From Beaumont Glass’ biography, Lotte Lehmann: A Life In Opera & Song, Chapter 9

She Was His Birthday Present

Lotte Lehmann met Otto Krause, her handsome future husband, in a most unusual way: she was his birthday present. A present from his wealthy wife, who wanted something very special for that special occasion. He was a great opera-lover and his favorite singer was Lotte Lehmann. His wife, for whom money was no object, gave a splendid party and engaged Fräulein Lehmann to sing. For Lotte, it was love at first sight. She had never experienced that feeling so overwhelmingly before. Every note she sang became a billet doux. The recipient was just as smitten as the gift. He left his wife and—temporarily—his four children. The first Mrs. Krause deeply regretted her generous, extravagant impulse, which had turned out to be much more expensive than she had ever dreamed. One can understand her bitterness; but she rather overdid her fury as a woman scorned. She adamantly refused to give Otto a divorce and began to make Lotte’s life as miserable as possible. Since she was very rich and influential, she could afford to make Lotte very miserable indeed. Colleagues shunned her. Someone wrote “Whore” in red chalk on her dressing room door. All Vienna was titillated by the scandal.

Lotte was torn apart by an ethical dilemma, a crisis of conscience, that would have been devastating enough as her private problem; it was unbearably aggravated by the merciless glare of unwanted publicity. She was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. She decided to leave Vienna and its opera. The following story appeared in the Neues Wiener Tagblatt of February 13, 1922:

…Frl. Lotte Lehmann yesterday submitted to the directors of the State Opera a request for release from her contract. We have been informed by competent authority that this decision is unrelated to any artistic matters or to the relationship between the artist and the directors of the State Opera, and is attributable only to private personal reasons. At present Frl. Lehmann is firmly determined to leave Vienna permanently….She is presently a patient at a sanatorium in the vicinity of Vienna, undergoing treatment for a nervous disturbance which developed out of entirely private causes.

The directors did not release her. She was at this point their most beloved star, especially now that Maria Jeritza was spending more and more of her time at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

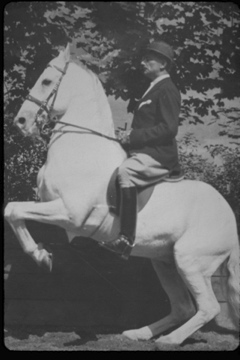

Otto had come to Vienna as a child from Budapest, where he was born in 1883. Before his marriage he had served as a cavalry officer, having been an accomplished horseman since the age of fourteen. Back in Vienna, Lotte had the thrill of seeing him ride one of the famous Lipizzaner, the white stallions of the Spanish Riding School, still one of the most popular tourist attractions in Austria. He taught Lotte to ride and some of their happiest times were when they were galloping together over windswept moors or through the shallow surf beside the sea.

He was not, however, a man of independent wealth.

It was four years before he was free, four years of trial, of passion and penitence, of private ups and downs, for Otto and Lotte.

In spite of his “job”—mostly honorary—with the insurance company, Otto had next to nothing of his own, and his children were accustomed to a certain degree of luxury. He and Lotte were two generous and expansive natures. They spent their money—which means her money—very freely. Concert managers negotiated fees and booked the dates and hotels; the artists themselves had to pay for everything, accompanist, travel with entourage (including pets), publicity, advertising, photographs, taxes, and agents’ percentages. In those days opera stars were expected to provide their own costumes and accessories. In America, especially, concert gowns had to be spectacular, and could never be worn twice in the same area. A famous prima donna had to stay at prestige hotels. Her wardrobe would be photographed, and discussed in the local papers. In Lotte’s case, she rarely traveled alone; whenever possible Otto was with her.

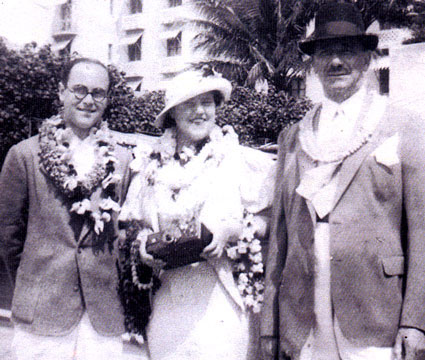

[On the return from the Australian tour of 1937]: From the cold of Tasmania to the tropical heat of Ceylon! From Port Said and Cairo to the Schnürlregen (drizzle) of Salzburg—the contrasts in climate were too much for Otto. Back in his beloved Austria he became feverish and very ill. Heavy smoking was hardly a help. He developed a persistent cough, and lost a lot of weight. His lungs were infected. His heart was not in order. Lotte was terribly alarmed; he had always seemed so robust, so athletic. By September it had become clear that he could not accompany her abroad, at least not for a while. The doctors demanded that he stay in bed; and when she had to leave for America, he was to go to a sanatorium in the mountains.

[Lehmann left for an American tour.] Otto, of course, had to stay behind, at the Semmering Sanatorium. Lotte hoped he would be well enough by Christmas to join her in New York. His daughter, Manon, would accompany him and stay for a visit, her first in America.

Otto, who had apparently recovered enough to risk the trip, had come over with Manon in time to spend Christmas with Lotte. Now he had to return immediately to try to settle the affairs of his children. They were half-Jewish, through their mother, and in very real danger, although no one realized yet the full enormity of what might lie ahead. Manon had to go with her father to Vienna, for legal reasons, before they could return to America as immigrants.

After fulfilling her American contracts, Lotte sailed for London, where she was engaged again, after two years, for the season at Covent Garden. The crossing was a rough one. Nature added an unwelcome contribution to the human cause for despair.

Meanwhile, Lotte pulled every string she could to find a way to get Otto’s children out of Austria.

Otto’s condition worsened. He was sent to a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland.

[Lehmann fainted with worry during an opera, but recovered the next day.] She was still desperately worried about Otto. The doctors in Davos reported that he had tuberculosis and that the treatment he had received in Austria had been completely wrong for him. That news, on top of the troubles of his children and the financial crash in Vienna, was devastating to Otto, and, of course, to Lotte too.

Otto’s position with the Viennese insurance company had been a rather vague one, an insubstantial title with little or no salary behind it, so that he would have an occupation on his passport, and an identity other than that of “Mr. Lehmann,” the opera singer’s husband. Now, in any case, even that shadow of a job was gone. For some time now, Lotte had been sending money regularly to his sister in Germany and other relatives. With her husband, her brother, and four stepchildren to support as well, Lotte’s financial burden was enormous. Now she asked her manager to arrange some concerts for her in America. It was a shock to her when he could only come up with two dates. It seemed better to see what could be done in Europe.

Meanwhile, Otto’s condition was getting critical again. Since he refused to go back to Davos, Lotte sent him with Manon to America in June, where he checked into a sanatorium at Lake Saranac, New York. Manon was instructed not to leave him alone. Lotte stayed behind, with her three stepsons.

[Lehmann wrote a friend the following]: “The doctors say he will get better. I can hardly believe that, when I look at him. He is the shadow of himself, so enervated, wretched, and weak. He has been lying in bed for eighteen weeks already. He still has to stay in bed for months. Imagine that. He is pitifully thin, there is always some fever, even though the terrible spitting of blood has stopped….He never wanted to believe he was sick. He was always vain about his health, proud of being a dashing, good-looking man….Both of his lungs are infected, though he does not know that yet….It is very hard for both of us that I can only be with him so seldom. I love him so much—never was I nearer to him than now, when he is so miserable. I mull over in my mind what I might be able to do to make him happier. But how can I help him?”

Between concert engagements, Lotte tried to be with Otto as much as possible, but she had to earn money to cover their enormous expenses. She worried about him constantly, and tried to make sure that there was always someone with him who spoke German, to keep him company; for Otto still spoke scarcely a word of English and was frightfully homesick for his lost fatherland. Lotte sent Marie, her maid, to Saranac to cook for him, because he longed for Austrian food.

Otto died on January 22, 1939.

Lotte was on tour when it happened. She was in Spokane when she heard the news that he had contracted pneumonia. Lotte immediately canceled her remaining concerts and tried to charter a plane. That was impossible, flying conditions were bad. There was a blizzard in the East. She took a train. Desperately she hoped to reach his side in time.

At Fargo, North Dakota, she was able to persuade officials of the Great Northern Railway to delay the train for fifteen minutes while she telephoned the sanatorium at Saranac.

The doctors called for Otto’s friends to be near him. Viola went first. Robin Douglas, her new husband, followed with Frances and Pucki. The roads were covered with ice. Robin could not drive her car, so Frances had to do all the driving during a long, exhausting night. First to Saranac, which they reached at 4 a.m. Then to Syracuse, to meet Lotte’s train. Viola and Pucki stayed with Otto. Driving conditions were indescribably harrowing. Giant billboards were blown from their moorings and flapped this way and that across the icy roads. From Syracuse Frances called Saranac; Viola told her that Otto was dead. Lotte, who had called from Toledo, had already heard the heart-breaking news. Callous photographers had actually tried to photograph her weeping. When her train reached Syracuse she cried out: “Peter!” He ran into the train, to join her, and suddenly it left the station with both of them on board. Frances and Robin headed back to Saranac through ice and snow.

For those who went through it, that was a night they would never forget.

The funeral took place under a tent, because of the weather. Among the floral tributes there was an arrangement of white carnations in the shape of Otto’s favorite horse, a Lipizzaner stallion.