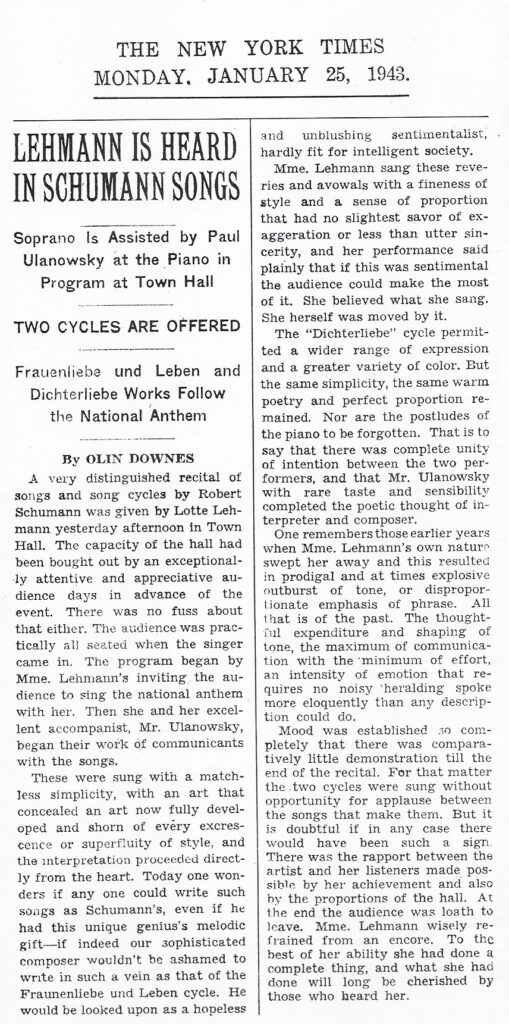

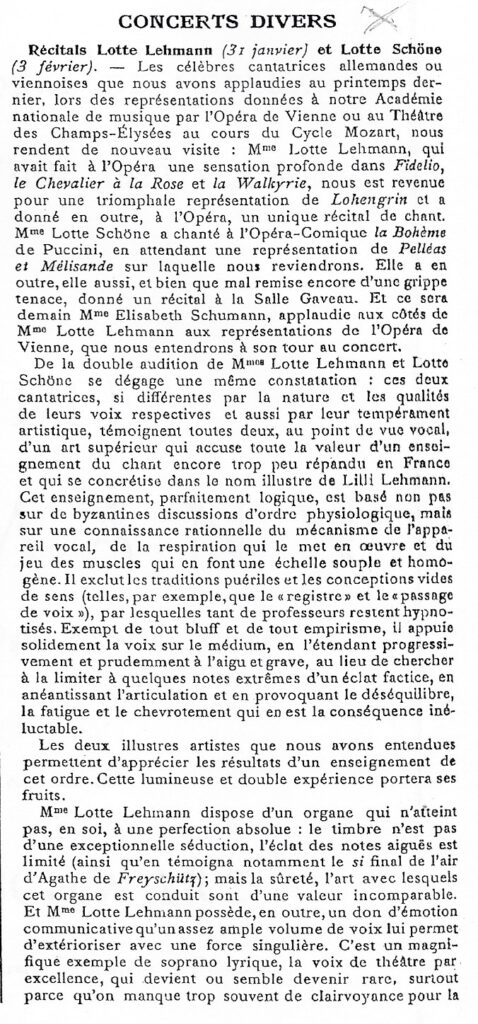

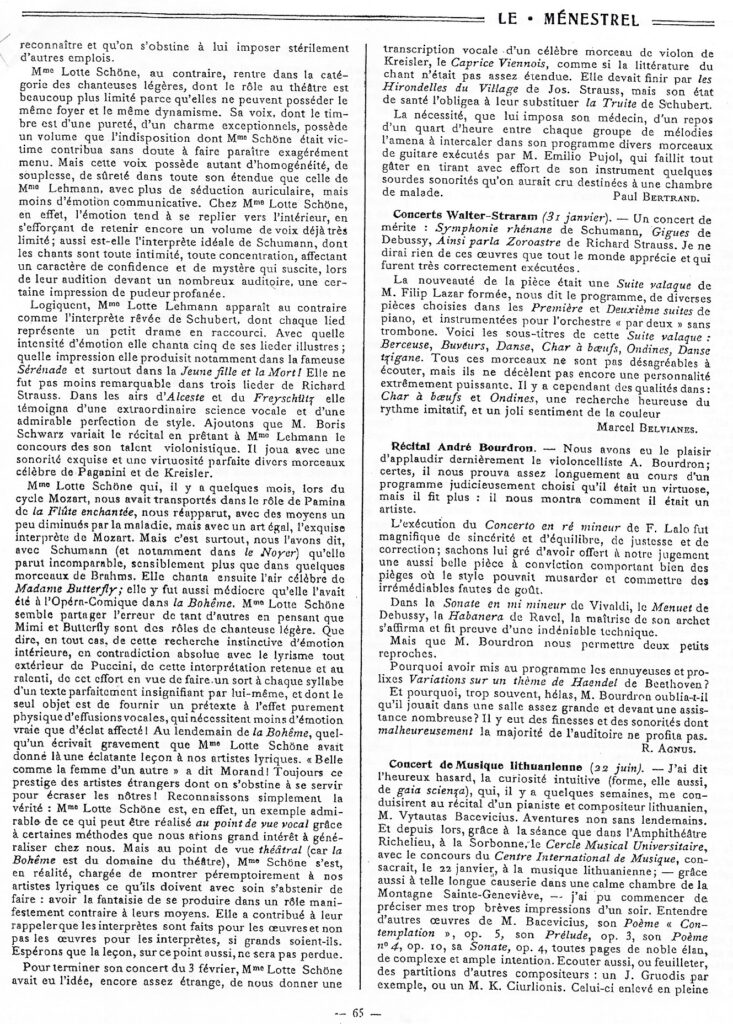

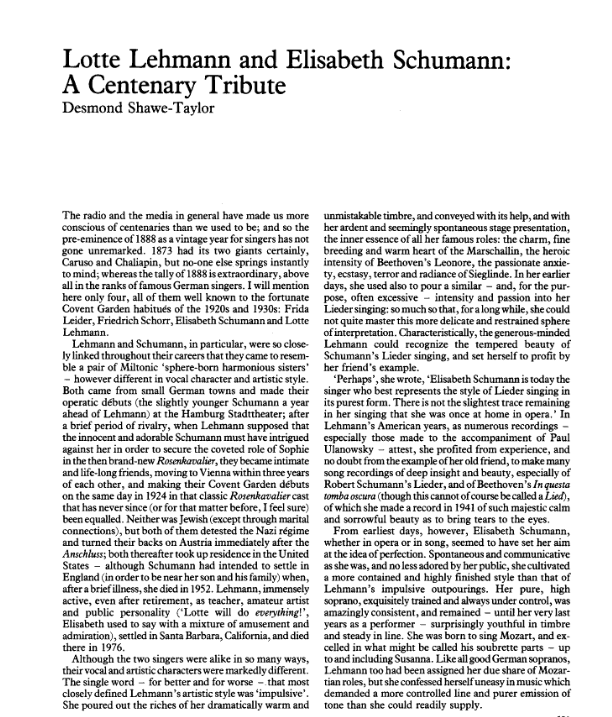

Here’s a review of the Lehmann Centennial held at UCSB in 1988.

Entertainment & Arts

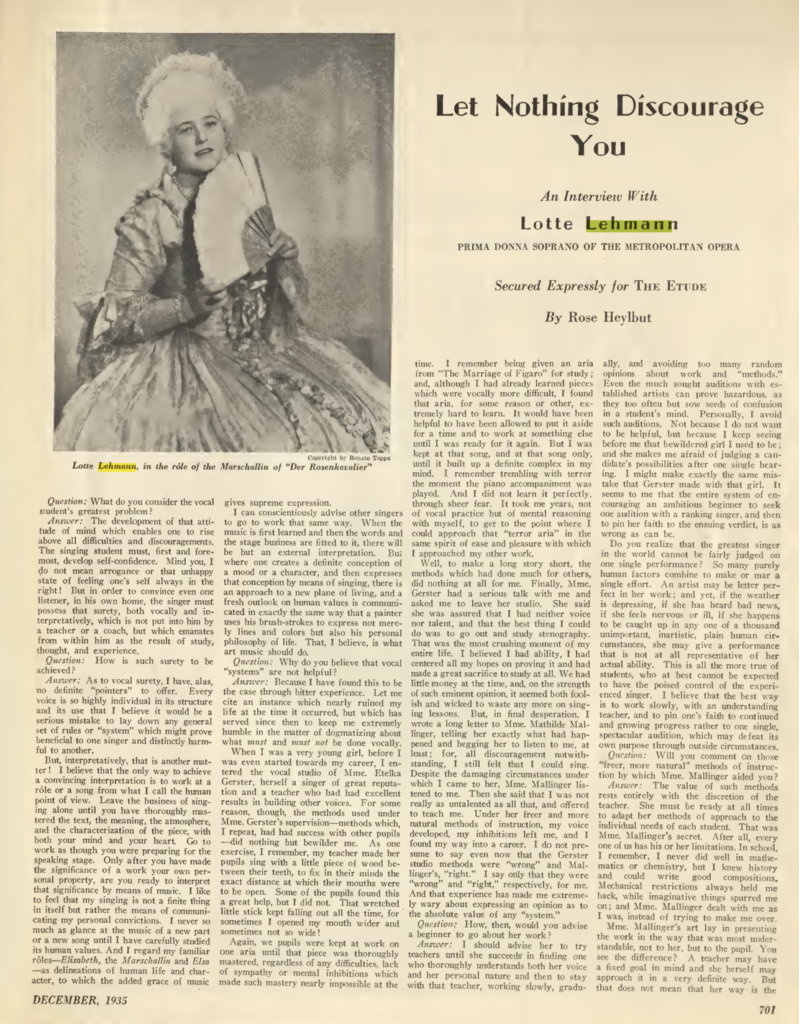

Centennial Celebration for a Singing Actress

By MARTIN BERNHEIMER

June 5, 1988 12 AM PT

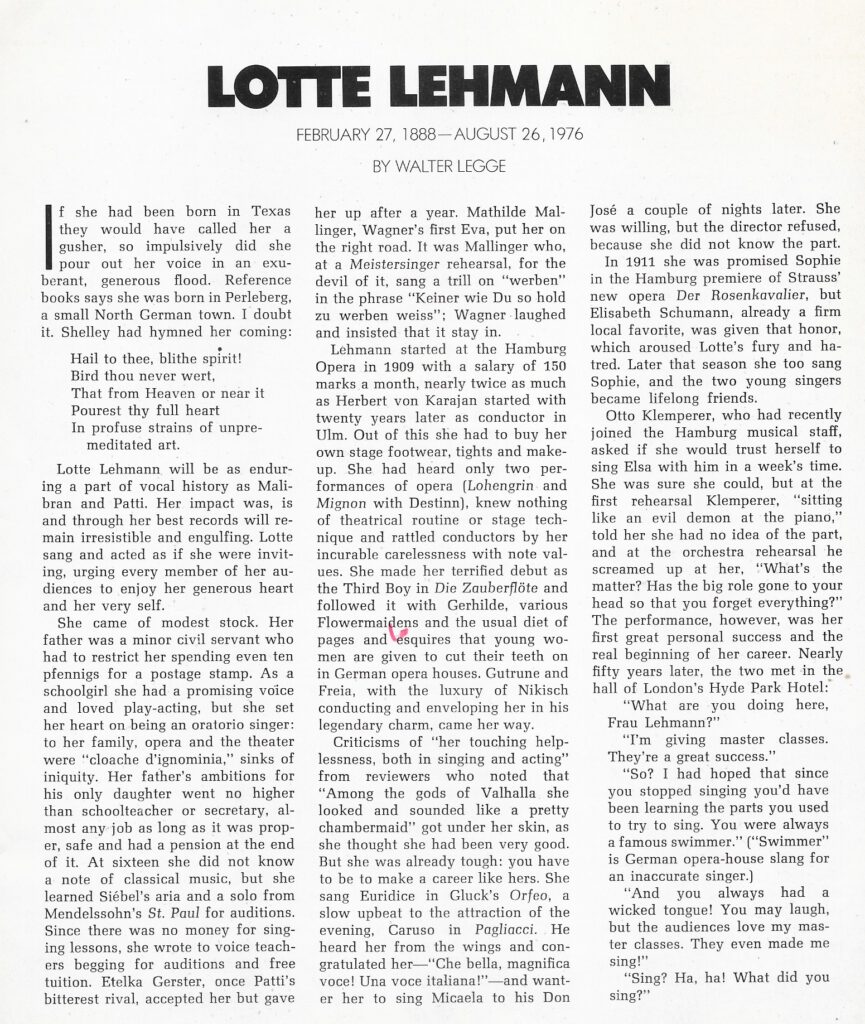

SANTA BARBARA — Contrary to popular myth, she wasn’t the only great Germanic soprano of her time.

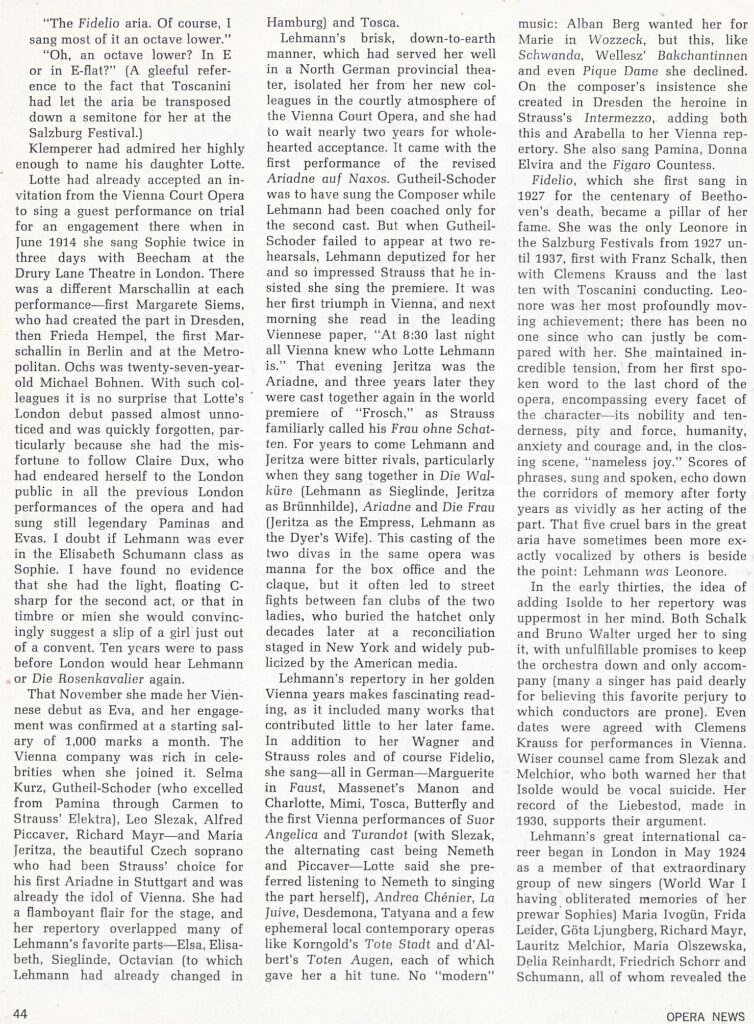

The stately Kirsten Flagstad had a much bigger voice and a better technique. Frida Leider commanded the heroic challenges–Isolde and Brunnhilde–that eluded her. Maria Jeritza was more glamorous, more temperamental. Elisabeth Rethberg mastered the lofty Verdi heroines that she avoided.

Still, Lotte Lehmann was unique.

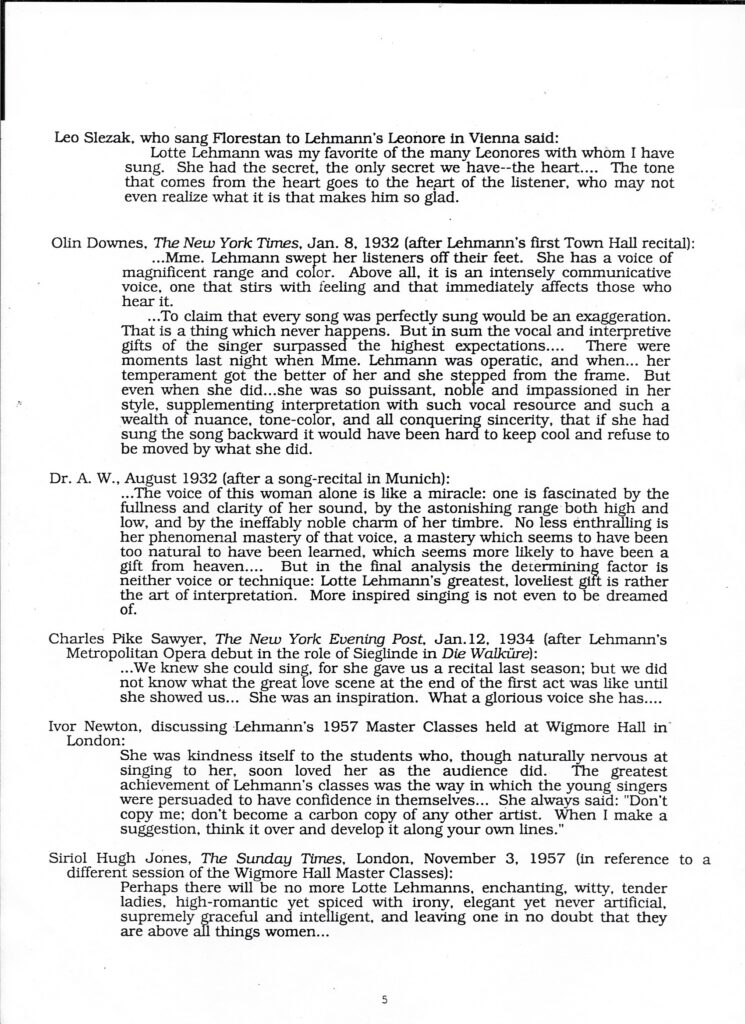

Tenors loved her. “Che bella magnifica voce!” exclaimed Enrico Caruso, who wanted to sing Don Jose to her Micaela. Leo Slezak said “she possessed our secret weapon–the only one we have: heart.” Lauritz Melchior simply called her “ My Sieglinde.”

Conductors loved her. Otto Klemperer, Franz Schalk, Bruno Walter, Richard Strauss and Hans Knappertsbusch sang her praises lustily, and they represented just a small part of a large chorus. Arturo Toscanini found her so appealing, off stage as well as on, that he permitted her the indulgence of a downward transposition in Fidelio’s “Abscheulicher.”

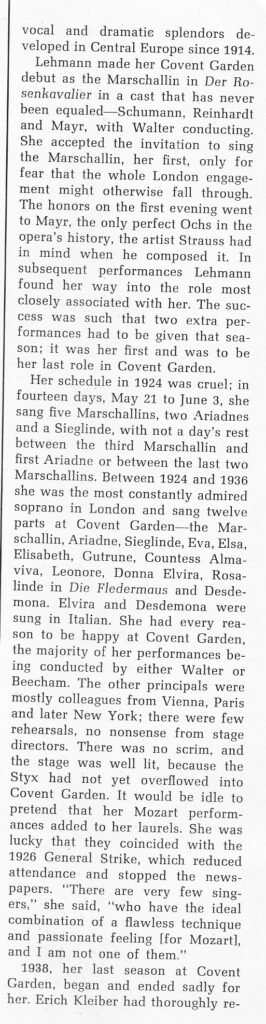

Composers loved her. Citing her “rare fusion of a soulful voice with excellent articulation of the text with genial force of expression and a lovely stage appearance,” Richard Strauss insisted that she sing the premieres of his revised “Ariadne auf Naxos,” his “Frau ohne Schatten” and “Intermezzo.” He was willing, moreover, to temporarily sanction any liberties she would take with the vocal line.

Puccini felt that she was the first soprano who really could validate his “Suor Angelica.” That she did so in the wrong language was irrelevant.

Audiences adored her, from her debut as a bit player in Hamburg in 1910 to her years as a reigning diva in Vienna to her career as a song specialist throughout America to her extended farewells in Southern California.

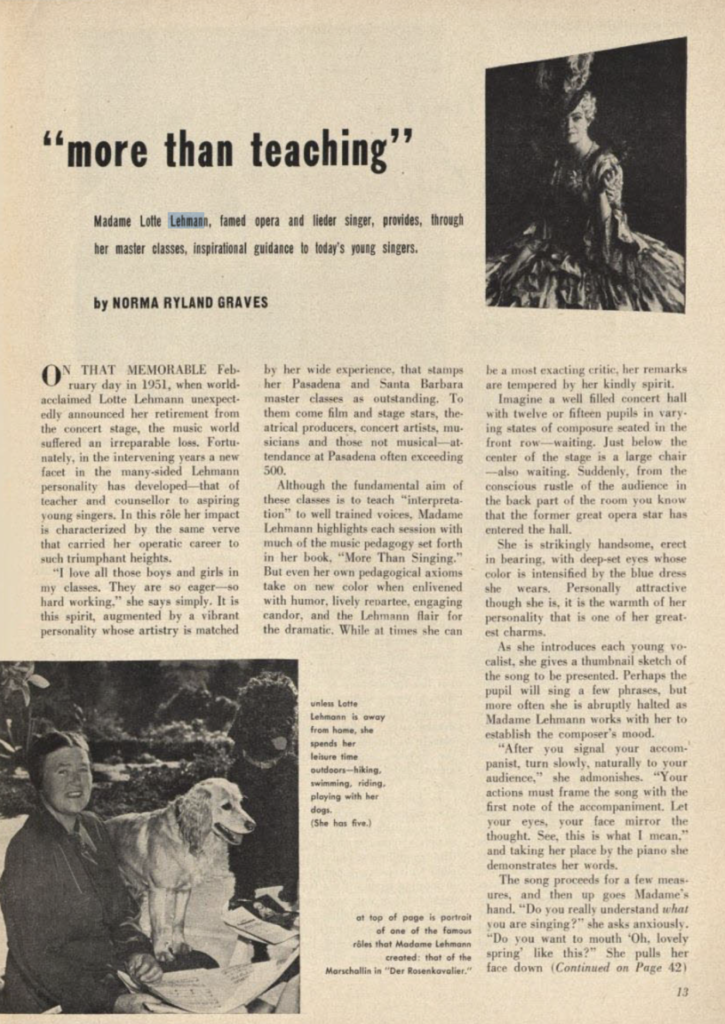

A final performance of her signature role, the Marschallin in “Der Rosenkavalier,” took place with the San Francisco Opera in Los Angeles on Nov. 1, 1946. (The Times review, dated Nov. 2, doesn’t even mention the milestone.) Her valedictory recital followed five years later in Pasadena. The masses continued to adore her in old age as she performed–the verb is emphatically accurate–in public master classes.

Even critics adored her, most of the time. A Beckmesser or two may have lamented her tendency to approximate pitches or distort rhythms as she sacrificed precision to passion. Others worried about her top tones in later years, or her eagerness to usurp lieder that tradition had assigned exclusively to male voices. A few iconoclasts groused that she conveyed housewifely decency even when she wanted to be very complex and very grand.

But no one doubted her profound poetic instincts or took her interpretive rapture for granted. No one questioned the radiance of her tone or the generosity of her spirit.

Lehmann was capable of disarmingly candid self-appraisal. Possibly protesting too much, she liked to admit that her technique was somewhat erratic, especially in matters of breath control. Although she enjoyed a splendid success at the Vienna premiere of Puccini’s “Turandot” in 1926, she said she took greater pleasure in the performance of Maria Nemeth, her alternate in the strenuous title role.

Still, she knew her strengths. “I am a person,” she declared, “who cannot do anything without being totally, compulsively devoted to the effort.”

The effort eventually embraced lecturing, writing, painting and stage directing as well as singing. After Lehmann died at her beloved home in Santa Barbara on Aug. 26, 1976, aficionados everywhere continued to worship her. Fanatics with long and/or rose-colored memories dismissed such soprano whippersnappers as Reining, Bampton, Varnay, Schwarzkopf, Della Casa, Grummer, Steber, Crespin, Soderstrom, Rysanek, Jurinac and Altmeyer. “Very nice,” they invariably clucked, “but you didn’t see Lehmann.”

The world at large, however, proved somewhat fickle. Much of the huge but in many ways frustrating Lehmann discography lapsed into library limbo. A new, more inhibited generation of performers and audiences tended to find her art oddly effusive and dangerously old-fashioned. The ranks of the devout began to thin.

Lehmann would have been 100 on Feb. 27, 1988. It was, clearly, time for revival and reappraisal. It was time for a centennial celebration. UC Santa Barbara, which houses the exhaustive Lehmann archives, provided just that last weekend.

For three busy, potentially hypnotic days, the cold little concert hall–it happens to be called Lotte Lehmann Hall–in this mirage of a campus by the sea was warmed with lectures, concerts, multimedia presentations, panel discussions, fanciful seances and fancy tributes. An “official” biography was introduced. Paintings were exhibited. Rare recordings were played. Hyperbole flowed in sincere abundance.

Lehmann’s erstwhile students came to the shrine. Her friends, colleagues and associates came. Her disciples came. Who says nostalgia isn’t what it used to be?

Ironically, the people who didn’t come turned out to be the ones who could have benefited most from the illustrious examples and poignant testimonials. The crowds, though vastly enthusiastic, were disappointingly small and distinctly mature. Despite the scholarly ambiance, one saw few young faces.

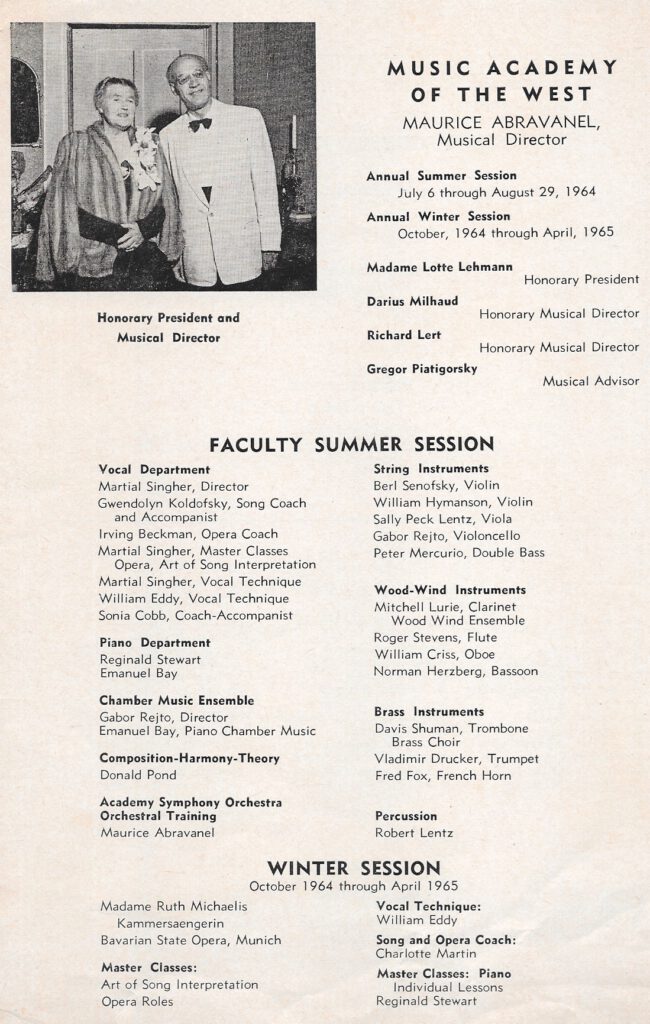

After the inaugural ceremonies on Friday, Maurice Abravanel took the podium. Now 85, he offered vivid recollections of his collaborations with Lehmann, as conductor and as administrator at the Music Academy of the West. He spoke with extraordinary warmth of her impetuosity and her flexibility. He invoked the poetic excitement of her creations and confirmed the prosaic insignificance of her miscalculations.

He was the first of many speakers to stress the singer’s concern for the word and its telling inflection. “With Lehmann,” he said, “expression was everything.”

Variations on this reverential theme were immediately provided, via videotape, by Dolores M. Hsu, UCSB music department chairman; Gwendolyn Koldofsky, Lehmann’s longtime accompanist, and Frances Holden, Lehmann’s muse, companion, rock of Gibraltar and personal Brangane.

Beaumont Glass, erstwhile assistant to Lehmann at the Academy and now head of the opera department at the University of Iowa, offered a thoughtful preview of his new biography of the soprano (Capra Press, Santa Barbara: $18.95).

Paradox clouded the picture that night when Carol Neblett, who for a short time had coached repertory with Lehmann, offered a recital in her mentor’s honor. Contrary to the exalted Lehmann tradition, Neblett sang over-familiar music of Schubert, Brahms, Debussy and Strauss with much luminous tone and little interpretive insight. The words counted for little, and the subtleties behind the words counted for less.

Ironically, Neblett’s duochromatic delivery and chronically glamorous image suggested nothing so much as a latter-day incarnation of Lehmann’s arch-rival, Maria Jeritza.

The symposium reached its high point Sunday morning with a brilliant paper presented by Richard Exner of the Santa Barbara faculty. This imposing literary authority chose a subject–the strange but mutually enriching relationship between Richard Strauss and his librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal–that bore only a tangential relationship to Lehmann. However, Exner explored that subject, and its capricious arguments regarding the relative impact of word and music, with probing wit and contextual wisdom.

Edward Downes completed this most stimulating session with personal recollections of the prima donna in Europe. He mentioned that Lehmann claimed to admire Flagstad’s singing but found her Scandinavian colleague cold. He also mentioned, conversely, that the essentially prim and placid Flagstad admired Lehmann’s singing but found that she enacted Sieglinde “as if doing a striptease.”

To belie the notion that Lehmann always had difficulties with her top voice, the visiting musicologist played an early recording of Butterfly’s entrance aria. Lehmann rode the crest of the climax to an effortless, gleaming high D-flat. It elicited a collective gasp.

Betraying his own special fondness for Lehmann, Downes admitted that the heart-bedecked tie around his neck had been an impulsive mid-interview gift from the prima donna some 50 years ago. It elicited wild applause.

The afternoon session found Beaumont Glass returning to recount Lehmann’s concert career. At the end, he played the famous recording of “An die Musik” as sung by the soprano at her final New York recital. Choked with emotion, she was unable to utter the last grateful apostrophe to her art: “Ich danke dir.” Even now, 37 years after the event, this remains a wrenching document of renunciation.

Redundancy began to set in as Alan Rich, music critic of the Herald Examiner, traced the evolution of Lehmann’s art through successive recordings of the same material. One had to admire his sentimental enthusiasm even if one could disagree with his premise–”She became a more conscious singer with age.”

The concert Sunday night, interesting if not entirely successful, was a ghostly experiment devoted to the monumental “Winterreise.” Some 400 slides allowed us to examine Lehmann’s pretty, naive illustrations–in toto and in nervously changing detail–on a big screen. Meanwhile, Lehmann’s isolated recordings of the songs that comprise Schubert’s tragic cycle were pieced together for a less than cumulative sound track. Under these contrived circumstances, the comic-bookish, essentially amateurish paintings somehow managed to overwhelm the pathos of the music and obscure the ardent professionalism of the singing.

On Monday, Gary Hickling, a bassist of the Honolulu Symphony, offered an illuminating, obsessive glimpse into the Lehmann discography. Then the houselights went down and a shadowy, elderly Lehmann appeared in film clips from her famous master classes. She impersonated a melodramatic Ortrud for an innocent student mezzo. With minimal prodding, she enacted the Marschallin’s entire monologue while croaking the vocal line an octave or two below the normal terrain.

She exuded eloquence and savoir-faire. Music and the theater obviously were in her blood. The sound of applause, she often admitted, was irresistible to her. The documents are important.

Still, one must question their educational value. Lehmann reportedly exhorted her students not to copy her. In her classes, however, she seemed to prefer demonstrating to teaching.

Here, she would say, you smile. Here, you take three steps, raise an arm and look upward. . . .

It looked terrific when she did it. It looked silly when those nice, ultra-American kids imitated her.

The symposium closed with seven of Lehmann’s erstwhile students joining in an awe-inspired if not awe-inspiring panel discussion. Significantly, only one of the participants, the soprano Kay Griffel, had gone on from the Lehmann classroom to a reasonably substantial career.

Actually, many singers attended Lehmann’s classes. But none emerged as an artist who could even approach Lehmann’s stature. If Lehmann knew her own secrets, she did not know how to pass them on.

The evidence suggests that she was not a great teacher. Nor, for that matter, does she seem to have been a great writer or a great painter. It doesn’t matter.

She was a great singing actress. That is enough.

We can see it clearly now.

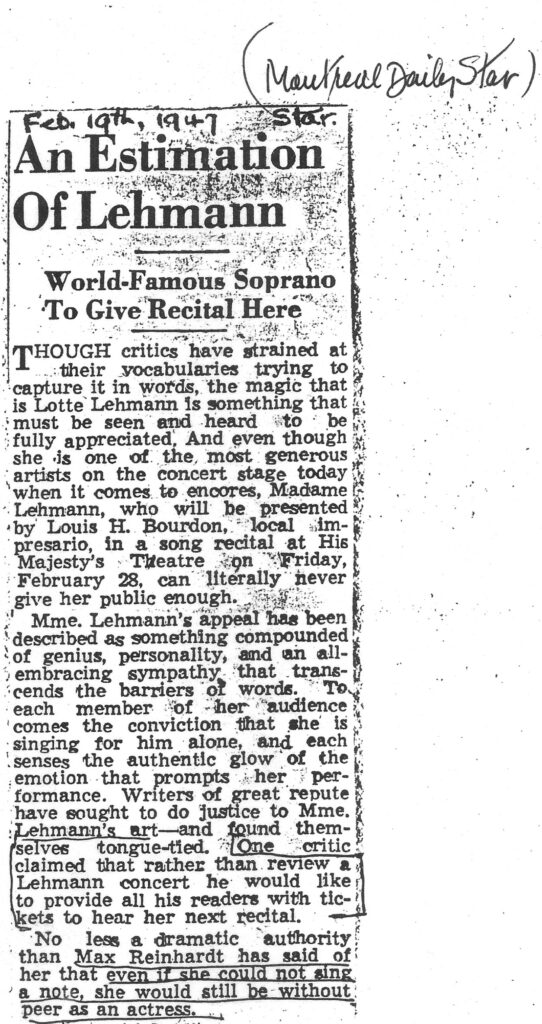

Nelson Eddy

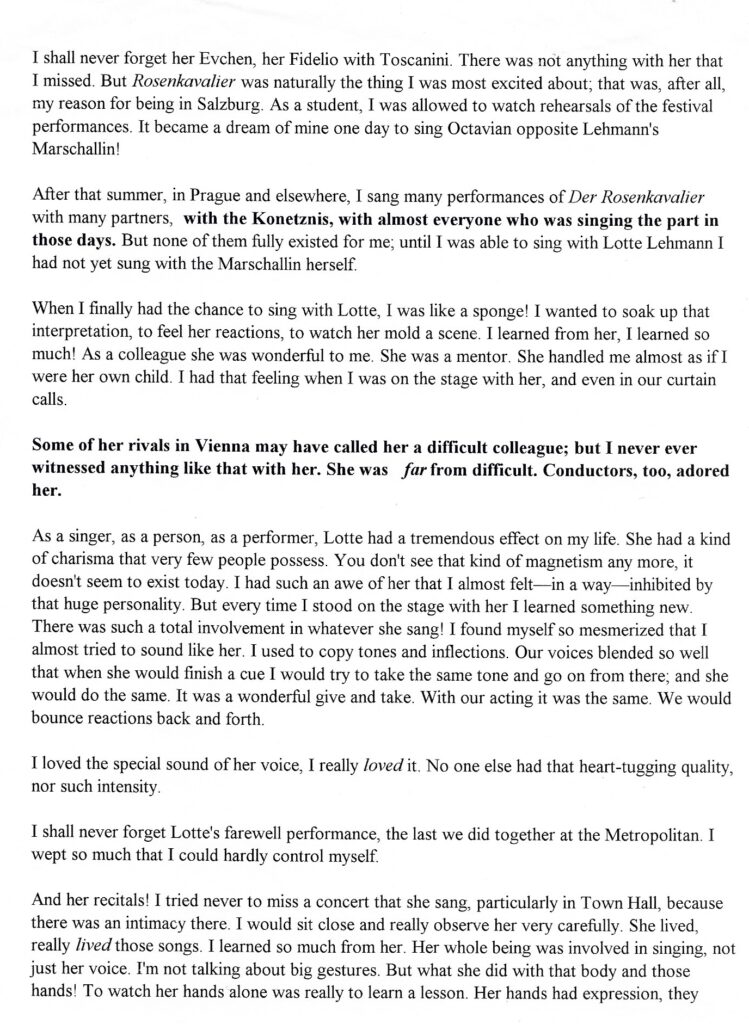

Lehmann was always a movie fan, but the following information can explain her connection to Nelson Eddy, a singing film star. “Eddy was ‘discovered’ by Hollywood when he substituted at the last minute for the noted diva Lotte Lehmann at a sold-out concert in Los Angeles on February 28, 1933. He scored a professional triumph with 18 curtain calls, and several film offers immediately followed. After much agonizing, he decided that being seen on screen might boost audiences for what he considered his ‘real work’, his concerts. (Also, like his machinist father, he was fascinated with gadgets and the mechanics of the new talking pictures.) Eddy’s concert fee rose from $500 to $10,000 per performance.” Later Lehmann coached Jeanette MacDonald who appeared in many of the movies with Eddy. MacDonald actually did sing a few opera performances. After their seventh teaming in Bittersweet did not fare as well in the box office the previous year, MGM decided to split Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald for their next films. Nelson was given his choice of leading lady and he picked Risë Stevens of the Metropolitan Opera. So, in the second photo which shows Lehmann in the same hat etc. as seen with Eddy, you’ll see her with her real opera co-star (she sang Octavian to Lehmann’s Marschallin) on the set for the MGM movie The Chocolate Soldier (1941).