Chapter 1 My Whole FamDamly

Whole FamDamly! and there weren’t that many to account for. My mother didn’t have siblings. Her mother was the only family member that I loved. We called her Nana and everyone else said Silver (my father had once noticed her up on the boardwalk with her white hair and called out “Hi, ho Silver” and it took). Her given name was actually Grace. My Uncle Bob was an only child. His father, Arthur, hardly recognized the existence of my father, this having to do with the first born inheriting the English throne. And my father hated his father (who he didn’t recognize when he returned after WW I). Till his dying day he didn’t believe Arthur was his real father!

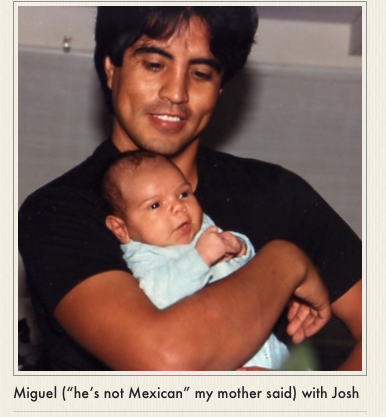

My mother shouldn’t have had kids. I didn’t find this out until she was dead and my father told me that she hadn’t wanted any. After three years of marriage he talked her into having me and then he wanted a sibling for me. He thought of the good times he’d had with his brother Bob. The less said about my mother, the better. I’ve always tried to think of good things, but they were stuff like: she kept the house clean; she cooked meals for us; she shopped for food (we didn’t have enough money for her to engage in “shopping” as a sport, if she’d wanted to). She loved her art and took classes in which she painted after the example of the teacher. Nothing original, but nothing bad either. She was completely self-centered. And honest. She was prejudiced about every group that WASPs hate, but didn’t see that our long-time salesman at Alameda Thrift, Lenard [sic] was black, that my pal from Mexico, Miguel was Hispanic or that her cruise friends were Jewish. Selective hate. She “taught” Steve and me by negative example. We often said that when we grew up we wanted to be nothing like our mother, conscious even then of her mean spirit. So in a way, I owe my happy life to my mother’s influence, even if it was a negative one.

One of our favorite stories about Mom was one that should have mortified her, but she didn’t get the point. Miguel was visiting, and as usual, he’d stopped to admire Mom’s paintings. We’d stopped the praise and there weren’t many guests, so Mom loved Miguel’s favorable words. She knew he was an artist, so his words held special power. During the lunch that followed, she somehow got on the subject of Mexicans: “those dirty, lazy, lying guys.” My father was embarrassed and quietly pointing towards Miguel, whispered “You know Miguel’s Mexican.” With an indignity in her tone, she replied, “NO, he isn’t!” Miguel and I still laugh at that and he always says, “She was so innocent.”

My mother was prudish: she never swore and there were words that she didn’t want spoken around her. “Subpoena” included a sound that she wanted to avoid hearing. When we were infants we were taught words that no one else used: dum dum, dee dee, donicker and poot. It was embarrassing to learn that these were baby words that none of our pals used. No four-letter-words in our house!

My mother’s middle name was Gould. It was her con-man father’s idea to include it and then write to the heirs of the Gould fortune to let them know, hoping that they’d send thousands of dollars. Mom had nothing to do with this of course, and told us the story to further denigrate her father, who had been divorced by my grandmother long before we came along. Silver/Grace/Nana never remarried; this at a time when a single woman was a rarity. She had to take jobs such as a kind of housekeeper, living where she worked. Or a Nanny to a bunch of ornery kids.

On the positive side, my mother shared her love for art with Steve and me. One of my earliest memories is going to the Los Angeles Art Museum which, at that time wasn’t far from our Inglewood home. We were probably too young to appreciate the paintings and sculptures, but it initiated in me my lifelong love of museums. When I was at UCLA and hoping to share my love of music with my folks, my mother said, “I don’t try to make you love art, so why do you try to make us love music?” I told her then how much her love of art had broadened and enriched my life and that I was glad that she’d shown Steve and me simple water color techniques and how to do Christmas cards using a carved linoleum block. She still wasn’t persuaded to open her ears to music. One Christmas they bought me the LP of the Mikado and I immediately played it and they seemed to enjoy the overture, but when singing began, my mother made an ugly face and left the room. As I said earlier about her, she was honest to a fault.

My mother wasn’t reticent to tell negative stories about herself. When she was a cute little girl one of her least favorite uncles (there were many) was visiting and she said over and over to him “See the pretty pocket?” until he got down close to her dress and she kneed him in the nose.

When someone said something about learning Spanish, she had the automatic reaction of reciting a Spanish-language poem that she’d memorized, “Terezita Mia.” If someone mentioned something in German, she’d repeat something that she’d shouted at Steve and me when we were children and she wanted us to do something immediately. It was something that her father said was German for “right about face forward march.” It sounded like “Wasch mit ein Hausgätlings Sumpf.” If a French word was mentioned, then she brought the conversation’s attention back to her with a word that she knew, which was ‘finette’, the name we gave our second dog, the toy poodle. She was completely unaware that no matter what anyone said, she always wanted the focus to be on Helen. It was embarrassing when I was old enough to notice.

Mom was jealous of our neighbor mothers in La Cañada. She’d ask if they were prettier, or nicer and once after we had a summer breakfast in the park, if Nina’s pancakes were better than hers, “please, tell me honestly”. With a real reluctance Steve and I allowed that Nina’s pancakes were more tasty. Big mistake! She was upset about that for years.

One of my mother’s ways of getting her way was to cry. My father used to say that she’d cry when the stoplight turned red. Of course such a frequent device lost its effectiveness. She gave me a very nice Christmas present once, and I guess, though I was pleased, I didn’t make it obvious enough and she began to cry.

I said I was going to stay positive about my mother, but I do have another of Mom’s quirks to share. When she drove the car, she aimed the hood ornament on the line on the street, even on the freeway. She’d ask us why everyone was honking and we’d tell her, but seconds later she was on the line.

I do have a funny story to tell about my mother’s father Jack; perhaps it helps our understanding of her adult personality. Jack and Grace had divorced in the 1920s when such a thing was rare. He was a philanderer and a con-artist. My mother told embarrassing tales of being in a restaurant when her father would recognize someone he’d conned, cover his face with his hat and exit as fast as possible with his family in tow. Another story that she told was of Jack taking her to a big department store where little Helen was encouraged to pick out all the most beautiful clothes, shoes, etc. After they were all delivered to their house and she was beginning to enjoy them, a representative of the store arrived to collect every bit of the treasures because they weren’t paid for. Jack was actually caught when he was running his Grocetaria (in which people went around the small market with a small basket over their arm and picked out things for themselves instead of having a clerk serve them). He displayed a rather large doll that walked and talked and was offered as a prize if you put so many of the coupons together that actually, like a picture puzzle, made up the doll. Of course Jack left off the final puzzle piece so he never had to present the doll to a customer. Evidently the law caught up with him on this one and he had to leave that state. He was wanted in many, so I guess he wasn’t a very good con-man.

The last years of my mother’s life were clouded by Alzheimer’s when she became passive, and actually nicer than she’d ever been before. The night before she died (of a kind of brain seizure) she and I played the game she’d taught Steve and me where we’d draw a scribble and the other would make something out of it. Her last drawing was a kind of devil with a beard.

In the morning my father shouted out that she’d fallen and he couldn’t help her. I found her flat on the floor and immediately called 911 which brought the firemen and led me through CPR. When the first responders arrived they hooked up sensors to her brain and I could see a flat line, which they didn’t share with us. When, after a solemn breakfast together, my father and I reached the hospital they took us into a small room and told us that she’d died. My father cursed and hit the walls with his fist and said that she was a good person, etc.

Her funeral service was rather bizarre; my father was frozen stiff and silent with grief so I ran the whole thing. Since a large contingent of the thrift store workers were in attendance I said everything twice: second time in Spanish. When I asked if anyone wanted to share a Helen-memory there was a kind of embarrassing silence. Her friend from their mutual girlhoods, June Douglas (nee Willibrandt) came up and after a bit of ramble said: “Helen, we’ll miss you!” Mom’s cousin, Jim Ackerman told a story about how she’d helped him complete a school project on the color wheel (of course over 70 years prior!). One of the workers at the adult care center, where she’d spent many days in the last year, told of mom kindly helping her fellow adults with their art projects.

You can enjoy some of my mother’s art works on the following page. She hadn’t painted in years, but when Steve and I were teenagers and out of the house and more independent, Mom started taking classes that respected painters offered. It seemed that the student-painters in those classes were middle aged or older and mostly women. June, one of her childhood friends, who was also an artist often joined the classes. Mom’s Art