Must everything great singers record be great? We are interested in a broad range of their performances because we want to discover as much about their talent as possible.

Lotte Lehmann seldom fails. Her enthusiasm, commitment, and ardor come across in spite of the limitations of the original recording. In these “live” recordings you’ll notice that Lehmann sometimes becomes excited and, not having the words in her hands, changes the texts and improvises. She was, after all, also a poet so this wasn’t difficult for her.

The autumn of Lehmann’s life found her an important Lieder singer in the States. She set/broke records for her Town Hall appearances and sang throughout the country as well as in Canada and Australia.

The following Lieder are all from radio broadcasts of the 1940s, most of them from New York’s Town Hall. There was a single microphone, but instead of it being placed in front of her face as was done in commercial recordings, it tended to be lower and able to record more of the piano part.

In the 1940s some American critics found that her basic sound, the “golden” tones, were no longer present. That may be somewhat true, but the sound that remained seems more human because of age limitations that also made her work harder, just to sing! That very effort adds to the immediacy and emotion that she found in the words and that we notice. Her enthusiasm is so invigorating that I always smile while listening.

Lehmann is justly famous for some rather slow-moving songs. Allerseelen, Zueignung, Leise flehen, Der Nußbaum, Verborgenheit, and Der Tod das ist die kühle Nacht come to mind. Except for Der Wanderer, these seven songs below move along quickly. With this increase in speed you’ll hear that Lehmann is more evidently working to enunciate each word, fill it full of tone and meaning, move swiftly to the next word and load that one with emotion, special flavor, or change of color.

Don’t try to listen to more than a few of these tracks at once, for Lehmann’s intensity can be overwhelming. Instead, listen to a bit at a time, and notice what she does that is unique to her. Not that she tried to be unique! The care that Lehmann give to words, phrases, and meanings all came spontaneously to her.

These radio performances are available thanks to Lehmann fans who recorded the broadcast onto their own acetate discs at their homes. It is thanks to them, rather than the radio stations or networks, that we have these precious documents. Lani Spahr is the present-day sound transfer specialist who eliminated static and other extraneous noise.

A few words about the repertoire. When we remember that the radio performances in this set were broadcast in the U.S. after Hitler came to power, before, during, and after World War II, one can assume a degree of hesitancy towards an “all German program.” But generally, Lieder, even during the war, were accepted, in spite of the Nazis, thanks to the great poets and composers of Germany and Austria as well as Lehmann’s natural affinity and advocacy. As an American, I’ve always taken it as a matter of pride that Lehmann was allowed to sing so many Lieder at the time, and that some of these live performances were distributed on the same Voice of America 16-inch discs that served up Bing Crosby and the Andrew Sisters to the Armed Forces.

I’ve chosen to present these Lehmann rarities in chronological order of performance. Paul Ulanowsky is the pianist.

Heimkehr vom Feste (Returning Home from the Banquet)

Text: Heinrich Seidel (1842-1906)

Music: Leo Blech (1871-1958) Op. 21, No. 7

Recording: From a 1938 recital.

This light-hearted song will be new to most Lieder-Lovers. Perhaps too much a “trifle”, it doesn’t appear on today’s recitals or even on recordings from the past. So much the sadder!

Blech was a conductor by trade, and a personal friend of Lehmann. She often sang this song as a “final” encore. She’d sung it as early as 1920 on a program with other soloists in the Großer Saal (Great Hall) of the Vienna Philharmonic, and tried to record it in 1926. So it may come as no surprise to find it as an encore on the 1938 Town Hall recital of Wolf songs. Lehmann’s story-telling and her own fun with the fanciful song are infectious.

Bei Goldhähnchens war ich heut zu Gast,

Sie wohnen im grünen Fichtenpalast,

In einem Nestchen klein,

Sehr niedlich und sehr fein.

Was hat es gegeben? Schmetterlingsei,

Und Mückensalat und Gritzenbrei,

Und Käferbraten famos,

Zwei Millimeter groß.

Dann sang Vater Goldhähnchen was,

So zierlich klang’s wie gesponnenes Glas.

Dann wurden die Kinder beseh’n;

Sehr niedlich alle zehn.

Dann sagt’ ich “Adieu” und “Ich danke sehr!”

Sie sprachen: “O bitte, wir hatten die Ehr,

Es hat uns mächtig gefreut!”

Es sind doch reizende Leut!

At the Gold-crested Wrens I was guest today,

They live in a green spruce palace,

In a cozy little nest,

Very cute and very fine.

What was for dinner? Butterfly eggs,

And salad of gnats with beetle-leg puree,

And splendid roasted bugs,

Two millimeters in size.

Then Father Wren sang for us,

As delicately sounding as spun glass.

Then we looked at the little ones;

Very appealing all ten.

Then I said “Adieu” and “Thanks so much!”

They replied: “Oh please, it was our honor,

It has pleased us mightily!”

They’re charming people indeed!

Neue Liebe (New Love) (In dem Mondenschein)

Text: Heine

Music: Felix Mendelssohn Op. 19 No. 4

Recording: This is from a 1941 recital.

Mendelssohn is in his pixie mood, except for the last lines, when it becomes mysterious and other worldly for a bit. Lehmann and Ulanowsky take this at breakneck speed, and their effort captures the thrill of the riding elves. When the mystical last lines occur, Lehmann’s voice darkens to invoke the portentous words.

In dem Mondenschein in Walde,

Sah ich jüngst die Elfen reiten;

Ihre Hörner hört ich klingen,

Ihre Glöcklein hört ich läuten.

Ihre weißen Rößlein trugen

Güldnes Hirschgeweih und flogen

Rasch dahin, wie wilde Schwäne

Kam es durch die Luft gezogen.

Lächelnd nickte mir die Köngin,

Lächelnd, im Vorüberreiten.

Galt das meiner neuen Liebe,

Oder soll es Tod bedeuten?

In the moonlit forest

I watched the elves riding;

I heard their horns sound

I heard their bells ring.

Their white horses, with

Golden antlers, flew on

Swiftly, like wild swans

Traveling through the air.

Smiling, the queen nodded at me,

Smiling, as she rode overhead.

Was it because of my new love,

Or does it mean death?

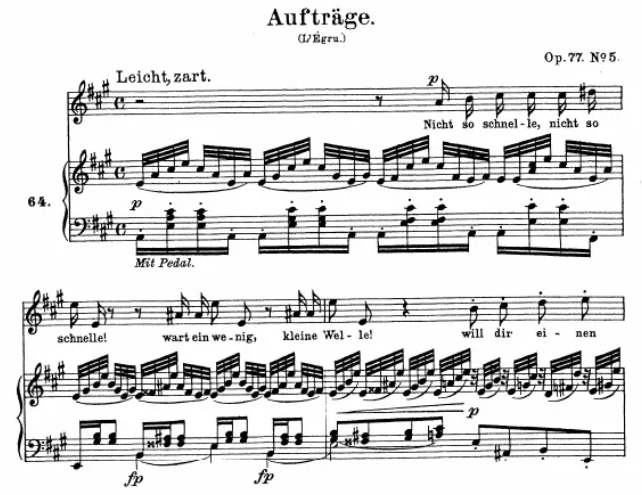

Aufträge (Messages) (Nicht so schnelle)

Text: Christian L’Egru (1809-1850)

Music: Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Op. 77 No. 5

Recording: From a 1946 recital

Though Lehmann recorded Aufträge with Ulanowsky for Columbia on 26 June 1941, it was not released as a 78rpm, but was published on Columbia LP ML 5778. This present recording is a “live” performance from 1946.

There are a lot of notes for the pianist and a lot of words for the singer: Lehmann and Ulanowsky make the most of their tasks. Whether ripples in the brook or the flight of a dove, we are witnesses to it all. And listen to the fermata that Lehmann beautifully sings on the “du” at the end.

Meredith Gailey writes: Even though the compositions that Schumann wrote in 1850 were beginning to show signs of his mental deterioration, Aufträge, written in April of that year, demonstrates that he was still capable of placing immense technical demands on the pianist in his songs. Possessing virtuosic vitality, the piece not only stretches the pianist’s expertise, but it also demands facile articulation of the vocalist. This light, rapid, playful work is a satisfying setting of L’Egru’s text. Its thrice-repeated vocal sections are supported by staccato beats in the left hand and cascading thirty-second notes in the right. The words tell of a young man’s attempt to send tender messages of love to his sweetheart through a wave, a dove, and the moon.

Nicht so schnelle, nicht so schnelle!

Wart ein wenig, kleine Welle!

Will dir einen Auftrag geben

An die Liebste mein.

Wirst du ihr vorüberschweben,

Grüße sie mir fein!

Sag, ich wäre mitgekommen,

Auf dir selbst herabgeschwommen:

Für den Gruß einen Kuß

Kühn mir zu erbitten,

Doch der Zeit Dringlichkeit

Hätt’ es nicht gelitten.

Nicht so eillig! halt! erlaube,

Kleine, leichtbeschwingte Taube!

Habe dir was aufzutragen

An die Liebste mein!

Sollst ihr tausend Grüße sagen,

Hundert obendrein.

Sag, ich wär’ mit dir geflogen,

Über Berg und Strom gezogen:

Für den Gruß einen Kuß

Kühn mir zu erbitten,

Doch der Zeit Dringlichkeit

Hätt’ es nicht gelitten.

Warte nicht, daß ich dich treibe,

O du träge Mondesscheibe!

Weisst’s ja, was ich dir befohlen

Für die Liebste mein:

Durch das Fensterchen verstohlen

Grüße sie mir fein!

Sag, ich wär auf dich gestiegen,

Selber zu ihr hinzufliegen;

Für den Gruß einen Kuss

Kühn mir zu erbitten,

Du seist schuld, Ungeduld

Hätt mich nicht gelitten.

Not so fast, not so fast!

Wait a moment, little wave!

I’ve a message to give you

For my sweetheart.

If you glide past her,

Greet her fondly!

Say I’d have come too,

Sailing on your back:

And would have boldly

Begged a kiss for my greeting,

But pressing time

Did not allow it.

Not so fast! Stop! Allow me,

Little light-winged dove,

To entrust you with something

For my sweetheart!

Give her a thousand greetings,

And a hundred more.

Say, I’d have flown with you

Over mountain and river:

And would have boldly

Begged a kiss for my greeting,

But pressing time

Did not allow it.

Don’t wait for me to drive you on,

You lazy old moon!

You know what I ordered you to do

For my sweetheart:

Peep secretly through the window-pane

And give her my love!

Say, I’d have climbed on you

And flown to her in person;

And would have boldly

Begged a kiss for my greeting,

It’s your fault, impatience

Would not permit me.

Auflösung (Dissolution)

Text: Johann Mayrhofer (1787-1836)

Music: Schubert D. 807

Recording: From a recital of 1946.

Mayrhofer’s poem is not easy to understand. Here is one idea of its meaning: Everything comes together; everything falls apart. Things are resolved; things dissolve. This is the paradox inherent in the word ‘Auflösung’, which could be resolution or dissolution, fulfillment or destruction. And yet, for Mayrhofer, this is a ‘consummation devoutly to be wish’d’.

He begins with immolation. The poet feels his body sizzling with fires that will out-blaze the sun itself. He is entering into a state in which external beauty (in the form of music or the power of nature at springtime) has no more role to play, such is the character of the apotheosis that is taking place. Everything is collapsing in on itself and on him.

Or rather, powers are welling up from within him that are beginning to overwhelm him. Left alone, he is in the presence of multitudes. As music falls silent, the choirs of heaven resound. Immolation and cataclysm have revealed themselves to be orgasm. It all wells up from the hidden recesses within him and releases him into the ether. Some traditions call an orgasm a ‘little death’, but there is nothing ‘little’ about the death being welcomed and invoked in this poem. It is as if the riddle of the universe itself is being resolved in this ultimate dissolution.

Lehmann summons up, at the age of 58, all her considerable Wagnerian strengths, to sing one of the most powerful performances one can hear of this demanding song. The final mutterings in her lowest register sound something between threatening and fearful.

Verbirg dich, Sonne,

Denn die Gluten der Wonne

Versengen mein Gebein;

Verstummet, Töne,

Frühlings Schöne

Flüchte dich, und laß mich allein!

Quillen doch aus allen Falten

Meiner Seele liebliche Gewalten;

Die mich umschlingen,

Himmlisch singen.

Geh’ unter, Welt, und störe

Nimmer die süßen, ätherischen Chöre.

Hide yourself, sun,

For the glow of bliss

Burns my entire being;

Be silent, sounds,

Spring beauty

Flee and leave me alone!

Welling up from every recess

Of my soul are pleasing powers;

That envelop me,

With heavenly singing.

Dissolve, world, and never disturb

The sweet, ethereal choirs again.

Der Wanderer (The Wanderer) (Des Fremdlings Abendlied)

Text: Georg Philipp Schmidt von Lübeck (1766-1849)

Music: Schubert D. 489

Recording: From a 1946 recital.

Der Wanderer is among the greatest of Schubert’s Lieder. It was one of the few songs that was successful in his own lifetime and is found in his technically demanding Wanderer Fantasy (Fantasy in C major) for piano. This deeply felt Lehmann performance, a radio broadcast from the stage of New York’s Town Hall, eclipses for me all other performances. The words receive a high level of understanding and acting genius from Lehmann, and the completely unified support for her interpretation by Ulanowsky offers us a Gesamtkunstwerk for all time.

Here is some background information on the whole song: The song begins with a recitative, describing the setting: mountains, a steamy valley, the roaring sea. The wanderer is strolling quietly, unhappily, and asks, sighing: “where?” The next section, consisting of 8 bars of a slow melody sung pianissimo, describes the feelings of the wanderer: the sun seems cold, the blossoms withered, life old. The wanderer expresses the conviction of being a stranger everywhere. This 8-bar section was later used by Schubert as the theme on which his Wanderer Fantasy is based. Next the music shifts to the key of E major, the tempo increases and the time signature changes to 6/8. The wanderer asks: “where are you my beloved land?” The place he longs for is green with hope, “the land where my roses bloom, my friends stroll, my dead rise” and, finally, “the land which speaks my language, Oh land, where are you?” Towards the end of this section, the music gets quite animated and forms the climax of the song. Finally, the music returns to the original minor key and slow tempo. After quoting the question “where?” from the opening, the song closes with a “ghostly breath” finally answering the question: “There where you are not, there is happiness.”

Ich komme vom Gebirge her,

Es dampft das Tal, es braust das Meer.

Ich wandle still, bin wenig froh,

Und immer fragt der Seufzer, wo?

Die Sonne dünkt mich hier so kalt,

Die Blüte welk, das Leben alt,

Und was sie reden, leerer Schall,

Ich bin ein Fremdling überall.

Wo bist du, mein geliebtes Land?

Gesucht, geahnt, und nie gekannt!

Das Land, das Land so hoffnungsgrün,

Das Land, wo meine Leute gehn.

Wo meine Freunde wandelnd gehn,

Wo meine Toten auferstehn,

Das Land, das meine Sprache spricht,

O Land, wo bist du?

Ich wandle still, bin wenig froh,

Und immer fragt der Seufzer: wo?

Im Geisterhauch tönt’s mir zurück:

“Dort, wo du nicht bist, dort ist das Glück!”

I come from the mountains,

The valley steams, the sea roars.

I wander silently and seldom happy,

And my sighs always ask “Where?”

The sun seems so cold to me here,

The flowers faded, the life old,

And what they say, empty noise,

I am a stranger everywhere.

Where are you, my dear land?

Sought, dreamed of, yet never known!

The land, so green with hope,

The land, where my people walk.

Where my friends wander,

Where my dead ones rise,

The land that speaks my language,

Oh land, where are you?

I wander silently and seldom happy,

And my sighs always ask “Where?”

In a ghostly breath the answer comes:

“There, where you are not, there is happiness.”

Neue Liebe, neues Leben (New Love, New Life)

Text: Goethe

Music: Beethoven Op. 75 No. 2

Recording: Lehmann and Ulanowsky performed this in 1948.

Despite her 60 years, one hears Lehmann really excited to tell us of the intense emotions of love, and in this particular song, new life. At her tempo, the rapid accompaniment sounds almost unplayable, but somehow Ulanowsky manages it. Lehmann never recorded this in a studio, so this live performance is especially important and in its day preserved in an extra way because it was distributed by the Armed Forces Radio Service and VOA.

Here’s some background on Goethe’s poem: It begins with two rhetorical questions in the first two verses. The first word “heart” in verse 1 – like the title – suggests that this is a poem that has love as its central object of contemplation. In verse two, the verb “betäubt” makes it clear that his heart is not in a happy mood. He speaks to his heart and personifies it by asking it many questions. This is followed by an initial explanation for the state the heart is in, a “strange, new life” (verse 3). The next verse reinforces the impression that the heart is “betäubt”. For with the “heart” in the first verse, Goethe means himself. The questions he asks his heart he should actually be asking himself. The fourth verse, “I no longer recognize you,” underlines that there has been a change in his life that plunges Goethe into conflict and inner contradictions. In contrast to the remaining verses, which are all written in the present tense, verses five and six are written in the past tense. For it is a “flashback,” describing everything that is “gone” as a result of the new love. Even the “diligence” and “peace” (verse 7) are now gone. The sigh “Ah” in the eighth verse makes it clear how much Goethe regrets this loss.

At this point it makes sense to explain Goethe’s biographical background. When he met the banker’s daughter Lilli Schönemann in Frankfurt in 1775 and became engaged to her, this resulted in the relationship being rejected by both families. Goethe soon felt constrained by this love: the connection across social classes. After six months he broke off the engagement.

Verses 5 to 7 represent Goethe’s old life, which was now completely changed. The engagement to a member of the upper class also explains why the poem, rather untypical for the Sturm und Drang era, has a uniform rhyme scheme, orderly cadences and does not contain any ravings that are completely detached from reality. In the second stanza, Goethe continues to address the heart. The verb “to bind” shows that the heart’s bond with its beloved is overwhelming. The rhetorical question is asked over four verses, which is probably intended to get to the bottom of the reason for this bond, the bond that seems so involuntary and unhappy. The “bloom of youth” (line 9) as a possible cause, i.e. Lilli’s probably quite young age, is mentioned, as is her “lovely figure” (line 10), and her “look full of loyalty and kindness” (line 11). This positive description of his Lilli stands in contrast to the expression “bound with infinite force” (lines 9 and 12). Goethe seems to have no influence on love, nor does he seem to agree with it.

Herz, mein Herz, was soll das geben?

Was bedränget dich so sehr?

Welch ein fremdes neues Leben!

Ich erkenne dich nicht mehr.

Weg ist alles, was du liebtest,

Weg, warum du dich betrübtest,

Weg dein Fleiß und deine Ruh’ –

Ach, wie kamst du nur dazu!

Fesselt dich die Jugendblüte,

Diese liebliche Gestalt,

Dieser Blick voll Treu und Güte

Mit unendlicher Gewalt?

Will ich rasch mich ihr entziehen,

Mich ermannen, ihr entfliehen,

Führet mich im Augenblick,

Ach, mein Weg zu ihr zurück.

Und an diesem Zauberfädchen,

Das sich nicht zerreissen läßt,

Hält das liebe, lose Mädchen

Mich so wider Willen fest;

Muß in ihrem Zauberkreise

Leben nun auf ihre Weise.

Die Verändrung, ach wie groß!

Liebe! Liebe! Laß mich los!

Heart, my heart, what does this mean?

What is besieging you so?

What a strange new life!

I don’t know you any longer.

Gone is all that you loved,

Gone is what troubled you,

Gone is your diligence and peace–

Alas! how did you come to this!

Does youthful bloom shackle you,

Of this lovely figure,

Whose gaze is full of truth and goodness

With endless power?

If I rush to escape her,

To take heart and flee her,

I am led in a moment,

Alas, back to her.

And with this magic thread,

That cannot be ripped,

The dear, mischievous maiden

Holds me fast against my will;

In her magic circle I must

Live now in her way.

The change, alas – how great!

Love! Love! Let me free!

Wie froh und frisch (How Happy and Fresh)

Text: Johann Ludwig Tieck (1773-1853)

Music: Brahms Op. 33 No. 14 [Magelone Lieder]

Recording: From a 1949 recital.

This is the point in the cycle of songs where the hero’s boat is saved and he rejoices. The piano part mirrors the storm-driven waves. Lehmann, in her excitement, changes and forgets many words, but keeps the sweep of the song intact. She fills the appropriate moments with exhilaration and eagerness. One can witness that Brahms was more interested the music than the words when you hear how he crams “ihr wankender Wogen” in such a short space of time. But there are still moments when there’s time to enjoy Tieck’s poetry.

Wie froh und frisch mein Sinn sich hebt,

Zurück bleibt alles Bangen,

Die Brust mit neuem Mute strebt,

Erwacht ein neu Verlangen.

Die Sterne spiegeln sich im Meer,

Und golden glänzt die Flut.

Ich rannte taumelnd hin und her,

Und war nicht schlimm, nicht gut.

Doch niedergezogen

Sind Zweifel und schwankender Sinn;

O führt mich, ihr wankender Wogen,

Zur lang ersehnten Heimat hin.

In lieber, dämmernder Ferne,

Dort rufen heimische Lieder,

Aus jeglichem Sterne

Blickt sie mit sanftem Auge nieder.

Ebne dich, du treue Welle,

Führe mich auf fernen Wegen

Zu der heissgeliebten Schwelle,

Endlich meinem Glück entgegen!

How happy and fresh my spirits soar,

Behind me I leave all my fears,

My heart strives with new courage,

And new yearnings awaken.

The stars are mirrored in the sea,

And golden shines the tide.

I ran dizzily back and forth,

And was neither bad nor good.

But laid low

Are doubts and hesitant thoughts;

Oh carry me, you rocking waves,

To the homeland I have so long yearned for.

In the dear, darkening distance,

There call the songs of home,

From every star

She gazes down with gentle eyes.

Be calm, you trusty wave,

Lead me on the distant paths

To that well-beloved threshold,

At last to my happiness!