lieder are sensational. I prefer it when they are accompanied only by piano, but even with the little orchestras Lehmann manages to give an outstanding interpretation. The two Christmas-Songs were for me a revelation. Very often opera singers don’t manage very well to sing those Weihnachtslieder. Lehmann is unbelievable. She sings the songs with simplicity and reveals all the charm, all the magic of those melodies. It sends me back to my childhood and I had a great emotion. It is one of the great marks of Lehmann –this simplicity which in fact is not simplicity. There is no sophistication like Schwarzkopf, but it touches me more. (In spite of that Schwarzkopf is with Grümmer one of my darlings).

The Marschallin of Lehmann is a miracle. She is a woman who knows love, who is sensual and at the same time sensible, ironic, with a good heart and a good sense of reality. Her monolog from the first act is the best interpretation I know.

For me there is another role I cherish about all: Sieglinde. The records of acts 1 and 2 with Walter are monuments. Often I dream that –without Hitler and the Third Reich– they would have been a complete record of Die Walküre with my dream-cast: Lehmann, Melchior, Schorr, List, Leisner (or Branzell) and my beloved Frida Leider.

There are yet so many things to say: The “Wiegenlied” of Strauss, “Der Nussbaum” of Schuhmann, and, and, and…. It’s a pity that “Der Erlkönig” should have sung so quickly (even like this– Lehmann managed it well)…

The songs of her era are interpreted with a lot of charm. I understand that people loved those records. Unterhaltungsmusik (light music) is very difficult to interpret. Many singers do too much; Lehmann or Tauber do just what is necessary for those songs.

I could speak hours and hours about Lehmann and for sure I will read once more her autobiography and the other books I own: My Many Lives and More than Singing. The book by Wessling is interesting, but I prefer the other books. [Wessling’s books on Lehmann are filled with errors.]

Gary, you have accomplished a great thing. All my congratulations!!! If there is a life after the dead (I don’t believe it) Lehmann will be happy about this wonderful edition.

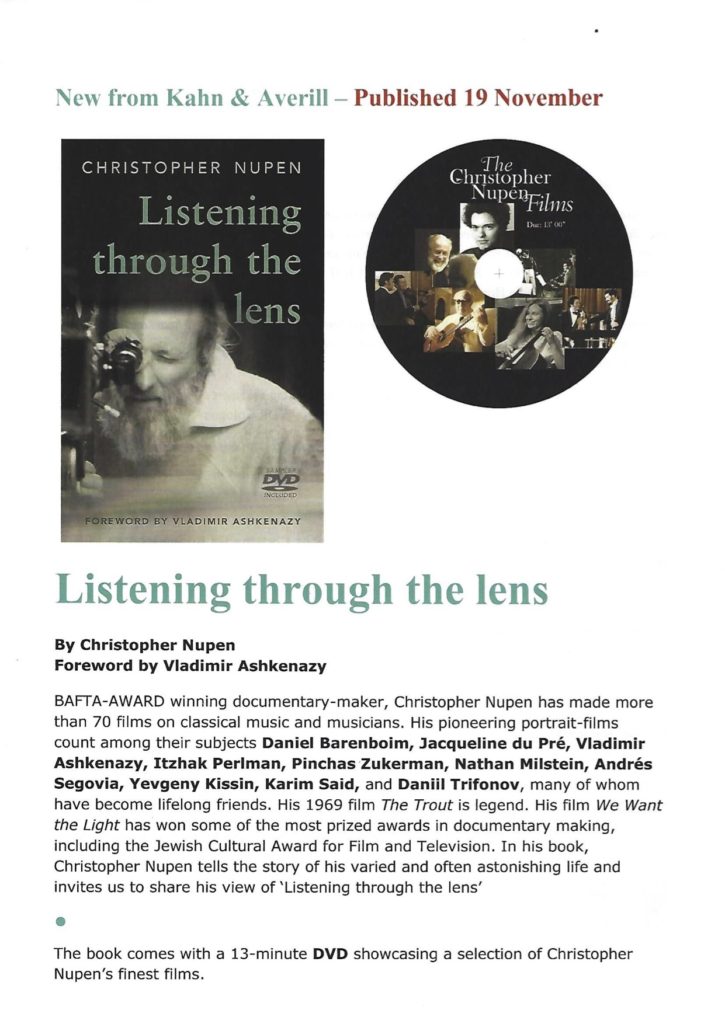

Listening through the Lens by Christopher Nupen

Christopher Nupen, best known for his many videos of classical musicians at work, has written a book: Listening Through the Lens. Its longest chapter is all about meeting Lotte Lehmann in 1955 as a 19 year old. It was she who influenced him in the direction of the arts when he was still a young man. The book is available at Amazon.

Mentioned in Fanfare Review

In the November/December 2019 issue of Fanfare magazine Raymond Beegle reviews a new art song CD of baritone Stéphane Degout and makes several complimentary references to Lehmann. “Like Dmitri Hvorostovsky and Lotte Lehmann, this French baritone found in the songs he chose to sing both words and music that were already in his heart, and that he seems ineluctably compelled to express.…” [Beegle refers to the fact that this is a live recording which adds to its intensity. He then writes:] “It brings to mind Lehmann’s last recital [actually there were a handful that followed], and though Degout is far from the end of his career, his artistry is undeniably equal to hers.…[T]he artists seem to say, ‘Here I am, why shouldn’t I tell you the truth?’ and in each case, the audience members, unified by what was given them, falls into rapt silence, as well they should. What they were hearing were performances of a lifetime.…[Toward the end of the article Beegle expresses his negative reaction to the sound engineering of Degout’s performance, writing…] that makes it considerably less satisfactory than the sound of Lehmann’s 1951 recording.”

Greenberg on Lehmann

On his own RG MUSIC blog of 26 August 2019, Robert Greenberg posted the following article remembering the anniversary of Lehmann’s death:

“She had only to walk on stage to reduce the audience to a melting blob”

On August 26, 1976 – 43 years ago today – the German-born soprano, opera star, lieder singer, movie actress, internationally renowned teacher, music historian and author, published poet, painter and illustrator Lotte Lehmann died in Santa Barbara, California at the age of 88.

In 2004 and 2005, I had the honor of speaking at The Music Academy of the West in Montecito, California, just east of Santa Barbara. The Academy, which was founded in 1947, is one of the great summer music conservatories and festivals in the world. It is also among the most beautiful music facilities anywhere. Perched on over ten acres of beachfront property in the beyond-toney enclave of Montecito, the Academy occupies the former site of the Santa Barbara Country Club. (For our information, along with The Music Academy of the West, other residents of Montecito include Drew Barrymore, Patrick Stewart, Rob Lowe, Al Gore, Oprah Winfrey, Jeff Bridges, Gwynwth Paltrow, and Kirk Douglas. The median price for a house there is a cool four million dollars. Heaven knows how much those ten-plus acres on which the Music Academy sits are now worth!)

My presentations at the Academy took place in the main concert hall, a 300-seat theater called Hahn Hall, and the post-lecture receptions were held in a magnificent, Mediterranean Revival-styled room called Lehmann Hall. I inquired as to the name of the room and was told that it was named for one of the principal founders of the music academy, the soprano Lotte Lehmann. My brain preceded to short-circuit in a manner unusual then but rather more often today, and I responded on the lines of, “Wow. A performance space named for Rosa Klebb!” (“Rosa Klebb” was the SPECTRE agent in the second James Bond film From Russia With Love, a Soviet bloc harridan who killed her victims with a poisoned blade that would emerge from the toe of her right shoe. She was played by the Vienna-born Tony Award-winning singer and actress Lotte Lenya. Lenya rose to fame playing Jenny in the original Berlin production of Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, with music composed by her husband, Kurt Weill.)

With great tact, the lovely lady with whom I was talking gently observed that the room in which we were standing was named for Lotte Lehmann, and not, marvelous though she was as Agent Klebb, Lotte Lenya.

Duh.

The founding mothers and fathers of the Music Academy of the West were an impressive bunch, and include along with Lehmann the conductor Otto Klemperer, the violinist Roman Totenberg, the pianist and harpsichordist Rosalyn Tureck, the operatic baritone John Charles Thomas, and the composers Ernest Bloch, Darius Milhaud, Roy Harris, and Arnold Schoenberg (Schoenberg was the Academy’s first composer in residence). Impressive, yes, though not a one of them has a hall named after him or her except Lehmann. That’s because Lehmann was instrumental (no pun intended) in the founding of the Academy; she was a resident of Santa Barbara and after her retirement from the stage in 1951 she taught there for many years. How this German-born diva got to Santa Barbara, and what she accomplished along the way, should be an inspiration for all of us.

She was born on February 27, 1888 in Perleberg, in the northeastern German state of Brandenburg, midway between Berlin and Hamburg. Trained in Berlin, she made her operatic debut in Hamburg in 1910, at the age of 22. In 1916 she joined the company of the Vienna Court Opera (later the Vienna State Opera), where she quickly established herself as one of the premiere singers of her generation. She sang everything: Gluck, Mozart, Beethoven, Weber, Meyerbeer, Offenbach, Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, Bizet, Gounod, Massenet, Puccini, Mascagni, Richard Strauss, Korngold; the list goes on; I shall not. She sang everywhere and with everyone; such was her fame (and the affection with which she was held) that she appeared on the cover of Time Magazine on February 15, 1935.

Lehmann was not just a great singer but a great actress as well, someone who appears to have been universally admired by her peers (no small thing for an operatic diva). When Enrico Caruso heard her sing for the first time, he embraced her and delivered what was, for him, the highest possible compliment:

“Ah, brava, brava! Che bella magnifica voce! Una voce Italiana!” (“Ah, wonderful, wonderful! What a beautiful, magnificent voice. An Italian voice!”)

Lotte Lehmann was Richard Strauss’ favorite soprano, hands down. Her most famous Strauss role was the world-weary Marschallin from Der Rosenkavalier. Of Lehmann’s portrayal of the Marschallin, Harold Schonberg – the often-curmudgeonly music critic of The New York Times – wrote:

“Talking about it, strong men snuffle and break into tears. They discuss her with the reverence of a legal mind talking about Justice [Oliver Wendell] Holmes, or a baseball connoisseur analyzing [Rogers] Hornsby’s form at the plate, or the old?timer who remembers Toscanini’s Wagner at the Metropolitan Opera. In short, she was The One: unique, irreplaceable, the standard to which all must aspire. . . She generated love, [and] had only to walk on stage to reduce the audience to a melting blob.”

The American journalist and novelist Vincent Sheean was haunted by Madame Lehmann: