Gwendolyn Koldofsky was Lehmann’s final pianist. First a brief bio and then much more information about this remarkable woman. And you can listen to an interview with one of her very successful students, Paula Fan. Here’s a link to a whole page on Mme Koldofsky.

Gwendolyn Koldofsky was Lehmann’s final pianist. First a brief bio and then much more information about this remarkable woman. And you can listen to an interview with one of her very successful students, Paula Fan. Here’s a link to a whole page on Mme Koldofsky.

Gwendolyn Koldofsky (née Williams) was an accompanist, voice coach, etc., born in Bowmanville, Ontario, 1 Nov 1906. She studied piano in Toronto with Viggo Kihl, in London with Tobias Matthay and accompanying with Harold Craxton, and in Paris with Marguerite Hasselmans. She married the violinist Adolph Koldofsky in 1943 and lived in Toronto until 1944. After spending a year in Vancouver she settled in 1945 in Los Angeles, where she was engaged to teach accompanying – a position created for her – at the School of Music of the University of Southern California, which she held until her retirement in 1990. Koldofsky gave master classes for singers and accompanists at other universities and music schools in North America. She accompanied (in North America, Europe, and the Far East) Rose Bampton, Jeanne Dusseau, Herta Glaz, Jan Peerce, Hermann Prey, Martial Singher, and her own pupil Marilyn Horne. She assisted Lotte Lehmann on many tours during the latter’s last 8 years of performing and for 11 years was Lehmann’s accompanist and coach-assistant at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara. A recording of the Santa Barbara farewell recital given in 1951 by Lehmann and Koldofsky is available on CD. Here’s a sample: Seligkeit

In 1961 she accompanied singer Salli Terri on an album of folk songs. She moved to Santa Barbara in 1991 and continued to teach at the Music Academy of the West.

In a recent interview Gwendolyn Williams Koldofsky, one of Lehmann’s last accompanists, spoke of her memories of Lehmann. “She possessed a rare, heavenly quality of voice and was a great actress. In her teaching and her singing she could do the same lieder over and over again, bringing fresh thoughts and a new vocabulary to the work. The artistic convictions and charisma we hear about so much—it was a beautiful experience! I have been with great singers all my life, but there was something about the unique quality, the sound of her voice, and her interpretations that were wonderful…”

Mme. Koldofsky joined Lehmann for her West Coast tours after 1943. She continued teaching the art of accompaniment both at the Music Academy of the West and at the University of Southern California, until her retirement. One of her famous students, Martin Katz, taught at the Music Academy of the West.

So much for the official bio. You’ll find an obit below.

I heard the final recorded “farewell recital” and understood that Koldofsky brought the same sensitivity to Lehmann’s needs that Ulanowsky possessed. Able to adjust the rhythm to allow the extra breath, the nuances of phrasing, knowledgeable in the repertoire and seemingly unflappable, Koldofsky was a perfect choice.

While at the Music Academy of the West I met Mme. Koldofsky and observed her patient work with fellow students. I’m grateful to have known this elegant, dignified and respected person.

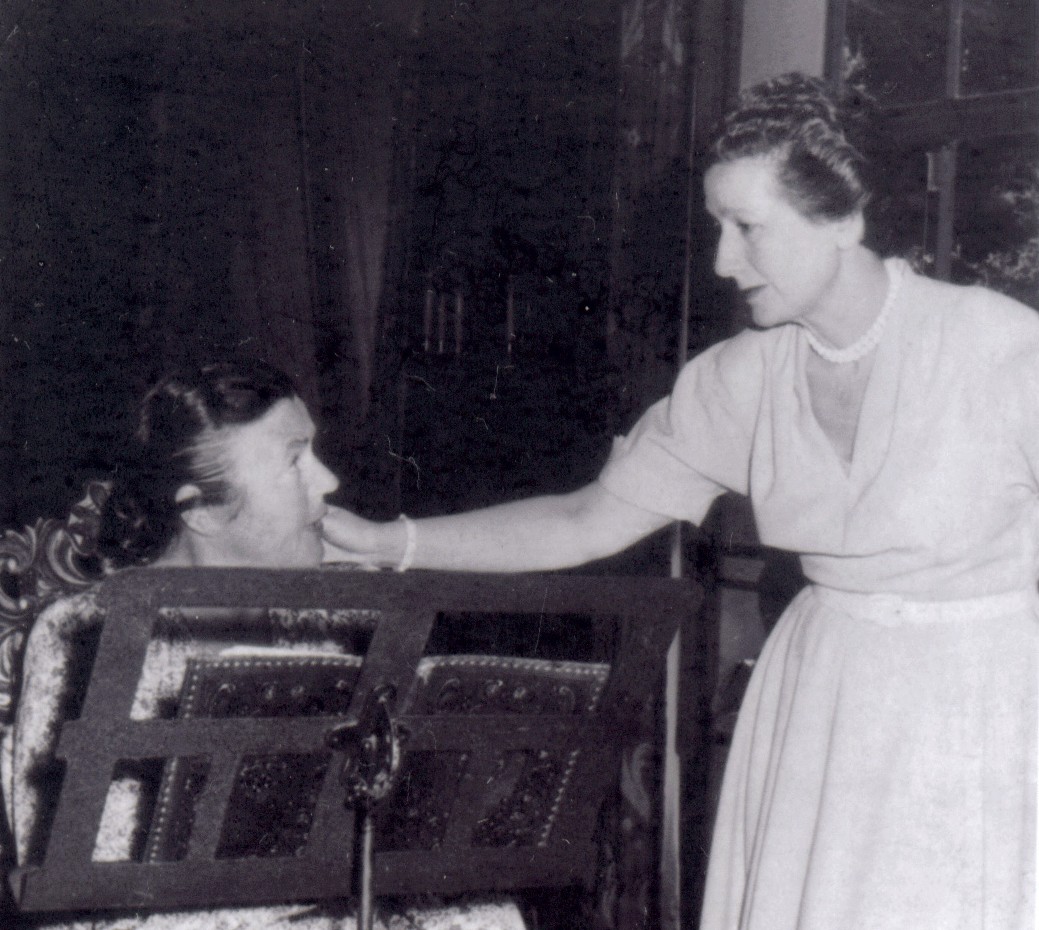

Gwendolyn Koldofsky Playing in Lotte Lehmann Master Class

Chris Foley writes the following: In the short time that I studied with Gwendolyn Koldofsky at the Music Academy of the West, she often spoke fondly of her longtime collaboration with Lotte Lehmann. I was very glad to have recently found a six-and-a-half minute YouTube clip of a 1961 Lotte Lehmann master class, in which she coaches Jeannine Wagner singing Brahms’ “Sonntag” with none other than Koldofsky herself at the piano. This master class dates from the time after Lehmann had stopped singing professionally, however, she still sings one of the more convincing performances of “Sonntag” you’ll ever hear, an octave lower than written. For all those who knew Lehmann and Koldofsky, here’s a rare moment to see them in their prime over 45 years ago…

with Koldofsy

Koldofsky herself wrote: Some Ideas on How to Learn a Song or Aria

1. Read the poetry or a translation of the poetry. Songs are not abstract pieces, they are poems that have been set to music by a composer. Before even looking at the music, look at the poetry; in the case of a song in a foreign language, look at the translation of the poetry. Better yet, translate it yourself in order to sharpen your language skills. This first step is vitally important because it allows you to interact with the poem on its own terms, allowing you to discover important aspects such as line, syntax, vocabulary, trope, rhetoric, metre, and rhyme that may be transparent in the poem’s musical setting.

2. Carefully learn the pronunciation of the poem in the original language. Pay careful attention to all the details of pronunciation that you have so meticulously learned in diction class.

3. In the original language, read the poem aloud. Pay attention not just to the sounds of the language, but to syntax and intonation, trying to sound as idiomatic as possible. Inject meaning into your recitation–don’t just recite syllables out loud. Think of how a native speaker of the language would recite the poem. Many famous composers of art song are known to have recited a poem at length as a way into setting it to music.

4. In the original language, read the poem aloud in the rhythm of the vocal line. This will give you clues as to how the composer heard the poetry and how he/she may have wanted to interpret the text musically, ie. what lines of text are repeated, what words are emphasized, how fast or slow is the declamation of text, how important are the poem’s line breaks and where they occur in relation to the breath.

5. At the piano, play the vocal line in the right hand and the bass line of the piano part in the left hand. This may take awhile, but is worth the effort. Now that you know something about the composer’s setting of the text, this process will give you further musical clues regarding the song’s melody, contour, tessitura, harmonic direction, and phrase structure, as well as help you to understand and hear the structure of and relationship between the vocal and piano parts.

6. Now learn the music. You’ll be surprised.

Gwendolyn Koldofsky, Accompanist, Dies at 92

PIANIST AND VOCAL ACCOMPANIST Gwendolyn Koldofsky, who raised the stature of accompanying to a recognized art, died Thursday, Nov. 12, at her home in Santa Barbara. She was 92. Koldofsky, distinguished professor emerita at the USC School of Music, founded the school’s department of keyboard collaborative arts and both designed and established the world’s first degree-granting program in accompanying, first offered in 1947.

“Professor Koldofsky was a pioneer in the field of accompanying, and the status that field has attained is directly attributable to her efforts,” said Nancy Bricard, professor emerita of keyboard collaborative arts at the School of Music. “She devoted more than 40 years of academic and musical excellence to this university. I know of no professor who has ever served in a more dedicated fashion. She has been, and will always be, an inspiration to students and faculty throughout the field of music.”

Koldofsky taught accompanying, song literature and chamber music at USC from 1947 to 1988. She was also a longtime member of the faculty of the Santa Barbara Music Academy of the West, where she served as director of vocal accompanying from 1951 to 1989. She judged competitions, lectured and taught master classes for accompanists, singers and ensembles throughout the United States and Canada. Among her many students were mezzo-soprano Marilyn Horne, pianist Martin Katz and soprano Carol Neblett.

“Few vocal coaches working today could match Gwendolyn Koldofsky,” said Larry J. Livingston, dean of the School of Music. “Her acquaintance with the accompanying repertoire – especially with piano-vocal music and the art song – was without equal. Our program in accompanying continues to be one of the finest programs in the world, due largely to her vision, influence and leadership. Her death is a painful loss to our school and to the world of music.”

Seattle voice teacher Roberta Manion, who worked with “Madame K” during summer sessions, called her very tough but very fair: “She is extremely meticulous in every detail,” Manion told the music critic of the Seattle Times in a May 1984 interview. “Nothing gets past her. Her comments are always very correct and polite; she also can pull off the velvet gloves and those eyes can flash. But I have never seen her be unkind. She is really beloved.”

For more than 40 years, Koldofsky appeared as an accompanist throughout the world, working with such distinguished artists as Rose Bampton, Suzanne Danco, Herta Glaz, Mack Harrell, Marilyn Horne (her former student), Jan Peerce, Hermann Prey, Peter Schreier, Martial Singher and Eleanor Steber. She accompanied the legendary soprano Lotte Lehmann for eight years, as well as her own husband, the British-Russian violinist Adolph Koldofsky, a student of Ysaye and Sevcik.

“I have seldom had violent disagreements with those I accompany,” Koldofsky told the music critic of the Seattle Times in 1984. “That’s because we both focus on the real nature and depth of the music. Certainly there are always differences of opinion about how fast or how loud a phrase ought to be. But part of the art of accompanying lies in finding how many beautiful, logical interpretations of the music there can be.”

A very nice obit. Now a bit more biography:

Gwendolyn Williams Koldofsky was born Nov. 1, 1906, in Bowmanville, a small Ontario community near Toronto. She was from a musical family and grew up with a tremendous amount of live music in her home.

She received her early training at the Royal Conservatory in Toronto as a student of Viggo Kihl, the noted Danish piano teacher. When she was 17, she went to England to live for several years with an aunt, a concert singer, and there continued her studies in piano with Tobias Matthay. She pursued special studies in ensemble playing and accompanying with Harold Craxton, the eminent English accompanist and teacher. Later, she spent several months in Paris studying French repertoire with Marguerite Hesselmans, a disciple of Gabriel Fauré.

When she was 20, Koldofsky returned to Canada and “had the great good luck of being plunged into an accompanying career almost immediately when Jeanne Desseau, our greatest Canadian soprano, asked me to play for her,” Koldofsky related in a June 1993 interview with the Eugene (Ore.) Register-Guard.

One musical engagement led to another at an exhilarating pace. A year after her return to Canada, she met and soon married Adolph Koldofsky. For the next quarter century, she accompanied all of her husband’s solo recitals and played every form of chamber music with him on concert stages around the world.

Koldofsky received five of the highest honors given at the USC School of Music for excellence in performance and teaching, and received a certificate of honor from the International Congress of Women in Music.

After her husband died in 1951, she founded in his memory an annual scholarship, the Koldofsky Fellowship in Accompanying, at the USC music school.

Koldofsky is survived by her nephew, Dane Williams. There will be no funeral. Contributions can be made to the Gwendolyn and Adolph Koldofsky Memorial Scholarship Fund at USC or to the Music Academy of the West.

Here’s what Beamont Glass writes of Koldofsky in his Lehmann bio:

There was a new accompanist for Lotte’s West Coast recitals after 1943: Gwendolyn Williams, now also very well known as Gwendolyn Koldofsky, her married name. Paul Ulanowsky was so much in demand in the East, that it was more and more difficult for him to free himself for transcontinental tours, especially in wartime, when travel was unpredictable and complicated.

Once, for instance, Lotte’s plane from Toronto could not land in New York and had to return to Toronto. There seemed to be no way to get to New York for her concert. Frances, who was with her, managed to get space for them both on a troop train. They arrived just in time.

For the rest of her singing career, Lotte continued to engage Mrs. Koldofsky as her accompanist for recitals in the western states. Superb musicianship and an impeccable sense of musical style were combined in her with an elegant appearance and a sweet nature. For many years she has been a highly respected, well-loved teacher at the University of Southern California and at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, where she also accompanied the Lehmann master classes in lieder while Lotte was teaching there.

The following poignant reminiscence from Emmelin Stringham is worth sharing: “One day in 1955 when I was studying at the Music Academy of the West, I heard the most glorious music coming from the recital hall. Opening the door I crept in and took a back seat. There was a huge, high-backed chair in the center aisle and I could just see the white face of a lily protruding out across one arm. From the energy in the room I could sense that there was commanding presence seated in that chair, and of course it was the incomparable Lotte Lehmann. She was working with a young black woman who was singing a song that I was to learn was Schubert’s Gretchen am Spinnrade. At the piano was a lovely, gray-haired woman whose playing was exquisite, so in touch with the singer that their music seemed to be from one celestial source. That marvelous, interpretive coaching session by Madame Lehmann was to change my life. I was completely overwhelmed and as the tears rolled down my cheeks I knew my musical life was to be spent as a vocal accompanist. The singer that day was Grace Bumbry, and that extraordinary accompanist, the incomparable Gwendolyn Koldofsky!”

This seems to be an appropriate spot for the following article: From the Guardian of Sunday 4 March 2012 by Tom Service

Accompanists: the unsung heroes of music

They get little credit and less pay than the singers they support. So why do accompanists do it? Pity the poor accompanist, condemned to sit in the shadow of the great voices and the even greater egos of today’s singers. Being the pianist who plays for them can feel like the most thankless job in music. The singers couldn’t do it without them, but it’s the braying sopranos and the yodelling tenors who get all the glory, as well as most of the cash and applause – despite the fact that all they’ve done is sing a few tunes, usually in a foreign language, while the pianists slog their guts out playing fiendishly difficult accompaniments by Schubert, Schumann or Britten.

It’s a life that Roger Vignoles, the veteran British accompanist who has worked with everyone from Kiri Te Kanawa to Anne Sofie Von Otter, laments in his hilarious song The Battle Hymn of the Accompanist. “I only make believe I’m following their Lieder,” he sings. “That’s what I’m staying for/ That’s what I’m playing for/ Art is calling for – me!” And later: “You may think this job sucks/ When they get all the bucks/ Forget their lines, transpose/ And jump from page to page!”

After four decades at the top of his profession, however, Vignoles is finally getting to call the shots, having curated a series of eight concerts at the Wigmore Hall in London. Billed as a showcase of song that will celebrate the relationship between pianist and singer, the series features such sopranos as Joan Rodgers and Sandrine Piau. Vignoles will still be on the piano, of course, but for once it’s his baby, his name in lights. How would he sum up his craft? “I sometimes describe it as the art of getting what you want without the other person noticing.”

The archetypal British accompanist was Gerald Moore, who lamented his plight just as passionately as Vignoles, despite the fact that he was assisting the likes of Elizabeth Schwarzkopf. “We accompanists,” Moore said in his 1960s recording The Unashamed Accompanist, “have our minds above such mundane things as fees. But I would like people to realise what extremely important people we accompanists are. The most enchanting lady walks on to sing, and all the ladies look at her because of what she’s wearing, and all the men look at her because – well, all the men look at her. And nobody looks at me. And I can’t blame them. Nobody notices the accompanist at all. He looks so slender and shy and so modest that people think he’s there just to do what he’s told, to follow the singer through thick and thin. Well, there’s a great deal more to it than that.”

You would have thought that, by now, musical culture would have twigged that there’s more to a song recital than the singer. But is anyone really listening to what these toiling accompanists are doing? As pianist Anna Tilbrook – who plays for, among others, tenor James Gilchrist – puts it: “These songs would sound pretty strange without the piano.”

Iain Burnside, another seasoned accompanist, agrees. “I always think of what my mentor, Eric Sams, said – that the whole song repertoire is a piano art form rather than a singer’s. After all, the great Lieder and song composers were pianists.” This is a good point: think of Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Wolf, Fauré and Debussy. “Hardly any of them sang,” says Burnside. “Once you’ve got that idea in your brain, it’s hard to be comfortable with the idea that what you’re doing is merely ‘accompanying’.” And in Lieder, of course, it’s the pianist who leads.

“I hate the term accompanist,” continues Burnside. “You can’t deny there are connotations that it’s a secondary entity. But unfortunately I can’t think of a better one. If you insist on being called a pianist then people think that you’re comparing yourself to Sviatoslav Richter. That’s not what it’s about: you’re just asking to be taken seriously in your own right.”

It’s not just in the fees that Burnside sees inequality, but in the promotion, the fact that the singer – or instrumental soloist – has their name in lights, while the pianist’s name appears as an afterthought on the CD cover, poster or review. “When a ‘proper’ pianist like András Schiff or Mitsuko Uchida plays for a singer, they will get half the review, whereas when I’m playing the same repertoire – or Roger, or any of us – we’ll get one adjective, usually ‘sensitive’, and that’s it.” The irony is that the colour, range and collaborative alchemy that a skilled accompanist will deliver is precisely what a professional soloist, be it Schiff or Uchida, would struggle to create.

Tilbrook knows what it’s like to be regarded as the backdrop. “There are singers you build up a rapport with,” she says. “But you also get a soprano who says you’ve got to wear a more understated dress than hers so you don’t upstage her. Maybe that’s why there are hardly any female accompanists.”

While Vignoles embraces life as an accompanist, he is determined for it to be seen as an art form in its own right. That means celebrating the things accompanists can do that no other musicians can. He talks of the piano as a reservoir of colour that needs to create the infinite emotional variety required in everything from Schubert to Debussy, Dvo?ák to Copland. But it’s more subtle even than that. “Every voice you play for requires a different background,” he says. “Every person you work with is giving you something different all the time. My playing has become much more interesting because of that, because of all the people I’ve had to work my playing against. The most exciting thing is when something new happens in a concert, when you say to each other afterwards, ‘We’ve never done it like that before, but it was right for that moment.'”

More than anything else, what unifies these accompanists, in their passionate but egoless profession, is the thrill of doing justice to magnificent music. “There’s no getting away from the fact that the greatest songs ever written are in a foreign language,” says Vignoles. “But what they are all really about is universal human experiences. That’s the most important thing we do: project natural human feelings in a way that transcends time and place.”

Vignoles talks of a virtual telepathy, moments when he knows what the singer is going to do before they do, invisible connections that bind his fingers and their voice. As Burnside says, “You build up a kind of musical radar. You become attuned to a singer’s breathing, you get a sense of what their breath span is, and when they’re likely to be heading for trouble. It’s quite a private, sensual thing, listening to someone’s breath that intently.”

Tilbrook says there are times when she has saved singers from embarrassment. “The real art is to have that sixth sense, knowing when they are going to have a memory lapse, when they’re going to come in a bar early or even skip a whole verse. You have to be able to cover all that in your playing, so smoothly that no one notices.”

Doesn’t that mean Tilbrook is allowing these singers to get away with murder – and getting none of the credit for her skilled coverups? “Yes! But I love to be able to do that. It’s great when you think no one would have known there was a mistake. You have to be totally on your mettle, totally in the moment – and totally aware of the person you’re accompanying.”