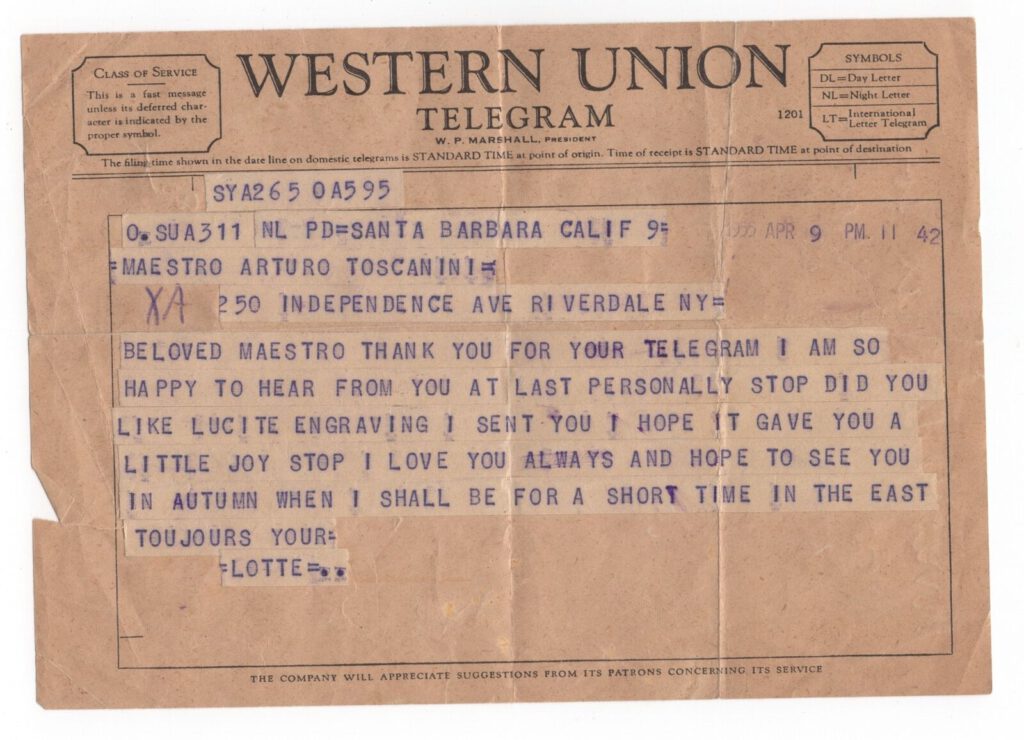

Arturo Toscanini was an important person in Lehmann’s life both as a conductor and as a lover [see below]. Lotte Lehmann & Eleanor Steber discuss Toscanini

Here is what Beaumont Glass wrote of Lehmann’s first appearance with Toscanini: “February 11, 1934, was a major date in Lehmann’s career. On that evening she sang for the first time under the baton of Arturo Toscanini. For him, too, it was a first: the first time that he had participated in a commercial radio broadcast. It was ‘The Cadillac Hour.’ Before Beethoven and after Mendelssohn the announcer touted as tastefully as possible the advantages of the Cadillac car. Lotte sang Dich, teure Halle and Fidelio’s aria. It was a landmark for radio. The response was so favorable that General Motors was moved to sponsor an entire series of classical music broadcasts. The next day Lotte was back in Town Hall, sharing a program with Myra Hess and others for the Beethoven Society. Shortly before their entrance, she whispered to her accompanist: ‘I feel quite calm. The program is easy, the audience here is always nice and appreciative, and there’s no Toscanini to make me terrified.’ Then she walked out onto the stage and there was Toscanini in the front row. Lotte was so startled that she nearly forgot to sing her first phrase. Then, on February 24, she sang her second Metropolitan Opera performance. This time the opera was Tannhäuser. Toscanini was in the audience, with Geraldine Farrar. March 4. Town Hall recital. Schubert, Brahms, Wolf, Strauss. Eight encores. The venerable H. J. Henderson noted in his review that Lotte ‘held the audience in the hollow of her hand.’ That audience included once again both Toscanini and Farrar.”

Here is Lehmann herself recalling an aria first sung with Toscanini: Isolde’s Liebestod: Mild und leise. “Isolde—the role I never sang, the role which I longed to sing through many, many years—never being able to fulfil this dream: my voice was not ‘high-dramatic’—I believe the role would have been the end of my singing career. Oh—at that time of my life I was touchingly foolish enough to say: ‘So be it my end! Could there be a better way of losing one’s voice? ‘ Fortunately I was wisely advised—and buried this dream. But at least I sang the Liebestod! I sang it for the first time under the baton of Arturo Toscanini in Vienna. For me it was one of those unforgettable hours of blissful abandonment, of dying in the surging waves of music, forgetting the world of reality . . . ‘Ertrinken, versinken’ —there is nothing like it.”

Again, we read what Lehmann said of Toscanini: Toscanini Retired? I dare not believe it, says Lotte Lehmann. April 11, 1954 Santa Barbara News Press

We take it for granted that our sun will shine forever. We see it go down in the evening and know tomorrow it will rise again. How would we react if one day we should hear that it would never come back? That it will be with us in a soft afterglow which will envelop the world with subdued splendor—but from now on the warm, glowing radiance will be lost to us. We would be confused and would not dare to believe such news.

Maestro Arturo Toscanini has announced his decision to retire. I dare not believe it.

If anyone has a right to retire it should be he. His whole long life has been complete devotion to music. Perhaps in his eighties he should enjoy the serenity and peacefulness of a private existence. And yet—saying this—I feel the impossibility of imagining him apart from his work, apart from music, apart from creation in music. How will he bear it?

I see his face before me in this moment, his dark brows knitted into a savage black line over his beautiful eyes (which are not as black as they seem, they are actually a soft, warm brown—little golden sparks flicker in their depths). But his glance would be black if he should hear me say that he couldn’t bear to live without music, that I could think his interest in life so limited. …He told me once he has a deep love for paintings, that he could sit before one holding it in his hands, close to his very near-sighted eyes and study it, penetrating its beauty for a long time. He likes to read and is able to do so in many languages. In a rehearsal of Meistersinger in Salzburg, I remember he once corrected the pronunciation of a German singer to the amazement of all of us.

It is hard to know where to start in telling of my reminiscences of the Maestro. I met him first in New York when he conducted his first commercial [radio] broadcast—for General Motors. He had heard me shortly before this in Vienna in the premiere of Richard Strauss’ Arabella. This had been a terrible day for me: my mother whom I had loved more than I can say, had died the day before the performance. It would have been understandable and excusable if I had canceled my appearance. But one could not do that. “The show must go on.” There was no one who could take my place, the house was sold out, it was a tremendous occasion, a Strauss premier. So I sang. Someone told me that Toscanini was in the audience—but I was so deeply unhappy that nothing made an impression on me. On that night I only lived as Arabella…

Later I heard that Toscanini had been very moved when he heard of the circumstances under which I had sung. His comment was: “That is the sign that she is a real artist.”

As a result of this performance he selected me for this broadcast.

I shall never forget the day I went to his hotel in New York for a rehearsal. I had to sing the great aria of Fidelio and Elisabeth’s aria from Tannhäuser.

At this time I was already a well known singer, at home in the great world, having sung in all the important opera houses throughout Europe. So one wouldn’t believe that I could be scared of Toscanini. But where is the singer who is not scared of him! He does not like this at all. It makes him very impatient and he expresses his displeasure in no uncertain terms. He just can’t understand the strange magic of his overpowering personality. I remember how I felt as I looked into those burning eyes, commanding me: sing! I started—the tone stuck in my throat! I almost broke into tears. And stammering that I was just scared to death of him, I tried again. The rehearsal was long and exhausting. Exhausting because of the tremendous inner tension with which I tried to do justice to all his commands.

I really don’t remember how the concert went. I just wasn’t on earth at all. The Maestro was satisfied with my singing—and no crown jewel could have given me more delight than his smile.

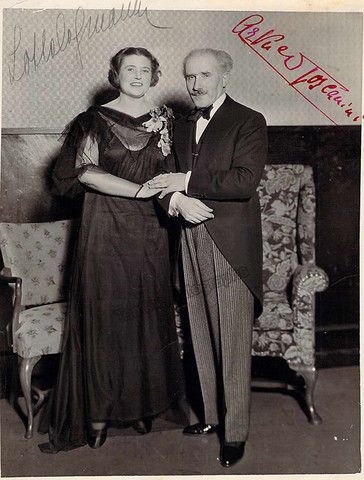

We were photographed together and he was in such a good mood that he permitted with great affability, what I took for granted, not knowing that he hated photographers and anything to do with publicity. I did not realize then that this meeting with him would be a very important day in my life.

Toscanini’s friendship and his enthusiasm for me as an artist have been the climax of my career. Unforgettable were the rehearsals with him in Salzburg where he conducted Fidelio a year after our concert! For us each rehearsal was a performance. There was no possibility of every letting down, of taking it easy. Everyone had to give to his fullest capacity—and even if he had not ordered us to do so, we would have done it, because he himself always gave his whole heart and his whole soul.

Needless to say that in the performance the audience went wild. After the third Leonore overture the whole house seemed to be in a frenzy—and we singers applauded like mad behind stage. Everyone who has seen him knows his helpless gesture of refusal: “It is not I who deserve this praise, it is the composer. I only did what he expected of me.” He has said this so often. Once when in my adoration I perhaps went too far, he said, quite annoyed: “But don’t you see that I am nobody to be glorified as you are doing? I am just a good conductor, that’s all.”

The Vienna Orchestra worshiped him—but they often had to endure fits of his terrible Italian temper which have become legendary. I once heard one orchestra member say to another: “One really doesn’t know how one should feel about this demon of a man. Should one hate him or should one kneel down?”

This remark is very typical. It was the way we all felt about him. But I believe no one ever hated him in reality. All of us wanted to kneel down…

Nerve-racking rehearsals of Die Meistersinger in Salzburg! I shall never forget them. After so many years the memory of them still makes me shudder…

He was never satisfied with anything we did. But instead of going into one of his dreaded fits of fury, he sat there quietly and looked at us with an icy stare of contempt. We were so nervous that we stumbled over the easiest phrase. I fought against tears and finally, unable to stand it any longer, I took my heart in my hand and went to him through breathless silence. I said to him: “Maestro, we want to do what you want us to do. But we don’t know what you want. Please tell us and we will do it.”

He raised his dark eyes and said with the touching expression of a dying dear: “There is no fire in this performance…” No fire! Any fire would have been extinguished by his icy silence…Fire! All right! We threw ourselves into our roles and in the end we got his wonderful smile…

I remember the general rehearsal of Meistersinger as an especially unforgettable experience. Certainly the performance was wonderful but somehow the general rehearsal seemed to me the climax. In the last act when the chorus sings the glorious tribute to Hans Sachs, the singer of the Hans Sachs role was so overwhelmed that he turned around with tears in his eyes and whispered to us: “How can I ever sing now? This demon has completely devastated me with his fire.”

I was in an intoxication of delight and after the performance tore into his room without even knocking at the door. There he stood, scarcely dressed—and I can still see the incredulous look of shock in the eyes of his chauffeur and faithful factotum Emilio as he stood motionless holding the Maestro’s trousers in his hands. But I paid no attention to him. I ran to the Maestro, kissed him, said “Thank you” and was out of the room…

Once in Fidelio I made a dreadful musical mistake in the last act. Knowing that this was a mortal sin, I felt terribly. I could only go to him and beg his forgiveness, but I didn’t dare to enter his room. I stood outside, trembling and wiping away my tears until his very kind wife Signora Carla took me by the hand and pulled me into the room. What could I say? I could only stammer: “Forgive me.”

He turned his sinister glance upon me, but before he could answer I added: “I shall weep the whole night.”

“All right, go home and weep,” was his answer. But I saw a flicker of his smile…

I remember one day as the sunniest of my whole life. In a little village near Salzburg, as was the custom there, a young peasant couple, the poorest in the village, was chosen to have their wedding celebrated in the most spectacular fashion. They received money, all their household furnishings, linen, silver, everything. Our Chancellor Dr. Kurt von Schuschnigg was to be present, the Archbishop was to marry them and everyone with a name and position was invited to attend the ceremony. The Toscanini family was there and I sang in the church. The presence of the Maestro was especially inspiring even if it did make me a little nervous. What a wonderful day! The little village was filled to capacity with all the peasants, appearing in their beautiful fiesta [Lehmann lived in Santa Barbara when she wrote this] outfits. The young bridal couple was surrounded by a glamor they had never before seen or dreamed of seeing.

After the ceremony we participated in the big dinner. I sat beside the Maestro who was in wonderful humor and opposite us sat the Chancellor. We had to autograph one post card after another and that the Maestro did it without complaining was the greatest miracle of this miraculous wedding…After dinner the Toscaninis came home with me and we had such a wonderful time. He could be so simple, so utterly kind, so absolutely different from the demonic figure on the conductor’s podium.

Shortly after this I sang in one of his concerts in Vienna. It was the first time I had sung Isolde’s Liebestod, the ending of that heavenly role which I never sang in opera because it was too dramatic for my lyrical voice. To sing it in concert is rather nerve-racking: one has to sit through the whole long prelude and then the beginning of the aria is difficult because the orchestra doesn’t give any musical cue. One has to start, so to speak, out of nowhere…I told the Maestro that I was terribly nervous and that I would certainly die of shock if out of nervousness I should start with the wrong note. He promised to give me the tone and I mustn’t worry. I really didn’t. But he did. Through half the prelude he hummed the tone and since his voice is notoriously hoarse and rough I could scarcely tell what tone it was…But I started right and everything was saved…I shall remember forever the feeling of intoxication and utter abandon as I sang Isolde’s last words: “Ertrinken, versinken, unbewusst, höchste Lust” (to drown, to merge—unconscious—bliss sublime.) The music was like an overpowering surf in which I sank, lost in the splendor of sound…

And so I feel in remembering my association with Toscanini. The overwhelming strength of his magical personality is akin to the power of the ocean—devastating in its fury—awe-inspiring in its grandeur.

We shall have his recordings—that is true. In his perfection he will be with us. But that we shall never again be able to feel his nearness, to see him conducting, to see his face tortured through concentration, that I cannot and dare not believe.

He may have a long rest after exhausting work, he may feel well again and return to us.

I sent him a telegram on his birthday saying: “Years do not count with you. You are ageless. Stay with us for many years to come and make this world a better one.”

I say it again with all my heart.

Some Lehmann/Toscanini Connections

Beaumont Glass writes: “Her fear of a conductor’s wrath led her to turn down a very special offer. La Scala had invited her to sing Eva in Die Meistersinger, in Italian, at the special request of Arturo Toscanini, who would be conducting. She had heard harrowing tales of his fanatical obsession with precision. Since her conscience was never totally spotless where musical accuracy was concerned, she was afraid of becoming a target for his tempestuous temper. Later she regretted immensely the missed opportunity. It was many years before she had another chance to sing with him; and, when she finally did, their collaboration became one of the incomparable artistic highlights of her life.”

Here’s another missed opportunity with Toscanini revealed by Beaumont Glass: “Winifred Wagner, the widow of Richard Wagner’s son Siegfried and reigning queen of Bayreuth, heard Lotte’s Eva and had a talk with her later. In an interview for a Munich paper, Lotte recalls the gist of their conversation:

She told me it was the personal wish of Toscanini that I should sing Eva and Sieglinde next year in Bayreuth. I don’t yet know if I shall; probably I would not be able to participate in the Salzburg Festival if I did.

Here Glass quotes Lehmann: Lotte took the time to confide her happy feelings to Viola Westervelt, who had returned to France, in a letter dated March 9, 1934:

Up to now everything has been a true triumph for me—I can say that without exaggeration. Never before has a tour been so untroubled, so full of unforgettable impressions, as this year. Everything has gone so well and so beautifully that I often think my good mother must be with me….The Elisabeth was a stunning success—[Lawrence] Gilman wrote that I would have been the fulfillment of Wagner’s dreams if, eighty years ago, he could have had the luck to hear me. On the 4th I had a sold-out Town Hall recital; the people simply went mad and I sang exceptionally well—you know how seldom I ever feel that—but I was as if intoxicated and raised above everything terrestrial by that enthusiasm. The charming Farrar and Toscanini were at the recital from the beginning to the end. Toscanini means to me a very special chapter in my life. This man, before whom everyone that sings or plays for him trembles, is so wonderful to me, that I am quite speechless. After the recital he said to me that absolutely no one compares to me (“une artiste sans égale“) and that no superlative would be too high to tell me how delighted he is. I am so proud—I almost wept for happiness. ….The Herald Tribune (a third-ranked critic, so I hear [Jerome D. Bohm]) tore me to pieces. I would have been very upset by that if Toscanini had not said such beautiful things to me. He inscribed his picture to me: “alla cara Lotte con affetto, amicizia e grande ammirazione” [to dear Lotte with affection, friendship, and great admiration]….”

More from Glass: “During this time, the affair with Toscanini, which was to re-ignite again in the blaze of their collaboration at Salzburg that next summer, was causing Lotte considerable distress, as she confessed to Mia Hecht:

[March 4, Indianapolis] T. was with me once in New York. The flame is extinguished, I cannot deceive myself any more. He is different. And even if he is overcome by the moment—it is nevertheless the passion of the moment, not of the heart… I can see it very clearly and gradually come to terms with that. But something incomparably precious has been broken for me… He has taken the whole affair as an impetuous adventure, above all he has represented it as such to me, and is surprised—and not even pleasantly surprised—that I can’t get over him. He kept saying: ‘Mais tu es une folle! Pourquoi m’aimes-tu encore? J’avais oublié toutes les femmes—pourquoi m’as-tu éveillé? Soi bonne—oublies-moi…‘ [‘But you are crazy! Why do you still love me? I’ve forgotten all the women—why have you aroused me? Be good—forget me.’] He was sweet and enchanting—but a world away from me…. I can also not understand that he never mentions my singing in his concerts any more… And yet he certainly loves me more as an artist than as a woman. Oh, much more!! He came to my recital and was very enthusiastic and very moved….”

Glass writes more on Toscanini in Lehmann’s life, both on the professional and the personal level: “Bruno Walter had wanted Lotte for the title role in Gluck’s Iphigenie in Aulis at Salzburg. It had already been announced. But Lotte wanted to save all her concentration and strength for Fidelio, her first opera with Toscanini. She begged off. Walter reluctantly canceled the production. Toscanini’s letters, a year later, are just as ardent as they were when he and Lotte started their affair: I have gone to Piazze… My shoulder and my arm need rest and care….Don’t forget me, Lotte darling. And think and know always that you are the only woman who is in my heart—the only woman that I love—the only woman who can make me relive the sweetest, most voluptuous moments….who knows how to make me young again!!!… I want you for me alone—do you understand?…

Evidently Lotte had reproached him for not writing more often. He attempted to convince her that her place in his heart was secure. But it seems that he, too, craved some reassurance.

I am desolate. Another very short and very sad letter from London. Why, darling, can’t you understand that I can love you—not forget you for a single moment—and still be stingy with my writing? You are a graphomaniac. You have the talent for writing—I, no!!! But my heart is good, sensitive, sincere, and in love with you [underlined twice!]… Yes!! In your letters you give me a joy I can’t even express in words….Is it true, what you say? Is it true, Lotte? ‘My mouth belongs to you alone, I kiss no one as I kiss you.’ You do not say all that just to make me proud—happy—to make me smile with joy…You will be in Milan the evening of the 24th. And I on the train the whole night. It will be impossible to see you… But possible to suffer! Lotte darling, be reasonable — don’t write me any more letters like the last ones. Kisses—caresses—everywhere

Your Maestro

Lotte still felt insecure. Again he [Toscanini] tried to reassure her: Next Wednesday I shall be in Salzburg….I arrive alone!!! I am going for two days to the Hotel Europe. Where will I be able to see you?? Will you send me two words at the hotel? Not for the moment do I love you—always I love you—even when I do not write to you….My arm is not doing well—the “cure” did nothing. Poor maestro!! You will see, when I start to work. I am never cold with you—one cannot be!!! No one can resist your voice when you sing—your mouth when you give your kisses—your body when you surrender to voluptuous feelings!!!…I am sorry for [Bruno] Walter that you gave up Iphigenia… but for you I believe that is the best… You have worked too much… And poor Mayr? What a tragedy!”

Glass writes: “Lotte’s beloved colleague and friend, Richard Mayr, was dying. His last, lingering illness cast a shadow over an otherwise brilliant season at Salzburg….One of Lotte’s summer projects seems to have fallen through: she had planned to make a movie. It was to be the story of an opera star who tries in vain to give up her career for the sake of home and family. It would be filmed in Austria. The English version of the title was Farewell to Fame. What happened? Perhaps Toscanini insisted upon earlier rehearsals at Salzburg….At Salzburg the sensation once again was Toscanini. This summer, for the first time, he conducted opera there. For him, ‘conducting’ meant staging as well. He acted out all the rôles, showed the singers their gestures and facial expressions. Everything came out of the music, as it must in an ideal performance. The stage directors seem not to have resented this invasion of their territory, since the results were so spectacularly successful that everyone involved in the productions could bask in reflected glory. First came Falstaff, hailed as a revelation by the musical world. The whole production was considered to be about as near to perfection as mortals can aspire. Then Fidelio. Toscanini and Lehmann set Salzburg on fire. Lotte’s Fidelio had already come to seem as much a part of Salzburg as the cathedral or the castle. She had sung the role there every summer but one since 1927, under Schalk, Krauss, and Strauss. But with Toscanini everything seemed to be reborn. Here, from My Many Lives, is Lotte’s recollection: Toscanini? He made Fidelio flame through his own fire. There was thunder and lightning in his conducting—his glowing temperament, like a flow of lava, tore everything with it in its surging flood. I shall never forget the wave of intoxicated enthusiasm which broke from the Salzburg audience after the third Leonore Overture [played between the dungeon scene and the finale]. There was something almost frightening in the storm—but the maestro let it break over him with his characteristic look of helplessness. It was as if he were saying: ‘You should honor not me but Beethoven.'”

Much later in Lehmann’s life, Glass writes: “After the third Town Hall recital, Lotte went to visit Toscanini. [and wrote:] Dearest Frances — that man is a miracle. I have no other word. How is it humanly possible that a man of eighty–three had more sex appeal than anybody I know? First, when I came in, he looked rather frail, a little stooped, and somehow so touchingly old in his red house jacket. Signora Carla [his wife] was always there, tripping on unsure feet like a ghost, talking (almost incomprehensibly) and listening and watching and always smiling very benevolently. Two good old people, you would say. Grown old together, belonging to each other, understanding each other. Moving. Touching. But then his eyes, looking at my face, slowly lost the kind and almost absent-minded expression, grew darker, and full of fire—and suddenly the touching old man is a rather dangerous-looking person who makes you feel: this is like old times, this is like Salzburg and Paris and Vienna…. Quite the same old devil, whispering to me: ‘For heaven’s sake, if only we could be alone….’ Can you imagine??? Eighty-three!!!! I can’t get over this!!! On the whole: he is an adorable man and he really and honestly loves me…. He said to me softly again and again: ‘I love you and I shall love you always, always, as long as I live.’ I feel rather silly….Maestro said to me just now on the telephone that I am very beautiful…. What a pity that he cannot see quite clearly—or better: what a blessing!!!”

At the very end of Toscanini’s life Glass writes: “The next stop was New York. Lotte had lunch with Toscanini on October 16. The next day she wrote to Frances: Maestro has aged very much. He is really very frail, almost blind. He was pathetically happy to see me and was very flattering: ‘More beautiful than ever and very slender….’ So he saw that!!! I am so glad that I saw him. He moved me very much.”

From the Lehmann bio by Beaumont Glass, here is the story of the Toscanini love letters that Lehmann tore up and tossed into the fireplace after Maestro’s death. But they weren’t burned. Here’s the relevant portions: “The fragments were rescued from their bed of cinders and stuffed into a secret compartment behind a file cabinet drawer in the den. There they remained, unread and forgotten, until very recently, when odd bits of them happened to fall into the files. Soon many pieces were found that fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. But there were frustrating gaps at some of the most interesting points. My long, thin arm and flexible fingers finally managed to dig out the last remnants from the depths of their very inaccessible hiding place. At least the most crucial lacunae could finally be filled. There are passionate love letters, postcards, inscribed photos, and an astonishingly indiscreet telegram to a London hotel where Lehmann happened to be staying. All were fascinating to decipher. Almost nothing was dated; but it was generally possible, from internal evidence and knowledge of Lotte’s whereabouts, to reconstruct an approximate date for each item. Frances Holden, Lotte’s only heir, decided that the reassembled Toscanini letters should be sealed for a certain number of years.

Much of the content illuminates the close emotional bond between two supremely great artists whose inner lives would seem to be of legitimate interest to the world. What obviously began as a tremendous passion for both of them, ripened—eventually—into a deep and lasting love. It was one of the very few deeply-rooted relationships in Lehmann’s life, the others being those with her mother, father, and brother; with her husband, whose love continued to be precious to her, if in another way; and with Frances Holden, the companion of her later years.

Since Lotte did not speak Italian and was not yet fluent in English, Toscanini wrote to her in French. In the following letter he starts to address her with the formal ‘vous,’ but soon—at the words ‘I love you’—shifts to the intimate ‘tu.’

My dear — my divine Lotte — I feel as if I’m going mad… I am very, very tired — and every day I have rehearsals that crush me and give me no single day of real rest….I cannot speak to you on the telephone since there is always someone listening. I’m going mad, believe me, my adorable Lotte….and I would like to have you in my arms at this very moment….It seems that since this passion which almost drives us mad is not legitimate, we are having to expiate that sin that is so dear to us before committing it!…

Tomorrow I have a rehearsal (11:30 until 2 in the afternoon). Wednesday morning — rehearsal. In the evening — concert at Hartford. Thursday — rehearsal in the morning — concert in the evening. That is my life — dear Lotte — I am dying of desire to see you. To speak to you — I have so many things to say to you — I have almost never spoken with you — it seems as if I do not know you yet and yet I love you like a madman… Yes, yes, I love you, Lotte — I love you. You are like a dream in my spirit. And what a beautiful dream!! Do not stop writing me those beautiful letters full of love and of enthusiasm. Pursue me — when you will be far from me — with your letters and save me from the emptiness of my heart. Good night, dear Lotte — my love — I kiss you on your eyes and on your lovely mouth — Oh, how beautiful you are! I love your portraits — but I would like to have smaller copies of them — to carry around with me always — in my pocket. Do you understand?

Mille baci lunghi — infinit — deliranti [a thousand long kisses, infinite, delirious]

Mae….

(The surviving fragments, like the photos, are signed ‘Maestro,’ which is what nearly everyone called him in those days.)

How Lotte felt can be gleaned from several letters to her confidante, Mia Hecht:

[March 6, 1934, from Toledo, Ohio (on tour)] I had a wonderful letter….He wrote that he was suffering ‘comme un chien‘ [like a dog] and ‘je vous aime, oui, oui, je vous aime…’ [I love you, yes, yes, I love you] well, I am totally out of my mind….[later that month, from Reading, Pennsylvania] Mia, I am half crazy. These ever more intense letters are killing me. I gave him two postcard-sized pictures of me…and he wrote me, quite madly, that he keeps them next to his heart at night and kisses them like a madman and is dying of desire for me, etc., and laments that there is no chance to be alone together! He seems—or so it looks to him—to be constantly watched. He wrote ‘quelle vie de chien…’ [what a dog’s life.] It is good that we are sailing soon; my nerves are destroying me totally. It also seems that people are talking already. We were recently at [Olin] Downes’ party [then the leading music critic of The New York Times]…and he said: ‘What is this about you and Toscanini? I think your husband must take care of you…’ It was a joke—but it’s strange nevertheless, isn’t it?

[March 21, New York] The thing between T. and me has taken on unforeseen and unwanted dimensions… It is good that I am leaving—I can’t take any more, I am at the end of my strength, my nerves are finished… Otto is sad, he feels everything—he said yesterday that I no longer seem to be living at his side, but rather in some other world, since I met T…. I could not even deny it… Now I don’t know what will happen….

Lotte had to leave New York all too soon, first for a recital in Boston; then, March 22 on the Berengaria, to return to Europe. On that day Toscanini wrote her an ardent, rather touching letter. Adoratas and divinas are underlined two and three times. He and Lotte shared a common partiality to multiple exclamation marks.

Mia cara — adorata — divina Lotte [‘my dear, adored, divine Lotte’; ‘adorata‘ is underlined twice, divina‘ three times!], I am like a madman!!! I cannot believe that you have left… The reality is killing me… Lotte, what a miserable, unhappy life mine will be now that I have no longer the hope of meeting you somewhere — of hearing now and then your divine voice which so sweetly soothes my soul, my ears, and all my being!!! Oh, how far away you are from me by now!! It makes me weep… [A mutual friend] told me that you telephoned at 9 o’clock and that a woman’s voice had answered… Certainly someone gave you the number of my wife’s room, not my number; for I was waiting for you with fever in my soul. I didn’t fall asleep until 7 in the morning — I read almost all of your letters while waiting for your sweet call — then, I believe, I was overcome with sleep — but I dreamed and in my dream I heard your voice — I answered, saying… Lotte darling, I love you — sending you a kiss through the telephone, which was near me under the bedclothes, and I embraced it as if it were my dear Lotte… When I woke up, the dream and reality were confused in my head. [The rest of the letter, if there was another page or more, is missing.]”

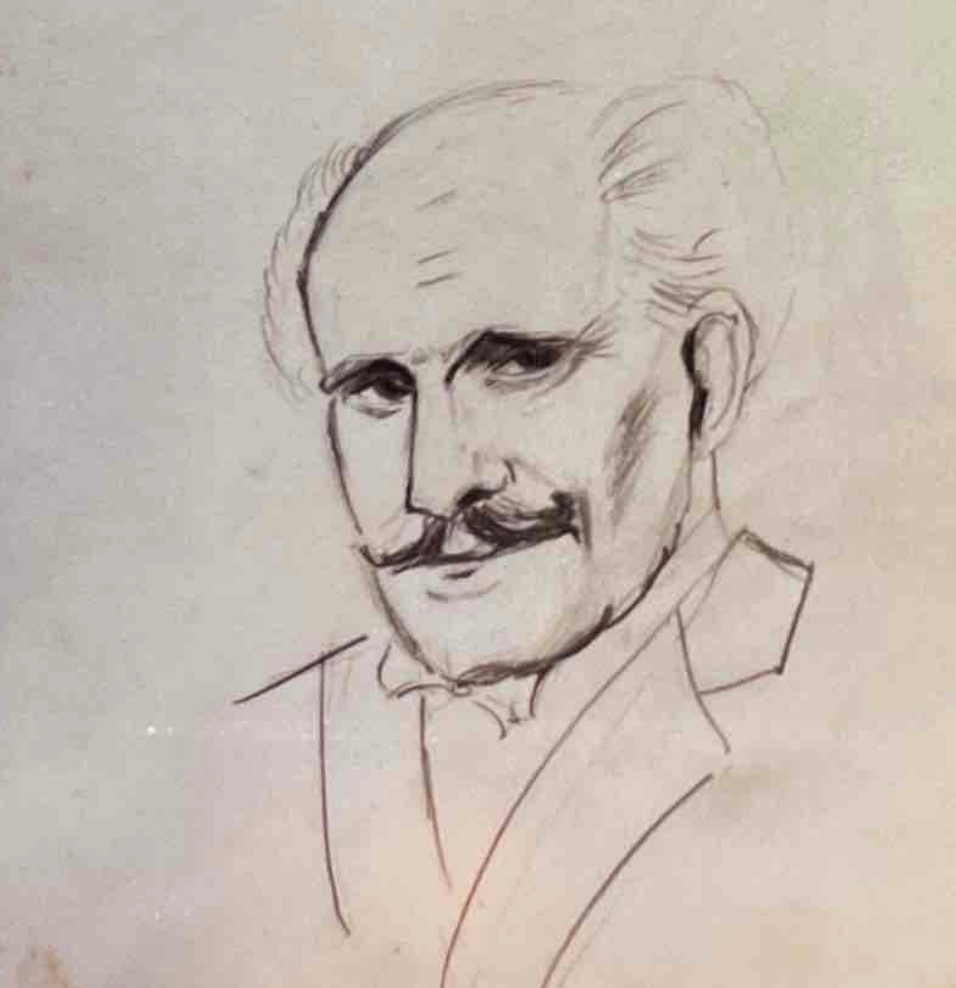

Here’s a portion of a piece that Lehmann wrote about Toscanini for a 1937 edition of Vogue magazine.