I was too young to have heard Lehmann live in either opera or recital modes, but have always heard the same admonition: “The recordings, no matter how good, are nothing compared to experiencing Lehmann live!”

Here’s what her friend, colleague, and later, biographer Beaumont Glass wrote about this subject: “No records, however, can recapture the visual component, the overwhelming impression she created through the combination of facial expression, personal magnetism, and stage presence—a kind of magic—which remained hers as long as she lived and which came across as effectively in her master classes as it had at the height of her career. Her whole being became the song.” Glass further wrote: “For those who were there, a Lehmann performance was something very special and quite unforgettable. The love that flowed back and forth between artist and audience was something wonderful to feel. Nothing was ever routine, not even for a moment; every moment was an experience, intimately shared.”

Though you may already sample several pages on this site where both recorded and live performances are offered, I’d like this page to provide a wide variety of such comparisons. But here are the pages mentioned that do contain both live and studio-recorded pieces: Hear how Lehmann sang Schubert’s Ständchen (Leise flehen…); Lehmann’s performances of Schubert’s Der Doppelgänger; Lehmann’s recordings of Schumann’s Frauenliebe und -leben.

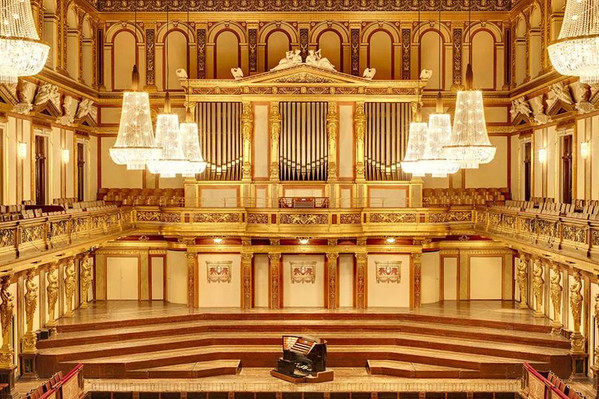

Da geht er hin from Der Rosenkavalier by Strauss

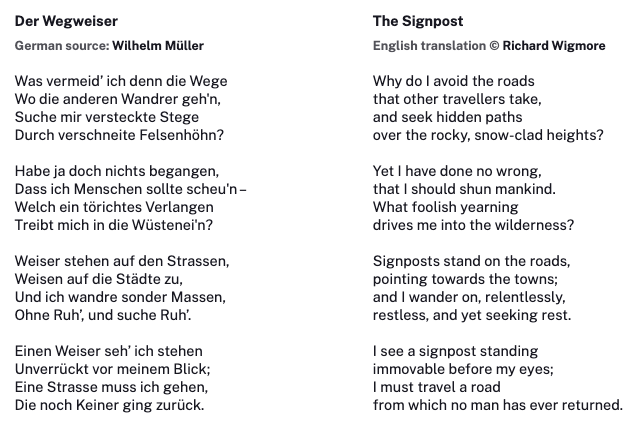

Let’s begin with Lehmann’s most famous role, that of the Marschallin from Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss. “Da geht er hin” summarizes the Marschallin’s feelings about Baron Ochs and recalls her youth and present status. Below, you’ll find the words and translation. First, we’ll hear Lehmann sing this monolog from a Metropolitan Opera performance broadcast on January 7, 1939. The conductor is Artur Bodanzky. Remember that this was broadcast on the AM radio (FM hadn’t been invented yet) and an aficionado recorded it from their radio speakers onto acetate discs. After that you can hear the “studio” recording from 1935. Studio isn’t quite the right word because the Rosenkavalier excerpts were recorded in the Großer Musikvereinssaal in Vienna with the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Robert Heger. As with the Walküre recording mentioned below, the other singers, etc. were part of the “audience” of the recording.

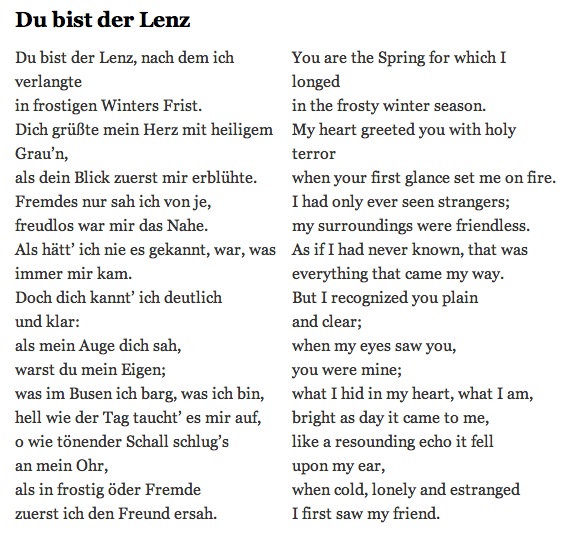

Du bist der Lenz from Die Walküre by Wagner

If the Marschallin is the role for which Lehmann is most famous in the U.S., her Sieglinde was of such renown that none other than Bruno Walter conducted the 1935 recording of the first act of Die Walküre and excerpts from the second act. Thereafter, the Nazi regime stepped in and removed any Jews and other unwanted people from the historic recording.

We’ll hear first, a 1930 electric recording of Du bist der Lenz (which Lehmann had already recorded twice in the acoustic format) with Frieder Weissmann conducting members of the Berlin State Opera Orchestra. This is truly a studio recording. That will be followed by the 1935 Bruno Walter recording mentioned above, which was also recorded in the Vienna Großer Musikvereinssaal, also considered a studio recording. But the difference is that it was not in an actual studio, but in a hall that the singers, musicians, etc. all knew well and the other singers were there for the moments that they’d be recorded. So in effect, Lehmann (and Lauritz Melchior, Emanuel List, etc.) were all listening to each other, hardly the case in a regular studio recording. The final Du bist der Lenz that you’ll hear is actually from a live performance that was broadcast and thus preserved. The performance took place on March 30, 1940 at the Metropolitan Opera. Some of the surface noise may be distracting, but Lehmann’s great sound and involvement are never in question.

Horch, o horch from Die Walküre by Wagner

In the following excerpt, Horch, o horch, we’re in the second act of Die Walküre. We’ll begin with the live version from November 13, 1936 with Fritz Reiner conducting the San Francisco Opera. That will be followed by the Bruno Walter 1935 recording. Remember that in contrast to the ecstatic Du bist der Lenz heard above, Sieglinde is at this point witnessing the almost certain death in battle of her newly discovered love, Siegmund.

Horch! o horch! das ist Hundings Horn!

Seine Meute naht mit mächt’ger Wehr:

kein Schwert frommt vor der Hunde Schwall:

wirf es fort, Siegmund! Siegmund, wo bist du?

Ha dort! Ich sehe dich! Schrecklich Gesicht!

Rüden fletschen die Zähne nach Fleisch;

sie achten nicht deines edlen Blicks;

bei den Füßen packt dich das feste Gebiß

du fällst in Stücken zerstaucht das Schwert:

die Esche stürzt, es bricht der Stamm!

Bruder! Mein Bruder!

(Sie sinkt ohnmächtig in Siegmunds Arme.) Siegmund, ha!

Listen! o listen! that is Hunding’s horn!

All his pack pursue in mighty force:

no sword helps you against the hounds:

let it go, Siegmund! Siegmund, where are you?

Ha, there! I see you now! Terrible sight!

Dogs are gnashing their teeth after flesh;

no heed they take of the hero’s glance;

by your feet they seize you with fast-holding fangs.

You fall; in splinters the sword has sprung:

the ash-tree sinks, the stem is broken!

Brother! my brother!

(She sinks senseless into Siegmund’s arms.) Siegmund, ha!

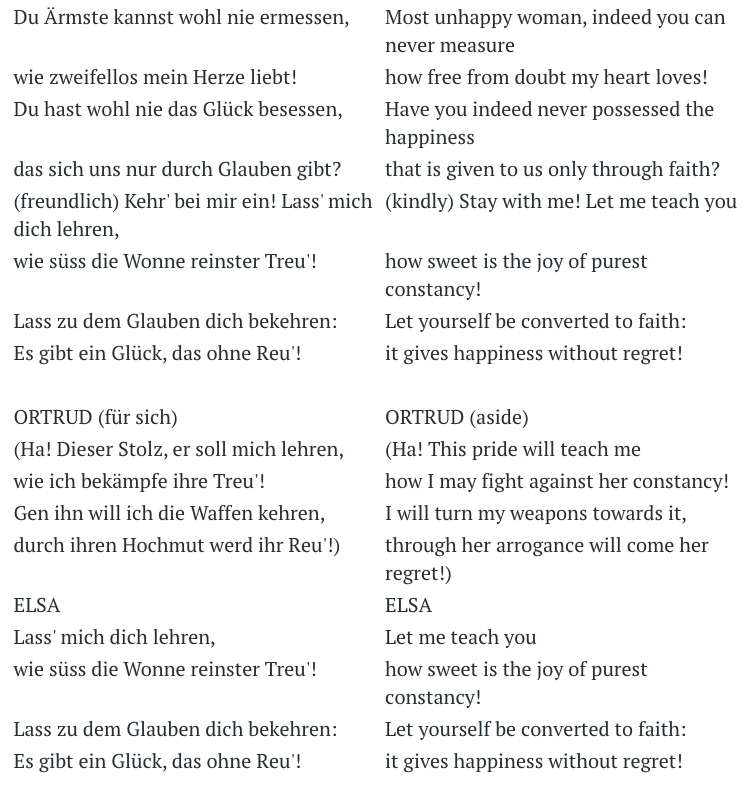

Du Ärmste kannst wohl nie ermessen from Wagner’s Lohengrin

Sadly there aren’t many live recordings of Lehmann’s opera performances. But since many concerts and recitals were broadcast and thus recorded on acetates, we do have some good comparisons with the studio recordings of the same era. From January 10, 1937 we have a section of Wagner’s Lohengrin: Du Ärmste kannst wohl nie ermessen with the NBC Orchestra conducted by Frank Black and broadcast for the RCA Magic Key. This is, then, not an actual opera performance, but also not a studio recording, because there was an audience present. The only studio recording we have of this excerpt is from 1916. No orchestra or conductor is credited for this acoustic recording. There are thus two comparisons to listen for: Lehmann was at the beginning of her career and had at the age of 28 just made her name as Elsa in Lohengrin. The Magic Key recording found Lehmann, having sung the role at least 80 times, still in beautiful voice at the age of 49.

Ständchen by Strauss

There are many options to choose from when we deal with Lehmann’s Lieder. Let’s compare this live performances of Ständchen by Strauss from April 3, 1938, with the NBC Orchestra conducted by Frank Black and broadcast for the RCA Magic Key. For the 1941 Columbia studio recording, the pianist is Paul Ulanowsky. Purists complain that Lehmann held the final “hoch” at least twice as long as written. I was sitting with Lehmann at the back of the auditorium at the Music Academy of the West for Martial Singher’s masterclass. When the student singer took this same liberty, Singher wondered aloud if this was permitted. Without missing a beat, Lehmann stood and said “Ja, Strauss told me…” and the rest of her statement was drowned out by surprised laughter and applause. The other complaint is that Lehmann took a catch breath before the final “der Nacht.” Some vocal experts would suggest that she just ran out of breath, while others would note the kind of extra emotion that fills those last two notes because of the extra breath.

Ständchen

Poet: Adolf Friedrich von Schack

Mach auf, mach auf! doch leise, mein Kind,

Um Keinen vom Schlummer zu wecken!

Kaum murmelt der Bach, kaum zittert im Wind

Ein Blatt an den Büschen und Hecken;

Drum leise, mein Mädchen, daß nichts sich regt,

Nur leise die Hand auf die Klinke gelegt!

Mit Tritten, wie Tritte der Elfen so sacht,

Um über die Blumen zu hüpfen,

Flieg leicht hinaus in die Mondscheinnacht,

Zu mir in den Garten zu schlüpfen!

Rings schlummern die Blüten am rieselnden Bach

Und duften im Schlaf, nur die Liebe ist wach.

Sitz nieder! Hier dämmert’s geheimnisvoll

Unter den Lindenbäumen.

Die Nachtigall uns zu Häupten soll

Von unseren Küssen träumen

Und die Rose, wenn sie am Morgen erwacht,

Hoch glühn von den Wonneschauern der Nacht.

Open up, open up! but softly, my child,

So that no one’s roused from slumber!

The brook hardly murmurs, the breeze hardly moves

A leaf on the bushes and hedges;

Gently, my love, so nothing shall stir,

Gently with your hand as you lift the latch!

With steps as light as the steps of elves,

As they hop their way over flowers,

Flit out into the moonlit night,

Slip out to me in the garden!

The flowers are fragrant in sleep

By the rippling brook, only love is awake.

Sit down! Dusk falls mysteriously here

Beneath the linden trees.

The nightingale above us

Shall dream of our kisses

And the rose, when it wakes at dawn,

Shall glow from our night’s rapture. (It will blush at what transpired!)

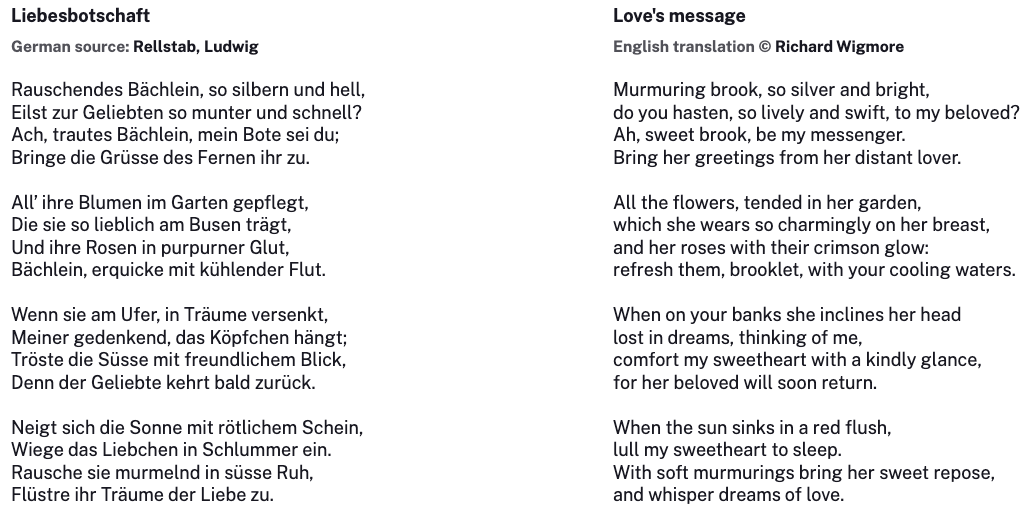

Liebesbotschaft by Schubert

The next Lied performance is a mystery. Lehmann recorded Schubert’s Liebesbotschaft with Ulanowsky for Columbia on 19 March 1941, matrix CO 30017-1. It wasn’t published on 78s and the only LP release was in Japan: YD 3017/18. Lehmann’s delightful recording allows her light-hearted happiness to sing forth. Listeners were thus delighted when the following supposedly live recording was discovered, in spite of the fact that it is probably a test pressing. I’ll offer both, but I believe they are actually the same recording with slightly different systems cleaning up the original noise etc.

Die alten, bösen Lider from Dichterliebe by Schumann

In 1941 Lehmann recorded Schumann’s complete Dichterliebe (Poet’s Love) in the studio with Bruno Walter as pianist. Though we only have excerpts from a 1943 Town Hall recital of the same cycle, it’s a joy to hear Paul Ulanowsky on the piano. His style of playing is more modern than Bruno Walter’s, and he allows Lehmann more interpretive options. And Lehmann is always more spontaneous with an audience. Listen to her abandon as she immerses herself in this song. This is the last song of Dichterliebe and we have the chance to hear just how bitter Lehmann can sound (Wißt ihr, warum der Sarg wohl/So groß und schwer mag sein?) and how poetic Ulanowsky’s pianism can be (especially the postlude).

Die alten, bösen Lieder,

Die Träume bös und arg,

Die laßt uns jetzt begraben,

Holt einen großen Sarg.

Hinein leg’ ich gar manches,

Doch sag’ ich noch nicht, was;

Der Sarg muß sein noch größer,

Als Heidelberger Faß.

Und holt eine Totenbahre,

Und Bretter fest und dick;

Auch muß sie sein noch länger,

Als wie zu Mainz die Brück’.

Und holt mir auch zwölf Riesen,

Die müssen noch stärker sein

Als wie der starke Christoph

Im Dom zu Köln am Rhein.

Die sollen den Sarg festgraben,

Und senken ins Meer hinab;

Denn solchem großen Sarge

Gebührt ein großes Grab.

Wißt ihr, warum der Sarg wohl

So groß und schwer mag sein?

Ich senkt auch meine Liebe

Und meinen Schmerz hinein.

The old, angry songs,

The dreams angry and wicked,

Let us now bury them,

Fetch a large coffin.

In it will I lay many things,

But I will still not say quite what;

The coffin must be still larger,

Than the cask in Heidelberg.

And fetch a death bier,

And planks firm and thick;

They must be still longer,

Than the bridge to Mainz.

And fetch me, too, twelve giants,

They must be still stronger

Than that strong St. Christopher

In the Cathedral to Cologne on the Rhine.

They should carry the coffin away,

And sink it down deep in the sea;

Since such a great coffin

Deserves a great grave.

Do you know why the coffin

Must be so large and heavy?

I sank with it my love

And my pain, deep within.

Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht by Brahms

Lehmann recorded Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht by Brahms in the studio in 1935. Her pianist was Ernö Balogh. The live performance has more languor and spaciousness. Even though that live performance was in 1949, her vocal estate actually seems freer as she easily manages the range of a 10th. As for interpreting this Lied: Does the song of love outlast life and death, or are the peace and darkness of death more important than love? Typical Heine poetry!

Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht,

Das Leben ist der schwüle Tag.

Es dunkelt schon, mich schläfert,

Der Tag hat mich müd gemacht.

Über mein Bett erhebt sich ein Baum,

Drin singt die junge Nachtigall;

Sie singt von lauter Liebe,

Ich hör es sogar im Traum.

Death is the cool night,

Life is the sultry day.

It now grows dark, I’m drowsy,

The day has wearied me.

Above my bed rises a tree,

The young nightingale sings there;

She sings only of love,

I hear it even in my dreams.

Anakreons Grab by Wolf

Hugo Wolf wasn’t a well-known composer when Lehmann began her career, but in Vienna she met and worked with one of Wolf’s friends who introduced her to the vast number of excellent Wolf Lieder. Certainly Anakreons Grab (Anacreon’s Grave), to the poetry of Goethe, became one of her favorites. A meditative text and setting combine to make this a profoundly moving song that obviously touched the poet in Lehmann.

Wo die Rose hier blüht,

Wo Reben um Lorbeer sich schlingen,

Wo das Turtelchen lockt,

Wo sich das Grillchen ergötzt,

Welch ein Grab ist hier,

Das alle Götter mit Leben

Schön bepflanzt und geziert?

Es ist Anakreons Ruh.

Frühling, Sommer, und Herbst genoß

Der glückliche Dichter;

Vor dem Winter hat ihn endlich der Hügel geschützt.

Here where the rose blooms,

Where vines entwine the laurel,

Where the turtledove calls,

Where the cricket delights,

Whose grave is here,

That all the gods with life

Have so beautifully planted and decorated?

It is Anacreon’s rest [resting place].

Spring, summer, and autumn delighted

The happy poet;

From winter the mound has finally sheltered him.

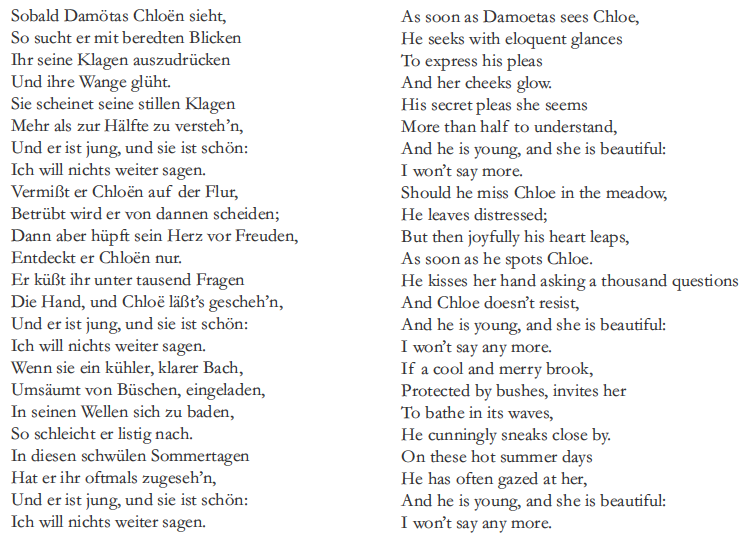

Die Verschweigung by Mozart

When I was arranging Lehmann’s interview for my New York radio program’s 85th Birthday Special, I suggested a Mozart aria and a Lied, but she asked me not to play any Mozart. She didn’t feel that she had done him justice. The historical awareness had arrived and Lehmann probably didn’t think her style was appropriate. In any case, she sang Die Verschweigung (Concealment) with great joy. The text by Christian Weisse (1726-1804) appealed to her sense of fun and sexiness. A strophic and tuneful Mozart song, its little jest at the end of every strophe provides Lehmann with the opportunity to make each suggestive in its own way. This, accomplished on February 27, 1949 (her 61st birthday), is yet another example of her acting genius. Notice the audience appreciation. Lehmann’s earlier (1935) studio recording with Ernö Balogh sounds fresh and younger than her 47 years.

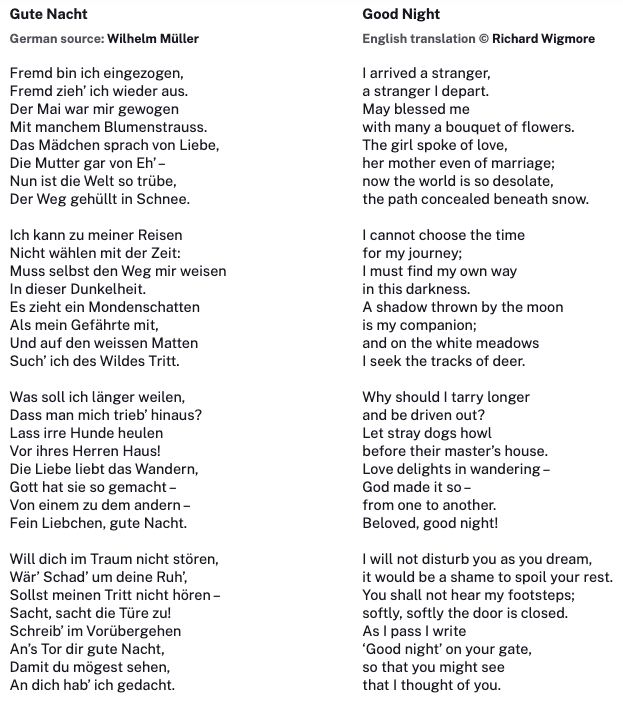

Two Songs from Winterreise by Schubert

Lotte Lehmann was the first woman to perform and record the complete Winterreise of Schubert. The recording was split between RCA and Columbia during 1940 and 1941. The pianist for the whole project was Paul Ulanowsky. Lehmann wrote the following about Lieder in general, which she feels: “[welds] words and music with equal feeling into one whole, so that the poet sings and the composer becomes poet, and two arts are born anew as one.” These words of hers are readily apparent in any excerpt that we hear from Winterreise. And we have two Winterreise excerpts from a radio broadcast of Lehmann’s New York Town Hall recital of February 11, 1951. I have left in the audience applause at the beginning to remind us of Lehmann’s esteem. The broadcast was preserved on wire (tape recording was in its infancy) and so there is some pitch instability, but otherwise the sound is excellent. Der Wegweiser was recorded for RCA on February 20, 1940 and Gute Nacht for Columbia in March 1941.