Rosenkavalier 1939 Improved

One of the other Lehmann-related sources has been Richard Caniell of Canada’s Immortal Performances. First, he completely re-worked the 1939 broadcast from the Met, of Rosenkavalier. This was an important performance because it includes a lot of material missing from the HMV recording of 1933. The Met performance has a good cast, including the young Risë Stevens, as Octavian. To me, the orchestra portions still sound boxy, but when Lehmann sings, it’s quite natural with plenty of detail. Lehmann’s diction is apparent, as is her complete command of the role. It’s worth the price just to hear the Marschallin sections. By the way, there are extensive “liner” notes with unusual photos, as well as two interviews (in English) with Lehmann and non-Lehmann Act III recordings from 1928. I was in email touch with Richard Caniell and in a P.S., Richard writes: “Immortal Performances was also the source for the Naxos release in 1998 when that company formed its Historical label around our work. Their issue of it was disastrously denigrated in its sound and this was one, of many such occurances, that led us to resign from the project. Anyone who has the Naxos set deserves apologies. I am glad, at last, to be finally associated with something listenable of this broadcast.”

LOHENGRIN 1935

There’s a sort of “second” take on the 1935 Lohengrin with Lehmann, Melchior, Lawrence, Schorr, List, et al, from Immortal Performances. Better sources and, of course the meticulous restoration work of Richard Caniell, make this recording one to really enjoy. Some of the problems associated with such private recordings still persist, but there is MUCH to appreciate. This release is, as the company states, “superior sound to all previously released CD albums by various labels, though it still is afflicted with the compressed 1935 transmission characteristics. Our restoration is taken from the original transcription, with broadcast commentary and curtain calls, and offers a booklet containing extensive articles about the performance, singers and composer, together with rare photos.” Lehmann never disappoints. She sounds young and innocent (she was 47 years old at the time!) in her two major arias that occur in the first act. And Melchior can sing sweetly as well as fervently. The surprise for me was the strong acting/singing of Marjorie Lawrence as Ortrud.

MUSIC & ARTS BOX

The 4 CD set of rare Lotte Lehmann recordings (with a 5th CD ROM containing notes, texts, and translations) is available for purchase at Music & Arts. It represents almost three years of research, editing and finally producing. (Full disclosure: I am the producer). Some background: In July 2013 I finished working with Lani Spahr, who was the restoration engineer for this Music & Arts Lehmann CD set that features her live performances and other rarities. It was amazing to listen to the improvements he was able to make on some of the noisy radio broadcasts of the 1930s and 40s. And of course, Lehmann never fails! I do believe that the audience brought out even more intensity in her interpretations. That implies that some of these tracks contain material that Lehmann recorded in the studio, which is true. But there is also a huge amount of music that she did not record. And a total of 21 items never heard before in any format! In November 2013 I had the pleasure of working with the graphic designer, Mark Hamilton Evans. The set is called Lotte Lehmann: A 125th Birthday Tribute. Besides the four CDs of Lehmann’s singing, there’s a fifth CD that holds the liner notes, which includes the article “The Life and Art of Lotte Lehmann” by the late Beaumont Glass. There are also many photos, my short article, as well as the texts and translations, all total: 111 pages!

LOTTE LEHMANN: A 125th Birthday Tribute • Lotte Lehmann (sop); various pianists; various conductors; various orchestras • MUSIC & ARTS 1279 (4 CDs + CD ROM: 295:05) Producer Gary Hickling, a friend of Lehmann’s, the creator and maintainer of her discography, and a generous enthusiast of her art, approached Music & Arts to issue 19 previously unreleased recordings of the singer. This is the result. In all honesty, there’s nothing revelatory about the fresh material, here. The unissued live selections, in particular those recorded at a Los Angeles school auditorium in 1949 and parts of Town Hall recitals from 1943 and 1946, are a delight to hear, but not mandatory in the sense that they shed new light on her gifts, expertise, or repertoire. Indeed, two of the 19 are short speaking excerpts by Lehmann and Bruno Walter, while a third has Lehmann reading a poem of hers. But for the completist it provides yet further examples of the soprano’s intensity, radiant voice, and exceptional interpretative skill. And of course, by being extended to four very full discs, it not unintentionally furnishes an excellent entry point for the new listener curious about the singer.

The emphasis is not on opera, though we do get one selection a piece from Der Rosenkavalier, Ariadne auf Naxos, Lohengrin, and Tosca. (Hickling’s web site is the place to go to sample much more opera, from a rapturous “Alles pflegt schon längst der Ruh’” [Der Freischütz] of 1929, to a delightfully flirtatiously “Mein Herr, was dächten Sie von mir” [Die Fledermaus] of 1931.) Instead, there’s a great deal of Wolf, Schubert, Brahms, and a fair amount of Beethoven and Mendelssohn. Given that there’s so much of Lehmann available, Hickling was able to focus on some of the very best: “Der Doppelgänger,” “Wenn ich in deine Augen seh’,” a remarkable “Der Wanderer,” and Mendelssohn’s “Schilflied” in a performance that demonstrates a careful expending of breath to create a seamless legato—not a usual feature of this passionately expressive artist. We also get some choice rarities, including a test pressing of Beethoven’s “Wonne der Wehmut” from 1941 that was never released on 78s, a “Vissi d’arte” in Italian from a 1938 radio broadcast, and an early 19th-century nationalistic song, Groos’s “Freihart die ich meine,” which the Thousand Year Reich revived in an entirely new context.

Both Music & Arts and Hickling deserve praise for their willingness to place texts and translations on a fifth disc as part of a PDF file. This saves on the cost of what would be a fat and rather awkwardly managed booklet, as well as allowing the producer the luxury of adding numerous Lehmann images and a plethora of personal observations. Curiously, the lengthy biography preserves a myth about Lehmann’s interaction with Goering started by the singer herself, and corrected in an essay on Hickling’s Lotte Lehmann League web site. The late author of the notes may not have been aware of the detective work that assembled an accurate picture of the events, but those errors of fact could have been reasonably edited out without affecting the considerable quality of the rest of the material.

It is not relevant to the wealth of musical content on this set, however, or indeed to anything in Lehmann’s art and her legacy of recordings, students, and her extremely insightful book, More Than Singing: The Interpretation of Songs. Both Hickling and Music & Arts deserve praise for this excellent set, in very good sound, that is clearly a labor of love. Enthusiastically recommended.

Barry Brenesal

Acoustics in Great Sound

Ward Marston has made all of Lehmann’s Acoustics available in great sound!

You can now obtain technologically advanced sound for the acoustic recordings of Lotte Lehmann (plus some wonderful electrics) from Marston Records. Here’s what Ward Marston wrote:

Lotte Lehmann’s acoustic Odeon discs were issued only in double-faced format, but pressings dating from the late 1920s sound far quieter than the earlier pressings from 1924–1926. We have made every effort to locate late pressings, but they are scarce and, in some cases, we had to use earlier, slightly noisier pressings. For the Odeon recordings especially, the choice of stylus was critical in bringing Lehmann’s voice into focus. In remastering all of the discs, obtrusive clicks, pops, and undesirable noises have been eliminated, and we have made an attempt to remove the harshness caused by horn resonance. The electric recordings chosen for the appendix are all available in beautiful, quiet copies with almost no restoration necessary. We hope that interest in this set will permit us to continue the Lotte Lehmann series with a second volume of her complete electric Odeon recordings.

Lotte Lehmann is today revered for her stellar portrayals of Sieglinde and the Marschallin with commercial recordings and Metropolitan Opera broadcasts giving testament to her in those roles. These highly regarded historic documents have been continuously available together with her no less admired performances of lieder. But most of the recordings now available of this great singer were made during the second half of her forty-year career, by which time she was no longer in her absolute vocal prime. Lehmann is sometimes now remembered as a consummate interpreter and musician, but one with a less than perfect vocal technique. Such judgments are incorrect: In her early recordings we can discover the ease and beauty of her vocal production, her voice fresh and youthful. Lehmann’s earliest records also give us a better idea of her extensive repertoire during the first half of her career. As noted in Dr. Jacobson’s essay, Lehmann sang a large range of roles during her years in Hamburg and Cologne. We are fortunate to get a glimpse of those portrayals through her acoustic recordings, made for Pathé, German Grammophon, and Odeon, between 1914 and 1926.

Lehmann’s first records were made for Pathé—just two sides recorded in 1914. In a hand-written letter from Lehmann to the Pathé administration in February 1915, she confirmed the extension of her contract until February 1916, also requesting payment of 400 Goldmarks. If Lehmann made any additional Pathé records, none were released. In fact, more than three years would pass before Lehmann would again make records. This lone Pathé disc is surely one of the most elusive of all records; in my forty years of collecting, I have never seen a copy offered for sale. We are grateful to Christian Zwarg for making a transfer of this great rarity available for this compilation.

With the outbreak of war in 1914 came a huge upheaval in the record industry in Germany. Relations between the German branch of the Gramophone Company Ltd. and the parent company in London ceased, but the German company continued to make records using the Gramophone Company name. During the first months of 1917, however, the company officially severed all connection to the Gramophone Company, reconstituting itself as the Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft. The new company began recording operations in September 1917 with Lotte Lehmann as one of their first artists. DGG also claimed the right to continue selling any Gramophone Company recordings made before the separation. In 1917, DGG began assigning new numbers to each disc, not only to their newly-produced discs, but also to any earlier Gramophone Company discs. This is why one finds Deutsche Grammophon pressings of records of artists such as Melba, Battistini, and Chaliapin with newly assigned numbers. To make matters more confusing, DGG continued using the old Gramophone Company catalog number system, printing these numbers on the record labels together with their new order numbers. Sometime in 1920, however, they stopped using the old catalog numbers, replacing them with new numbers that began with a letter prefix that denoted the city of location. Therefore, Lehmann’s later DGG discs all bear catalog numbers that begin with the letter B for Berlin. For this compilation, we have listed three numbers for each of Lehmann’s DGG recordings: first, the matrix number is given in parentheses; next is given the DGG order number followed by the company’s internal catalog number in brackets. The first three DGG sessions use the old Gramophone Company catalog numbers, while the fourth, fifth, and sixth sessions use the new DGG numbers.

Many of Lotte Lehmann’s DGG records were issued as single-faced discs, but by the early 1920s, all of her forty-six issued acoustic DGG records were coupled on double-faced discs with new order numbers. These later pressings are preferable because of their quieter background noise. For this compilation all transfers were made from such late pressings.

Electrics by Marston

Lotte Lehmann (1888–1976) was a lyric soprano with a beautiful, rich voice, combined with impeccable musicianship and an innate skill for poetry and storytelling. This six-CD set presents Lehmann’s complete electrical recordings for the Odeon label, all made in Berlin between 1927 and 1933. Lehmann embraced and took full advantage of the new medium of electrical recording while still in her vocal prime. Remembered especially for her portrayals of Wagner and Strauss roles and as a consummate interpreter of German Lieder, her Odeon electrical recordings do not disappoint. Here, Lehmann expands her more famous repertoire to include selections from French and Italian opera to operetta, popular favorites of the time, and some lovely hymns and chorales accompanied by organ. This collection offers selections from Wagner’s Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, Die Walküre, and Lehmann’s only recording of Isolde’s Liebestod. Selections from Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos and Arabella may also be enjoyed. Many gems are included on this set, including: “Leise, leise” from Der Freischütz; “Komm’ Hoffnung” from Fidelio; “Porgi amor” from Le nozze di Figaro; “Kennst du das Land” from Mignon; and Rosalinde’s two songs from Die Fledermaus. There is also a substantial selection of Lieder by Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, and Strauss. The recordings have all been meticulously remastered from original pressings, adding luster to Lehmann’s incomparable singing. The set is completed by a substantial booklet containing an abundance of photos, a biographical overview by Dr. Daniel Jacobson, essays on the recordings by Michael Aspinall and Gary Hickling, and a technical note by Ward Marston.

Here is a personal review of Marston’s latest Lehmann box by Henning Bert-Biel, a German who has lived most of his life in France.

I had time enough to listen to all the 6 CDs of the Lehmann-Box that is really a miracle. The presentation is extraordinary. Good articles and a lot of wonderful photographs, with many detailed explanations. One can’t give a better homage to Lehmann.

This wonderful soprano will be forever in the memory of humanity. It is important to edit CDs like that because our époque easily forgets great things.

I know well the records of Lehmann. When I compare the first discs to the records of 1927-33, I dare say that I love them all. The first group gives all the splendor of a unique voice, the second gives the maturity of a voice with an intelligence of musical expression and pronunciation. The timbre of Lehmann is unique. I like her especially in the German roles (Agathe, Rezia, Elisabeth, Elsa, Eva, Marschallin, Ariadne, Arabella). But that doesn’t mean that the other sides of her repertoire don’t please me. Her Rosalinde is great. Technically Schwarzkopf or Güden are perhaps a little bit more adapted to the great aria of Rosalinde, but none has this natural charm and sensuality of Lehmann. The Italian roles are wonderful. It is regrettable that she didn’t record them in Italian. I was every time astonished that Lehmann didn’t sing more Verdi. I imagine Lehmann as a wonderful Amelia (Ballo in Maschera).

The records of Lieder are sensational. I prefer it when they are accompanied only by piano, but even with the little orchestras Lehmann manages to give an outstanding interpretation. The two Christmas-Songs were for me a revelation. Very often opera singers don’t manage very well to sing those Weihnachtslieder. Lehmann is unbelievable. She sings the songs with simplicity and reveals all the charm, all the magic of those melodies. It sends me back to my childhood and I had a great emotion. It is one of the great marks of Lehmann –this simplicity which in fact is not simplicity. There is no sophistication like Schwarzkopf, but it touches me more. (In spite of that Schwarzkopf is with Grümmer one of my darlings).

The Marschallin of Lehmann is a miracle. She is a woman who knows love, who is sensual and at the same time sensible, ironic, with a good heart and a good sense of reality. Her monolog from the first act is the best interpretation I know.

For me there is another role I cherish about all: Sieglinde. The records of acts 1 and 2 with Walter are monuments. Often I dream that –without Hitler and the Third Reich– they would have been a complete record of Die Walküre with my dream-cast: Lehmann, Melchior, Schorr, List, Leisner (or Branzell) and my beloved Frida Leider.

There are yet so many things to say: The “Wiegenlied” of Strauss, “Der Nussbaum” of Schuhmann, and, and, and…. It’s a pity that “Der Erlkönig” should have sung so quickly (even like this– Lehmann managed it well)…

The songs of her era are interpreted with a lot of charm. I understand that people loved those records. Unterhaltungsmusik (light music) is very difficult to interpret. Many singers do too much; Lehmann or Tauber do just what is necessary for those songs.

I could speak hours and hours about Lehmann and for sure I will read once more her autobiography and the other books I own: My Many Lives and More than Singing. The book by Wessling is interesting, but I prefer the other books. [Wessling’s books on Lehmann are filled with errors.]

Gary, you have accomplished a great thing. All my congratulations!!! If there is a life after the dead (I don’t believe it) Lehmann will be happy about this wonderful edition.

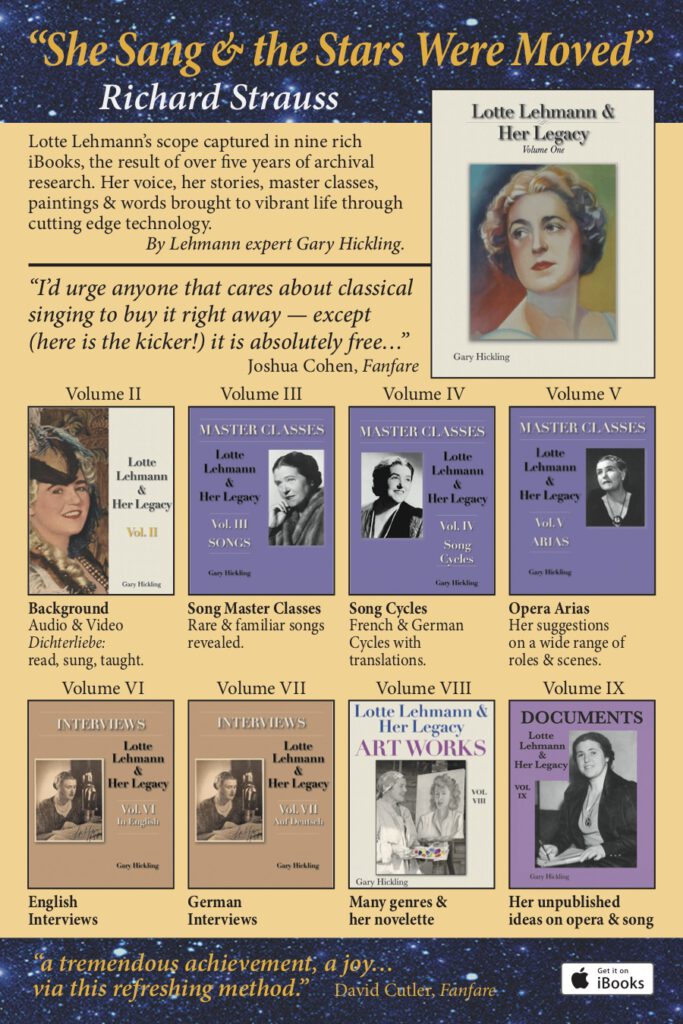

Fanfare Reviews of 9 Lehmann iBooks

Fanfare magazine has reviewed all nine volumes of my Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy in Apple Books. You can read their reviews (there are three).

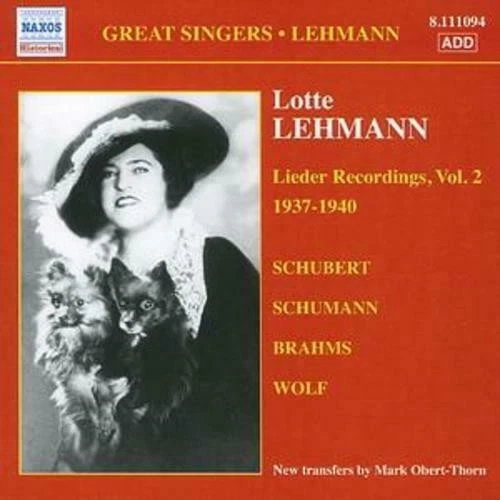

Naxos Recordings Reviewed

Lehmann’s recordings were originally shellac 78rpm discs, then they were made available in LPs, and now the CDs have been reviewed. Naxos has released Lehmann’s Lieder recorded in the US starting in 1935. Here are some reviews of these CDs.

About Naxos Volume 1

By 1935, when the earliest of the recordings on this disc were made, Lotte Lehmann was nearing 50 and had a long and distinguished career behind her. Starting at the Hamburg Opera in 1910 she got a contract with the Vienna Court Opera in 1915 and there she remained until 1937, singing 54 different roles. She was also much sought after in the rest of the world, including London, Paris, Chicago and the Met. She sang at the Salzburg Festspiele, where from 1934 her Liederabends with Bruno Walter became an institution. But Lieder had long attracted her and it is believed that she gave her first song recital in Argentina in 1922. Her recording career started well into the acoustic era with Richard Strauss’s Cäcilie and Morgen for Polydor. After a ten-year stint with Odeon she moved over to EMI for two years and then from 1935 she was under contract with Victor for five years, the result of which is collected on this disc and a companion disc to be reviewed before long.

These 64 titles, some of them never issued on 78s, were earlier available on the now defunct Romophone label but when re-mastering the transfers for this Naxos issue Mark Obert-Thorn has cleaned them further and re-equalized them to obtain a warmer sound. Sound quality is still an inherent problem since the originals were never very good with Ms Lehmann recorded too close to the microphone causing distortion. Also the piano was too backwardly recorded and had an unattractive clangy tone. As so often with these old ’uns one reacts to begin with but very quickly adjusts and accepts the sound on offer – as long as the music and the performances are good. They are. I can believe, though, that listeners unaccustomed to historical records may need an apprentice period before they get used to the narrow frequency range which robs the voice of important overtones and also, at the other end of the range, reduces the warmth and the roundness of the tone, giving an impression of squalliness. In some instances she possibly is squally so one has to take the bad with the good. In the long run the good completely overshadows the bad. The final outcome of close to 80 minutes’ listening is that one has heard some of the finest art songs of the 19th century performed by one of the finest Lieder singers of her and indeed any period. Of her contemporaries only Elisabeth Schumann on the female side could be any threat to the title “Queen of Lieder singing”, but while E.S. has life and charm in abundance she is also more uneven and her intonation and steadiness of tone sometimes falters whereas L.L. may initially seem more faceless but has a stunning security, warmth of tone and often probes even deeper when it comes to interpretations.

The lack of a face is apparent in the first Mozart song, which also is a bit relentless. Die Verschweigung on the other hand is expressive and nuanced. Schubert’s Ungeduld – uncommon to hear a female voice in this cycle conceived for a man – is certainly expressive, but here the shrillness at the top is disturbing. It seems that these first sides were something of a warming up; maybe she took a rest and had a cup of coffee – or it may be as I have already implied: one gets used to her – but from Im Abendrot (tr. 4) she only becomes better and better. The Schumann, Brahms and Wolf are all beautifully sung with exquisite nuances and care for the texts: the lively Waldesgespräch, the solemn Der Tod as ist die kühle Nacht – though the piano tone mars it, Anakreons Grab and In dem Schatten with magic pianissimo singing.

The next session, half a year later, opened with a number of lighter songs. Her accompanist, Hungarian-born Ernö Balogh – or Balough as some sources spell his name – was also a composer. Do not chide me might just as well be a Victorian parlour song from around the turn of the last century. Anyway there is nothing here to reveal his Hungarian extraction. That Grechaninov was Russian is, on the other hand, very clear. Why this Fa la Nanna, Bambin was never issued is an enigma, since this should have been a best-seller. It has a lovely melody, it is sung with honeyed tone, alluring phrasing and well judged rubatos. And who was he – Cesare Sodero? He was Italian, born in Naples, studied at the conservatory there with Martucci and graduated at the age of fourteen. After a period as touring cellist he arrived in the US in 1906, where he worked mainly as opera conductor but also as music director for gramophone companies and later radio, where he conducted hundreds of symphony concerts. He spent his last years as principal conductor of the Met.

Beethoven’s Ich liebe dich is inward and offers possibly the finest singing on the disc but she also lavishes all her considerable on the traditional Schlafe, mein süsses Kind, singing with disarming simplicity, which doesn’t come naturally to all classically schooled singers. The French songs are finely nuanced although there is some unidiomatic scooping in the Gounod.

The session on 16 March 1937 was devoted to the Austro-German school, and not only the most obvious representatives. Pfitzner surprises with a lively, folksong-like Gretel – could be late Brahms or even early Mahler. Selige Nacht shows Joseph Marx’s melodic gift. He is not too well represented in the catalogue. – the latest disc I can remember was Katarina Karnéus’s EMI Debut disc, issued some eight years ago. Robert Franz and Adolf Jensen are even more obscure and from what we can hear on this disc they should be more frequently heard.

On more familiar ground Ms Lehmann makes a lively dramatic scene of Wolf’s Storchenbotschaft, really whipping up the tension towards the end. It is obvious how Wolf’s far from easy-to-come-to-terms-with songs so often gain from being sung by an opera singer: within the narrow frame of his songs there is a wealth of expressive potential. A roughly contemporaneous recording of this song features the dramatic soprano Martha Fuchs and she also makes the most of it but her voice isn’t as attractive as Lehmann’s. Gretchen’s spinning-wheel revolves as eagerly as one could wish, “enhanced” by an uncommonly noisy pressing, and Lehmann is just as intense as Irmgard Seefried on a late recording from around 1968. For that session Seefried was about the same age as Lehmann but the latter’s voice is in far better shape: clean and steady where Seefried is decidedly worn and prone to shriek. The Wiegenlied is ample proof of Lehmann’s superior legato and she slows down towards the end when the baby has already fallen asleep. The two concluding Schumann songs, two of his loveliest creations, are again phrased to perfection.

Alan Jefferson manages to pack a lot of information into the limited space he is allotted and playing time is generous. Lotte Lehmann was undoubtedly one of the greatest singers of the last century. This and its companion discs – there is a third coming up too – give a good picture of her excellence in one field. For a fuller portrait one needs her operatic recordings as well, one of the highlights being Die Walküre act 1 with Lauritz Melchior and Bruno Walter, and the abridged Rosenkavalier from about the same time. There are also several good compilations of aria recordings from the 1920s and early 1930s but readers who are tempted to start building a Lehmann collection could do much worse than start here.

Göran Forsling

About Naxos Volume 2

MusicWeb International, June 2007

This volume follows on where volume 1 ended: in the middle of the recording session on 16 October 1937. In toto 18 titles were recorded on that occasion, evidence of Lotte Lehmann’s extraordinary stamina. There is no audible decline in her tone even in the last numbers. The highpoint is Brahms’ Botschaft where she challenges Hans Hotter’s famous reading from the mid-1950s. On the whole her Brahms is superb. Mein Mädel hat einen Rosenmund is initially sung with heavier accents than Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. The latter recorded all 42 solo songs from Deutsche Volkslieder together with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, a set that has been my touchstone recording for forty years. Then Lehmann lightens the tone and is as delightful as her heiress.

This disc is a must for every lover of German Lieder and the only possible hang-up is the quality of the recordings. Mark Obert-Thorn has done what it is possible to achieve to make them as listen-friendly as can be. In any event one soon forgets such a peripheral detail won over by the all-conquering singing.

Göran Forsling

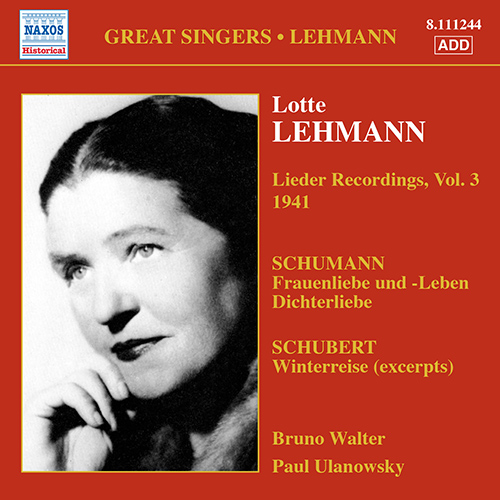

About Naxos Volume 3

Naxos have already issued two volumes in this series with Lotte Lehmann’s Lieder recordings, (Vol.1 review; Vol. 2 review) and a fourth volume is due for release in June. I waxed lyrical about the first two and for the present one I am also full of admiration, even though it is more controversial.

About Frauenliebe und –Leben there need be no question-marks at all, since this is a cycle seen from the female’s point of view. Die-hard feminists may still frown upon the lack of equality but there is no denying the deeply felt and eloquently expressed poems by Adalbert von Chamisso. Schumann’s settings of them from the Lieder year 1840 are among his finest.

Lehmann’s voice in 1941 had aged slightly, showing occasional signs of shrillness, emphasised here by the close and very clear recording. On the other hand her voice had retained much of its bloom and there is warmth aplenty. Like one of the finest exponents of this cycle from the latter half of the 20th century, Brigitte Fassbaender, she sometimes sacrifices perfectionism for expressivity. She has the same array of expressive means, of colouring the voice, though Fassbaender can sometimes be even more naked. It is also a matter of basic tessitura: Fassbaender’s deep mezzo can more easily express the darker emotions of the songs, sometimes also wringing more sorrow from them by taking them extra slowly. Since the poems, generally speaking, move from light to darkness it is also instructive to compare timings. While Lehmann is marginally slower in the first three songs, she is markedly faster in the remaining five, indicating that Lehmann sticks to a kind of middle-of-the-road tempo, whereas Fassbaender’s more expressionist approach invites wider tempo differences. It could possibly be argued that Fassbaender digs deeper but Lehmann’s readings are certainly just as heartfelt. There is a nervous eagerness in Helft mir, ihr Schwestern that is touching and when she darkens the tone for the last song, deeply moving. Bruno Walter’s accompaniments can feel a little stiff, even heavy, but that may also be the recording which seems to have been made in rather dry acoustics.

Dichterliebe, the sixteen settings of Heine’s poems, was also composed in 1840 but here we are in male territory. At first it feels weird with a bright, light, girlish voice singing Im wunderschönen Monat Mai. It is however exquisitely sung and one soon gets used to the change of vocal perspective, especially when one realises that Lehmann peers just as deep into these songs as any tenor or baritone. I have listened innumerable times to Fischer-Dieskau and Gérard Souzay and was deeply impressed by Peter Schreier’s latest recording, issued in connection with his 70th birthday. I wasn’t prepared for a soprano being just as expressive. Intimate whispers like Wenn ich in deine Augen seh’ or Allnächtlich im Traume where time stands still are so deliciously vocalised. The big, outgoing songs like Im Rhein, im heiligen Strome, Ich grolle nicht and the concluding Die alten, bösen Lieder are impressive indeed. In some other instances I felt a little disappointed, as for example in the mercurial Die Rose, die Lilie which seems far too measured. Changing ideals perhaps or simply that Bruno Walter wasn’t fleet-fingered enough to manage a faster speed. I would urge hesitant readers, though, to scrap preconceptions and give this version a listen.

Not even Brigitte Fassbaender tried Dichterliebe, as far as I know. She did however sing and record Winterreise and quite a few women singers have done so. Lehmann wasn’t even the first; that honour goes to Elena Gerhardt, who also recorded some of the songs. Lehmann recorded eleven of them during her last session for Victor in 1940 (see vol. 2) and under her new contract with Columbia the following year she set down another nine, in both cases with her regular pianist Paul Ulanowsky. The Victor session mainly concentrated on the later songs while the Columbias mostly cover the earlier ones. As with the songs on vol. 2 it is deeply moving to hear the female voice changing the perspective of the songs, making them more frail. But Gefrorne Tränen becomes gripping through her use of almost contralto chest register. In Frühlingstraum with its quick changes between bright thoughts of Spring and the darker sides of the singer’s predicament she is masterly expressive and Paul Ulanowsky is also at his best here. In the last song, Der Leiermann, the chill of the singing and the grinding of the organ send ice shivers down the spine.

My admiration for Lotte Lehmann as a Lieder singer is not only undiminished – it has grown further. The close recording of the voice leaves almost no barrier between the singer and the listener but in this case lends the songs a rare intimacy.

Göran Forsling

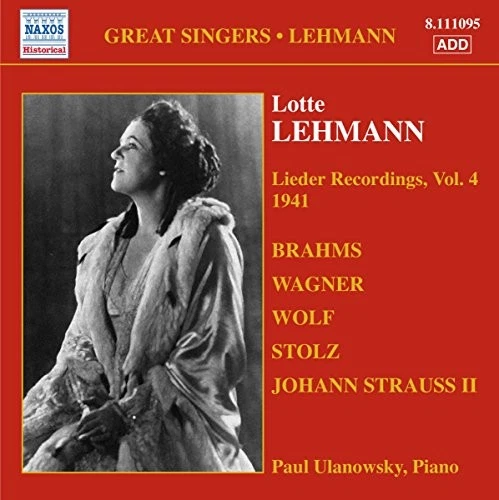

About Naxos Volume 4

On this, the fourth volume in Naxos’s series with Lotte Lehmann’s Lieder recordings, we meet her during five recording sessions and in spite of her being 53 at the time her voice is in mint condition and her insight is second to none. As before the songs are presented chronologically in the order they were recorded, except for the Wesendonck songs, which were split over two sessions and not recorded in the order they were published, but the producer, Walter Andrews, rightly wanted them to be heard together. For some inexplicable reason only two of them were published on 78 rpms and of the Wolf songs none at all. Having sung Wagner all her life she was better suited for these songs than most other sopranos and she sings them as well as any other recorded version I have heard. She also catches the varying moods of the Wolf songs to perfection, the nervously rushing Wer tat deinem Füsslein weh? perhaps the most remarkable.

Even better is her Brahms. Die Mainacht is dark and husky, the three songs from Deutsche Volkslieder (tr. 2, 7 and 8) light and warm and especially Feinsliebchen (tr. 2) is cajoled and coloured with obvious relish. An die Nachtigall is light, Auf dem Kirchhofe forceful and darkly brooding in the beginning, inward and filled resigned towards the end, sung with perfect legato. Wie bist du, meine Königin? is light and warm, Sonntag girlish and joyful, Wiegenlied simple and unaffected and, best of all, the beautiful contemplation on the moonlit nightscape of Ständchen.

The six Wiener Lieder, which conclude the disc, are sung with true affection and, having had to leave the Austrian capital three years earlier, the city, not of her dreams but of her life for so many years, there had to a large dose of nostalgia involved. Wien, du stadt meiner Träume, also a great favourite of Birgit Nilsson’s, who regularly sang it on her recitals, is sung with a light lilt and especially the reprise of the refrain is enticing. Unfortunately there is some distortion here and in the following song. Im Prater blüh’n wieder die Bäume is lovely and she caresses the slow melody in Heut’ macht die Welt, which may be a totally unknown song by Johann Strauss but in reality it is the well-known first waltz theme from Kaiser-Walzer, which Nico Dostal has adapted and amended.

Some readers may already own this compilation, since it was previously released on Romophone. Those who didn’t buy it then shouldn’t hesitate this time and they should also start saving up for the next volume in this series which will be due before long.

In short: some of the best Lieder singing from a golden era and the charming Viennese songs are sung with just as much feeling as the rest.

Göran Forsling

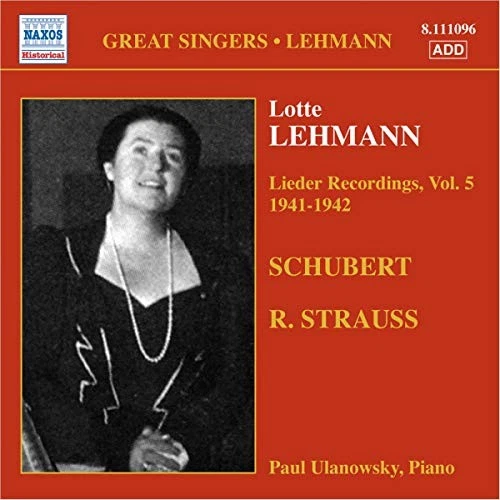

About Naxos Volume 5

MusicWeb International, July 2007

The third volume in Naxos’s Lotte Lehmann lieder recording series brings us to the three cycles she recorded in Los Angeles during 1941, though here she recorded only extracts from Winterreise. Lehmann was still in generally fine voice and though it’s idle to pretend that she had emerged technically unscathed over the years – there’s some fraying at the top of her tessitura – of far more importance is the cultivation of expression that we hear throughout the cycles.

In a sense it would have been better for her to have been accompanied by someone other than Bruno Walter in the Schumann cycles. Inspirational he may have been but he was also leaden. Starting as early as Seit ich ihn geseh’n, the first of Frauenliebe und –Leben , we find in his playing a rather pedantic, often pedagogic heaviness that occasionally seems to inhibit tempi. Lehmann though employs a full range of expressive devices in her response to the texts – diminuendi and expressive rubato in Er der Herrlichste von Allen , the flourishing chest voice in Ich kann’s nicht fassen nicht glauben , constant shading and colour without impeding the naturalness of the declamation. The boxy recording doesn’t flatter her tonally and neither does it enhance Walter who’s especially exposed in Helft mir, ihr Schwestern . Regarding studio conditions I’m nevertheless happy that Mark Obert-Thorn has resisted the temptation slightly to cushion the sound through adding artificial reverberation. Colleagues of his would probably have done so in the same way that some have added reverb to the notoriously dry Parisian studios of the 1930s – but resistance to this temptation is the better solution as far as I’m concerned.

Dichterliebe was recorded almost six weeks after the sessions for Frauenliebe und –Leben . Again Walter, for all his insights, proves technically fallible. Beyond him Lehmann’s urgency of expression, her sensitive power and her acute awareness of the balance of weight and clarity lifts the performance to the heights. One senses Walter’s particular insights too but even in, say, Hor ich das Liedchen klingen, where his imagination is at its most acute we find that he’s unable to inflect with anything like the finesse of his partner. That relatively turgid quality hems in Lehmann from time to time – try Aus alten Marchen winkt es where her natural buoyancy of rhythm exists almost in parallel to his own circumscribed efforts.

Paul Ulanowsky may not have possessed Walter’s unerring ear for text and meaning but he was a better accompanist. The gradations of tone are more sympathetic; the natural rhythm of his playing is crisper. She’d earlier recorded eleven songs from Winterreise for Victor and this Columbia set of nine proves similarly inspired in interpretative stance. To take one single example amongst so many is invidious but listen to her use of fluid portamenti in Wasserflut and how she conveys textual subtleties through the most expressive of means. As before she employs the full range of voice, from a slightly strident top to the kind of chest voice she employed so freely in Frauenliebe und –Leben . And as before the freedom of her declamation and the frequent use of ritenuti and other such devices gives her performance a powerfully personalised stamp. In the face of this both here and in Dichterliebe the voice type and sex of the singer is rendered if not irrelevant at least of marginal significance.

As noted Obert-Thorn’s work here is respectful of the originals and allows one to hear Lehmann in the full flood of her intensely communicative and overwhelmingly passionate maturity.

Jonathan Woolf

MusicWeb International, June 2007

Naxos have already issued two volumes in this series with Lotte Lehmann’s Lieder recordings, (Vol.1 review; Vol. 2 review) and a fourth volume is due for release in June. I waxed lyrical about the first two and for the present one I am also full of admiration, even though it is more controversial. ….About Frauenliebe und –Leben there need be no question-marks at all, since this is a cycle seen from the female’s point of view. Die-hard feminists may still frown upon the lack of equality but there is no denying the deeply felt and eloquently expressed poems by Adalbert von Chamisso. Schumann’s settings of them from the Lieder year 1840 are among his finest. ….Lehmann’s voice in 1941 had aged slightly, showing occasional signs of shrillness, emphasised here by the close and very clear recording. On the other hand her voice had retained much of its bloom and there is warmth aplenty…..As with the songs on vol. 2 it is deeply moving to hear the female voice changing the perspective of the songs, making them more frail. But Gefrorne Tränen becomes gripping through her use of almost contralto chest register. In Frühlingstraum with its quick changes between bright thoughts of Spring and the darker sides of the singer’s predicament she is masterly expressive and Paul Ulanowsky is also at his best here. In the last song, Der Leiermann, the chill of the singing and the grinding of the organ send ice shivers down the spine.

My admiration for Lotte Lehmann as a Lieder singer is not only undiminished – it has grown further. The close recording of the voice leaves almost no barrier between the singer and the listener but in this case lends the songs a rare intimacy.

Goran Forsling

About Naxos Volume 6

Lotte Lehmann made the interpretation of Lieder a significant part of her activity as she gradually relinquished stage rôles. By 1947, when the records included here were made, she was at the end of her operatic career, devoting most of the remaining years of her professional life (she retired in 1951) to song.

In the latter phase of her career, from 1935 onwards, she recorded an appreciable number of songs, mostly Lieder, from 1935 to 1940 with Victor in New York (available on Naxos 8.111093 and 8.111094), then with American Columbia from 1941 to 1942 (available on Naxos 8.111095, 8.111096 and 8.111244), then back to Victor for a final flowering from 1947 to 1949. Some titles, old favourites with the singer, were given a final outing, a few were new to her recorded repertory. All bear the inimitable Lehmann stamp of impulsive spontaneity and ability, above all, to communicate with us as much through the texts as through the music, and by this stage in her career, with the voice not as reliable as it once was, this emphasis on words became of the essence.

There is something about any and every Lehmann recording that provokes a gut reaction: this woman is peering into the very depths of her being and thus delving into the depths of her listener’s psyche as she relives the emotions in hand. It is also as if she were recreating the song at the moment she is singing it. That is another way of saying her art and style were wholly individual in a manner equalled in our day only by Brigitte Fassbaender.

As she herself once put it: “I like to feel that my singing is not a finite thing in itself, but rather the means of communicating my personal convictions.” All those who attended her recitals recalled those uniquely enthusiastic crowds that were Lehmann’s audience and know that these people did not come to hear her voice, lovely as nature had made it, but to experience her personal communication. As far as the discs are concerned, it is amazing how she managed to carry those attributes with her into the recording studio.

Schubert’s ‘Ständchen’ she had recorded on her days with Odeon back in the late 1920s but with one of those spurious arrangements for small orchestral ensemble that sentimentalises the original accompaniment and with most of the old ardour requisite for this favourite preserved. The use, now unfashionable, of portamento only enhances the urgency of Lehmann’s serenade.

Brahms’s Zigeunerlieder, written in 1887, were new to her discography. Obviously she wanted to commit to disc her wonderfully uninhibited rendering of these gypsy-inspired songs. Brahms was never so happy as when writing in this folk-like vein, here based on Hungarian originals, and Lehmann, with her faithful partner, Paul Ulanowsky, responds in typically wholehearted manner to their varying moods. ‘Brauner Bursche’ is a template of the whole set in Lehmann’s reading. Over the fifty or so years since they were recorded, they have lost little of their immediacy of impact, the Lehmann warmth of tone and manner irresistible here as everywhere. To date the originals have had small currency, so their reappearance is doubly welcome.

Schubert’s ‘An den Mond’, his setting of Hölty, not Goethe, was again new to the singer’s recorded repertory: she enters delicately into its night-haunted mood. ‘An die Musik’ was, naturally enough, a regular of her recital programmes – she broke down when singing it at her farewell in Carnegie Hall in 1951. Again she had recorded it in her Odeon days with inappropriate accompaniment. Here, with Ulanowsky, she goes to the heart in praise of her own and Schubert’s art.

Brahms’s ‘Feldeinsamkeit’, a piece particularly suited to Lehmann’s dark, velvet-like timbre, is another song she was tackling for the first time on disc, and she gives it a suitably warm reading. She does the same for much less familiar Lied by Brahms, ‘Der Kranz’.In the graphic description of the eponymous blacksmith in ‘Der Schmied’, whose hammering is heard in the piano, Lehmann is at her most fulsome and free.

Like many great singers, yesterday and today, Lehmann liked to please the popular market. The famous German Christmas song ‘Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht’ was always in her song bag: this is her third and last recording. She also liked to show off her English, especially during her years in the United States. It was heavily tinged with a German accent, which makes her account of ‘O Come All Ye Faithful’ that much more endearing.

The next three short Schubert songs were fresh to the Lehmann discography. They are typical of late Lehmann in their renewed emphasis on telling a story, also for that joy in the very act of singing which now – near the end of her long career – she was keen to deploy on new material in recital and on the concert platform, for she was never one just to continue purveying old favourites. ‘Der Erlkönig’ is another matter. Her 1930 recording with orchestra sounds inauthentic now; able to record how she liked, she reverted to singing the dramatic ballad with the electrifying piano part – and Ulanowsky – in support. In broadcasts Lehmann liked to give an anticipatory introduction, telling her story in a melodramatic manner entirely appropriate to the fantasy of the song. Her interpretation, as you would expect from an opera singer familiar with the stage, is painted on a generous canvas, all four participants carefully characterized, consoling us for some squally moments in the vocal production.

‘God Bless America’, the alternative American national anthem, was obviously picked as a popular favourite and as a way of thanking her adopted homeland. ‘The Kerry Dance’, on the other hand, is one of those eccentricities even the best singers occasionally indulge in, way out of their regular world. The singing of the vocalised ‘Träumerei’ is an exercise in pure nostalgia.

Finally comes a reminder of Lehmann’s interest in French song. She had already recorded ‘Vierge d’Athènes’, Gounod’s subtle, sensuous setting of a translation of a poem by Byron, in 1935 (Naxos 8.111093). It is interesting that the composer/singer Reynaldo Hahn made a fascinating 78rpm disc of ‘Vierge d’Athènes’, and that it is to Hahn that Lehmann turned for two of her last six official records, made in May 1949. She catches the sensuous mood of ‘L’enamourée’ precisely and also the understated sense of utter betrayal in love so unerringly projected in ‘Infidélité’, one of Hahn’s very best mélodies. She also goes to the heart of Duparc’s inward ‘La vie antérieure’ and Paladilhe’s fine song ‘Psyché’.

But for the last official recordings of all she returned to her beloved Strauss. Once more her heart is poured out, this time in three songs that she had never committed to disc before. The sincerity and involvement of the singing is as it had been throughout the 35 years of her career in the studio, encompassing more than 450 recordings.

Ulanowsky was an Austrian, thoroughly conversant with the piano repertory. He was the Vienna Philharmonic’s resident pianist for ten seasons before leaving for the United States in 1935 to act as accompanist to the mezzo Enid Szantho. Two years later he met Lehmann and immediately set up a rapport with her, as can be graphically illustrated here as he follows faithfully those rhythmic variations in which she indulged. Their rapport seemed instinctive.

© Alan Blyth

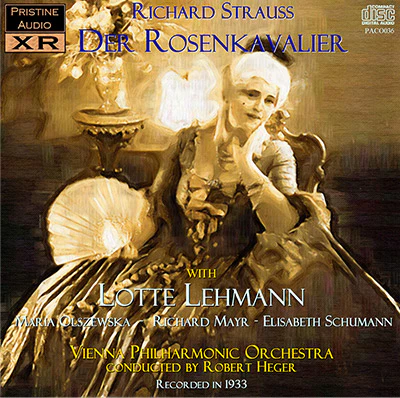

About Pristine Der Rosenkavalier

No one who loves this music can afford to be without this recording.

Recorded almost eighty years ago it is remarkable how much information was hidden on the twenty-six shellac sides. In his technical notes on the Pristineclassical website Andrew Rose claims to have opened up the top end of the frequency range to somewhere around 10kHz through use of with the use of XR technology. That’s ‘roughly double the expected frequency response for a set of 78s’. The risk is that there are also hidden shortcomings, primarily ‘the dreaded swish’. Today it is possible to eliminate swish without affecting the music – but it has to be done one swish at a time and on this set it is a question of more than 9000! Obviously it’s a very laborious task.

Eight years ago Naxos issued this set, restored by Mark Obert-Thorn; also on Andante. Since then there have been important technological advances. Unfortunately I haven’t had access to that earlier set, but I have several snippets from this legendary recording on various LPs and the difference is amazing. First and foremost we hear so much more of the orchestra. The introduction, so magically scored, now unfolds with a clarity and richness of detail that one couldn’t have dreamed were inherent in the old shellacs. The velvety strings of the Vienna Philharmonic caress the ear with marvellous warmth and the pizzicato playing in the introduction to act III is extraordinarily well-defined. The delicious final bars are also pin-point clear. The voices are well defined and even though dynamics are limited compared to more recent efforts there is an overall quality that should make this issue attractive even to those who normally are allergic to historical recordings.

The performance in itself is a true classic and it has been hailed uncountable times. Let me just add to the laurels heaped upon it with a few personal notes. It is heavily cut, so heavily that it is not even an abridged version but ‘Selected passages’ as the header correctly states. The whole reception scene in act I is gone, thus also the Italian tenor’s Di rigori armato. Great portions of Baron Ochs’s boisterous behaviour in act II are also cut as well as much else. An uncut performance takes a little more than three hours; this one plays for 98:26, not 118:26 as stated on the inlay. In other words about half the score is cut out. What remains offers what is indubitably the best of the opera, very much concentrated around the four leading characters.Of these Richard Mayr, who was nearing the end of a more than 30-year-long career and died only two years later, was a little past his best. His tone had dried out compared to what he sounded like a decade earlier. He was however the Ochs of his time in Vienna, where he sang in the first performance on 8 April 1911. By 1933 he had chiselled out a many-faceted portrait that made the character less bullish, more likeable than he actually is. Whether this is good or bad is open to debate.

Lotte Lehmann and Elisabeth Schumann, arguably the two best sopranos in the Austro-German repertoire during the years after WW1, were still at the zenith of their careers. Both incidentally were born the same year, 1888, and thus in their mid-forties. Lehmann has never been surpassed in the role of Feldmarschallin – though Elisabeth Schwarzkopf was her equal. Hers is a portrait of deep insight and sensitivity. Schumann is possibly the most charming Sophie ever and though there are imperfections – the odd note off-pitch, some exaggerated portamenti – this is negligible in the face of such identification and loveliness.

Maria Olszewska’s Octavian is not quite in their class. She sings well and her round and darkish tone is well contrasted to the two sopranos’ but as an interpreter she is anonymous, compared to some later singers of the role: Christa Ludwig, Yvonne Minton, Frederica von Stade and Anne Sofie von Otter. That said, in the duets and trios she is a rock-solid complement to the lighter and brighter voices and the finale is a vocal treat from beginning to end.

Robert Heger may have been an able rather than extraordinary conductor, but he seems to have been particularly fond of this score and draws lovely playing from the admirable Vienna Philharmonic.

No one who loves this music can afford to be without this recording and with the new-dimensional sound that Andrew Rose has conjured up from the old records there is further reason to procure this pair of Pristine Audio discs.

Göran Forsling

Record Reviews: Frauenliebe und -leben

The following review is from the March/April 2017 issue of FANFARE magazine.

Remember back around 1960, when the bootleg TAP record label issued an LP of 40 different tenors in historic recordings of “Di quella pira” from Verdi’s Il trovatore ? (Well, to be honest, I don’t remember it either, being less than two years old at the time. But the friend who introduced me to historic vocal recordings when I was 20 owned a copy.) Well, here we have nothing so obsessively single-minded, but rather quite a good idea indeed: a collection of eight different historic recordings of Schumann’s beloved song cycle, set down over a 23-year span….

– Lotte Lehmann (sop), Paul Ulanowsky (pn), 2/20/1946 (live, New York – Town Hall recital)….

…Choosing a favorite version from this embarrassment of vocal riches risks being a churlish exercise; but if forced to do so, I would unhesitatingly plump for the opening account with Lotte Lehmann (1888–1976). Hers is a magisterial reading of the widowed subject of the poems looking back over her life, rendered with sovereign majesty over her art and unmatched degrees of subtle shading and inflection of the texts. Although she was one week shy of 58 when she gave this recital, her voice is in pristine condition, and the excellence of this rendition is heightened by the sensitivity of her longtime accompanist, Paul Ulanowsky. Richard Caniell has rightly chosen to employ only minimal filtering of somewhat noisy acetates (though these are no worse than many 78-rpm discs from the same period) in order not to impair Lehman’s tonal coloration. Despite being a live performance, no audience noise is perceptible; applause is not included. The sound is vastly superior to that on an Eklipse release from 1995.

James Altena

Record Reviews: Komm Hoffnung from Fidelio

In the November 2022 edition of Music and Musical Performance, Stephen Hastings wrote “Ten Portraits in Sound of Beethoven’s Leonore.” Though the complete article is an interesting read, here are the Lotte Lehmann references:

After a positive response to Lilly Hafgren’s recording of the Liebestod from Beethoven’s Fidelio, he writes:

“For those who do prefer a more classically poised approach, the disc made four years later

by the slightly older Helene Wildbrunn (described by Lord Harewood in Opera on Record as

“the best of the acoustics”) or Frida Leider’s famous 1928 electrical recording may offer

greater satisfaction, but the only other version from the 1920s that can compare with Hafgren’s

in terms of freshness of tone and immediacy of feeling is Lotte Lehmann’s 1927 recording

conducted by Manfred Gurlitt, made in the centennial of Beethoven’s death, about eight

months after her debut in the role (on March 31) at the Vienna Staatsoper. There is no

recitative here, unfortunately, and the Berlin orchestra is unremarkable, but the electrical

recording lends exceptional presence to a voice of rare beauty and unique communicative

directness. Her reading matches Hafgren’s in its urgency but goes one step further, lending an

even stronger emotional resonance to individual words. The nouns “Liebe” and “Müden,” the

adjective “fern,” the verb “komm,” and the pronoun “du” are all vividly alive, evoking a clearly

defined physiognomy and enabling us to share Leonore’s imaginative life at the deepest level.

This ability has much to do with the singer’s capacity for feeling, but the responsiveness of the

voice as an emotionally expressive instrument is equally decisive. Lehmann is not the only

soprano here to invest the word “Liebe”—featured five times in the Adagio—with particular

warmth, slowing the tempo and building a crescendo when the first syllable is sustained for

more than a whole measure. Yet in her case the emotional impact is strengthened by a

broadening of vibrato achieved much in the manner of a string player, for Lehmann’s is one of

those voices that seem to be able to vary the vibrato at will, while the warm caress of her

diction makes us more aware than with any other singer that this word often coincides with a

return to the tonic and therefore represents the emotional keystone of the whole scene. No

Leonore on record is more loving than this one.

The German soprano—who was thirty-nine at the time—also surpasses Hafgren in the

strength of her legato. Although her relatively short breath spans—a technical defect that she

never overcame—force her to break some phrases (including the one at the end of the Adagio)

that the Swede sings without interruption, she demonstrates how a strong emphasis on

consonants (witness the eloquent initial k in “komm” and the much-repeated ch sounds: softer

and more drawn out than in any other performance here) can reinforce, rather than weaken,

the binding of vowels within a phrase. The portamentos written by Beethoven become an

integral part of the expressive mood of the Adagio: a prayer to hope (“Hoffnung”) in which

that abstract concept seems to acquire a tangible presence. It really sounds as if Leonore’s life

depends on every word that is uttered, and her repetition of “erhell’ mein Ziel” (instead of the

written “erhell’ ihr Ziel”) in mm. 60–61 seems to reflect the intensely personal character of her

prayer—although in this case (unlike Lilli Lehmann’s similar “error”) there is no textual basis

for the variant. The almost breathless intensity of the soprano’s verbal articulation explains

why dynamics lean more toward forte than piano, with no sustained use of the mezza voce. In

the score there are in fact no dynamic markings in the vocal line, and although the indications

for the orchestra offer useful hints, they should not necessarily be respected by the singer in

every phrase. The opening of the Allegro con brio—“Ich folg’ dem innern Triebe”—needs to

be attacked with a certain vigor (and Lehmann undeniably achieves this): here the piano in the

instrumental parts is surely designed to guarantee the voice sufficient audibility on the

multiple low Es, a tricky note for a soprano. Lehmann’s voice in fact sounds healthy and easily

produced throughout the two-octave range (from the B below the staff to the one above it) and

we are never aware of any awkward technical maneuvers, although in the Allegro the soprano

has to slow down to cope with the wide-ranging pairs of eighth notes in “mich stärkt die

Pflicht der treuen Gattenliebe” and takes a conspicuous breath between the two ascending

scales leading to the final cadence. The top B is radiant, however, and she approaches the

conclusive E by means of a heavily weighted appoggiatura that lends the ending an emotional

effusiveness that contrasts with Hafgren’s baldly heroic resolution. And nine years later, in a

shortwave radio broadcast of a Salzburg Festival performance under Arturo Toscanini on

August 16, 1936, she retains the appoggiatura but otherwise executes the penultimate

measure of the vocal part almost exactly as printed in the score, where the top B is followed by

an arpeggio ascent to an A before resolving on the tonic—only that these notes are in fact

transposed half a tone downward (as is the whole scene beginning with the words “der

spiegelt alte” in the recitative). Beethoven writes ad libitum above this cadence—suggesting

that an alternative cadenza (there are fermatas on both the B and the A) could be inserted if

one wished—but it is rare indeed for a singer to introduce a personal flourish here and most

prefer to sing the simplified version of what is written (with the B followed—via the leading

tone—by the return to the tonic), which is undeniably effective if the risky top note turns out

to be sufficiently resounding. The live broadcast with Lehmann is in poor sound, but once

again verbally vivid, with more gently tapered phrasing in the Adagio, where the soprano

establishes a stronger contrast between the thirty-second and sixteenth notes in the long

upward scale: a contrast highlighted also by Greeff-Andriessen and Wildbrunn. The recitative

is sung with great vigor and beauty of tone, with all the appoggiaturas in place and a

portamento linking the first two syllables of “Farbenbogen”: an image (of a rainbow) that

naturally benefits from a binding effect.

There are no unwritten portamentos in Kirsten Flagstad’s recordings of this scene. (She

was always a rather literal-minded singer.) Nor, in spite of her limpid pronunciation of the

text, is her word-painting anything like as vivid as Hafgren’s or Lotte Lehmann’s. Yet it was

the Norwegian soprano who dominated the role internationally from the late thirties to the

early fifties and the reasons are very clear in the 1950 Salzburg Festival broadcast, where the

soloist is recorded at a greater distance than in her earlier and later Met airchecks (1936–51) but

reveals an exceptional musical empathy with Wilhelm Furtwängler (arguably the finest

Beethoven conductor of the twentieth century) and the Vienna Philharmonic: an ideal

orchestra for this music. The performance the conductor draws from the soprano is less rich

in dramatic contrasts than the one she gave at the Met under Bruno Walter in 1941, but

Walter—who probably considered Lotte Lehmann his ideal—felt that Flagstad’s Leonore

remained “emotionally unconvincing” in spite of his guidance—…”

Stephen Hastings

Record Review: Die Walküre 1939 “live”

In the May/June 2013 issue of Fanfare magazine, Henry Fogel writes of the “Immortal Performances” release of Die Walküre.:

Richard Caniell’s restoration of this 1939 broadcast surpasses all previous issues in quality, even including the Met’s own lavishly produced (and lavishly priced) LP set. The sound is fuller, the voices truer and more natural, the sonic grit minimized to a degree I would not have thought possible…The sound is now listenable to anyone with an ear attuned to ‘historic’ recordings, in a way that it never has been.

So why can you not be without this? Primarily, but not solely, Lotte Lehmann in one of her greatest roles, caught in terrific voice and in a real performance….Her Marschallin is one of the truly great operatic characterizations, worthy of mention with Chaliapin’s Boris and Caruso’s Canio, and to have it in this form is to have a treasure. In addition we get the young Risë Stevens’s deftly characterized and beautifully sung Octavian, a relatively unknown Sophie in Marita Farell, but one who sings with the pure silver tone this music wants.

This is a hugely important release to anyone who cares about this opera; even if you have the performance in an earlier incarnation, replacement is urgently recommended.

Henry Fogel

Record Review of a Rosenkavalier Recording

In the Spring 1999 edition of International Opera Collector Hugh Canning wrote of a Rosenkavalier recording:

The most famous of pre-war Marshallins was unquestionably Lehmann, one of the great Elsas and Sieglindes of her day, who created the lyric soprano role of the Composer in the Vienna premiere of Ariadne II and the dramatic soprano role of the Dyer’s Wife in Die Frau ohne Schatten. Lehmann’s voice must have developed gradually into the heavier parts, for she is the first of several celebrated Rosenkavalier ‘hat-trick’ holders: sopranos who have progressed from Sophie to Octavian to the Marshallin….Lehmann was clearly one of the sopranos who served as inspirational muse to Strauss: in addition to the Composer and Dyer’s Wife, she was also entrusted with the creation of one of his most individual and beloved protagonists, Christine Storch in Intermezzo, a thinly disguised portrait of Strauss’ wife Pauline. [One shouldn’t forget that his Arabella was written with LL in mind].

Lehmann’s dramatic conception of the [Marschallin] manages to convince despite her age: she is coquettish with both Octavian and Ochs, using a sly portamento (‘Du, Schatz!’) to convey her amusement at the Mariandel disguise, and she seems more tolerant than most of her successors of her ‘aufgeblasene, schlechte Kerl’ of a cousin. Indeed, from the histrionic point of view, Lehmann maintains the melancholic and frivolous sides of the Marschallin’s personality in carefully balanced equilibrium: the dry eye much in evidence in her teasing of her lover and remonstrations with Ochs, the wet one in her nostalgic reminiscences of ‘die kleine Resi’ fresh from the convent in the Act 1 monologue and especially in the ‘Heut’ oder morgen’ section the the succeeding duet with Octavian. Long experience of the opera has evidently led to a deep understanding of the Marschallin’s mercurial temperament: her tears are not self-pitying ones and they do not for long dull the twinkle in her eye…”

Hugh Canning

Live Rosenkavalier Review

This critic writes about the Live 7 January 1939 Met performance available on Naxos “Immortal Performances.”

Review of 1936 Die Walküre Act II

Music & Arts has released a restored 1936 Die Walküre (Act II) with Lehmann, Flagstad, Melchior, et al., conducted by Reiner from new source material. A copy arrived and I compared it to their earlier (1999) version. This one is much less raw, (better source material) and easier listening. Some may prefer the first publication for its primitive, slightly more exciting edge. But for me, this 2013 release, still with surface noise, is a joy. As I listen to more of these older live recordings, the importance of a good conductor becomes more apparent. Reiner fills that requirement. And the singers are uniformly as good as their reputations would predict. Since it’s just Act II Lehmann only singsSince it’s just Act II Lehmann only sings for a short time, but it’s dramatic, powerful and believable in its dramatic intensity.Music & Arts has released a restored 1936 Die Walküre (Act II) with Lehmann, Flagstad, Melchior, et al., conducted by Reiner from new source material. A copy arrived and I compared it to their earlier (1999) version. This one is much less raw, (better source material) and easier listening. Some may prefer the first publication for its primitive, slightly more exciting edge. But for me, this 2013 release, still with surface noise, is a joy. As I listen to more of these older live recordings, the importance of a good conductor becomes more apparent. Reiner fills that requirement. And the singers are uniformly as good as their reputations would predict. Since it’s just Act II Lehmann only sings for a short time, but it’s dramatic, powerful and believable in its dramatic intensity.

Lehmann’s Dichterliebe

In the 26 April 2023 issue of VAN magazine you’ll find: A “Dichterliebe” All-Stars Playlist

One poet’s love across 80 years of recordings by Jeffrey Arlo Brown

Lotte Lehmann and Bruno Walter: “Die Rose, die Lilie, die Taube, die Sonne” (1954) [really 1941]